CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Sometimes a Penis Is Just a Penis

We are right to note the license and disobedience of this member which thrusts itself forward too inopportunely when we do not want it to, and which so inopportunely lets us down when we most need it; it imperiously contests for authority with our will: it stubbornly and proudly refuses all our incitements, both of the mind and hand.

MICHEL MONTAIGNE on the penis (his, presumably)

Don’t be distracted by the snickering. The human male takes his genitalia very seriously. In ancient Rome, rich boys wore a bulla: a locket holding a replica of a tiny hard-on. This rocket-in-a-locket was known as a fascinum, and signified the young man’s upper-class status. “Today,” writes David Friedman in A Mind of Its Own, his amusing and erudite history of the penis, “fifteen hundred years after the fall of Imperial Rome, anything as powerful or intriguing as an erection is said to be ‘fascinating.’” Going back a bit farther, we find that in the biblical books of Genesis and Exodus, Jacob’s children sprang from his thigh. Most historians agree that “thigh” is actually a polite way of referring to that which hangs between a man’s thighs. “It seems clear,” writes Friedman, “that sacred oaths between Israelites were sealed by placing a hand on the male member.” The act of swearing on one’s balls lives on in the word testify.

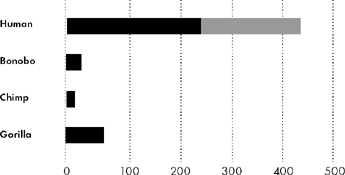

Historical oddities aside, some argue that moderately sized human testicles and lower human sperm concentration (relative to chimpanzees and bonobos) disprove any significant sperm competition in human evolution. True, the reported range of human sperm concentration of 60–235 × 106 per mL pales in comparison to that of chimps, an impressive 548 × 106. But not all sperm competition is created equal.

For example, some species have seminal fluid that forms a “copulatory plug,” serving to block the entrance of any subsequent sperm into the cervical canal. Species engaging in this type of sperm competition (snakes, rodents, some insects, kangaroos) typically wield penises with elaborate hooks or curlicues on the end that function to pull any previous male’s plug out of the cervical opening. Though at least one team of researchers reports data suggesting men who copulate frequently produce semen that coagulates for a longer time, copulatory plugs don’t appear to be in the human sexual arsenal.

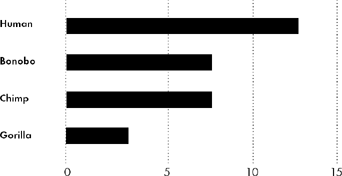

Despite its lack of curlicues, the human penis is not without interesting design features. Primate sexuality expert Alan Dixson writes, “In primates which live in family groups consisting of an adult pair plus offspring [such as gibbons] the male usually has a small and relatively unspecialized penis.” Say what you will about the human penis, but it ain’t small or unspecialized. Reproductive biologist Roger Short (real name) writes, “The great size of the erect human penis, in marked contrast to that of the Great Apes, makes one wonder what particular evolutionary forces have been at work.” Geoffrey Miller just comes out and says it: “Adult male humans have the longest, thickest, and most flexible penises of any living primate.”1 So there.

Homo sapiens: the great ape with the great penis!

The unusual flared glans of the human penis forming the coronal ridge, combined with the repeated thrusting action characteristic of human intercourse—ranging anywhere from ten to five hundred thrusts per romantic interlude—creates a vacuum in the female’s reproductive tract. This vacuum pulls any previously deposited semen away from the ovum, thus aiding the sperm about to be sent into action. But wouldn’t this vacuum action also draw away a man’s own sperm? No, because upon ejaculation, the head of the penis shrinks in size before any loss of tumescence (stiffness) in the shaft, thus neutralizing the suction that might have pulled his own boys back.2 Very clever.

Penis Lengths of African Apes (cm)

Intrepid researchers have demonstrated this process, known as semen displacement, using artificial semen made of cornstarch (the same recipe used to simulate exaggerated ejaculates in many pornographic films), latex vaginas, and artificial penises in a proper university laboratory setting. Professor Gordon G. Gallup and his team reported that more than 90 percent of the cornstarch mixture was displaced with just a single thrust of their lab penis. “We theorize that as a consequence of competition for paternity, human males evolved uniquely configured penises that function to displace semen from the vagina left by other males,” Gallup told BBC News Online.

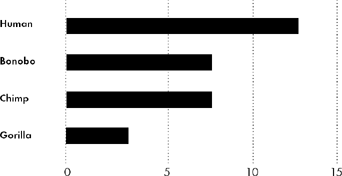

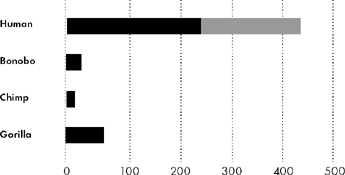

It bears repeating that the human penis is the longest and thickest of any primate’s—in both absolute and relative terms. And despite all the bad press they get, men last far longer in the saddle than bonobos (fifteen seconds), chimps (seven seconds), or gorillas (sixty seconds), clocking in between four and seven minutes, on average.

Average Copulation Duration (seconds)

The chimpanzee penis, meanwhile, is a thin, conical appendage without the flared glans of the human member. Nor is sustained thrusting common to chimpanzee or bonobo copulation. (But really, how much sustained anything can you expect in seven seconds?) So while our closest ape cousins may have us beat in the testicles department, they lose to the human penis on size, duration, and cool design features. Furthermore, the average seminal volume in a human ejaculate is about four times that of chimpanzees, bringing the total number of sperm cells per ejaculate within range of the chimp’s.

Returning to the question of whether the human scrotum is half-empty or half-full, the very existence of the external human scrotum suggests sperm competition in human evolution. Gorillas and gibbons, like most other mammals that don’t engage in sperm competition, generally aren’t equipped for it.3

A scrotum is like a spare refrigerator in the garage just for beer. If you’ve got a spare beer fridge, you’re probably the type who expects a party to break out at any moment. You want to be prepared. A scrotum fulfills the same function. By keeping the testicles a few degrees cooler than they would be inside the body, a scrotum allows chilled spermatozoa to accumulate and remain viable longer, available if needed.

Anyone who’s been kicked in the beer fridge can tell you this is a potentially costly arrangement. The increased vulnerability of having testes out there in the wind inviting attack or accident rather than tucked away safely inside the body is hard to overstate—especially if you’re crumpled in the fetal position, unable to breathe. Given the unrelenting logic of evolutionary cost/benefit analyses, we can be quite certain this is not an adaptation without good reason.4 Why carry the tools if you don’t have the job?

There is compelling evidence pointing to a dramatic reduction in human sperm production and testicular volume in recent times. Researchers have documented worrisome decreases in average sperm count as well as reduced vitality of the sperm that do survive. One researcher suggests that average sperm counts in Danish men have plummeted from 113 × 106 in 1940 to about half that in 1990 (66 × 106).5 The list of potential causes for the collapse is long, ranging from estrogen-like compounds in soybeans and the milk of pregnant cows to pesticides, fertilizers, growth hormones in cattle, and chemicals used in plastics. Recent research suggests the widely prescribed antidepressant paroxetine (sold as Seroxat or Paxil) may damage DNA in sperm cells.6 The Human Reproduction study at the University of Rochester found that men whose mothers had eaten beef more than seven times per week while pregnant were three times more likely to be classified as subfertile (fewer than twenty million sperm per milliliter of seminal fluid). Among these sons of beef eaters, the rate of subfertility was 17.7 percent, as opposed to 5.7 percent among men whose mothers ate beef less often.

Humans seem to have much more sperm-producing tissue than any monogamous or polygynous primate would need. Men produce only about one-third to one-eighth as much sperm per gram of spermato-genic tissue as eight other mammals tested.7 Researchers have noted similar surplus capacities in other aspects of human sperm and semen-production physiology.8

The correlation between infrequent ejaculation and various health problems offers further evidence that present-day men are not using their reproductive equipment to its fullest potential. A team of Australian researchers, for example, found that men who had ejaculated more than five times per week between the ages of twenty and fifty were one-third less likely to develop prostate cancer later in life.9 Along with the fructose, potassium, zinc, and other benign components of semen, trace amounts of carcinogens are often present, so researchers hypothesize that the reduction in cancer rates may be due to the frequent flushing of the ducts.

A different team from Sydney University reported in late 2007 that daily ejaculation dramatically reduced DNA damage to men’s sperm cells, thereby increasing male fertility—quite the opposite of the conventional wisdom. After forty-two men with damaged sperm were instructed to ejaculate daily for a week, almost all showed less chromosomal damage than a control group who had abstained for three days.10

Frequent orgasm is associated with better cardiac health as well. A study conducted at the University of Bristol and Queen’s University of Belfast found that men who have three or more orgasms per week are 50 percent less likely to die from coronary heart disease.11

Use it or lose it is one of the basic tenets of natural selection. With its relentless economizing, evolution rarely equips an organism for a task not performed. If contemporary levels of sperm and semen production were typical of our ancestors, it is unlikely our species would have evolved so much surplus capacity. Contemporary men have far more potential than they use. But if it’s true that modern human testicles are mere shadows of their former selves, what happened?

Since the infertile leave no descendants, it’s a truism in evolutionary theory that infertility can’t be inherited. But low fertility can be passed along under certain conditions. As discussed above, chromosomes in humans, chimps, and bonobos associated with sperm-producing tissue respond very rapidly to adaptive pressures—far more rapidly than other parts of the genome or the corresponding chromosomes in gorillas, for example.

In the reproductive environment we envision, characterized by frequent sexual interaction, females would typically have mated with multiple males during each ovulatory period, as do female chimps and bonobos. Thus, men with impaired fertility would have been unlikely to father children, as their sperm cells would have been overwhelmed by those of other sexual partners. The genes for robust sperm production are strongly favored in such an environment, while mutations resulting in decreased male fertility would have been filtered out of the gene pool, as they still are in chimps and bonobos.

But now consider the repercussions of culturally imposed sexual monogamy—even if enforced only for women, as was often the case until recently. In a monogamous mating system where a woman has sex with only one man, there is no sperm competition with other males. Sex becomes like an election in a dictatorship: just one candidate can win, no matter how few votes are cast. So, even a man with impaired sperm production is likely to ring the bell eventually, thus conceiving sons (and perhaps daughters) with increased potential for weakened fertility. In this scenario, genes associated with reduced fertility would no longer be removed from the gene pool. They’d spread, resulting in a steady reduction in overall male fertility and generalized atrophy of human sperm-production tissue.

Just as eyeglasses have allowed survival and reproduction for people with visual incapacities that would have doomed them (and their genes) in ancestral environments, sexual monogamy permits fertility-reducing mutations to proliferate, causing testicular diminishments that would never have lasted among our nonmonogamous ancestors. The most recent estimates show that sperm dysfunction affects about one in twenty men around the world, being the single most common cause of subfertilility in couples (defined as no pregnancy after a year of trying). Every indication is that the problem is growing steadily worse.12 Nobody’s maintaining the spare fridge much anymore, so it’s breaking down.

If our paradigm of prehistoric human sexuality is correct, in addition to environmental toxins and food additives, sexual monogamy may be a significant factor in the contemporary infertility crisis. Widespread monogamy may also help explain why, despite our promiscuous past, the testicles of contemporary Homo sapiens are smaller than those of chimps and bonobos and, as indicated by our excess sperm-production capacity, than those of our own ancestors.

Sexual monogamy itself may be shrinking men’s balls.

Perhaps we can declare an end to the standoff between those who argue that small human testicles tell “a story of romance and bonding between the sexes going back a long time, perhaps to the beginning of our lineage,” and those who contend that our slightly-larger-than-they-should-be-if-we’re-really-monogamous testicles indicate many millennia of “mild polygyny.” Humans have medium-size testicles by primate standards—with strong indications of recent dwindling—but can still produce ejaculates teeming with hundreds of millions of spermatozoa. Along with a penis adapted to sperm competition, human testicles strongly suggest ancestral females had multiple lovers within a menstrual cycle. Human testicles are the equivalent of drying apples on a November tree—shrinking reminders of days gone by.

As a way of testing this hypothesis, we should find that relative penis and testicle data differ among racial and cultural groups. These differences—theoretically due to significant and consistent differences in the intensity of sperm competition in recent historical times—are what we do find, if we dare to look.13

Because fit is so important in the effectiveness of condoms, World Health Organization guidelines specify different sizes for various parts of the world: a 49-millimeter-width condom for Asia, a 52-millimeter width for North America and Europe, and a 53-millimeter width for Africa (all condoms are longer than most men will ever need). The condoms manufactured in China for their domestic market are 49 millimeters wide. According to a study conducted by the Indian Council of Medical Research, high levels of slippage and failure are due to a bad fit between many Indian men and the international standards used in condom manufacture.14

According to an article published in Nature, Japanese and Chinese men’s testicles tend to be smaller than those of Caucasian men, on average. The authors of the study concluded that “differences in body size make only a slight contribution to these values.”15 Other researchers have confirmed these general trends, finding average combined testes weights of 24 grams for Asians, 29 to 33 grams for Caucasians, and 50 grams for Africans.16 Researchers found “marked differences in testis size among human races. Even controlling for age differences among samples, adult male Danes have testes that are more than twice the size of their Chinese equivalents, for example.”17 This range is far beyond what average racial differences in body size would predict. Various estimates conclude that Caucasians produce about twice the number of spermatozoa per day than do Chinese (185–235 × 106 compared with 84 × 106).

These are dangerous waters we’re swimming in, dear reader, suggesting that culture, environment, and behavior can be reflected in anatomy—genital anatomy, at that. But any serious biologist or physician knows there are anatomical differences expressed racially. Despite the hair-trigger sensitivity of these issues, not to consider racial background in the diagnosis and treatment of disease would be unethical.

Still, some of the reluctance to connect culturally sanctioned behavior with genital anatomy is as much due to the difficulty of finding reliable historical information about true rates of female promiscuity as to the emotionally charged nature of the material itself. Furthermore, diet and environmental factors would have to be factored in before arriving at any solid conclusions regarding the relationship between sexual monogamy and genital anatomy. For example, many Asian diets include large quantities of soy products, while many Western people consume large quantities of beef, both having been shown to cause rapid generational reduction in testicular volume and spermatogenesis. Given the controversial nature of such research, and the complexities of eliminating so many variables, perhaps it’s not surprising that this is an area few researchers are eager to enter.

There is a wide world of evidence that human sexual activity goes far beyond what’s needed for reproduction. While the social function of sex is now seen mainly in terms of maintaining the nuclear family, this is far from the only way societies channel human sexual energies to promote social stability.

Coming in at hundreds or thousands of copulations per child born, human beings outcopulate even chimpanzees and bonobos—and are far beyond gorillas and gibbons. When the average duration of each copulation is factored in, the sheer amount of time spent in sexual activity by human beings easily surpasses that of any other primate—even if we agree to ignore all our fantasizing, dreaming, and masturbating.

The evidence that sperm competition played a role in human evolution is simply overwhelming. In the words of one researcher, “Without sperm warfare during human evolution, men would have tiny genitals and produce few sperm…. There would be no thrusting during intercourse, no sex dreams or fantasies, no masturbation, and we would each feel like having intercourse only a dozen or so times in our entire lives…. Sex and society, art and literature—in fact, the whole of human culture—would be different.”18 We can add to this list the fact that men and women would be the same height and weight (if monogamous) or that men would likely be twice the size of women (if polygynous).

Just as Darwin’s famous finches in the Galápagos evolved different beak structures for cracking different seeds, related species often evolve different mechanisms for sperm competition. The sexual evolution of chimps and bonobos followed a strategy dependent upon repeated ejaculations of small but highly concentrated deposits of sperm cells, while humans evolved an approach featuring:

• a penis designed to pull back preexisting sperm, with extended, repeated thrusting;

• less frequent (compared to chimps and bonobos) but larger ejaculates;

• testicular volume and libido far beyond what’s needed for monogamous or polygynous mating;

• rapid-reaction DNA controlling development of testicular tissue, this DNA apparently being absent in monogamous or polygynous primates;

• overall sperm content per ejaculate—even today—in the range of chimps and bonobos; and

• the precarious location of the testicles in a vulnerable external scrotum, associated with promiscuous mating.

In Spanish, the word esperar can mean “to expect” or “to hope”—depending on context. “Archaeology,” writes Bogucki, “is very much constrained by what the modern imagination allows in the range of human behavior.”19 So is evolutionary theory. Perhaps so many still conclude that sexual monogamy is characteristic of our species’ evolutionary past, despite the clear messages inscribed in every man’s body and appetites, because this is what they expect and hope to find there.