Introduction

Most adults in the United States drink alcohol and drive motor vehicles. Despite the attendant risks, the two behaviors are often combined, which increases the likelihood of traffic crashes. Based on responses from 6,999 U.S. licensed drivers in a 2008 nationally representative telephone survey, it was estimated that 85.5 million drinking driving trips (in which an individual drove a motor vehicle within 2 hours of drinking alcohol) were taken by Americans in the 30 days prior to the survey (Drew, Royal, Moulton, Peterson, & Haddix, 2010). Estimates from the same National Survey of Drinking and Driving conducted in 2001 indicated that nearly 94 million trips annually (or 11% of all drinking-driving trips) in the United States are made by alcohol-impaired drivers with blood alcohol concentrations (equal to or higher than the illegal limit of .08 grams per deciliter (The Gallup Organization, 2003). Finally, a nationwide roadside survey of nighttime weekend drivers indicated that 2% of randomly selected U.S. drivers had illegal BACs (Lacey et al., 2009). Alcohol-impaired driving crashes resulted in 9,878 fatalities in 2011, accounting for 31% of traffic fatalities in the United States that year (NCSA, 2012). Alcohol-impaired driving crashes injure an additional 200,000 Americans and cost $130 billion in societal costs in the United States annually (Zaloshnja & Miller, 2009).

Each year for the past decade, an estimated 1.4 million drivers were arrested for driving while impaired or driving under the influence (FBI, 2008). This number reflects only those apprehended by the police. However, research indicates that detection and apprehension of impaired drivers is rare, with less than 1 arrest for every 300 trips by drivers with illegal BACs (.10 g/dL at the time of the study; Beitel, Sharp, & Glauz, 2000; Hause, Voas, & Chavez, 1982).

DWI recidivism remains a serious problem on our roadways across the Nation. About a third of the drivers arrested for DWI are repeat offenders (Fell, 1995). A driver is considered a repeat offender if the driver has been charged more than once with an alcohol-related offense (DUI, DWI, implied-consent refusal, test failure, administrative license action, or a zero-tolerance violation, etc.). DWI recidivists carry higher risk of future DWI arrests, as well as involvement in both alcohol-related and non-alcohol-related crashes (Gould & Gould, 1992; Perrine, Peck, & Fell, 1988), especially fatal crashes (Fell & Klein, 1994). They constitute anywhere from 20 to 47% of drivers arrested for DWI, depending upon the State examined (Fell & Klein, 1994). Drivers with prior DWI arrests are overrepresented in fatal crashes by a factor of 1.62, or are 62% more likely than those without prior DWI arrests to be in a fatal crash. Similarly, those with prior DWI arrests are more likely to be drinking drivers in fatal crashes by a factor of 2.38 among drivers with low BACs (.01 to .07) at the time of crashes to a factor of 3.81 among drivers with higher BACs (.08+) at the time of crashes (Fell, 2013). Given their greater involvement in fatal crashes and, particularly as drinking drivers in fatal crashes, repeat offenders cause a disproportionate amount of harm to society in terms of injuries and economic costs (Fell, 1992).

Intensive Supervision of DWI Offenders

As outlined in A Guide to Sentencing DWI Offenders (NHTSA & NIAAA, 2006), keys to reducing DWI recidivism are certain, consistent, and coordinated sentencing and compliance monitoring. In one study, trained counselors interviewed DWI recidivists about the reasons they continued to drink and drive even after a DWI conviction. The counselors also asked the recidivists what countermeasures had positive effects on their behavior. Many of these repeat offenders reported need for thorough alcohol use assessment, self-commitment to dealing with alcohol problems, personalized treatment and education plan, and continued contact with caring individuals, which included those in authority (such as judges), to reinforce lifestyle changes (Wiliszowski, Murphy, Jones, & Lacey, 1996). DWI courts also emphasize these principles (Fell, Tippetts, & Ciccel, 2010).

NHTSA has specified the following six factors as important when dealing with DWI offenders in attempts to facilitate reduction in recidivism (NHTSA & NIAAA, 2006):

1. Evaluate offenders for alcohol-related problems and recidivism risk.

2. Select appropriate sanctions and remedies for each offender.

3. Include provisions for appropriate alcohol use treatment in the sentencing order for offenders.

4. Monitor the offender’s compliance with sobriety, sanctions, and treatment.

5. Act swiftly to correct noncompliance.

6. Impose vehicle sanctions (e.g., vehicle immobilization, impoundment, and alcohol ignition interlock devices; Voas, 1999; Voas & DeYoung, 2002), when appropriate.

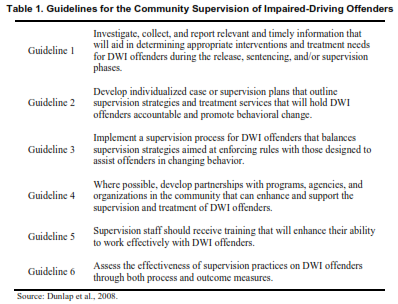

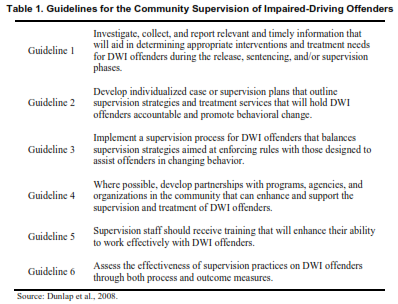

Factors 4 and 5—monitoring of offender compliance and swift action to correct noncompliance—also dovetail with the guidelines of the American Probation and Parole Association that probation services should follow to reinforce compliance of impaired-driving offenders under community supervision (Dunlap, Mullins, & Stein, 2008, Table 1; NHTSA, 2007). Most impaired-driving offenders are under some form of community supervision at some point during their sanctioning periods.

According to APPA, community supervision of DWI offenders should focus on public safety, offender accountability, and behavioral change. To accomplish this, States and communities have devised many variations of DWI offender supervision and probation programs with a variety of components.

Intensive supervision probation programs typically involve close supervision of offenders’ behavior through frequent contacts with a probation officer to monitor offender drinking and promote abstinence. A review of the literature indicates that the alcohol-monitoring strategies currently in use by ISP programs in both urban and rural areas are:

1. Unannounced visits by probation officers to the offender’s home to obtain breath tests and verify sobriety;

2. Randomized requirements to report for BAC testing where the offender must call in every day and determine whether on that day, he or she will need to report for testing;

3. Home confinement with scheduled or random BAC testing;

4. Transdermal alcohol-monitoring devices, such as ankle bracelets, that measure offenders’ BAC hourly;

5. An ignition interlock device to test the offender who, in addition to blowing into the unit whenever starting the vehicle, must also blow at times while operating the vehicle; and

6. Small portable photo-breath-test units that can require the offenders to provide several tests during the day to ensure abstinence.

Methods 1 to 3 have been used for some years and are widely applied throughout the country. Methods 4 to 6 are relatively new and have not been fully evaluated. Nevertheless, they are being widely tested by the States, and more than 18,000 TAM units are currently in use by the courts.

ISP programs for offenders convicted of DWI vary considerably around the United States. There are State “systems” that provide standard guidelines to counties and local communities within the State, and there are numerous local county and community programs that appear promising in reducing DWI recidivism. Wiliszowski, Fell, McKnight, and Tippetts (2010) prepared case studies for two State programs (Nebraska and Wisconsin), four individual area ISP programs (“Staggered Sentencing for Multiple DWI Convicted Offenders” in Minnesota; “Serious Offender Program” in Nevada; “DWI Enforcement Program” in New York; and “DUII Intensive Supervision Program” in Oregon) and two rural programs (“24/7 Sobriety Project” in South Dakota; “DUI Supervised Probation Program” in Wyoming). These ISP programs revealed certain common features:

-

Screening and assessment of offenders for their alcohol/substance abuse problem;

-

Close monitoring and supervision of the offenders, especially the monitoring of their sobriety;

-

Encouragement by officials to complete the program requirements successfully; and

-

Jail for noncompliance.

ISP programs provide convicted DWI offenders with support and individualized case supervision through ongoing contact with probation officers or case managers to help offenders deal with their substance use problems by connecting them with appropriate services (e.g., treatment, aftercare, employment). In ISP programs, alcohol monitoring is one component and is accomplished in various ways, including the breath testing of offenders twice a day. In contrast, stand-alone, twice-daily alcohol-monitoring programs modeled on the South Dakota 24/7 Sobriety Program are more circumscribed interventions for DWI offenders focused exclusively on substance use testing and, when necessary, sanctions. Such programs do not involve ongoing contact with a probation officer or case manager and close supervision of an offender’s life circumstances more generally as occurs in ISP programs. Rather, 24/7 sobriety programs are substance-use testing programs operated by law enforcement and applied to offenders both pre-and post-conviction to help ensure their compliance with court orders for bond or probation. Although judges also often order offenders to participate in activities such as treatment, victim impact panels, community service and so forth, such requirements are in addition to but not part of the 24/7 program.

24/7 Sobriety Programs

In their court orders, judges often require repeat-or high-BAC offenders to abstain from the use of alcohol as a condition of their probation or while they are awaiting their trials. However, in the past, no effective program existed to ensure compliance with sobriety. In the early 1980s, Larry Long, the prosecutor in Bennett County, South Dakota, hypothesized that if he could find a way to keep most of the alcohol offenders sober, it might be better and more cost-effective than sending them to jail. As an alternative to jail for repeat offenders, Long offered them a program in Bennett County where they came to the Sheriff’s Office twice a day for alcohol breath-testing. Upon becoming the South Dakota Attorney General, he convinced the South Dakota legislature to provide funding to pilot-test the program in four counties beginning in January 2005. The 24/7 program requires defendants arrested for a second or subsequent DUI offense to appear at the local sheriff’s office twice a day between 7 and 9 a.m. and 7 and 9 p.m. for breath tests. Those who fail to appear for testing or whose breath test shows consumption of alcohol have their bonds or probations revoked. As an alternative to the breath test, offenders instead can choose to wear TAM devices that use electrochemical sensing technology to test perspiration at the surface of the skin for the presence of alcohol. Drug patches and urinalysis testing also are sometimes used to monitor offenders’ other drug use status. The term 24/7 has been applied to programs modeled after the one in South Dakota that establish ongoing, twice-a-day alcohol monitoring of DWI offenders.

Following the lead of South Dakota, two States—North Dakota and, more recently, Montana— have passed legislation establishing statewide 24/7 sobriety programs. Sheriffs in each county decide whether to participate in the programs and the logistics of how the program will be operated (where testing will be conducted, the testing times, etc.). In these programs, offenders appear at the local sheriff’s office each morning and evening for breath testing. Among the key features of a 24/7 sobriety-monitoring program that make it of special interest are:

1. It makes use of existing police facilities and standard police equipment—handheld preliminary breath-test devices. No expensive computer or testing equipment is needed.

2. It is low cost ($1 to 2 per test; $2 to 4 per day) compared to $5 to 10 per day for TAM devices, and the cost is paid by the offender.

3. It may replace some or all of the jail time for multiple DWI offenders, thereby reducing jail costs.

4. It is applicable to all types of alcohol offenders, not just DWI offenders.

5. It can be imposed as a condition of bond so it can be applied close to the time of arrest rather than months later when the trial occurs.

Of particular interest is the significance of having an offender breath tested in the police station where, if the test is positive, the individual will be immediately jailed. In remote alcohol-monitoring systems, a warrant must be issued and served before an offender can be brought into court for sanctioning. Thus, the procedure involving testing at a centralized facility provides the best application of deterrence theory in that a significant penalty immediately follows the offense.

Evidence of Effectiveness of 24/7 Programs

Although 24/7 sobriety programs are relatively new and their use has been confined to rural communities, preliminary evidence from a few evaluations suggest that twice-daily alcohol monitoring holds promise for reducing DWI recidivism. An evaluation report by Loudenburg, Drube, and Leonardson (2010) examined the program’s effects on DUI first offenders and repeat offenders. The DUI recidivism rates after 3 years for 24/7 first offenders (with BACs > .17 upon arrest) was not different from those of similar offenders not on 24/7 (14.3% compared to 14.8%, respectively). However, there was a significant 74% reduction in recidivism after 3 years for DUI second offenders (3.6% versus 13.7% for comparison offenders), a 44% reduction in recidivism for DUI third offenders (8.6% versus 15.3% for comparison offenders), and a 31% reduction in recidivism for DUI fourth offenders (10.7% versus 15.5% for comparison offenders). Although assumed to be a contributing factor, no direct association between the 24/7 program and reductions in impaired-driving fatal crashes or crashes in general have been found to date. According to the 24/7 program coordinator, South Dakota’s campaign to reduce fatal crashes has included numerous approaches: increased DUI patrols, sobriety checkpoints, and an extensive DUI public education and information program, in addition to the 24/7 program.

In addition to the Loudenburg, Drube, and Leonardson study, the RAND Corporation recently conducted an independent evaluation of the South Dakota 24/7 program. According to Kilmer, Nicosia, Heaton, and Midgette (2012), there was a 12% reduction in repeat DUI arrests and a 9% reduction in domestic violence arrests associated with the adoption of the 24/7 program.

Feasibility of 24/7 Programs in Urban Locales

As noted previously, monitoring sobriety is often one component of ISP programs, but it also may be used as a stand-alone program to enforce court orders for sobriety. This latter model of a stand-alone, twice-daily alcohol-testing program is the focus of this report. The 24/7 concept developed in South Dakota and in use in several western States has gained popularity among prosecutors and judges and has shown initial promising results in terms of reducing DWI recidivism. Although much remains to be learned about the 24/7 program (e.g., whether it results in reduced jail time and lower rates of offender recidivism), the program model is being considered for implementation in additional States and communities. Currently, information about the program is confined to large western States that are overwhelming rural, frontier, or both. Thus, important questions remain unanswered about whether and how this program model could be applied in more densely populated locations such as urban areas.

The current study was undertaken to address the issue of whether the 24/7 concept can be scaled up to urban settings. The study was conducted in two phases. In Phase 1, extensive information was collected from existing 24/7 programs in rural States to gather current information on program activities, resources, costs, offender populations, outcomes, challenges and modifications, and guidance for urban officials in implementing a twice-daily alcohol-monitoring program. The results of Phase 1 were used to inform the next phase, the assessment of feasibility. In Phase 2, data were collected via discussions with local officials in two jurisdictions—Washington, DC, and Fairfax County, Virginia—to gather information on urban officials’ perceptions about the benefits, challenges, required changes, and expected outcomes of implementing a 24/7 program in urban areas.

The purpose of the feasibility study was to assess whether the 24/7 program model could be transferred to an urban location and, if so, what modifications and resources might be necessary to apply it to a more populous setting.