CHAPTER ELEVEN

“The Wealth of Nature” (Poor?)

The point is, ladies and gentleman, that greed, for lack of a better word, is good. Greed is right, greed works. Greed clarifies, cuts through, and captures the essence of the evolutionary spirit. Greed, in all of its forms … has marked the upward surge of mankind.

“GORDON GEKKO,” in the film Wall Street

What constitutes misuse of the universe? This question can be answered in one word: greed…. Greed constitutes the most grievous wrong.

LAURENTI MAGESA,

African Religion: The Moral Traditions of Abundant Life

Economics, “the dismal science,” was dismal right from the start.

On a late autumn afternoon in 1838, what may have been the brightest bolt of illumination ever to flash out of an overcast English sky struck Charles Darwin right upside the head, leaving him stunned by what Richard Dawkins has called “the most powerful idea that has ever occurred to a man.” At the very moment the great insight underlying natural selection came to him, Darwin was reading An Essay on the Principle of Population by Thomas Malthus.1

If the measure of an idea is its endurance through time, Thomas Malthus deserves his spot as Wikipedia’s eightieth Most Influential Person in History. More than two centuries later, one would be hard pressed to find a single student of economics unfamiliar with the simple argument put forth by the world’s first professor of economics. You’ll recall that Malthus argued that each generation doubles geometrically (2, 4, 8, 16, 32 …), but farmers can only increase food supply arithmetically, as new fields are cleared and productive capacity is added in a linear fashion (2, 3, 4, 5, 6 …). From this crystalline reasoning follows Malthus’s brutal conclusion: chronic overpopulation, desperation, and widespread starvation are intrinsic to human existence. Not a thing to be done about it. Helping the poor is like feeding London’s pigeons; they’ll just reproduce back to the brink of starvation anyway, so what’s the point? “The poverty and misery which prevail among the lower classes of society,” Malthus asserts, “are absolutely irremediable.”

Malthus based his estimates of human reproductive rates on the recorded increase of (European) population in North America in the previous 150 years (1650–1800). He concluded that the colonial population had doubled every twenty-five years or so, which he took to be a reasonable estimate of the rates of human population growth in general.

In his autobiography, Darwin recalled that when he applied these dire Malthusian computations to the natural world, “it at once struck me that under these circumstances favorable variations would tend to be preserved, and unfavorable ones to be destroyed. The result of this would be the formation of new species. Here then I had at last got a theory by which to work …”2 Science writer Matt Ridley believes Malthus taught Darwin the “bleak lesson” that “overbreeding must end in pestilence, famine or violence,” convincing him that the secret of natural selection was embedded in the struggle for existence.

Thus was Darwin’s brilliance sparked by the darkest Malthusian gloom.3 Alfred Russel Wallace, who came up with the mechanism underlying natural selection independently of Darwin, experienced his own flash of insight while reading the same essay between bouts of fever in a hut on the banks of a malarial Malaysian river. Irish playwright George Bernard Shaw smelled the Malthusian morbidity underlying natural selection, lamenting, “When its whole significance dawns on you, your heart sinks into a heap of sand within you.” Shaw lamented natural selection’s “hideous fatalism,” and complained of its “damnable reduction of beauty and intelligence, of strength and purpose, of honor and aspiration.”4

But while Darwin and Wallace made excellent use of the Malthus’s dire calculations, there’s a problem with them. They don’t add up.

The tribes of hunters, like beasts of prey, whom they resemble in their mode of subsistence, will… be thinly scattered over the surface of the earth. Like beasts of prey, they must either drive away or fly from every rival, and be engaged in perpetual contests with each other…. The neighboring nations live in a perpetual state of hostility with each other. The very act of increasing in one tribe must be an act of aggression against its neighbors, as a larger range of territory will be necessary to support its increased numbers…. The life of the victor depends on the death of the enemy.

THOMAS MALTHUS,

An Essay on the Principle of Population

If his estimates of population growth were even close to correct, Malthus (and thus, Darwin) would have been right to assume that human societies had long been “necessarily confined in room,” resulting in “a perpetual state of hostility” with one another. In Descent of Man, Darwin revisits Malthus’s calculations, writing, “Civilised populations have been known under favourable conditions, as in the United States, to double their numbers in twenty-five years … [At this] rate, the present population of the United States (thirty millions), would in 657 years cover the whole terraqueous globe so thickly, that four men would have to stand on each square yard of surface.”5

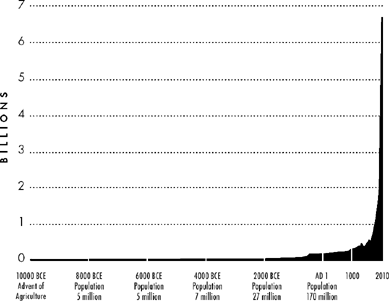

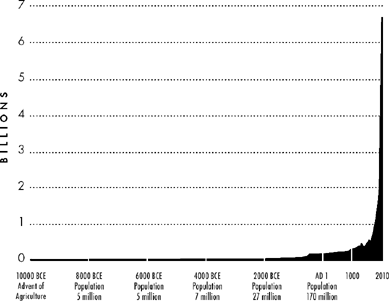

If Malthus had been correct about prehistoric human population doubling every twenty-five years, these assumptions would indeed have been reasonable. But he wasn’t, and they weren’t. We now know that until the advent of agriculture, our ancestors’ overall population doubled not every twenty-five years, but every 250,000 years. Malthus (and thus, Darwin after him) was off by a factor of 10,000.6

Malthus assumed the suffering he saw around him reflected the eternal, inescapable condition of human and animal life.

He didn’t understand that the teeming, desperate streets of London circa 1800 were far from a reflection of prehistoric conditions. A century and a half earlier, Thomas Hobbes had made the same mistake, extrapolating from his own personal experience to conjure a mistaken vision of prehistoric human life.

Estimated Global Population7

Thomas Hobbes was born to terror. His mother had gone into premature labor upon hearing that the Spanish Armada was about to attack England. “My mother,” Hobbes wrote many years later, “gave birth to twins: myself and fear.” Leviathan, the book in which he famously asserts that prehistoric life was “solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short,” was composed in Paris, where he was hiding from enemies he’d made by supporting the Crown in the English Civil War. The book was nearly abandoned when he was taken with a near-fatal illness that left him at death’s door for six months. Upon publication of Leviathan in France, Hobbes’s life was now being threatened by his fellow exiles, who were offended by the anti-Catholicism expressed in the book. He fled back across the channel to England, begging the mercy of those he’d escaped eleven years earlier. Though he was permitted to stay, publication of his book was prohibited. The Church banned it. Oxford University banned it and burned it. Writing of Hobbes’s world, cultural historian Mark Lilla describes “Christians addled by apocalyptic dreams [who] hunted and killed Christians with a maniacal fury they had once reserved for Muslims, Jews and heretics. It was madness.”8

Hobbes took the madness of his age, considered it “normal,” and projected it back into prehistoric epochs of which he knew next to nothing. What Hobbes called “human nature” was a projection of seventeenth-century Europe, where life for most was rough, to put it mildly. Though it has persisted for centuries, Hobbes’s dark fantasy of prehistoric human life is as valid as grand conclusions about Siberian wolves based on observations of stray dogs in Tijuana.

To be fair, Malthus, Hobbes, and Darwin were constrained by the lack of actual data. To his enormous credit, Darwin recognized this and tried hard to address it—spending his entire adult life collecting specimens, taking copious notes, and corresponding with anyone who could provide him with useful information. But it wasn’t enough. The necessary facts wouldn’t be revealed for many decades.

But now we have them. Scientists have learned to read ancient bones and teeth, to carbon-date the ash of Pleistocene fires, to trace the drift of the mitochondrial DNA of our ancestors. And the information they’ve uncovered resoundingly refutes the vision of prehistory Hobbes and Malthus conjured and Darwin swallowed whole.

Poor, Pitiful Me

We are enriched not by what we possess, but by what we can do without.

IMMANUEL KANT

If George Orwell was correct that “those who control the past control the future,” what of those who control the distant past?

Prior to the population increases associated with agriculture, most of the world was a vast, empty place in terms of human population. But the desperate overcrowding imagined by Hobbes, Malthus, and Darwin is still deeply embedded in evolutionary theory and repeated like a mantra, facts be damned. For example, in his recent essay entitled “Why War?,” philosopher David Livingstone Smith projects the Malthusian panorama in all its mistaken despair: “Competition for limited resources is the engine of evolutionary change,” he writes. “Any population that reproduces without inhibition will eventually outstrip the resources upon which it depends and, as numbers swell, individuals will have no alternative but to compete more and more desperately for dwindling resources. Those who can secure them will flourish, and those who cannot will die.”9

True, as far as it goes. But it doesn’t go very far, because Smith forgets that our ancestors were the original ramblin’ men (and women)—nomads who rarely stopped walking for more than a few days at a stretch. Walking away is what they did best. Why assume they would have stuck around to struggle “desperately” in an overpopulated area with depleted resources when they could simply walk up the beach, as they’d been doing for uncounted generations? And prehistoric human beings never reproduced “without inhibition,” like rabbits. Far from it. In fact, prehistoric world population growth is estimated to have been well below .001 percent per year throughout prehistory10—hardly the population bomb Malthus assumed.

Basic human reproductive biology in a foraging context made rapid population growth unlikely, if not impossible. Women rarely conceive while breastfeeding, and without milk from domesticated animals, hunter-gatherer women typically breastfeed each child for five or six years. Furthermore, the demands of a mobile hunter-gatherer lifestyle make carrying more than one small child at a time unreasonable for a mother—even assuming lots of help from others. Finally, low body-fat levels result in much later menarche for hunter-gatherer females than for their post-agricultural sisters. Most foragers don’t start ovulating until their late teens, resulting in a shorter reproductive life.11

Hobbes, Malthus, and Darwin were themselves surrounded by the desperate effects of population saturation (rampant infectious disease, ceaseless war, Machiavellian struggles for power). The prehistoric world, however, was sparsely populated—where it was populated at all. Other than isolated pockets surrounded by desert, or islands like Papua New Guinea, the prehistoric world was almost all open frontier. Most scholars believe that our ancestors were just setting out from Africa about fifty thousand years ago, entering Europe five or ten thousand years later.12 The first human footprints probably weren’t left on North American soil until about twelve thousand years ago.13 During the many millennia before agriculture, the entire number of Homo sapiens on the planet probably never surpassed a million people and certainly never approached the current population of Chicago. Furthermore, recently obtained DNA analyses suggest several population bottlenecks caused by environmental catastrophes reduced our species to just a few hundred individuals as recently as 70,000 years ago.14

Ours is a very young species. Few of our ancestors faced the unrelenting scarcity-generated selective pressures envisioned by Hobbes, Malthus, and Darwin. The ancestral human journey did not, by and large, take place in a world already saturated with our kind, fighting over scraps. Rather, the route taken by the bulk of our ancestors led through a long series of ecosystems with nothing quite like us already there. Like the Burmese pythons recently set loose in the Everglades, cane toads spreading unchecked across Australia, or the timber wolves recently reintroduced to Yellowstone, our ancestors were generally entering an open ecological niche. When Hobbes wrote that “Man to Man is an arrant Wolfe,” he was unaware of just how cooperative and communicative wolves can be if there’s enough food for everyone. Individuals in species spreading into rich new ecosystems aren’t locked in a struggle to the death against one another. Until the niche is saturated, such intraspecies conflict over food is counterproductive and needless.15

We’ve already shown that even in a largely empty world, the social lives of foragers were anything but solitary. But Hobbes also claimed prehistoric life was poor, and Malthus believed poverty to be eternal and inescapable. Yet most foragers don’t believe themselves to be impoverished, and there’s every indication that life wasn’t generally much of a struggle for our fire-controlling, highly intelligent ancestors bound together in cooperative bands. To be sure, occasional catastrophes such as droughts, climatic shifts, and volcanic eruptions were devastating. But most of our ancestors lived in a largely unpopulated world, chock-full of food. For hundreds of thousands of generations, the omnivore’s dilemma facing our ancestors lay in choosing among many culinary options. Plants eat soil; deer eat plants; cougars eat deer. But people can and do eat almost anything—including cougars, deer, plants, and yes, even soil.16