CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Little Big Man

Every creature’s body tells a detailed story about the environment in which its ancestors evolved. Its fur, fat, and feathers suggest the temperatures of ancient environments. Its teeth and digestive system contain information about primordial diet. Its eyes, legs, and feet show how its ancestors got around. The relative sizes of males and females and the particulars of their genitalia say a lot about reproduction. In fact, male sexual ornaments (such as peacock’s tails or lions’ manes) and genitals offer the best way to differentiate between closely related species. Evolutionary psychologist Geoffrey F. Miller goes so far as to say that “evolutionary innovation seems focused on the details of penis shape.”1

Leaving aside for the moment the disturbingly Freudian notion that even Mother Nature is obsessed with the penis, our bodies certainly contain a wealth of information about the sexual behavior of our species over the millennia. There are clues encoded in skeletal remains millions of years old and pulsing in our own living bodies. It’s all right there—and here. Rather than closing our eyes and dreaming, let’s open them and learn to read the hieroglyphics of the sexual body.

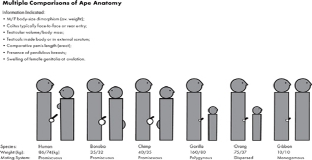

We begin with body-size dimorphism. This technical-sounding term simply refers to the average difference in size between adult males and females in a given species. Among apes for example, male gorillas and orangutans average about twice the size of females, while male chimps, bonobos, and humans are from 10 to 20 percent bigger and heavier than females. Male and female gibbons are of equal stature.

Among mammals generally and particularly among primates, body-size dimorphism is correlated with male competition over mating.2 In winner-take-all mating systems where males compete with each other over infrequent mating opportunities, the larger, stronger males tend to win … and take all. The biggest, baddest gorillas, for example, will pass genes for bigness and badness into the next generation, thus leading to ever bigger, badder male gorillas—until the increased size eventually runs into another factor limiting this growth.

On the other hand, in species with little struggle over females, there is less biological imperative for the males to evolve larger, stronger bodies, so they generally don’t. That’s why the sexually monogamous gibbons are virtually identical in size.

Looking at our modest body-size dimorphism, it’s a good bet that males haven’t been fighting much over females in the past few million years. As mentioned above, men’s bodies are from 10 to 20 percent bigger and heavier than women’s on average, a ratio that appears to have held steady for at least several million years.3

Owen Lovejoy has long argued that this ratio is evidence of the ancient origins of monogamy. In an article he published in Science in 1981, Lovejoy argued that both the accelerated brain development of our ancestors and their use of tools resulted from an “already established hominid character system,” that featured “intensified parenting and social relationships, monogamous pair bonding, specialized sexual-reproductive behavior, and bipedality.” Thus, Lovejoy argued, “The nuclear family and human sexual behavior may have their ultimate origin long before the dawn of the Pleistocene.” In fact, he concluded with a flourish, the “unique sexual and reproductive behavior of man may be the sine qua non of human origin.” Almost three decades later, Lovejoy is still pushing the same argument as this book goes to press. He argues—again in Science—that Ardipithecus ramidus’ fragmentary skeletal and dental remains dated to 4.4 million years ago reinforce this view of pair bonding as the defining human characteristic—predating, even, our uniquely large neocortex.4

Like many theorists, Matt Ridley agrees with this ancient origin of monogamy, writing, “Long pair-bonds shackled each ape-man to its mate for much of its reproductive life.”

Four million years is an awful lot of monogamy. Shouldn’t these “shackles” be more comfortable by now?

Without access to the skeletal data on body-size dimorphism we have today, Darwin speculated that early humans may have lived in a harem-based system. But we now know that if Darwin’s conjecture were correct, contemporary men would be twice the size of women, on average. And, as we’ll discuss in the next section, another sure sign of a gorilla-like human past would be an embarrassing case of genital shrinkage.

Still, some continue to insist that humans are naturally polygynous harem-builders, despite the paucity of evidence supporting this argument. For example, Alan S. Miller and Satoshi Kanazawa claim that, “We know that humans have been polygynous throughout most of history because men are taller than women.” These authors go on to conclude that because “human males are 10 percent taller and 20 percent heavier than females, this suggests that, throughout history, humans have been mildly polygynous.”5

Their analysis ignores the fact that the cultural conditions necessary for some males to accumulate sufficient political power and wealth to support multiple wives and their children simply did not exist before agriculture. And males being moderately taller and heavier than females indicates reduced competition among males, but not necessarily “mild polygyny.” After all, those promiscuous cousins of ours, chimps and bonobos, reflect precisely the same range of male/female size difference while shamelessly enjoying uncounted sexual encounters with as many partners as they can drum up. No one claims the 10 to 20 percent body-size dimorphism seen in chimps and bonobos is evidence of “mild polygyny.” The assertion that the same physical evidence correlates to promiscuity in chimps and bonobos but indicates mild polygyny or monogamy in humans shows just how shaky the standard model really is.

For various reasons, prehistoric harems were unlikely for our species. The famed sexual appetites of Ismail the Bloodthirsty, Genghis Khan, Brigham Young, and Wilt Chamberlain notwithstanding, our bodies argue strongly against it. Harems result from the common male hunger for sexual variety and the post-agricultural concentration of power in the hands of a few men combined with low levels of female autonomy typical of agricultural societies. Harems are a feature of militaristic, rigidly hierarchical agricultural and pastoral cultures oriented toward rapid population growth, territorial expansion, and accumulation of wealth. Captive harems have never been reported in any immediate-return foraging society.

While our species’ shift to moderate body-size dimorphism strongly suggests that males found an alternative to fighting over mating opportunities millions of years ago, it doesn’t tell us what that alternative was. Many theorists have interpreted the shift as confirmation of a transition from polygyny to monogamy—but that conclusion requires us to ignore multimale-multifemale mating as an option for our ancestors. Yes, a one-man/one-woman system reduces competition among males, as the pool of available females isn’t being dominated by just a few men, leaving more women available for less desired men. But a mating system in which both males and females typically have multiple sexual relationships running in parallel reduces male mating competition just as effectively, if not more so. And given that both of the species closest to us practice multimale-multifemale mating, this seems by far the more likely scenario.

Why are scientists so reluctant to consider the implications of our two closest primate relatives displaying the same levels of body-size dimorphism we do? Could it be because neither is remotely monogamous? The only two “acceptable” interpretations of this shift in body-size dimorphism appear to be:

1. It indicates the origins of our nuclear family/sexually monogamous mating system. (Then why aren’t men and women the same size, like gibbons?)

2. It shows that humans are naturally polygynous but have learned to control the impulse, with mixed success. (Then why aren’t men twice the size of women, like gorillas?)

Note the assumption shared by both these interpretations: female sexual reticence. In both scenarios, female “honor” is intact. In the second interpretation, only the male’s natural fidelity is in doubt.

When the three most closely related apes exhibit the same degree of body-size dimorphism, shouldn’t we at least consider the possibility that their bodies reflect the same adaptations before we reach for farfetched, if emotionally reassuring, conclusions?

It’s time to go below the belt….

All’s Fair in Love and Sperm War

No case interested and perplexed me so much as the brightly colored hinder ends and adjoining parts of certain monkeys.

CHARLES DARWIN6

It seems men weren’t fighting much over dates for the past few million years (until agriculture), but that doesn’t mean Darwin was wrong about male sexual competition being of crucial importance in human evolution. Even among bonobos, who experience little to no overt conflict over sex, Darwinian selection takes place, but on a level Darwin himself probably never considered—or dared discuss publicly, anyway. Rather than male bonobos competing to see who gets lucky, they all get lucky, and then let their spermatozoa fight it out. Otto Winge, who was working with guppies in the 1930s, coined the term sperm competition. Geoffrey Parker, studying the decidedly unglamorous yellow dungfly, later refined the concept.

The idea is simple. If the sperm of more than one male are present in the reproductive tract of an ovulating female, the spermatozoa themselves compete to fertilize the ovum. Females of species that engage in sperm competition typically have various tricks to advertise their fertility, thereby inviting more competitors. Their provocations range from sexy vocalizations or scents to genital swellings that turn every shade of lipstick red from Berry Sexy to Rouge Soleil.7

The process is something of a lottery, where the male with the most tickets has the best shot at winning (hence, the chimp and bonobo’s huge sperm-production capabilities). It’s also an obstacle course, with the female’s body providing various types of hoops to jump through and moats to swim across to reach the egg—thus eliminating unworthy sperm. (We’ll examine some of these obstacles in following chapters.) Some researchers argue that the competition is more like rugby, with various sperm forming “teams” with specialized blockers, runners, and so on.8 Sperm competition takes many forms.

Although Darwin might have been “perplexed” by it, sperm competition preserves the central purpose of male competition in his theory of sexual selection, with the reward to the victor being fertilization of the ovum. But the struggle occurs on the cellular level, among the sperm cells, with the female’s reproductive tract the field of battle. Male apes living in multimale social groups (such as chimps, bonobos, and humans) have larger testes, housed in an external scrotum, mature later than females, and produce larger volumes of ejaculate containing greater concentrations of sperm cells than primates in which females normally mate with only one male per cycle (such as gorillas, gibbons, and orangutans).

And, who knows? Perhaps Darwin would have recognized this process, if he’d been a bit less indoctrinated by Victorian notions of female sexuality. Sarah Hrdy contends that “it was Darwin’s presumption that females hold themselves in reserve for the best available male that left him so puzzled by sexual swellings.” Hrdy doesn’t buy Darwin’s “coy female” schtick for a minute: “Although appropriate for many animals, the appellation ‘coy’—which was to remain unchallenged dogma for the succeeding hundred years—did not then, and does not today, apply to the observed behavior of monkey and ape females at mid-cycle.”9

It’s possible Darwin was being a bit coy himself in his writings on the sexuality of human females. The poor guy had already insulted God, as most people—including his loving, pious wife—understood the concept. Even if he suspected something like sperm competition had played a role in human evolution, Darwin could hardly be expected to drag the angelic Victorian woman down from her pedestal. Bad enough that Darwinian theory depicts women evolving to prostitute themselves for meat, access to male wealth, and the rest of it. To have argued that ancestral females were shameless trollops motivated by erotic pleasure would have been too much.

Still, with characteristic awareness of just how much he didn’t—and couldn’t—know, Darwin acknowledged, “As these parts are more brightly coloured in one sex [female] than in the other, and as they become more brilliant during the season of love, I concluded that the colours had been gained as a sexual attraction. I was well aware that I thus laid myself open to ridicule….”10

Perhaps Darwin did understand that the bright sexual swellings of some female primates served to stoke male libido, which shouldn’t be necessary according his sexual selection theory. There is even evidence that Darwin may have had reason to ponder sperm competition in humans. In a letter from Bhutan, where he was gathering plants, Darwin’s old friend Joseph Hooker discussed the polyandrous humans he was encountering, where “a wife may have 10 husbands by law.”

Moderate body-size dimorphism isn’t the only anatomical suggestion of promiscuity in our species. The ratio of testicular volume to overall body mass can be used to read the degree of sperm competition in any given species. Jared Diamond considers the theory of testis size to be “one of the triumphs of modern physical anthropology.”11 Like most great ideas, the theory of testis size is simple: species that copulate more often need larger testes, and species in which several males routinely copulate with one ovulating female need even bigger testes.

If a species has cojones grandes, you can bet that males have frequent ejaculations with females who sleep around. Where the females save it for Mr. Right, the males have smaller testes, relative to their overall body mass. The correlation of slutty females with big balled males appears to apply not only to humans and other primates, but to many mammals, as well as to birds, butterflies, reptiles, and fish.

In gorillas’ winner-take-all approach to mating, males compete to see who gets all the booty, as it were. So, although an adult silverback gorilla weighs in at around four hundred pounds, his penis is just over an inch long, at full mast, and his testicles are the size of kidney beans, though you’d have trouble finding them, as they’re safely tucked up inside his body. A one-hundred-pound bonobo has a penis three times as long as the gorilla’s and testicles the size of chicken eggs. The extra-large, AAA type (see chart on page 224). In bonobos, since everybody gets some sugar, the competition takes place on the level of the sperm cell, not at the level of the individual male. Still, although almost all bonobos are having sex, given the realities of biological reproduction, each baby bonobo still has only one biological father.

So the game’s still the same—getting one’s genes into the future—but the field of play is different. With harem-based polygynous systems like the gorilla’s, individual males fight it out before any sex takes place. In sperm competition, the cells fight in there so males don’t have to fight out here. Instead, males can relax around one another, allowing larger group sizes, enhancing cooperation, and avoiding disruption to the social dynamic. This helps explain why no primate living in multimale social groups is monogamous. It just wouldn’t work.

As always, natural selection targets the relevant organs and systems for adaptation. Through the generations, male gorillas evolved impressive muscles for their reproductive struggle, while their relatively unimportant genitals dwindled down to the bare minimum needed for uncontested fertilization. Conversely, male chimps, bonobos, and humans had less need for oversized muscles for fighting but evolved larger, more powerful testicles and, in the case of humans, a much more interesting penis.

We can almost hear some of our readers thinking, “But my testicles aren’t the size of chicken eggs!” No, they’re not. But we’re guessing they’re not tiny kidney beans tucked up inside your abdomen, either. Humans fall in the middle ground between gorillas and bonobos on the testicular volume/ body-mass scale. Those who argue that our species has been sexually monogamous for millions of years point out that human testicles are smaller than those of chimps and bonobos. Those who challenge the standard narrative (like us, for example) note that human testicular ratios are far beyond those of the polygynous gorilla or the monogamous gibbon.

So, is the human scrotum half-empty or half-full?