Footnotes:

1. These deeds, and the greater part of others quoted in these memoirs, are preserved in the Chartulary of Cambray. Extracts from them were communicated by M. Mutte, dean of Cambray, to M. de Foncemagne, who lent, them to M. Dacier.

2. They are preserved in MS. by the regular canons of St Aubert in Cambray.

3. ‘This extract was published by M. Villaret in the xiith vol. of his ‘Histoire de France,’ edition in 12mo. page 119.’

4. ‘The text of Monstrelet is Pâques Communiaux. This expression has seemed to some learned men to be equally applicable to Palm as to Easter Sunday. M. Secousse, in a note on these words, which he has added to page 480 of the ixth volume of Ordinances, reports both opinions, without deciding on either. But the sense is absolutely determined as to Easter-day in this passage of Monstrelet, and in a paper quoted by du Chesne, among the proofs to the genealogy of the house of Montmorenci, p. 224. It is a receipt from Anthony de Waevrans, esquire, châtelain of Lille, with this date,—‘the 2d of April, on the vigil of Pâques communiaux avant la cierge benit, in the year 1490.’ The circumstance of the paschal taper clearly shows it to have been written on holy Saturday, which fell that year on the 2d of April, since Easter-day of 1491 was on the 3d of the same month.—See l’Art de Verifier les Dates.’

5. Essais de Montaigne, liv. xi. chap. 10.

6. I have a copy of these corrections, which are introduced either into the body of the text or at the bottom of the page.

7. ‘More slobbering than a mustard pot;’ but Cotgrave translates this, ‘Foaming at the mouth like a boar.’

8. ‘Having compared these different chronicles, underneath is the result.

|

The truces between England and France, from the

|

Grandes Chroniques.

|

|

|

|

Measures taken by the king of France relative to the troubles in the church, by the election of the duke of Savoy to the popedom,

|

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

Continuation of the same subject,

|

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

Taking of Fougeres,

|

Ditto, and in Jean Chartier.

|

|

|

|

Rebellion in London,

|

Ditto.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

Capture of Pont de l’Arche, &c.

|

Ditto.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

Events of War,

|

Ditto.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

From page 11. to page 23. in the original,

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

From page 141. to page 157.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

With this difference, that the continuator of Monstrelet omits to report the treaties of surrender of many towns, and that he sometimes inverts the order of events.

|

|

|

|

|

From page 29. to page 35. from the

|

Grandes Chroniques.

|

|

|

|

158. 164.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

35. 36.

|

Do. but somewhat abridged.

|

|

|

|

36. 38.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

165. 171.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

38. 40.

|

Ditto.

|

|

|

|

40.

|

Chronicles of Arras.’

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

9. From chapter ccxvii to ccxxxvi in the translation, third volume, 4to.

10. ‘The capture of Sandwich by the French has been twice told; and also the account of the embassy from Hungary,—the duke of Burgundy’s entry into Ghent,—the proceedings against the duke of Alençon,—the account of what passed at the funeral of king Charles VII.’

11. ‘The copy of this chronicle, whence D. Berthod made his extract, is (or perhaps rather was) in the royal library at Brussels. Pere le Long and M. de Fontette notice another copy in the abbey of St Waast at Arras. This must be the original, for D. Berthod told me, that the one at Brussels was a copy.’

12. ‘Vol. xvi. of the Memoires de l’Académie, page 251.’

13. See his preface at the head of the first volume, page 7.

14. Epistola plurium doctorum e societate Sorbonicâ ad illustrissimum marchionem Scipionem Maffeium, de ratione indicis Sorbonici, seu bibliothecæ alphabeticæ, quam adornant, &c. 1734.

15. This quaint expression is manifestly adopted from Froissart who uses it very often.

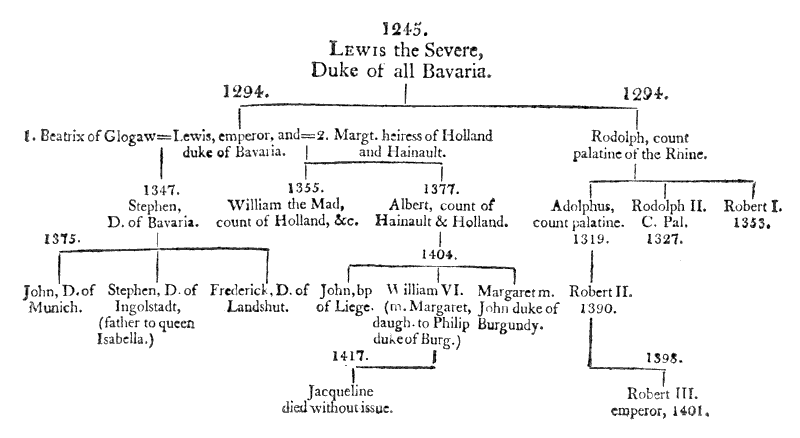

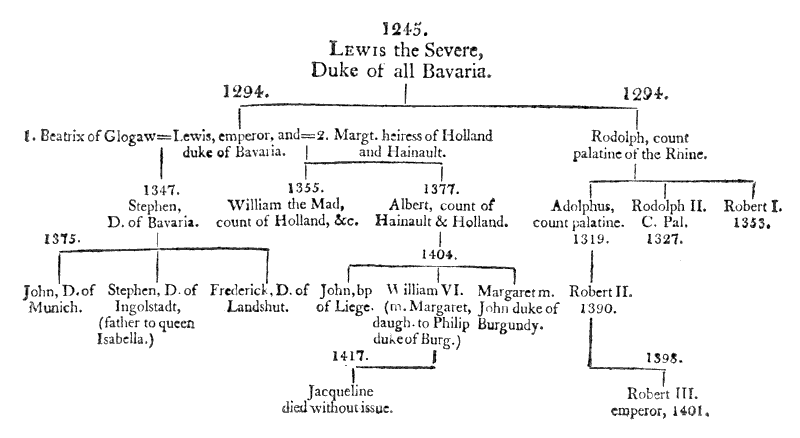

16. The house of Bavaria was at this period split into so many branches, the males of every branch retaining, according to the german custom, the title of the head of the house, that it becomes a difficult task to point out their several degrees of affinity without having recourse to a genealogical table. The following will suffice for the purpose of explaining Monstrelet:

17. Q. Luttrel, or Latimer?

18. The whole of this romantic passage seems to refer to the ancient courts of love, the institution of which was considerably prior to the fifteenth century.

19. The wars for the succession of Arragon had terminated two years previous to this, otherwise we should be at no loss to account for the business which forced Michel d’Orris to return from France.

20. The kings of Castille were at this period styled kings of Spain, κατ’ εξοχην.

21. This was the year of the jubilee. The plague raged at Rome, where, as Buoninsegni informs us, seven or eight hundred persons died daily. Few of the pilgrims returned. Many were murdered by the pope’s soldiers, an universal confusion prevailing at that time throughout Italy.

22. John V. duke of Brittany, had issue, by his several wives, John VI. his successor, Arthur count of Richemont and duke of Brittany in 1457, Giles de Chambon and Richard count of Estampes. His daughters were married to the duke of Alençon, count of Armagnac, viscount of Rohan, &c. John VI. married Joan of France, daughter of Charles VI.

23. Manuel Paleologus.

24. ‘The emperor of Constantinople came into Englande to require ayde against the Turkes, whome the king, with sumptuous preparation, met at Blacke-heath, upon St Thomas day the apostle, and brought him to London, and, paying for the charges of his lodging, presented him with giftes worthy of one of so high degree.’

STOWE, 326.

25. Waleran de Luxembourg III. count of St Pol, Ligny and Roussy, castellan of Lille, &c. &c. &c. a nobleman of very extensive and rich possessions, attached to the duke of Burgundy, through whose interest he obtained the posts of grand butler 1410, of governor of Paris and constable of France 1411. He died, 1415, leaving only one legitimate daughter, who, by marriage with Antony duke of Brabant, brought most of the family-possessions into the house of Burgundy.

26. Joan, daughter of Charles the bad, third wife of John V. Her mother was Joan of France, sister to Charles V. the duke of Burgundy, &c. Joan, duchess dowager of Bretagne, afterwards married Henry IV. of England.

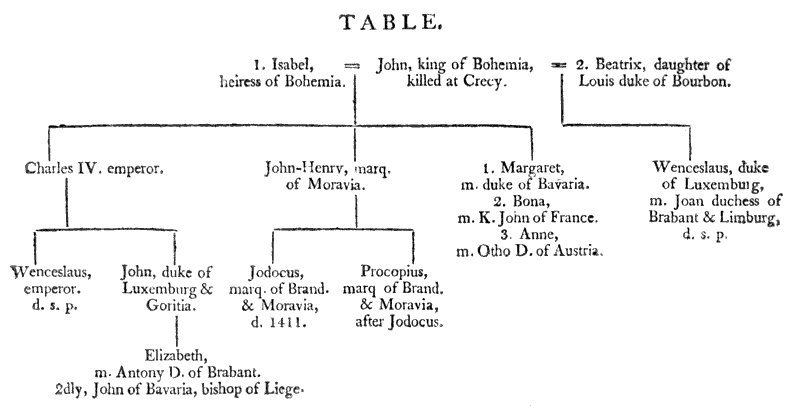

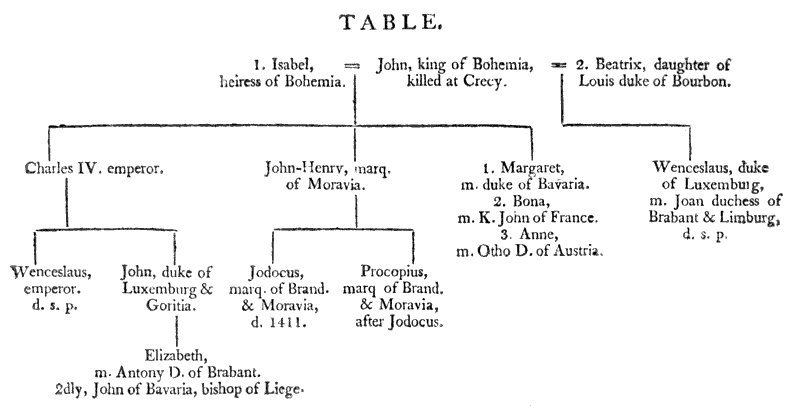

27. After the death of Wenceslaus duke of Brabant and Luxembourg (the great friend and patron of Froissart), the latter duchy reverted, of right, to the crown of Bohemia. But during the inactive and dissolute reign of the emperor Wenceslaus, it seems to have been alternately possessed by himself, by governors under him nominally, but in fact supreme, or by Jodocus M. of Brandenburg and Moravia, his cousin. In the history of Luxembourg by Bertelius, several deeds and instruments are cited, which tend rather to perplex than elucidate. But he gives the following account of the transaction with Louis duke of Orleans: ‘Wenceslaus being seldom in those parts, and greatly preferring Bohemia, his native country, granted the government of Luxembourg to his cousin the duke of Orleans; and moreover, for the sum of 56,337 golden crowns lent him by Louis, mortgaged to him the towns of Ivoy, Montmedy, Damvilliers and Orchiemont, with their appurtenances.’ In a deed of the year 1412, the duke of Orleans expresses himself as still retaining the government at the request of his dear nephew Jodocus; but this appears to be a mistake, since Jodocus was elected emperor in 1410, and died six months after, before his election could be confirmed. He was succeeded by his brother Procopius.

28. Rupert, or Robert, elector palatine (see the genealogy, p. 12.) was elected emperor upon the deposition of Wenceslaus king of Bohemia.

29. John Galeas Visconti, first duke of Milan, father of Valentina duchess of Orleans. During the reign of Wenceslaus, he had made the most violent aggressions on the free and imperial states of Lombardy, which it was the first object of the new emperor to chastise. The battle or skirmish here alluded to was fought near the walls of Brescia.

30. This chapter presents a most extraordinary confusion of dates and events. The conclusion can refer only to the battle of Shrewsbury, which took place more than two years afterwards,—and is again mentioned in its proper place, chap. XV.: besides which, the facts are misrepresented. Monstrelet should have said, ‘The lord Thomas Percy (earl of Worcester) was beheaded after the battle, and his nephew Henry slain on the field.’ The year 1401 was, in fact, distinguished only by the war in Wales against Owen Glendower, in which Harry Percy commanded for, not against, the king. The Percies did not rebel till the year 1403.

31. This John de Werchin, seneschal of Hainault, was connected by marriage with the house of Luxembourg St Pol.

32. Enguerrand VII. lord of Coucy and count of Soissons, died a prisoner in Turkey, as related by Froissart. Mary, his daughter and co-heiress, sold her possessions, and this castle of Coucy among the rest, to Louis duke of Orleans. His other daughters were, Mary wife of Robert Vere, duke of Ireland (the ill-fated favourite of Richard II.) and Isabel, married to Philip count of Nevers, youngest son of the duke of Burgundy.

33. Spinguchen. Q. Speenham?

34. Jodocus marquis of Moravia and Brandenburg, cousin-german to the emperor Wenceslaus, appears to be here meant. See the following

35. Charles the bold, married to a daughter of Robert of Bavaria, elector palatine, and afterwards emperor.

36. Adolphus II. duke of Cleves, married Mary daughter of the duke of Burgundy.

37. This seems to allude, in an enigmatical manner, to the charge of sorcery and witchcraft against the person of the king of France, of which the duke’s enemies accused him, as we find afterwards in doctor Petit’s justification of the duke of Burgundy.

38. This was the half-sister of Richard, and daughter of the countess of Kent, by her second husband, Thomas Holland, knight of the Garter, and earl of Kent in right of his wife. She had been before separated from her first husband, William Montague, earl of Salisbury. Her third husband was Edward prince of Wales, by whom she had king Richard.

39. Edward duke of Aumerle and earl of Rutland, son to Edmund duke of York, and cousin-german both to Richard II. and Henry IV. The reason of the personal hatred of the count de St Pol against this prince appears to be his having deserted and betrayed the conspirators at Windsor. The discovery of that plot probably hastened the death of Richard II.

40. James II. count de la Marche, great chamberlain of France, succeeded to his father John in 1393, died 1438.

41. Louis, count of Vendôme (the inheritance of his mother) second son of John count de la Marche, died 1446.

42. John, lord of Clarency, third son of John count de la Marche, died 1458.

43. Sallemue. Q. Saltash?

44. Chastel, the name of a noble house in Brittany. Tanneguy, so often mentioned hereafter, was of the same family.

45. Morlens. Q. Morlaix?

46. Chastel-Pol. Q. St Pol de Leon?

47. At the entrance of Brest harbour.

48. In 1383, he was appointed to the office of grand treasurer.

49. He is said, during his exile, to have signalized himself, like a true knight, in combating the Saracens, of whom he brought back to France so many prisoners that he constructed his magnificent castle of Seignelay without the aid of other labourers.—Paradin, cited by Moreri, Art. ‘Savoisy.’

50. William de Tignonville. The event here recorded happened in 1408. After the bodies were taken down from the gibbets, he was compelled to kiss them on the mouths.

MORERI.

51. John, king of Arragon, was killed in 1395 by a fall from his horse while hunting. By Matthea of Armagnac, his queen, he had two daughters, of whom the eldest was married to Matthew viscount de Chateaubon and count of Foix, who claimed the crown in right of his wife, and invaded Arragon in support of his pretensions. But the principal nobility having, in the mean time, called over Martin king of Sicily, brother of John, to be his successor, a bloody war ensued, which terminated only with the death of the count de Foix. After that event (which took place in 1398), Martin remained in peaceable possession of the crown. The right to the crown, both by the general law of succession and by virtue of the marriage-contract, appears to have been in the countess of Foix; but the states of the kingdom here, as in some other instances, seem to have assumed a controuling, elective power. This authority, probably inherent in the constitution, was more signally exercised in the death of Martin without issue in the year 1410.

52. Jean Carmen. Q. Carmaing?

53. Pierre de Monstarde. Q. Peter de Moncada, the name of an illustrious family in Arragon?

54. Duke de Caudie. Q. Duke of Gandia? Don Alphonso, a prince of the house of Arragon, was honoured with that title by Martin on his accession.

55. De Sardonne. Q. Count of Cardona? He was one of the deputies from the states to don Martin, on the death of John.

56. D’Aviemie. Q. Count of Ampurias? This nobleman was another descendant of the house of Arragon. He espoused at first the party of Foix, but soon reconciled himself to Martin.

57. Before called Peter.

58. Of this invasion, Stowe gives the following brief account: ‘The lord of Cassels, in Brytaine, arrived at Blackepoole, two miles out of Dartmouth, with a great navy, where, of the rustical people whom he ever despised, he was slaine.’

59. John de Hangest, lord de Huqueville.

60. Owen Glendower.

61. Linorquie. Q. Glamorgan?

62. Round Table. Q. Caerleon in Monmouthshire, one of Arthur’s seats?

63. Regnault de Trie, lord of Fontenay, was admiral of France on the death of the lord de Vienne, killed at Nicopolis. He resigned, in 1405, in favour of Peter de Breban, lord of Landreville, surnamed Clugnet, and hereafter mentioned, but falsely, by the name of Clugnet de Brabant.

64. This famous battle was fought at Angora in Galatia.

65. Charles III. succeeded his father, Charles the bad, in 1386.

66. This county descended to him from his great grandfather Louis, count of Evreux, son to Philip the bold, king of France. Philip, son of Louis, became king of Navarre in right of his wife Jane, daughter of Louis Hutin. He was father of Charles the bad.

67. Mary of France, daughter of king John, married Robert duke of Bar, by whom she had issue Edward duke of Bar and Louis cardinal, hereafter mentioned, besides other children.

68. Rather aunt. John III. duke of Brabant, dying in the year 1335, without male issue, left his dominions to his eldest daughter Joan, who married Wenceslaus duke of Luxembourg, and survived her husband many years, dying, at a very advanced age, in the year 1406. She is the princess here mentioned. Margaret, youngest daughter of John III. married Louis de Male, earl of Flanders; and her only daughter Margaret (consequently niece of Joan duchess of Brabant) brought the inheritance of Flanders to Philip duke of Burgundy.

69. The heiress of Flanders, mentioned in the preceding page.

70. Catherine, married to Leopold the proud, duke of Austria.

71. Margaret, married to William of Bavaria, (VI. of the name), count of Holland and Hainault.

72. Mary, married to Amadeus VIII. first duke of Savoy, afterwards pope by the name of Felix V.

73. Limbourg, on the death of its last duke, Henry, about 1300, was purchased, by John duke of Brabant, of Adolph count of Mons. Reginald duke of Gueldres claimed the succession; and his pretensions gave rise to the bloody war detailed by Froissart, which ended with the battle of Wareng.

74. John, son of Louis the good, duke of Bourbon, so celebrated in the Chronicle of Froissart. The family was descended from Robert count of Clermont, son of St Louis who married the heiress of the ancient lords of the Bourbonnois. Louis, son of Robert, had two sons, Peter, the eldest (father of duke Louis the good) through whom descended the first line of Bourbon and that of Montpensier, both of which became extinct in the persons of Susannah, duchess of Bourbon, and Charles count of Montpensier her husband, the famous constable of France killed at the siege of Rome. James, the younger son of Louis I. was founder of the second line of Bourbon. John, count of la Marche, his son, became count of Vendôme in right of his wife, the heiress of that county. Anthony, fifth in lineal descent, became king of Navarre, in right also of his wife, and is well known as father of king Henry IV.

75. Matthew count of Foix, the unsuccessful competitor for the crown of Arragon, was succeeded by his sister Isabel, the wife of Archambaud de Greilly, son of the famous captal de Buche, who became count of Foix in her right. His son John, here called viscount de Châteaubon, was his successor.

76. Charles d’Albret, count of Dreux and viscount of Tartas, constable, lineal ancestor of John king of Navarre.

77. Carlefin. Q. Carlat?

78. Duke Albert had four other children not mentioned in this history, viz. Albert, who died young,—Catherine, married to the duke of Gueldres,—Anne, wife of the emperor Wenceslaus,—and Jane, married to Albert IV. duke of Austria, surnamed the Wonder of the World.

79. Peter de Luna, antipope of Avignon, elected after the death of Clement VII.

80. Hollingshed says, sir Philip Hall was governor of the castle of Mercq, ‘having with him four score archers and four-and-twenty other soldiers.’

The troops from Calais were commanded by sir Richard Aston, knight, ‘lieutenant of the english pale for the earl of Somerset, captain-general of those marches.’

81. Hangest, a noble family in Picardy. Rogues de Hangest was grand pannetier and maréschal of France in 1352. His son, John Rabache, died a hostage in London. John de Hangest, grandson of Rogues, is here meant. He was chamberlain to the king and much esteemed at court. His son Miles was the last male of the family.

82. Aynard de Clermont en Dauphinè married Jane de Maingret, heiress of Dampierre, about the middle of the 14th century. Probably their son was the lord de Dampierre here mentioned.

83. Andrew lord de Rambures was governor of Gravelines. His son, David, is the person here mentioned. He was appointed grand master of the cross-bows, and fell at the battle of Agincourt with three of his sons. Andrew II. his only surviving son, continued the line of Rambures.

84. John de Craon, lord of Montbazon and Sainte Maure, grand echanson de France, killed at Agincourt.

85. Antoine de Vergy, count de Dammartin, maréschal of France in 1421.

86. Hollingshed says, this expedition was commanded by king Henry’s son, the lord Thomas of Lancaster, and the earl of Kent. He doubts the earl of Pembroke bring slain, for he writes, ‘the person whom the Flemings called earl of Pembroke.’ He also differs, as to the return of the English, from Monstrelet, and describes a sea-fight with four genoese carracks, when the victory was gained by the English, who afterward sailed to the coast of France, and burnt thirty-six towns in Normandy, &c.

87. John lord of Croy, Renty, &c. counsellor and chamberlain to the two dukes of Burgundy, Philip and John, afterwards grand butler of France, killed at Agincourt.

88. John de Montagu, vidame du Laonnois, lord of Montagu en Laye, counsellor and chamberlain of the king, and grand master of the household. He was the son of Gerard de Montagu, a bourgeois of Paris, secretary to king Charles V. Through his great interest at court, his two brothers were presented, one to the bishoprick of Paris, the other to the archbishoprick of Sens and office of chancellor.

89. This term may excite a smile. Monstrelet was a staunch Burgundian.

90. He styles himself count of Rethel, because, as duke of Limbourg, he was a member of the empire, and owed the king no homage.

91. Brother of William count of Hainault.

92. Philip the bold, king of France, gave the county of Alençon to his son Charles count of Valois, father of Philip VI. and of Charles II. count of Alençon, who was succeeded by his son Peter, the third count, who, dying in 1404, left it to his son, John, last count and first duke of Alençon, here mentioned. Alençon reverted to the crown on the death of Charles III. the last duke, in 1525.

93. Louis II. son of Louis duke of Anjou and king of Naples, brother to king Charles V. whose expedition is recorded by Froissart.

94. The devices of the two parties are different in Pontus Heuterus. (Rerum Burgundicarum, l. 3.) According to him, the Orleans-men bore on their lances a white pennon, with the inscription, Jacio Aleam; and the Burgundians set up in opposition pennons of purple, inscribed Accipio conditionem.

95. William II. count of Namur.

96. Monstrelet is mistaken as to the names of the english ambassadors. The first embassy took place the 22d March 1406, and the ambassadors were the bishop of Winchester, Thomas lord de Camoys, John Norbury, esquire, and master John Cateryk, treasurer of the cathedral of Lincoln.

A second credential letter is given to the bishop of Winchester alone, of the same date. Another credential is given to the same prelate, bearing similar date, to contract a marriage with the eldest or any other daughter of the king of France, and Henry prince of Wales.

See the Fœdera, anno 1406.

97. This is a mistake. His true name was Peter de Breban, surnamed le Clugnet, lord of Landreville.

98. Mary, daughter of William I. count of Namur, married first to Guy de Châtillon, count of Blois, and secondly to this admiral de Breban. On the deaths of both her brothers (William II. in 1418, and John III. in 1428) she became countess of Namur in her own right; and after her it came to Philip the good, duke of Burgundy, as a reversion to the earldom of Flanders.

99. Frederick, second son of John duke of