On Paleolithic Politics

Prehistoric life involved a lot of napping. In his provocative essay “The Original Affluent Society,” Sahlins notes that among foraging people, “the food quest is so successful that half the time the people do not seem to know what to do with themselves.”16 Even Australian Aborigines living in apparently unforgiving and empty country had no trouble finding enough to eat (as well as sleeping about three hours per afternoon in addition to a full night’s rest). Richard Lee’s research with !Kung San bushmen of the Kalahari Desert in Botswana indicates that they spend only about fifteen hours per week getting food. “A woman gathers on one day enough food to feed her family for three days, and spends the rest of her time resting in camp, doing embroidery, visiting other camps, or entertaining visitors from other camps. For each day at home, kitchen routines, such as cooking, nut cracking, collecting firewood, and fetching water, occupy one to three hours of her time. This rhythm of steady work and steady leisure is maintained throughout the year.”17

A day or two of light work followed by a day or two off. How’s that sound?

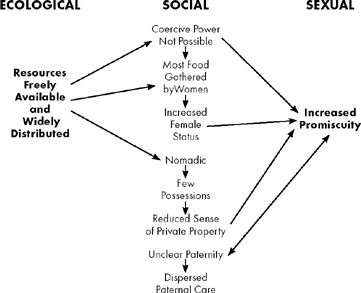

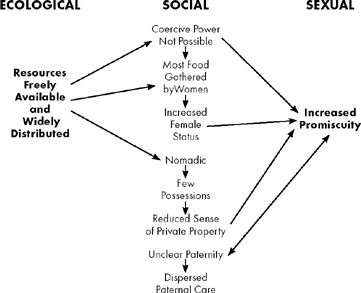

Because food is found in the surrounding environment, no one can control another’s access to life’s necessities in hunter-gatherer society. Harris explains that in this context, “Egalitarianism is … firmly rooted in the openness of resources, the simplicity of the tools of production, the lack of non-transportable property, and the labile structure of the band.”18

When you can’t block people’s access to food and shelter, and you can’t stop them from leaving, how can you control them? The ubiquitous political egalitarianism of foraging people is rooted in this simple reality. Having no coercive power, leaders are simply those who are followed—individuals who have earned the respect of their companions. Such “leaders” do not—cannot—demand anyone’s obedience. This insight is not breaking news. In his Lectures on Jurisprudence, which was published posthumously in 1896, Adam Smith wrote, “In a nation of hunters there is properly no government at all…. [They] have agreed among themselves to keep together for their mutual safety, but they have no authority one over another.”

It’s not surprising that conservative evolutionary psychologists have found foragers’ insistence on sharing to be one of their most difficult nuts to crack. Given the iconic status of Dawkins’s book The Selfish Gene and the popularized, status-quo protective notion of the all-against-all struggle for survival, the quest to explain why foraging people are so maddeningly generous to one another has occupied dozens of authors. In The Origins of Virtue, science writer Matt Ridley summarizes the inherent contradiction they face: “Our minds have been built by selfish genes, but they have been built to be social, trustworthy and cooperative.”19 One must walk a tightrope to insist that selfishness is (and has always been) the principal engine of human evolution even in the face of copious data demonstrating that human social organization was founded upon an impulse for sharing for many millennia.

Of course, this conflict would evaporate if proponents of the always-selfish theory of human nature accepted contextual limits to their argument. In other words, in a zero-sum context (like that of modern capitalist societies where we live among strangers), it makes sense, on some levels, for individuals to look out for themselves. But in other contexts human behavior is characterized by an equal instinct toward generosity and justice.20

Even if many of his followers prefer to ignore the subtleties of his arguments, Dawkins himself appreciates them fully, writing, “Much of animal nature is indeed altruistic, cooperative and even attended by benevolent subjective emotions…. Altruism at the level of the individual organism can be a means by which the underlying genes maximize their self-interest.”21 Despite famously inventing the concept of the “selfish gene,” Dawkins sees group cooperation as a way to advance an individual’s agenda (thereby advancing each individual’s genetic interests). Why, then, are so many of his admirers unwilling to entertain the notion that cooperation among human beings and other animals may be every bit as natural and effective as short-sighted selfishness?

Nonhuman primates offer intriguing evidence of the “soft power of peace”—and not just horny bonobos, either. Frans de Waal and Denise Johanowicz devised an experiment to see what would happen when two different macaque species were placed together for five months. Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) are aggressive and violent, while stump-tails (Macaca arctoides) are known for their more chilled-out approach to life. The stump-tails, for example, make up after conflict by gripping each other’s hips, whereas reconciliations are rarely witnessed among rhesus monkeys. Once the two species were placed together, however, the scientists saw that the more peaceful, conciliatory behavior of the stump-tails dominated the more aggressive rhesus attitudes. Gradually, the rhesus monkeys relaxed. As de Waal recounts, “Juveniles of the two species played together, groomed together, and slept in large, mixed huddles. Most importantly, the rhesus monkeys developed peacemaking skills on a par with those of their more tolerant group mates.” Even when the experiment concluded, and the two species were once again housed only with their own kind, the rhesus monkeys were still three times more likely to reconcile after conflict and groom their rivals.22

A fluke? Neuroscientist/primatologist Robert Sapolsky has spent decades observing a group of baboons in Kenya, starting when he was a student in 1978. In the mid-1980s, a significant proportion of adult males in the group abruptly died of tuberculosis they’d picked up from infected food in a dump outside a tourist hotel. But the prized (albeit infected) dump food had been eaten only by the most belligerent baboons, who had driven away less aggressive males, females, or juveniles. Justice! With all the hard-ass males gone, the laid-back survivors were in charge. The defenseless troop was a treasure ready-made for pirates: a whole troop of females, sub-adults, and easily cowed males just waiting for some neighboring tough guys to waltz in and start raping and pillaging.

Because male baboons leave their natal troop at adolescence, within a decade of the dump cataclysm, none of the original, atypically mellow males were still around. But, as Sapolsky reports, “the troop’s unique culture was being adopted by new males joining the troop.” In 2004, Sapolsky reported that two decades after the tuberculosis “tragedy,” the troop still showed higher-than-normal rates of males grooming and affiliating with females, an unusually relaxed dominance hierarchy, and physiological evidence of lower-than-normal anxiety levels among the normally stressed-out low-ranking males. Even more recently, Sapolsky told us that as of his most recent visit, in the summer of 2007, the troop’s unique culture appeared to be intact.23

In Hierarchy in the Forest, primatologist Christopher Boehm argues that egalitarianism is an eminently rational, even hierarchical political system, writing, “Individuals who otherwise would be subordinated are clever enough to form a large and united political coalition, and they do so for the express purpose of keeping the strong from dominating the weak.” According to Boehm, foragers are downright feline in refusing to follow orders, writing, “Nomadic foragers are universally—and all but obsessively—concerned with being free of the authority of others.”24

Prehistory must have been a frustrating time for megalomaniacs. “An individual endowed with the passion for control,” writes psychologist Erich Fromm, “would have been a social failure and without influence.”25

What if—thanks to the combined effects of very low population density, a highly omnivorous digestive system, our uniquely elevated social intelligence, institutionalized sharing of food, casually promiscuous sexuality leading to generalized child care, and group defense—human prehistory was in fact a time of relative peace and prosperity? If not a “Golden Age,” then at least a “Silver Age” (“Bronze Age” being taken)? Without falling into dreamy visions of paradise,

can we—dare we—consider the possibility that our ancestors lived in a world where for most people, on most days, there was enough for everyone? By now, everyone knows “there’s no free lunch.” But what would it mean if our species evolved in a world where every lunch was free? How would our appreciation of prehistory (and consequently, of ourselves) change if we saw that our journey began in leisure and plenty, only veering into misery, scarcity, and ruthless competition a hundred centuries ago?

Difficult as it may be for some to accept, skeletal evidence clearly shows that our ancestors didn’t experience widespread, chronic scarcity until the advent of agriculture. Chronic food shortages and scarcity-based economies are artifacts of social systems that arose with farming. In his introduction to Limited Wants, Unlimited Means, Gowdy points to the central irony: “Hunter-gatherers … spent their abundant leisure time eating, drinking, playing, socializing—in short, doing the very things we associate with affluence.”

Despite no solid evidence to support it, the public hears little to dispute this apocalyptic vision of prehistory. The sense of human nature intrinsic to Western economic theory is mistaken. The notion that humans are driven only by self-interest is, in Gowdy’s words, “a microscopically small minority view among the tens of thousands of cultures that have existed since Homo sapiens emerged some 200,000 years ago.” For the vast majority of human generations that have ever lived, it would have been unthinkable to hoard food when those around you were hungry. “The hunter-gatherer,” writes Gowdy, “represents uneconomic man.”26

Remember, even those “wretched” inhabitants of Tierra del Fuego, condemned to “the bottom of the scale of human beings,” threw down their hoes and walked away from their gardens once the HMS Beagle sailed out of sight. They knew firsthand how “civilized” people lived, yet they had “not the least wish to return to England.” Why would they? They were “happy and contented” with “plenty fruits,” “plenty fish,” and “plenty birdies.”