In Search of Primate Continuity

Two elements women share with bonobos are that their ovulation is hidden from immediate detection and that they have sex throughout their cycle. But here the similarities end. Where are our genital swellings, and where is the sex at the drop of a hat?

FRANS DE WAAL12

Sex was an expression of friendship: in Africa it was like holding hands…. It was friendly and fun. There was no coercion. It was offered willingly.

PAUL THEROUX13

Whatever one concludes about chimp violence and its relevance to human nature, our other closest primate cousin, the bonobo, offers a fascinating counter-model. Just as the chimpanzee seems to embody the Hobbesian vision of human origins, the bonobo reflects the Rousseauian view. Although best known today as the proponent of the Noble Savage, Rousseau’s autobiography details a fascination with sexuality that suggests that he would have considered bonobos kindred souls had he known of them. De Waal sums up the difference between these two apes’ behavior by saying that “the chimpanzee resolves sexual issues with power; the bonobo resolves power issues with sex.”

Though bonobos surpass even chimps in the frequency of their sexual behavior, females of both species engage in multiple mating sessions in quick succession with different males. Among chimpanzees, ovulating females mate, on average, from six to eight times per day, and they are often eager to respond to the mating invitations of any and all males in the group. Describing the behavior of female chimps she monitored, primatologist Anne Pusey notes, “Each, after mating within her natal community, visited the other community while sexually receptive … They eagerly approached and mated with males from the new community.”14

This extra-group sexual behavior is common among chimpanzees, suggesting that intergroup relations are not as violent as some claim. For example, a recent study of DNA samples taken from hair follicles collected from chimpanzee nests at the Taï study area in Ivory Coast showed that more than half the young (seven of thirteen) had been fathered by males from outside the female’s home group. Were these chimps living in a perpetual war zone, it’s unlikely these females would have been free to slip away easily enough to account for over half their pregnancies. Ovulating female chimps (despite the heightened male monitoring predicted by the standard model) eluded their male protectors/captors long enough to wander over to the other groups, mate with unfamiliar males, and then saunter back to their home group. This sort of behavior is unlikely in a state of perpetual high alert.

Whatever the truth regarding relations between unprovisioned groups of chimpanzees in the wild, unconscious bias rings out in passages like this one: “In war as in romance, bonobos and chimpanzees appear to be strikingly different. When two bonobo communities meet at a range boundary at Wamba … not only is there no lethal aggression as sometimes occurs in chimps, there may be socializing and even sex between females and the enemy community’s males.”15

Enemy? When two groups of intelligent primates get together to socialize and have sex with each other, who would think of these groups as enemies or such a meeting as war? Note the similar assumptions in this account: “Chimpanzees give a special call that alerts others at a distance to the presence of food. As such, this is food sharing of sorts, but it need not be interpreted as charitable. A caller faced with more than enough food will lose nothing by sharing it and may benefit later when another chimpanzee reciprocates [emphasis added].”16

Perhaps this seemingly cooperative behavior “need not be interpreted as charitable,” but what’s the unspoken problem with such an interpretation? Why should we seek to explain away what looks like generosity among nonhuman primates, or other animals in general? Is generosity a uniquely human quality? Passages like these make one wonder why, as Gould asked, scientists are loath to see primate continuity in our positive impulses even as many clearly yearn to locate the roots of our aggression deep in primate past.

Just imagine that we had never heard of chimpanzees or baboons and had known bonobos first. We would at present most likely believe that early hominids lived in female-centered societies, in which sex served important social functions and in which warfare was rare or absent.

FRANS DE WAAL17

Because they live only in a remote area of dense jungle in a politically volatile country (Democratic Republic of Congo, formerly Zaire), bonobos were one of the last mammals to be studied in their natural habitat. Although their anatomical differences from common chimps were noted as long ago as 1929, until bonobos’ radically different behavior became apparent, they were considered a subgroup of chimpanzee—often called “pygmy chimps.”

For bonobos, female status is more important than male hierarchy, but even female rank is flexible and not binding. Bonobos have no formalized rituals of dominance and submission like the status displays common to chimps, gorillas, and other primates. Although status is not completely absent, primatologist Takayoshi Kano, who has collected the most detailed information on bonobo behavior in the wild, prefers to use the term “influential” rather than “high-ranking” when describing female bonobos. He believes that females are respected out of affection, rather than because of rank. Indeed, Frans de Waal wonders whether it’s appropriate to discuss hierarchy at all among bonobos, noting, “If there is a female rank order, it is largely based on seniority rather than physical intimidation: older females are generally of higher status than younger ones.”18

Those looking for evidence of matriarchy in human societies might ponder the fact that among bonobos, female “dominance” doesn’t result in the sort of male submission one might expect if it were simply an inversion of the male power structures found among chimps and baboons. The female bonobos use their power differently than male primates. Despite their submissive social role, male bonobos appear to be much better off than male chimps or baboons. As we’ll see in later discussions of female-dominated societies, human males also tend to fare pretty well when the women are in charge. While Sapolsky chose to study baboons because of the chronically high stress levels males suffer as a result of their unending struggles for power, de Waal notes that bonobos confront a different sort of existence, saying, “in view of their frequent sexual activity and low aggression, I find it hard to imagine that males of the species have a particularly stressful time.”19

Crucially, humans and bonobos, but not chimps, appear to share a specific anatomical predilection for peaceful coexistence. Both species have what’s called a repetitive microsatellite (at gene AVPR1A) important to the release of oxytocin. Sometimes called “nature’s ecstasy,” oxytocin is important in pro-social feelings like compassion, trust, generosity, love, and yes, eroticism. As anthropologist and author Eric Michael Johnson explains, “It is far more parsimonious that chimpanzees lost this repetitive microsatellite than for both humans and bonobos to independently develop the same mutation.”20

But there is intense resistance to the notion that relatively low levels of stress and a surfeit of sexual freedom could have characterized the human past. Helen Fisher acknowledges these aspects of bonobo life as well as their many correlates in human behavior, and even makes a sly reference to Morgan’s primal horde:

These creatures travel in mixed groups of males, females, and young…. Individuals come and go between groups, depending on the food supply, connecting a cohesive community of several dozen animals. Here is a primal horde…. Sex is almost a daily pastime…. Females copulate during most of their menstrual cycles—a pattern of coitus more similar to women’s than any other creature’s…. Bonobos engage in sex to ease tension, to stimulate sharing during meals, to reduce stress while traveling, and to reaffirm friendships during anxious reunions. “Make love, not war” is clearly a bonobo scheme.21

Fisher then asks the obvious question, “Did our ancestors do the same?” She seems to be preparing us for an affirmative answer by noting that bonobos “display many of the sexual habits people exhibit on the streets, in the bars and restaurants, and behind apartment doors in New York, Paris, Moscow, and Hong Kong.” “Prior to coitus,” she writes, “bonobos often stare deeply into each other’s eyes.” And Fisher assures her readers that, like human beings, bonobos “walk arm in arm, kiss each other’s hands and feet, and embrace with long, deep, tongue-intruding French kisses.”22

It seems that Fisher, who shares our doubts about other aspects of the standard narrative, is about to reconfigure her arguments concerning the advent of long-term pair bonding and other aspects of human prehistory to better reflect these behaviors shared by bonobos and humans. Given the prominent role of chimpanzee behavior in supporting the standard narrative, how can we not include the equally relevant bonobo data in our conjectures concerning human prehistory? Remember, we are genetically equidistant from chimps and bonobos. And as Fisher notes, human sexual behavior has more in common with bonobos’ than with that of any other creature on Earth.

But Fisher balks at acknowledging that the human sexual past could have been like the bonobo present, explaining her last-minute 180-degree turnaround by saying, “Bonobos have sex lives quite different from those of other apes.” But this isn’t true because humans—whose sexual behavior is so similar to that of bonobos, according to Fisher herself—are apes. She continues, “Bonobo heterosexual activities also occur throughout most of the menstrual cycle. And female bonobos resume sexual behavior within a year of parturition.” Both these otherwise unique qualities of bonobo sexuality are shared by only one other primate species: Homo sapiens. But still, Fisher concludes, “Because pygmy chimps [bonobos] exhibit these extremes of primate sexuality and because biochemical data suggest [they] emerged as recently as two million years ago, I do not feel they make a suitable model for life as it was among hominids twenty million years ago [emphasis added].”23

This passage is bizarre on several levels. After writing at length about how strikingly similar bonobo sexual behavior is to that of human beings, Fisher executes a double backflip to conclude that they don’t make a suitable model for our ancestors. To make matters even more confusing, she shifts the whole discussion to twenty million years ago as if she’d been talking about the last common ancestor of all apes as opposed to that shared by chimps, bonobos, and humans, who diverged from a common ancestor only five million years ago. In fact, Fisher wasn’t talking about such distant ancestors. The Anatomy of Love, the book from which we’ve been quoting, is a beautifully written popularization of her groundbreaking academic work on the “evolution of serial pair-bonding” in humans (not all apes) within the past few million years. Furthermore, note how Fisher refers to the very qualities bonobos share with humans as “extremes of primate sexuality.”

Further hints of neo-Victorianism appear in Fisher’s description of the transition our ancestors made from the treetops to life on land: “Perhaps our primitive female ancestors living in the trees pursued sex with a variety of males to keep friends. Then, when our forbears were driven onto the grasslands of Africa some four million years ago and pair bonding evolved to raise the young, females turned from open promiscuity to clandestine copulations, reaping the benefits of resources and better or more varied genes as well.”24 Fisher assumes the advent of pair bonding four million years ago despite the absence of any supporting evidence. Continuing this circular reasoning, she writes:

Because bonobos appear to be the smartest of the apes, because they have many physical traits quite similar to people’s, and because these chimps copulate with flair and frequency, some anthropologists conjecture that bonobos are much like the African hominoid prototype, our last common tree-dwelling ancestor. Maybe pygmy chimps are living relics of our past. But they certainly manifest some fundamental differences in their sexual behavior. For one thing, bonobos do not form long-term pair-bonds the way humans do. Nor do they raise their young as husband and wife. Males do care for infant siblings, but monogamy is no life for them. Promiscuity is their fare.25

Here we have crystalline expression of the Flintstonizing that can distort the thinking of even the most informed theorists on the origins of human sexual behavior. We’re confident Dr. Fisher will find that what she calls “fundamental differences”

in sexual behavior are not differences at all when she looks at the full breadth of information we cover in following chapters. We’ll show that husband/wife marriage and sexual monogamy are far from universal human behaviors, as she and others have argued. Simply because bonobos raise doubts about the naturalness of human long-term pair bonding, Fisher and most other authorities conclude that they cannot serve as models for human evolution. They begin by assuming that long-term sexual monogamy forms the nucleus of the one and only natural, eternal human family structure and reason backwards from there. Yucatán be damned!

I sometimes try to imagine what would have happened if we’d known the bonobo first and chimpanzee only later or not at all. The discussion about human evolution might not revolve as much around violence, warfare, and male dominance, but rather around sexuality, empathy, caring, and cooperation. What a different intellectual landscape we would occupy!

FRANS DE WAAL, Our Inner Ape

The weakness of the “killer ape theory” of human origins becomes clear in light of what’s now known about bonobo behavior. Still, de Waal makes a good case that even without the data that became available in the 1970s, the many flaws in the chimp-fortified Hobbesian view eventually would have emerged. He calls attention to the fact that the theory confuses predation with aggression, assumes that tools originated as weapons, and depicts women as “passive objects of male competition.” He calls for a new scenario that “acknowledges and explains the virtual absence of organized warfare among today’s human foragers, their egalitarian tendencies, and generosity with information and resources across groups.”26

By projecting recent post-agricultural preoccupations with female fidelity into their vision of prehistory, many theorists have Flintstonized their way right into a cul-de-sac. Modern man’s seemingly instinctive impulse to control women’s sexuality is not an intrinsic feature of human nature. It is a response to specific historical socioeconomic conditions—conditions very different from those in which our species evolved. This is key to understanding sexuality in the modern world. De Waal is correct that this hierarchical, aggressive, and territorial behavior is of recent origin for our species. It is, as we’ll see, an adaptation to the social world that arose with agriculture.

From our perspective on the far bank, Helen Fisher, Frans de Waal, and a few others seem to have ventured out onto the bridge that crosses over the rushing stream of unfounded assumptions about human sexuality—but they dare not cross it. Their positions seem, to us, to be compromises that strain against the most parsimonious interpretation of data they know as well as anyone. Confronted with the unignorable fact that human beings sure don’t act like a monogamous species, they make excuses for our “aberrant” (yet perplexingly consistent) behavior. Fisher explains the phenomenon of worldwide marital breakdown by arguing that the pair bond evolved to last only until the infant grows to a child who can keep up with the foraging band without fatherly assistance. For his part, de Waal still argues that the nuclear family is “intrinsically human” and the pair-bond is “the key to the incredible level of cooperation that marks our species.” But

he then suggestively concludes that “our success as a species is intimately tied to the abandonment of the bonobo lifestyle and to a tighter control over sexual expressions.”27 “Abandonment?” Since it’s impossible to abandon what one never had, de Waal would presumably agree that hominid sexuality was, at some point, profoundly similar to that of the relaxed, promiscuous bonobo—although he never says so explicitly. Nor has he ventured to say when or why our ancestors abandoned that way of being.28

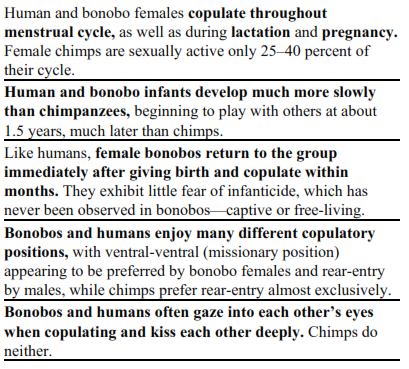

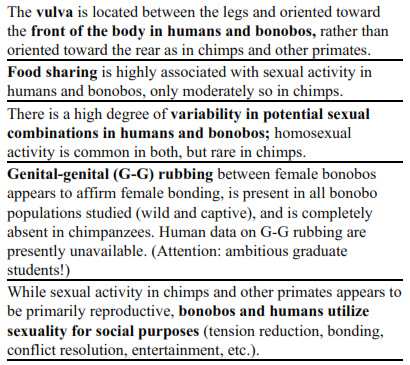

Table 2: Comparison of Bonobo, Chimp, and Human Socio-sexual Behavior and Infant Development29