CHAPTER XXX.

Wherein Captain Galligasken follows the illustrious Soldier in his Career after the War, relates several Anecdotes of him, and respectfully invites the whole World to match him.

The war was ended, and far above every other man in the country, civilian or soldier, stood General Grant. In this sublime attitude he was still the same simple-hearted, plain, and unostentatious man. The people, full of admiration and gratitude, rendered every honor to the illustrious soldier which ingenuity could devise. Presents of every description poured in upon him. Two valuable houses, richly furnished, a library, and princely sums of money were given to him, and gratefully received, as tokens of the people's regard. He made several tours of pleasure and business, in which he was everywhere received with the most tremendous demonstrations of applause. There could be no mistaking his hold upon the people. They loved, admired, respected him. But in the midst of these splendid ovations, he was still modest, self-possessed, and dignified.

In 1865 Grant visited the Senate Chamber at Washington. He paid his respects to the senators, and left the room. When he had gone, one of the Democratic members declared that a great mistake had been made in appointing Grant a lieutenant general, for there wasn't a second lieutenant in the home-guard of his state who did not "cut a bigger swell" than the man who had just left their presence! When he was regarded as an available candidate for the presidency during the war, he was approached on the subject by a zealous partisan. He declared that there was only one political office which he desired. When the war was over, he wanted to be elected mayor of Galena! If successful, he intended to see to it that the sidewalk between his house and the depot was put in better order. In one of his excursions in 1865, he visited his former home at Galena. A magnificent reception welcomed him. Triumphal arches greeted him in the streets, in which were blazoned the victories he had won. In that which contained his house and the sidewalk he condemned was one bearing the inscription, "General, the sidewalk is built."

At Georgetown, where his childhood had been spent, and in whose streets he had first smelt gunpowder as a baby, the whole town turned out to see and to greet him with the homage due to the great conqueror. Here he made one of his longest speeches, amounting to something like ten lines! In Philadelphia, New York, and Boston, he was received as no man ever had been before. At West Point, whither he had gone to pay his grateful respects to his alma mater, Lieutenant General Scott, his old commander in Mexico, presented him a copy of "Scott's Memoirs," inscribed, "From the oldest to the greatest General." If Scott's opinion, as a military man, is worth anything to the sceptic, here was his written indorsement of the preëminence of Grant.

Grant made no speeches. In this respect he has been an enigma to the American people. He was a reticent man, in the fullest sense of the word. For my own part, I should as soon think of condemning Abraham Lincoln because he could not, or did not, turn back somersets on a tight rope, as to complain of Grant because he could not, or did not, make speeches. In this respect he does not differ from hundreds of other great men. Washington and Jefferson were very indifferent speech-makers. Napoleon wrote startling bulletins, but never distinguished himself as an orator. Grant's congratulatory orders are full of fire, and, better, full of sound common sense. His reports are replete with wisdom simply expressed, and they are models of compact narration.

I wish to go a step further. I fully believe that Grant's reticence is one of the elements of his greatness. It is impossible for me to think of him as a successful commander, if he had been a brawler, or even a great talker. Most emphatically was his silence, his reticence, "golden." I can point to not less than three generals, high in position, who might have been successful if they had possessed a talent for holding their tongues. But Grant has always said enough, and, better still, done enough, to enable the people to ascertain his opinions on great subjects before the country. His position during the Rebellion, in regard to slavery, negro soldiers, and the general conduct of the war, was not concealed. The people knew just how he stood. His orders are open, unreserved; and no man's record more thoroughly commits him to the people's policy than that of Grant. He was one of the first to give effective aid to the government, in enlisting and organizing negro troops—a subject so trying to the nerves of many of the old army officers, that they were either dumb, or arrayed in virtual opposition to the national policy.

During the troubles between the president and Congress, Grant made no speeches, published no opinions on the disputed questions. The president is the constitutional commander-in-chief of the army, and in his purely military capacity, it would have been improper and indelicate for Grant to meddle with the controversy. But who doubted his sentiments? Congress practically gave him the execution of its plan of reconstruction. It made laws, and depended upon him to carry them out. It is enough to know that Congress confided implicitly in him, and that he drew upon himself the hostility, and even the hatred, of the president, by his manly and straight-forward course.

Grant's reticence was one of the elements of his success, I repeat. He kept his plans to himself. Even his subordinate generals were not often permitted to know them in advance of their execution. One of them visited the lieutenant general, intent upon ascertaining the programme of the chief.

"What are your plans, general, for the conduct of the campaign?" asked the inquirer, not doubting that he had a perfect right to know.

"General, I have a fine horse out here; I want you to go and look at him," replied Grant, leading the way out of the tent.

The inquirer was mortally offended at the coolness with which his question was evaded. On another occasion, the editor of a leading political journal, a young man of fine abilities, but having a rather high estimate of his personal consequence, was presented to the lieutenant general. In the course of the conversation, he attempted to draw from the silent hero some political opinion in regard to the South. Grant replied that they had some fine horses down south, and made an enemy of the politician.

In his reticence there was a purpose; but his silence, so far as speech-making is concerned, is the offspring of constitutional modesty. He is not an off-hand speaker. George Francis Train can make a speech, but Grant cannot. Andrew Johnson can talk in public, but even his best friends have had abundant reason to wish that he could not. It is a notable fact that the greatest orators have generally failed to reach the highest positions of honor and trust. Webster, Clay, and Everett, besides being great statesmen, were brilliant men in the forum; yet all of them died without occupying the seat of the president. But Grant is simply not an impromptu speaker. When the occasion requires, he reads his speech, as greater orators than he are compelled to do. Even Everett never spoke without careful preparation, and the elaborate orations he delivered were generally in type before he declaimed them. I have no fears that Grant will fall short of the expectations even of the American people in this respect, when he has been elected to the presidency; but I am equally confident that he will never become a shame and a scandal to the nation on account of his vicious and unconsidered addresses.

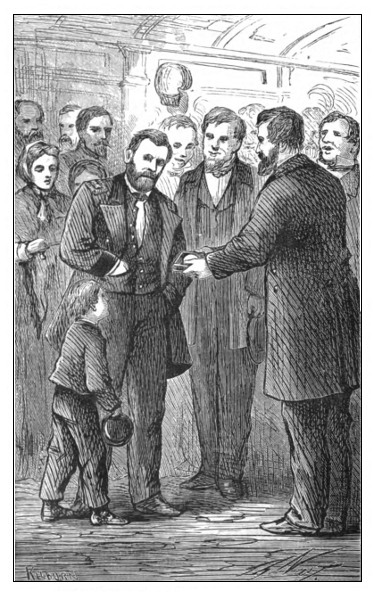

When the gold medal, which was voted by resolution of Congress to Grant, after the campaign of Chattanooga, was finished, a committee from the two houses went down to City Point in a special steamer to present the elegant testimonial of the nation's gratitude to the illustrious soldier. The members of the committee waited upon the lieutenant general, and arranged with him that the formal ceremony of the presentation should take place on board of the headquarters steamer, where ample accommodations were made for the party who were to witness the impressive scene. At the appointed time, the committee, with a few invited guests, appeared. The lieutenant general was attended by his staff, and a few other officers of the army, on duty at the post. One of the most interesting features of the occasion was the presence of General Grant's family, including his wife, his son, and daughter. The youngest of the group was Master Jesse, a bright, handsome lad of six summers, who attracted no inconsiderable degree of attention, not only from his relation to the mighty man of the nation, but on account of his personal attributes. The guests were gathered together in the cabin of the steamer where the ceremony was to take place. The spokesman of the committee stepped forward, and in a neat and appropriate address presented the medal.

General Grant's time came then, and, as usual on all similar occasions, he was greatly embarrassed. He could stand undisturbed while five hundred cannons were thundering in his ears, but he seems to have been afraid of the sound of his own voice. All present were curious to know what he would say, and how he would say it, for he had never made an impromptu speech. The general appeared to be slightly agitated as soon as the congressman's speech had been concluded. He began to fumble about his pockets, just as a school-boy does on the rostrum. He was evidently looking for something, and he could not find it. The delay became painful and awkward in the extreme, not only to the general, but to his sympathizing audience; and little Jesse, his son, seemed to suffer the most in this prolonged interval. At last his patience was exhausted, and he cried out,—

"Father, why don't you say something."—.

"Father, why don't you say something?"

A burst of applause from the assembly greeted this speech, and it was plain that Jesse had said the right word at the right time. Inheriting some of his father's military genius, he had made a demonstration which turned the attention of the company for the time from the embarrassed general, who, taking advantage of the diversion, renewed the onslaught upon his pockets, and brought forth the written paper for which he had been searching. He then read his "impromptu" speech, which was a simple expression of his thanks, set forth in solid phrase, for the distinguished honor which had been conferred upon him. The assembly were then invited to the spacious between-decks of the steamer, where a substantial collation had been prepared for them; and Jesse was not the least honored and petted of the party.

It is sometimes awkward and unpleasant for a man in public life to be unable to make a speech, but experience has demonstrated that it is often ten times more awkward and unpleasant to be able to make one; and better than any other gift can we spare in an American president that of off-hand-speech making. Grant is a thinking man, and his thought is the father of his mighty deeds. His most expressive speech was made to Sheridan: "Go in!" In the army it was the common remark of the soldiers that Grant did not say much, but he kept up a tremendous thinking. In his capacious brain there was room for all the multiplied details of a vast army. His mind contained a map of the theatre of operations, and he knew where everything and everybody was. He understood how the battle was going miles away from his position. At The Wilderness he stood under a tree with General Meade, whittling, as he was wont to do when brooding in deep thought, smoking, of course, at the same time. An aid dashed furiously up to the spot, and announced that one of the corps holding an important position in the line had broken, and been driven from the field. Meade was intensely agitated, for the event indicated nothing but disaster. Grant smoked and whittled as coolly as though there had been no hostile armies on the continent.

"Good God!" exclaimed Meade, as the details were enlarged upon by the messenger.

Still Grant whittled and thought. A minute elapsed before he spoke, in which he seemed to be consulting his mental map.

"I don't believe it," said he, at last, while the messenger of disaster was still in his presence.

The sequel proved that Grant was right, and the messenger direct from the scene was wrong. The battle had surged in upon the national line for a moment, but there was no break, no defeat, no disaster. It has been observed that Grant whittles two ways—from and towards his body. When he is maturing a plan, solving a problem involved in his operations, he whittles towards himself, as if to concentrate within him some invisible magnetism floating in the air around him. But when his mind grasps the solution of the problem, when the plan is formed, he instantly reverses the stick, and whittles from himself. Perhaps to the nation it does not make much difference which way he whittles, while it is patent to the world that he whittled down the Rebellion.

In 1866 Grant was made a full general, the office having been created especially for him. He was not a merely ornamental appendage of the government, but used a laboring oar in his lofty position. He was tender of the people's pockets, heavily drawn upon by the needs of the war. He introduced reforms into the army, largely curtailing the public expense, and exhibiting a spirit of economy which was very hopeful in the people's candidate for the presidency.

The war was ended, and with it slavery and the tyranny of one section over the other. The sword had done its work effectually, and the statesman's task of reconstruction was to be completed—a task hardly less difficult than putting down the Rebellion itself. Then commenced the unfortunate conflict between the president and Congress. The people, through their representatives, had adopted the present policy of reconstruction, sustaining it by their voices, their votes, and their influence. Grant believed in this system, and, so far as his military position would permit, gave his energies to its support. Congress, having full confidence in his integrity and his sound judgment, conferred upon him extraordinary powers. As the commander of all the armies while the South was held in military subjection, he had the power to advance or to thwart the people's policy. He maintained it with all his ability, and thus became the very life and soul of the system. Stanton, the tried and true, in the cabinet, was a check upon the president in his insane attempts to usurp the powers of the legislative branch of the government, and to thwart the expressed will of the people.

At last the president removed him, subject to the approval of Congress, under the tenure of office act, and Grant was appointed secretary of war ad interim. In the lieutenant general's letter to Stanton—his constant friend and tried supporter during the war—he takes the occasion to express his appreciation of the zeal, patriotism, firmness, and ability with which the retiring officer had ever discharged his duty as secretary of war, thus preventing any misunderstanding of his position. In a private letter to the president the general protests smartly and warmly against the removal of Stanton and of Sheridan, the latter in command of the Fifth Military District. This letter was an admirable paper, as plucky as it was cogent in its reasoning; but it had no influence upon the stubborn will of the president. As secretary of war, Grant signalized his brief term by acts of immense importance in the reduction of expenses. On the reassembling of Congress, the Senate declined to acquiesce in the removal of Stanton, and the general immediately surrendered the office to its legal incumbent. It appeared that the president had no intention of permitting the law of Congress to take its course, but designed to disobey and disregard it. He attempted to make Grant the cat's-paw of his vicious purposes; but the sterling honesty and simple integrity of the illustrious soldier carried him safely through the ordeal. From beginning to end, Grant had resisted all overtures to indorse the president's policy. In the grand "swinging round the circle" of the president, the general had the humiliation of being one of the party, and was heartily ashamed of his company; but in no other respect did he ever go with him or form one of his party. In Grant's letters to "His Excellency," the writer was fully justified before the country.

On the 20th of May, 1868, the National Republican Convention met at Chicago to nominate candidates for the presidency and vice-presidency. It was hardly necessary to nominate Grant, for he had already been fixed upon by the people for their suffrages; but the convention, on the first ballot, unanimously nominated him for this high office. The news of this great event was carried to him at once. He was unmoved by it, but asked immediately for the platform. This he carefully read, and heartily indorsed. The honor conferred upon him so unanimously was the most flattering compliment which had been bestowed upon any man since the time of Washington; but he only asked to know what principles he was expected to represent.

And now my delightful task is ended, though I shall never cease to proclaim the admiration and gratitude with which I regard the illustrious soldier on all proper occasions. As I look upon my poor work, I feel that I have failed to do justice to the sublime subject of my memoir. I cannot express all I feel. From Palo Alto to Appomattox I have followed him in his grand career, and I hold him up as a soldier confidently challenging the whole world,—

Match Him!

In the elements of magnanimity, regard for the rights of others, undeviating honor and truth, I say,—

Match Him!

As the foremost man in putting down the Rebellion, first in war and first in the hearts of his countrymen, I add,—

Match Him!

As a man, cool, resolute, and unflinching in the discharge of every duty, proving, by what he has done, what he is able to do in civil as well as in military life, I say,—

Match Him!

OLIVER OPTIC'S MAGAZINE,

The only Original American Juvenile Magazine published once a Week.

EDITED BY OLIVER OPTIC,

Who writes for no other juvenile publication—who contributes each year

Four Serial Stories,

The cost of which in book form would be $5.00—double the subscription price of the Magazine!

Each number (published every Saturday) handsomely illustrated by Thomas Nast, and other talented artists.

Among the regular contributors, besides Oliver Optic, are

SOPHIE MAY, author of "Little Prudy and Dotty Dimple Stories."

ROSA ABBOTT, author of "Jack of all Trades," &c.

MAY MANNERING, author of "The Helping-Hand Series," &c.

WIRT SIKES, author of "On the Prairies," &c.

OLIVE LOGAN, author of "Near Views of Royalty," &c.

REV. ELIJAH KELLOGG, author of "Good Old Times," &c.

Each number contains 16 pages of Original Stories, Poetry, Articles of History, Biography, Natural History, Dialogues, Recitations, Facts and Figures, Puzzles, Rebuses, &c.

Oliver Optic's Magazine contains more reading matter than any other juvenile publication, and is the Cheapest and the Best Periodical of the kind in the United States.

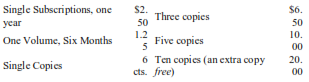

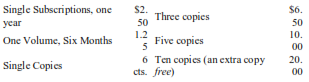

TERMS, IN ADVANCE.

Canvassers and local agents wanted in every State and town, and liberal arrangements will be made with those who apply to the Publishers.

A handsome cloth cover, with a beautiful gilt design, will be furnished for binding the numbers for the year for 50 cts. All the numbers for 1867 will be supplied for $2.25. Bound volumes, $3.50.

Any boy or girl who will write to the Publishers shall receive a specimen copy by mail free.

LEE & SHEPARD, Publishers,

149 Washington Street, Boston.

LIBRARY FOR YOUNG PEOPLE.

BY OLIVER OPTIC.

I. THE BOAT CLUB; OR, THE BUNKERS OF RIPPLETON. II. ALL ABOARD; OR, LIFE ON THE LAKE. III. LITTLE BY LITTLE; OR, THE CRUISE OF THE FLYAWAY. IV. TRY AGAIN; OR, THE TRIALS AND TRIUMPHS OF HARRY WEST. V. NOW OR NEVER; OR, THE ADVENTURES OF BOBBY BRIGHT. VI. POOR AND PROUD; OR, THE FORTUNES OF KATY REDBURN. Six volumes, put up in a neat box.

LEE & SHEPARD, Publishers.

WOODVILLE STORIES.

BY OLIVER OPTIC.

I. RICH AND HUMBLE; Or, The Mission of Bertha Grant. II. IN SCHOOL AND OUT; Or, The Conquest of Richard Grant. III. WATCH AND WAIT; Or, The Young Fugitives. IV. WORK AND WIN; Or, Noddy Newman on a Cruise. V. HOPE AND HAVE; Or, Fanny Grant among the Indians. VI. HASTE AND WASTE! Or, The Young Pilot of Lake Champlain.