CHAPTER XI.

Wherein Captain Galligasken describes the Battle of Belmont, and further illustrates the military Qualities of the illustrious Soldier, as exhibited in that fierce Fight.

With such a man as Smith at Paducah, placed there, and kept there, by General Grant, the outlets of those great rivers, the Tennessee and the Cumberland, which led down into the very heart of the Rebellion, were safe. We looked to Grant—we, within the narrow sphere he then occupied—for another movement, for some brilliant and well-conceived operation, which would gladden the hearts and strengthen the arms of the men of the loyal cause; but we looked in vain, for he was not the commander of a department, and was held back by General Fremont. But Grant was busy, and not a moment of his precious time was lost, however it may have been turned aside from its highest usefulness. The hardy and enthusiastic volunteers from the North-west were poured in upon him until he had about twenty thousand. He employed himself in perfecting their organization and improving their discipline.

Columbus, which had been fortified and held by Polk and Pillow, was every day increasing its strength and importance. It had closed the Mississippi, and every point in Grant's district was continually menaced by it. He desired to "wipe it out," and applied to Fremont for permission to do so, declaring that, with a little addition to his present force, he would take the place. His application was not even noticed, and the rebels were permitted to strengthen their works, and afford all the aid they could to the turbulent hosts in Missouri.

In the mean time the rebel General Price had captured Lexington, but abandoned his prize at the approach of Fremont, and retreated to the south-western part of the state, where he remained, confronted by a small force of national troops, gathering strength for another hostile movement towards the north. Polk, who was in command of Columbus, occasionally sent troops over the river to Belmont, on the opposite bank, from which they marched to re-enforce Price. The safety of the Union army before him required that this channel of communication should be closed, or at least that the enemy in Missouri should be prevented for a time from receiving further assistance.

General Grant was therefore ordered to make a movement which should threaten Columbus, and thus compel Polk to retain his force. Accordingly, he sent Colonel Oglesby towards the point he was to menace, and also directed General Smith at Paducah to march towards Columbus, and demonstrate in the rear of that place. The point to be gained was simply to prevent reënforcements from being sent over the river, for Grant was prohibited from making an attack upon the threatened point.

Belmont was partially fortified. It was a camp for rebel troops, from which they could conveniently be sent to cooperate with Price or Jeff. Thompson, and a depot of supplies gathered up in Missouri and Arkansas, where they could be readily sent over to Columbus. On the evening of November 6, Grant started down the river with a fleet of steamers, under the convoy of two gunboats, to demonstrate on a larger scale against the enemy's stronghold. He had with him a force of thirty-one hundred men, comprising five regiments of infantry, two squadrons of cavalry, and a section of artillery. The movement was not intended as an attack, even upon Belmont, at the beginning. His troops were exceedingly raw, some of them having received their arms only two days before.

The fleet continued down the river about ten miles, and Grant made a feint of landing on the Kentucky side, remaining at the shore till the next morning, to give color to the idea that, with Smith, he intended to attack Columbus. But during the night he ascertained that Polk was crossing large bodies of troops to Belmont, with the evident intention of pursuing Oglesby. Then the intrepid general decided to "clean out" the camp at Belmont. This was literally what he intended to do, and as every man's success ought to be measured by his intentions, it is very important that this fact should be fully comprehended. It is absurd to suppose that a military man of Grant's experience proposed to take and hold the place. He had every reason to believe the enemy had double his force, and he knew that they were well provided with steamers and gunboats, and could send over reenforcements rapidly; and he was also aware that Belmont was covered by the guns of Columbus. Against this odds, and under these circumstances, he could not for a moment have entertained the idea of securing a permanent advantage. He contemplated only a bold dash, which was sufficient to accomplish the object of the expedition.

The little army was landed at Hunter's Point, three miles above the rebel works, and just out of the range of the Columbus batteries. The line was formed, and, with Grant in the advance with the skirmishers, moved forward. It soon encountered the enemy, and drove them before it. The action waxed warmer and warmer as the lines of national troops advanced, and the contest became very severe. Grant still kept in front, animating the soldiers by his heroic example, in utter contempt of anything like danger. His horse was killed under him, and he was in peril from first to last; but his gallant behavior stimulated the civilian colonels under him, and they stood up squarely to the work before them. Thus led, the raw soldiers from Illinois behaved like veterans, and fought with the utmost desperation. The contest continued for four hours, at the end of which time the Union troops had driven the rebels foot by foot to their works; and then, charging through the abatis which surrounded the fortifications, forced the beaten foe to the river. Several hundred prisoners and all the rebel guns were captured, and the camp broken up.

Grant had reached his objective point, and his success was thorough and complete. He had accomplished all he proposed, and it only remained for him to retire from the field, which was of course as much a part of his original intention as was the attack. As the hour of prosperity is often the most dangerous, so was the moment of victory the most perilous to these gallant troops. Their success seemed to intoxicate them, and instead of pursuing their advantage upon the rebel force, sheltering themselves beneath the bluff of the river, they went about plundering the deserted camp. Their colonels, no better disciplined, indulged their vanity in making Union speeches.

General Grant discovered that the enemy was sending steamer loads of troops across the river, to a point above the camp, to intercept his retreat; and he was anxious to get back to his transports before they arrived. He attempted to form his lines again, but the men were too much disorganized to heed orders. The general then directed his staff-officers to set fire to the camp, in order to check the plunder. The smoke attracted the attention of the rebels at Columbus, who opened fire upon the Unionists. Shot and shell brought them to a sense of their duty; the line was formed, and they marched towards the steamers, three miles distant.

The defeated rebels, under the bank of the river, having been reënforced by the arrival of three regiments from Columbus, marched to a point which enabled them to intercept the victorious army. An officer, on discovering the fact, dashed furiously up to the cool commander, and in a highly-excited tone cried, "We are surrounded!"

"Well, if that is so, we must cut our way out, as we cut our way in," replied Grant, apparently unmoved even by this tremendous circumstance.

His troops were brave men, but such a disaster as being surrounded suggested to their inexperience only the alternative of surrender, and, under many commanders, such a result must have been inevitable. What paralyzes the soldier often produces the same effect upon the leader; but Grant was not "demoralized." No apparent reverses could exhaust his unconquerable pluck; he never despaired, and worked up a situation out of which another could make nothing but defeat, until he brought forth victory.

"We have whipped them once, and I think we can do it again," added Grant, in the midst of the confusion which the unpleasant prospect caused.

The troops discovered that Grant had no idea of surrendering, and they gathered themselves up for a fresh onslaught. The confusion was overcome, and the little army charged the enemy, who fought less vigorously than earlier in the day, and were again forced behind the bank of the river. But, as fresh troops were continually arriving from Columbus, there was no time to be wasted, and Grant pressed on for his transports. There was no unseemly haste, certainly nothing like a rout, or even a defeat. Everything was done in as orderly a manner as possible with undisciplined troops.

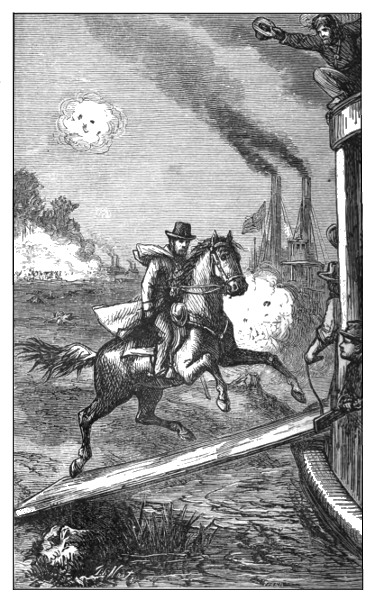

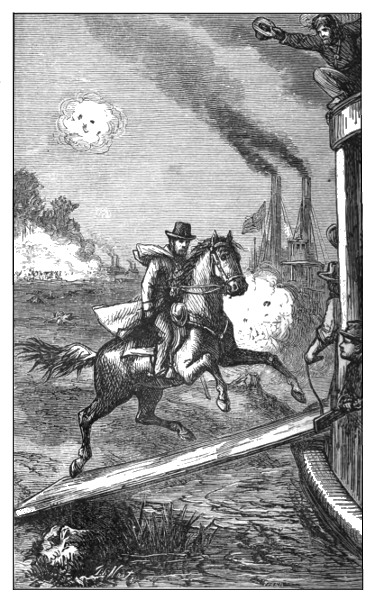

Grant's Escape.—.

Grant superintended the execution of his own orders in the embarkation of his force; and, when most of them were on board of the steamers, he sent out a party to pick up the wounded. In the morning he had posted a reserve in a suitable place for the protection of the fleet, and as soon as the main body were secure on the decks of the transports, Grant, attended by a single member of his staff, rode out to withdraw this force. This guard, ignorant of the requirement of good discipline, had withdrawn themselves, and the general found himself uncovered in the presence of the advancing foe. Riding up on a hillock, he found himself confronting the whole rebel force, now again increased by fresh additions from the other side of the river. It was a time for an ordinary man to put spurs to his steed; but Grant had an utter contempt for danger. He stood still for a moment to examine the situation, during which he was a shining mark for rebel sharp-shooters. He wore a private's overcoat, the day being damp and chilly; and to this circumstance alone can his miraculous escape be attributed.

He was looking for the party he had sent out in search of the wounded, and realized that they had been cut off by the foe. Turning his horse, he rode slowly back to the landing, so as not to excite the attention of his uncomfortable neighbors, who were pouring a galling fire into the transports. The steamers suffered so much from this destructive hail of bullets, that they had cast off their fasts, and pushed away from the bank, leaving the general behind in the midst of the foe. Seeing how the thing was going, Grant put spurs to his horse, forcing the steed on his haunches down the bank, just as one of the steamers was swinging off from the shore. A plank was thrown out for him, up which he trotted his horse, in the midst of a storm of rebel bullets.

The field being clear of national troops, the gun boats opened a fierce fire upon the rebel ranks, now within fifty or sixty yards of the shore, mowing them down with grape and canister in the most fearful slaughter. The fire of the rebels was fortunately too high to inflict any serious injury on the troops in the transports, and by five in the afternoon they were out of range.

The next day Grant met, under a flag of truce, an old classmate from West Point, then serving on General Polk's staff. He related his personal experience at Belmont, stating that he had encountered the rebel line when alone. The rebel officer expressed his surprise.

"Was that you?" exclaimed he. "We saw you. General Polk pointed you out as a Yankee, and called upon the men to test their aim upon you; but they were too busy in trying their skill upon the transports to heed the suggestion."

I point with admiration to the conduct of General Grant during that entire day. As an example of coolness and courage, he stands unsurpassed, and even unrivalled. It was thrilling to behold him, in the midst of the trials and discouragements of that hard-fought field, the life and the soul of the whole affair. He was the only trained soldier on the field, for even General McClernand, who was daring enough to have had three horses shot under him, had no actual experience of battle. His men, and especially his officers, were undisciplined, and the whole affair rested upon his shoulders. But the brave fellows followed his example, and the victory was made sure.

The material results of the battle were one hundred and seventy-five prisoners, two guns carried off and four spiked on the field, and the total destruction of the enemy's camp.

Of the force engaged, Grant had thirty-one hundred and fourteen men, according to his official report. General Polk declared that, at the beginning of the battle, Pillow had five regiments, a battery, and a squadron of cavalry; and that five more regiments were sent across the river during the fight. The rebel force, therefore, must have been double that of the Unionists; and probably the disparity was still greater.

My friend Mr. Pollard, with his usual cheerful assumption, called the battle of Belmont a Confederate victory! Or, stating it a little more mildly, a defeat in the beginning changed in the end to an overwhelming victory! Did this amiable rebel ever hear of an army defeated by an "overwhelming victory," carrying off their captured guns and prisoners, embarking leisurely in their steamers, and retiring while the victors were being mowed down in swaths? Grant lost four hundred and eighty-five men in killed, wounded, and missing; while Mr. Pollard demolishes his own "overwhelming victory" by acknowledging a rebel loss of six hundred and forty-two, which was probably below the actual number.

The moral results of the battle, which cannot be estimated in captured guns and prisoners, were even more satisfactory. Belmont, as settling a question of prestige, was the Bunker Hill of the Western soldiers. It gave them confidence in themselves, and prepared the way for Donelson and Shiloh. It prevented the forces of Jeff Thompson and Price from being augmented.

The unmilitary conduct of some of the colonels, gallantly as they fought, exposed them to merited rebuke. It is said that Grant himself expected to be deprived of his command for fighting this battle, and for not effecting his retreat more promptly, having been delayed, as I have shown, by the want of proper support from these commanders of regiments, who did not control, or attempt to control, the excesses of the men. One of them, fearful that the same fate was in store for him, waited upon Grant to ascertain the prospect. He obtained no satisfaction, for the general thought the lesson ought to work in his mind.

"Colonel —— is afraid I will report his bad conduct," said Grant to one of his friends, when the repentant and anxious officer had departed.

"Why don't you do it?" demanded the other. "He and the other colonels are to blame for their disobedience, which had nearly involved you in a disaster."

"These officers had never been under fire," replied the magnanimous hero. "They did not understand how serious an affair it was, and they will never forget the lesson they learned. I can judge from their conduct in the action that they are made of the right stuff. It is better that I should lose my position, if it must be, than that the country should lose the services of five such gallant officers when good men are scarce."

Grant did not lose his command; and the future justified the belief of Grant, for three of the five colonels won an enviable distinction in subsequent battles.

That was Grant! It was the imperilled nation, and not his own glory, for which he was fighting.