CHAPTER 53

THE BUSOGA LAND QUESTION (AQUIRING AND SETTLING ON LAND)

The Paramount chief in his area was the king of that area and had full powers, with the co-operation of his council, to use that land as he wished. For any other person to obtain and own land which he could use for his own purposes, the procedure was as follows: -

All types of people could possess land given to them by the king of the area. There were many ways through which one could obtain and own land. The princes could be given land just because they were princes, even if they had done nothing for the country. The size of such land was determined on the suggestion of either the prime minister or the chief wife or by the council of deputies and could be anything from a part of a mutala to even more than one mutala. Sometimes the mother of a prince, if she had good land at her parents’ home, could influence the king and his council to send the princes to her home area to rule his uncles.

The prince’s uncles in that case would send gifts to the king, the prime minister and deputies for favouring their relative in that way. The gifts could be cattle, goats, chickens, hoes, barkcloth, a girl or a slave, if possible. But if a prince was given an area other than his mother’s home area, a deputy would accompany him to the area and order the chiefs to keep the prince safe. The chiefs of that area would then send gifts to the king and his deputies to thank them for giving their area a prince.

Most princes used to be given land while they were still young. After being given land, that prince was removed from his father’s home and a separate home was built for him, even if he was still young. He would stay in that home until he grew up to marry wives and had to stay in that home permanently unless he was given a better place or unless he committed an offence, when he would be driven away from the village.

The prince had complete power over his land. He could sell land to other people who wished to settle on his land, and had power to chase away anybody whom he did not like or who committed a crime.

He used to appoint deputies to assist him in ruling his area and he determined what taxes to collect from his tenants. All the men could be summoned to work for him, if he wished, the main work being the building of his houses and cultivation of his banana gardens. The ruler of the village would reward his peasants for this work by providing a feast, including an ox and beer. The brave men on this occasion would stand up to swear and promise always to support the chief but if the chief or prince did not treat his people in this way, they were displeased with him and declared that he was not generous, and they would always work for him unwillingly.

The chief of a big village could sub-divide the village into smaller units, appointing a sub-chief for each unit. These sub-chiefs used to pay to the chief and his deputies in return. These sub-chiefs used to become hereditary landlords and could only be dismissed if they offended.

In addition, people of different categories could be given land and become permanent landlords. They included the following: - brave men favourites, maternal uncles of the chief, the chief’s in-laws, the chief’s nephews, sooth-sayers, the entertainers, the children of the chief’s deputies, people of the chief’s clan, people of the deputies’ clans, detectives, traders, princesses, grand-parents and any other people who deserved and due to their services to the king and his people. All the foregoing could be given land and become permanent land-owners who could only leave the land if they obtained alternative land and if they committed offences such as the following : - witchcraft, adultery, murder, disobedience, theft or conspiring with outsiders to commit murder.

Those are some of the crimes which would lead to the expulsion of one from his land, and such land could then be re-allocated at the wish of the council.

Alternatively an offender could forfeit part of his land in addition to a fine.

To obtain land one had to go through many channels. One had to begin by befriending the chief’s deputies, by giving them as many gifts as he could afford. The chief deputy would then introduce him to the ruler, showing also what gifts he had brought in order to apply for land. The nature and size of gift was not laid down by the authorities, it was up to the applicant to decide according to tradition.

After the chief deputy (or the Prime Minister) had made formal introduction of the applicant to the king, the applicant was shown the piece of land or was promised land when it later became available, the applicant thus returning to his home. He could return as soon as possible, bringing with him a gift to remind the prime minister and the chief of his request. The applicant could be sent back home telling him that the authorities were still looking around for land. This could be repeated many times, taking a full year or even longer, if the applicant was unlucky before one obtained land.

Sometimes an applicant was asked to bring a specified gift and he did so. More often than not an applicant had a definite piece of land in mind - it could be land near his home or land which once belonged to his father or to his clan. As it sometimes happened that the land applied for was still inhabited by an innocent person, the authorites would not find it easy to grant the applicant his request and had to wait until the occupant of the land requested was given alternative land. If this failed, then the applicant gained nothing from his gifts. Also, if it happened that the chief or his deputy were replaced before the applicant was granted the land, the gifts hitherto given to the authorities were a loss to him and he had to start afresh with the new rulers. If it happened that the applicant died before receiving the land, no account was taken of what he had paid so far and his heir had to start fresh negotiations.

The gifts most commonly offered for purchasing land were - cattle, goats, chickens, hoes, girls, slaves and bark cloth. Ivory could also be paid but the more important chiefs who could obtain more gifts from their big areas could send their messengers to Mount Elgon for the tusks. Anyone who could offer ivory willingly because of land would be considered quickly if there was no serious objection to his being given land immediately.

Ivory used to be given to the chief and not to his deputies; the latter were entitled to any other gifts except ivory.

To be made a landlord, one had to be permitted by the Paramount chief (Kyabazinga-King) and his deputies after paying whatever was required of him by the authorities. The Katikiro (Prime Minister) and another deputy used to send a representative each to take the new landlord to his new land.

The two representatives would then gather all the men of the village and introduce to them the new landlord. The new landlord was again required to pay certain goods to the representatives as the latter decided. Failing to do so, the representatives would withhold the land from him until he had paid them fully.

The new landlord used to find these goods easily once he was introduced to his land. For he would immediately levy a tax from all his tenants

(known as ‘Engalula-Mulyango). This tax was paid by all loyal tenants and anyone who would not pay it would be declared a rebel and would be evicted immediately. In this way the new landlord could easily pay the representatives their due and make up for any other goods paid originally for the land.

The rite connected with newly acquired land or banana gardens insisted that the man on the first night would sleep with his oldest wife (the ‘Kadulubaale’). If he failed to do so and slept with a wife other than the kadulubaale, he was believed to have ruined all his future prosperity. Bananas and even banana leaves could not be taken from the new land or garden before this rite had been fulfilled. The oldest wife had to take the first bunch and the first bundle of leaves from the new banana garden. On receiving a mutala, a kisoko or one or more banana gardens, the new landlord, after saying farewell to the introducing representatives and after being shown all the boundaries, would let the representatives depart.

He then became the hereditary landlord and the land could then be held in succession by his children and grandchildren unless they were evicted after committing crimes.

Small banana gardens used to be given to sub-tenants by the big landlords. But the ruler himself had power over special banana gardens which he could offer to landlords according to the tradition governing land.

The Kyabazinga (King) would reserve for himself special mitala which he could not give to other people. The mitala were hereditary and were occupied by whoever inherited the chieftainship. On these mitala headquarters were built and the Chiefs were buried. But the ruler could build a home on any other land in his country, offering alternative land to the owner of that land.

On the chief’s mitala, the chief, himself had the power to appoint minor chiefs to look after his land. He would appoint them from amongst his deputies, his slaves, his maternal uncles, or from any other people.

The only exception was the princes, because if these were appointed, they would claim the mitala and become landlords. It used to be permissible for other people to settle pemanently on the chief’s mitalla, as is the custom to-day.

It used to be impossible for a poor man to become a landlord because one was required to pay very heavily the authorities. If one paid a few things, one would only get a small piece of land in return.

But a man who was not well to do could also obtain land from any landlord on payment of a few things such as goats, hoes, bark cloth or chickens. On payment of the foregoing or any one of them, a tenant could be given land by a landlord to thank him for the land or banana garden.

On the death of an important landlord, a deputy or prince, a prominent person in the area or one of his deputies would report the news to the King. The report was accompanied with some of the property of the deceased such as one or two hoes, a goat or a cow, or barkcloth, depending on the wealth of the deceased. These were offered to the King to accompany the news of the death of a chief, prince or deputy.

The King and the Prime Minister would then send their representatives to the funeral. The king would also send one cow and barkcloth to the funeral and these would be handed to the master of ceremonies at the funeral. The representatives also took the name of the heir to the funeral, as the choice of the heir was made by the king and not by the clan. That is why every chief used to send one son to serve the king, at the death of the chief, his son automatically became the heir.

A chief could not be buried until the king’s representatives had arrived with the king’s gift and had named a heir.

After the funeral the heir would give to the king’s representatives cattle, goats and barkcloth, according to his ability, to take to the king and the prime minister, and a share to themselves.

No chief could be buried without the authority of the king. If it were found out, the head of the funeral ceremonies would be punished by removing his property and the heir would be expelled. This custom used to be also observed in Bunyoro. The Omukama used to send a heir with a spear to kill the cow to celebrate the death of the chief, together with a shield to please the chief god, Mukama.

A man, on obtaining land, could not live on that land before the rite of sleeping with his oldest wife had been fulfilled.

A landlord had the power to evict a tenant or to reduce his piece of land even if the tenant had paid fully for it. Useful trees growing on a tenant’s land could only be cut down with the permssion of the landlord. Such trees included muvule, musita and other useful species. If a tenant wanted to make use of one of those trees, he would pay for it or would do some work for the landlord in payment for it.

A tenant could bury members of his family on his land without the permission of the landlord; but to bury a visitor on the land one had to pay a special tax. That was the rule until the coming of Europeans. This tax was proportional to the wealth of the tenant.

If the tenant was wealthy, he would pay cattle, goats, or hoes and one of these things would be sent to the Kyabazinga, some were taken by the landlord and the remaining few to the chiefs’ deputies. After paying this tax, the dead visitor was then buried. This rule applied to all visitors including natives of the country as long as they were visitors to the village. Transport of dead bodies was not permitted except in the case of prominent people. Peasants’ corpses were only moved at night.

If it was found that a tenant had buried the corpse of a visitor without informing the local chief, the tenant’s entire property would be confiscated and sometimes he would also be evicted. A tenant was not allowed to bury the corpse of a visitor before paying the tax. If he failed to pay the tax, he was ordered to throw the corpse into a forest, in a river or in the lake if there was one nearby.

A man offered land would please himself where to build his house and would cultivate it as he pleased provided he did not exceed the boundaries. His children and dependants were free to build houses on the land and to cultivate it as they wished if the land was sufficient and to grow any crops except those which were considered to be connected with witchcraft. The tenant was also free to grow any trees on the land without permission from the landlord. There was no taxation on crops; but if any other man was lent land by a tenant, on harvesting the crops the man had to give a portion of the harvest to the landlord.

Livestock used to be grazed wherever there was suitable grass; but mainly they used to graze in swamps, as the rest of the land was taken up with banana gardens and other food crops.

Except in the case of very prominent and respectable people no ordinary man, even if he was a landlord, could receive a visitor from another part of Busoga outside the jurisdiction of the host’s home area. If anyone was found with an outside visitor, he faced a very serious charge. All his property would be confiscated, his children and his wives were taken away as slaves and he would be evicted from the land. This was done because visitors were always suspected of spying on the chiefs with the intention of murdering them later. Therefore every village was very suspicious of outsiders.

There were no permanently established taxes known by the people, but every chief, at his discretion, used to order his prime minister to ask his minor chiefs to send round tax collectors. These collectors could not go directly to the peasants but went to the chiefs of villages or the princes and told them what he required. The collector would stay at the home of the local chief and the chief would then send round his collectors to bring in the tax as required. The collectors then brought whatever they collected to the chief and sent the rest to the Katikiro. The latter also took his due share and then sent the rest of the things to the king.

Tax collected in this way was never sufficient for this reason : most chiefs collected their own shares without waiting for the king’s orders. Besides taxes, the chiefs and the king received things in many other ways; they received many gifts from peasants, such as cattle, goats, chickens, bark cloth, hoes and many other things. The forfeiture of other people’s property was another way in which chiefs obtained their wealth. By custom, any person who brewed beer gave part of it to his chief; if he failed to do this, his property would be forfeited.

The peasants of any given area worked for their chief, such as building houses for him, or weeding in his shambas. This service was given whenever desired. Anybody who refused to give this service was liable to severe punishment.

There were public markets in certain villages; the chief in whose country the market was appointed a market-master who collected daily rent. The largest part of the rent was sent to the king; the other small part was shared between the chief and the market-master, The rent was paid for these things: - bark cloth, chickens,bunches of matoke, dried banana, fishpots, knives, baskets, water pots and wood-work of many types. Each trader of these things gave away one or two of the same things as rent.

A tax of some kind was also imposed on hunters; if they killed any animal, the owner of the mutala in which the animal was killed was entitled to a portion of the meat; but if the hunter refused to pay this tax, they would be arrested and sued at court and fined. In case the animal killed was a big one, the portion claimed by the chief, or the king in certain cases, amounted to a piece of one leg of the animal.

Anything picked up on the way was reported to the chief who was responsible for finding the owner, or sending it to the ruler, in case the owner could not be found. There were piers in certain places on the lake where people who had boats (canoes) operated a transport service. Even here there were collectors responsible for collecting rent. This rent was shared between chiefs in the same way as the market rent was shared. Fishermen, carpenters, blacksmiths and other traders were taxed according to their trade.

In case of wars, every man was expected to offer his services. Whenever a war broke out, men were collected from every part of the country to go and fight. There was a drum sounded to summon everybody whenever danger was imminent. This drum was named “Mukidi” and was widely known for its alarming nature. If any man failed to respond, at the sound of this drum, he was in danger of losing his property or even being sent into exile. or punished in many other ways, he was looked down upon by his fellow men who refused to have any dealings with him, and his wives were equally scorned by other women; the man and his wives automatically lost every right in the country.

In Busoga there were no well-established land systems, such as freehold, or mailo system, just as it is in Buganda. People respected and maintained the old system of acquiring land as stated above. The presence of mitala and bisoko is a testimony to that system. In 1892, after the arrival of the British, the Protectorate Government encouraged mailo system in Busoga. The chiefs in power then were asked by the Government to acquire mailo land surveyed and registered. The mailo system was much better than the one in operation then.

Before complying with the request, the chiefs required the Government to tell them what would happen to the rest of the land and the Government stated that such land would become Government property. On learning this shocking truth, the chiefs refused to take the advice, and the mailo system was completely forgotten in Busoga until 1902 when the matter was brought up again by those chiefs who realised the usefulness of mailo system. These chiefs then requested the Government to introduce the mailo system once again in Busoga, just as it was in Buganda. Colonel James Henyes Sadler, then Governor of Uganda, accepted the request and promised to work it out immediately. But the promise was never fulfilled until late in 1902 and as a result of many reminences in the said years, the Government promised afresh and in 1912, Mr. Grant, Acting Provincial Commissioner, wrote a letter to the Chief Secretary at Entebbe, submitting to him the plan of the mailo system in Busoga. This letter was No. 16/11/ of 17 April, 1912. A commission was then sent from Entebbe to Busoga to discuss and plan out the mailo system in Busoga; the same commission was also sent to Ankole, Bunyoro and Tooro. The commission was headed by Chief Justice Tom Morris Carter. The commission allotted 505 square miles to the chiefs and 408 square miles to ordinary people. The chiefs, including the President of Busoga Lukiiko, were 224 altogether. Of these, 8 were Ssaza Chiefs. The commission prepared a report for the Government, which was signed by Morris Carter on 15 March, 1913.

Following this date, there was much talk in the Government circles concerning the granting of mailo system in Busoga. Nothing practical resulted from this talk; the people of Busoga kept on reminding the Government and the latter continually promised. At one time the Government announced that the people of Busoga had been given a total of 613 square miles, that these miles would be surveyed and confirmed as soon as surveyors were available. One Ssaza chief, Yosiya Nadiope, wrote a letter to the P.C. Eastern Province, who was Mr. F. Spire, thanking the Government for its decision to allow mailo system in Busoga. He also complained in the same letter that the 3 square miles allotted to him officially, plus square miles of his own were nothing compared with the big size of the country that he ruled, and that chieftainship in his country was hereditary and equivalent to Kingship; he was, therefore, entitled to a much bigger share of the land.

Owing to the outbreak of World War I, the establishment of mailo land in Busoga was brought to a standstill until 1919; but the Basoga kept on harping on it to the Government. On receipt of every reminder, the Government stated emphatically that the total area which was promised would be surveyed and shared out among people. But in 1926 the Government departed from its promise and created a new term known as Crown Land; the Government stated that all Land in Busoga was Crown Land. This shocked every Musoga in all walks of life but there was no rising against the Government; the people were still hopeful. In 1930 the Government again promised just 85 square miles to those chiefs who had been found independent by the British. This area was to be located on unpeopled parts of the country. The idea of reviving the promise of mailo land in Busoga was welcomed but the total number of those who were entitled to the 85 square miles was 2,000 or more, so that it was impossible for them to share the 85 square miles. Furthermore, the Basoga found it very difficult to depart from the custom of living on their hereditary bibanja. No possible solution could be arrived at for a period of five long years. The people of Busoga continued to beseech, the Government to increase the number of miles to 613 but the Government refused. Many letters were written to the Government and the Secretary for the Colonies, Downing Street, London. This letter explained the Basoga’s complaints concerning the 85 square miles hereditary land, tax and hereditary chieftainship which was abolished in 1927, the year when salaries for chiefs were introduced and established. Another letter, which almost narrated the whole history of Busoga was written and sent through a legal adviser.

YOUNG BUSOGA ASSOCIATION (YBA) 1920

In 1920, a movement called the Young Busoga Association (YBA) was started by Y.K. Lubogo, this new association was founded purposely to promote the understanding and unity of the people of Busoga. In 1923 it turnedout to be a very successfully lobbying body which helped to advocate for the rights of workers in Jinja.

From 1929 to 1930 the association opposed all cotton buyers in Uganda who had formed a syndicate with the intention of cheating the growers. The association strongly advised all cotton growers in Busoga to boycott selling cotton to the syndicate. Because the association worked day and night travelling all over Busoga, the boycott was effective. Despite the Government’s threats, all cotton in Busoga was transported and sold at Tororo to a company known as L. Beson, which was not a member of the syndicate. As a result of the boycott, the syndicate collapsed and the cotton buyers signed an agreement with Y.B.A. to the effect that the syndicate would never be revived. After the signing of this agreement, the boycott was called to an end.

This matter greatly pleased all the Basoga because it gave them the advantage of stopping the people selling cotton outside the syndicate, it compelled them to raise the amount of money and therefore the cotton growers received much more money than they would have with the other sydicate. Also, the Y.B.A, did many other good things to help the tribes, not merely enriching themselves. It was majory a voluntary group and as such they never received any returns.

THE BATAKA MOVEMENT 1936

The question of land soon became serious in Busoga. Once the people were convinced that the Government was merely robbing them of their land, they founded a political body known as ‘Bataka of Busoga’ with the purpose of contending for their land. This movement was begun in 1936 and was led by a young man named Azalia Nviri, also known as Wycliffe in England where he was studying for five years. He returned to Busoga in 1929. The Bataka body was first limited to mitala and bisoko chiefs only, for these had a grievance against the Government which had stopped them from collecting the customary rent of shs 4 from their tenants. Instead of working for the chief, the tenants were paying a rent of shs 4. The Government had also decided to pay these chiefs, who disliked the idea and were determined to fight against it. They sincerely believed that acceptance of salaries would mean acceptance of defeat.

In 1908, Semei Kakungulu, who was President of Busoga, had advised that the various chiefs in Busoga should be allowed to choose areas of land to which they should be given titles. Any land which might remain over should revert to the Lukiiko and be termed gombololas, for which the Lukiko would be responsible to appoint chiefs or dismiss them as the case might be. The Proteotorate Government accepted this recommendation.

The landlords were to be given all power over their land, to appoint or dismiss sub-chiefs as they wished and to collect rent (‘busulu’). This is the system of mitala and bisoko chiefs which was in operation until 1927. In that year the Protectorate Government considered paying all Government servants, including those chiefs who used to collect rent from the peasants. All hereditary chieftainships were abolished.

All hereditary gombolola chiefs strongly opposed the abolition because they were adhering to all land within their gombololas until the Government could agree to the establishment of mailo land in Busoga. But the Government forcibly abolished all hereditary gombolola chieftainship. All hereditary gombolola chiefs were allotted salaries, including shs 4 or 12 days’ service by the peasants. This was to replace the rent of shs 10 or 30 days’ paid by the peasants, to which the chief was entitled by right.

Later on the Bataka Movement became widely political and concerned itself with many political aspects in Busoga. The Movement directed its attacks on the native rulers particularly. The Bataka considered that the whole or any particular one of the native chiefs was quite useless to the country. The Government, however, did not take at once what complaints the Bataka raised against the native chiefs. Soon the Movement broke down following the separation of certain members from the main body.

The separation was due to the fact that the Movement had lost sight of its original aim and was attacking irrelevant things. This movement was, never-the-less, very useful to Busoga in many ways.

Owing to this movement, the Government was kept informed of the feelings of the people. The same movement provided an opportunity for people from different parts of the country to meet together and exchange or share ideas. It thus helped to develop young men’ s mental capacities and, although it is still in its infancy

BRITISH ROYAL VISITS AND THE BUSOGA LAND QUESTION

The visit of the Princes of the British Royal Family was one of the most Important events in Busoga, such as the visit of the Duke of York to Uganda in 1927. The Prince of Wales also visited Uganda in 1928. Both of them visited Busoga. The visit of the Colonial Secretary to Uganda during 1934 also greatly pleased the Basoga, when he visited the Busoga District Council at Bugembe, Jinja on 18 January, l934.

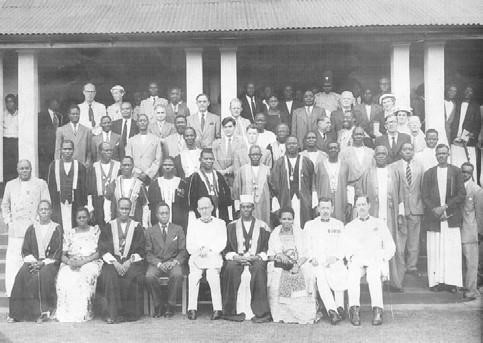

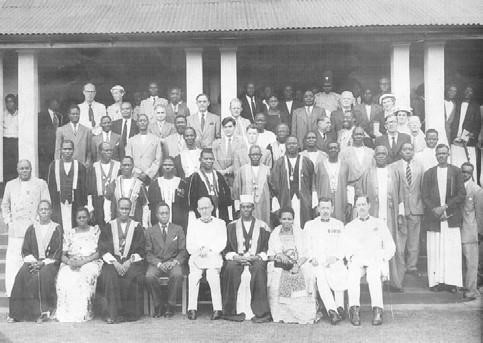

HRH, the Isebantu, hosting HRH the Kabaka of Buganda Sir. Edward Mutesa II (Seated fourth from left), Busoga Royalty and Colonial Administrators infront of the Lukiiko at Bugembe. - 1956

The Hon. E. Wako, President of the Busoga Council, spoke as follows before a large gathering of Basoga and other Africans, Europeans and Asians; “Sir, We, the under-signed chiefs in the District of Busoga, Eastern Province, Uganda Protectorate, on our part and on behalf of our people of Busoga, humbly beg to bring to you the following complaint for your kind consideration. Our complaints are all based on land problems in this District of Busoga.

To state the case briefly, the nature of the land problems in Busoga is as follows;

1. When His Majesty’s Protectorate of Uganda was first founded, there was no agreement made between His Majesty’s Government and the chiefs of Busoga concerning land in this country, nor was there any definite arrangement made. His Majesty’s or the Protectorate Government has never cared to make such an arrangement in order to meet the peoples’ complaints. This is where lies all the difference between ourselves and our neighbours, the Baganda, in whose country land has been granted to the Kabaka and his lineage, and to the various chiefs and other people, according to the 1900 Agreement.

2. Since time immemorial, as long as common law has been in operation, there has never been land disputes of discontent in Busoga. This state of affairs prevailed even during the immediate period after the foundation of the Protectorate of Uganda. But since this period there have been gross alterations amounting to some people being evicted from their land as stated below. Since that period, our authority in this country has become dangerous to us and a source of worries, mainly because the Government is gaining its own ends, leaving us the losers.

3. We have presented this complaint many times to the Protectorate Government and each time this Government has emphatically promised to grant us only 85 square miles which we have found very difficult to accept, as we shall elaborate on later. On the other hand, this Government agreed to sell large tracts of land to Europeans and Indians in Busoga. Furthermore, natives of Buganda are granted land in this country of Busoga an act which had long been forbidden.

We sincerely believe that an immediate consideration of the complaint concerning our land,