Bonobo Beginnings

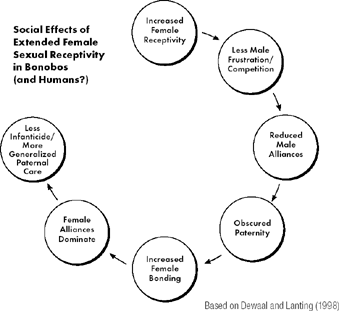

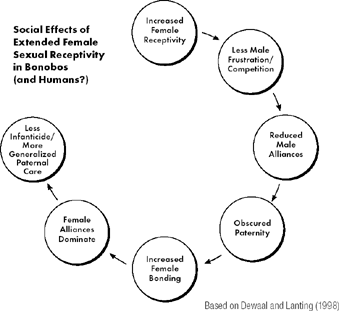

The effectiveness of sexual egalitarianism is confirmed by female bonobos, who share many otherwise unique traits with humans and no other species. These sexual characteristics have direct, predictable social consequences. De Waal’s research has demonstrated, for example, that the increased sexual receptivity of the female bonobo dramatically reduces male conflict, when compared with other primates whose females are significantly less sexually available. The abundance of sexual opportunity makes it less worthwhile for males to risk injury by fighting over any particular sexual opportunity. Since alliances among male chimps, for example, generally serve to keep competitors away from an ovulating female, or to attain the high status that brings more mating opportunities to a given male, the principal motivation for these unruly gangs evaporates in the relaxing heat of bonobos’ plentiful sexual opportunity.

These same dynamics apply to human groups. Aside from “the social habits of man as he now exists,” why presume the monogamous pair-based model of human evolution currently favored would have been adaptive for early humans, but not for bonobos in the jungles of central Africa? Unconstrained by cultural restrictions, the so-called continual responsiveness of the human female would fulfill the same function: provide plentiful sexual opportunity for males, thereby reducing conflict and allowing larger group sizes, more extensive cooperation, and greater security for all. As anthropologist Chris Knight puts it, “Whereas the basic primate pattern is to deliver a periodic ‘yes’ signal against a background of continuous sexual ‘no’, humans [and bonobos] emit a periodic ‘no’ signal against a background of continuous

‘yes’.”24Here we have the same behavioral and physiological adaptation, unique to two very closely related primates, yet many theorists insist the adaptation must have completely different origins and functions in each.

Based on Dewaal and Lanting (1998)

This increased social cohesion is, in fact, probably the most common explanation for the potent combination of extended receptivity and hidden ovulation found only in humans and bonobos.25 But most scientists seem to see only half of this logical connection, as in this abstract: “Females who concealed ovulation were favored because the group in which they lived maintained a peaceful stability that facilitated monogamy, sharing and cooperation.”26 It’s clear how greater female sexual availability could increase sharing, cooperation, and peaceful stability, but why monogamy should be added to the list is a question that not only goes unanswered but is almost never asked.

Those anthropologists willing to acknowledge the realities of human sexuality see its social benefits clearly. Beckerman and Valentine point to the fact that partible paternity defuses potential conflicts between men, noting that such antagonisms tend to be unhelpful to a woman’s long-term reproductive interests. Anthropologist Thomas Gregor reported eighty-eight ongoing affairs among the thirty-seven adults in the Mehinaku village he studied in Brazil. In his opinion, extramarital relationships “contribute to village cohesion,” by “consolidating relationships between persons of different [clans]” and “promoting enduring relationships based on mutual affection.” He found that “many lovers are very fond of one another and regard separation as a privation to avoid.”27

Rather than risk overwhelming you with dozens more examples of this community-building, conflict-reducing human sexuality, we’ll conclude with just one more. Anthropologists William and Jean Crocker visited and studied the Canela people—also of the Brazilian Amazon region—for more than three decades, beginning in the late 1950s. They explain:

It is difficult for members of a modern individualistic society to imagine the extent to which the Canela saw the group and the tribe as more important than the individual. Generosity and sharing was the ideal, while withholding was a social evil. Sharing possessions brought esteem. Sharing one’s body was a direct corollary. Desiring control over one’s goods and self was a form of stinginess. In this context, it is easy to understand why women chose to please men and why men chose to please women who expressed strong sexual needs. No one was so self-important that satisfying a fellow tribesman was less gratifying than personal gain [emphasis in original].28

Recognized as a way to build and maintain a network of mutually beneficial relationships, nonreproductive sex no longer requires special explanations. Homosexuality, for example, becomes far less confusing, in that it is, as E. O. Wilson has written, “above all a form of bonding … consistent with the greater part of heterosexual behavior as a device that cements relationships.”29

Paternity certainty, far from being the universal and overriding obsession of all men everywhere and always, as the standard narrative insists, was likely a nonissue to men who lived before agriculture and resulting concerns with passing property through lines of paternal descent.

* In a personal communication, Don Pollock makes an interesting point about the notion of multiple fatherhood, writing, “I have always found the Kulina notion that more than one man may be a ‘biological’ father to a child to be, ironically, similar to the genetic reality: in a small, genetically homogeneous population (or close to it, after many generations of in-marrying), every child has close genetic similarities to all of the men with whom his or her mother had sexual relations—even to those the mother was not involved with.”