CHAPTER V.

Wherein Captain Galligasken accompanies the illustrious Soldier to Mexico, and glowingly dilates upon the gallant Achievements of our Arms from Palo Alto to Monterey.

My distinguished ancestor, Sir Bernard Galligasken, was a fighting man, and was knighted for meritorious services in the loyal cause in Ireland. My respected progenitors in the New World were engaged in the French and Indian wars, and fought their way through the Revolution with credit to themselves. I inherited the military taste; but I do not mention this fact, or introduce the warlike record of my worthy ancestors, to add one jot or tittle of glory to their fame or my own, but simply to convince the reader that I have the soul to appreciate the military prowess of the illustrious soldier in the cheering light of whose brilliant deeds I am content to be ignored, eclipsed, obscured.

Grant's rank at the Military Academy consigned him to the infantry; for the best scholars of the graduating class are assigned to the more desirable arms of the service—the engineers, cavalry, artillery. But to the soldier of such transcendent abilities as those of the illustrious hero, it mattered but little to what branch he was sent. His rising star was eventually to confound all the puerile distinctions of particular arms, and to grasp them all in one comprehensive idea. He was sent to the infantry, as if to place in his path more obstacles to be overcome.

When those above him had been assigned to places in the army, all the vacancies were filled, and Grant was added as a supernumerary officer to the Fourth Infantry, with only brevet rank, there to wait till an opening was made, in those "piping times of peace," by resignation or death. His regiment was stationed in Jefferson Barracks, near St. Louis. It was dull music here for ambitious young men, full of life, and thirsting for distinction in their chosen profession; but Grant had the happiness to soften the rigor of his captivity by a pleasant episode. Frederick T. Dent, his classmate at the Military Academy, who was also assigned to the Fourth Infantry, resided in the vicinity of the barracks. The young officers were friends, and Grant was invited to the house of Dent's family, where he won the esteem and respect which have ever been accorded to him.

On the mind and heart of Miss Julia T. Dent, the sister of his professional friend, he impressed himself even more strongly than upon those of others. They were engaged; but it was not until five years later that the happy parties were married.

After a residence of a year in the vicinity of St. Louis, Grant was ordered with his regiment to Louisiana. In 1845, as the Mexican imbroglio began to assume shape and form, the Fourth was ordered to Corpus Christi to observe the movements of Mexican army concentrating on the frontier. Here he was commissioned as a full second lieutenant in the Seventh Regiment; but he was so strongly attached to the officers of the Fourth that he asked permission of the War Department to be retained in it; and his request was granted.

I am willing to confess, that, owing to my political predilections, I had not much heart in the war that was then brewing; but I was a soldier whose only duty is obedience. Grant, on the contrary, had no such scruples. His political faith fully and heartily indorsed the war, and he went into it calmly, resolutely, unflinchingly, and from a sense of duty higher even than that of soldierly obedience. I honor a man who has principles, and who has the courage to stand by them, even though he has the misfortune to disagree with me.

Corpus Christi is situated at the mouth of the Rio Nueces, between which and the Rio Grande was the disputed territory, nominally the bone of contention between the United States and Mexico. General Taylor, in command of about four thousand troops at Corpus Christi, was ordered to advance to the Rio Grande. He accordingly posted himself opposite Matamoras, having his base of supplies at Point Isabel, on the Gulf, and erected defensive works to cover his army. Ampudia and Arista, the Mexican commanders, signified that the advance of General Taylor into the disputed territory was an act of war, and that hostilities would be commenced.

Unfortunately for the Mexicans, they were commenced, and a body of dragoons under Captain Thorn ton was surprised by an overwhelming force of the enemy, and all of them killed, wounded, or captured. Our blood was up then, and we had no disposition to discuss any fine political points. All my scruples vanished, for the Mexicans had taken the initiative in the conflict, and struck down American soldiers. Their army crossed the Rio Grande, and Taylor, suspecting that Ampudia intended to attack his base of supplies, hastened to the relief of Point Isabel. Having reënforced the garrison, and assured himself of its ability to hold the place, he prepared to return to Fort Brown.

During his absence the Mexicans crossed the river again, and attacked the fort. General Taylor started early in the morning, admonished by the sound of the guns at Fort Brown that assistance was needed there. Lieutenant Grant was in the column, with his regiment. At noon we came in sight of the Mexicans drawn up in order of battle at Palo Alto. General Taylor immediately formed his line for the conflict, and for the first time in thirty-one years an American army was drawn up before a civilized foe. Lieutenant Grant was there—in the first battle of the last half century, as he was in the last one.

Taylor formed his line half a mile from the enemy, and the battle was fought mainly with artillery. Night gathered over the combatants in the same relative position. While the Mexicans had been fearfully slaughtered by the weight and range of the American guns, the loss on our side was insignificant in comparison with theirs. The enemy retired in the darkness, and we encamped on the field of battle.

Compared with the mighty actions of the late Rebellion, or even with those which followed it in the Mexican war, Palo Alto was a trivial affair, and I dwell upon it only as the occasion in which the illustrious soldier first drew his sword in actual conflict, in which he was first under the fire of an enemy. This was his baptismal battle, and there is no difficulty in believing that he behaved like a true soldier.

We slept upon the field, as we have slept upon many a field since, but only to awake to another and fiercer battle the next day. The enemy had taken up a strong position near Resaca de la Palma, three miles from Fort Brown. Whatever may be said of the Mexicans, judged by the measure of their success in the war of 1846, they were by no means a contemptible foe. They were not deficient in military science, and they stood their ground bravely, as the vast numbers of them slain in the various battles fully attest. At Resaca they were well posted in a ravine, with their flanks protected by an impenetrable jungle of scrub oaks. The battle opened with artillery, but the enthusiasm of both sides would not permit it to be continued at long range, and infantry and cavalry made some handsome charges. The Mexicans fought with dogged courage; but, in spite of this, and of the fact that they were three to our one, they were utterly defeated and routed.

The Mexican artillery was handled by General La Vega, a brave and skilful fellow, and did us much mischief. Taylor ordered Captain May, of the dragoons, to charge upon this battery, which was so gallantly done that the feat has passed into history. He was supported by the infantry, and the entire Mexican line was shattered by the onslaught. The demoralized foe fled in terror, leaving their guns and ammunition on the field, a prey to our conquering arms. La Vega, who had no talent for running away, was taken prisoner. When the night of the second battle-day closed upon the scene, not a single Mexican soldier was to be found on the east side of the Rio Grande.

General Taylor fought his battles thoroughly, and in this school of conflict Lieutenant Grant took his first lessons in actual warfare. His quaint criticism that the army of the Potomac "did not fight its battles through" conveys a vivid impression of his views on this important subject. After blood and treasure have been freely expended to procure a military success, nothing can excuse the commander from following out the results of victory to the utmost extent within his means. This was the practice of "Old Rough and Ready" in the Mexican war. He "fought his battles through," as Resaca, Monterey, and Buena Vista fully testify, thus making a wise and economical use of the resources intrusted to his keeping. Grant is a greater general than Taylor ever was, and it would not be respectful to say that he followed the example of the worthy veteran; but the experience of this period doubtless assisted in the preparation of the man for the gigantic work he was to accomplish eighteen years after.

Three months later in the year the army of General Taylor crossed the Rio Grande, and marched upon Monterey. On the 20th of September he appeared before the city with an army of six thousand men, to attack a position strong in its natural and artificial defences, and garrisoned by ten thousand troops. The conditions of successful warfare, as usually recognized by prudent commanders, were nearly reversed against the American army. Instead of having two or three to one of the garrison in force, they were nearly outnumbered in this numerical ratio. But the attack was promptly commenced, not by the slow and tedious process of regular siege operations, but by a direct assault, without wasting a single day. The battle opened on the morning following the arrival of the troops, and continued with unabated spirit during the day. Several fortified heights were carried before night, and the soldiers rested only to renew the assault the next day.

The Bishop's Palace, a strongly-fortified position in the rear of the town, and the last to yield, was gallantly carried by the force under the brave General Worth. On the third day of the fight the lower city was stormed with the most tremendous fury, the troops burrowing through the stone walls of the houses in their progress, and the defenders of the place were all driven within the citadel of the town before night again settled down upon the unequal fight. Penned in by their furious assailants, the Mexicans had no hope in continuing the resistance after the misfortunes which overtook them. Ampudia, the general in command of the city, submitted a proposition for terms which resulted in the surrender and evacuation of the town.

Thus, in three days, Monterey, a city so strong in position, and so well defended that its commander might have confidently defied a besieging army of double the force of that which sat down before its walls, was carried by repeated assaults. This was another of the training fields of Lieutenant Grant. The walls of the houses within the city were strongly built, affording ample defensive positions from which the Mexican soldiers could safely annoy the Americans. From the windows they fired down upon their assailants, disputing the possession of each dwelling with the most dogged tenacity.

In the midst of this irregular strife, while the foe in the windows were remorselessly shooting down the daring soldiers in the streets below, the ammunition of the brigade to which Lieutenant Grant was attached was nearly exhausted. It was an unpleasant position to be in, without powder and ball to keep the enemy at bay; and it was therefore necessary to send for a fresh supply, which could only be obtained by traversing a distance of four miles. But who should be the messenger to ride or walk beneath those death-dealing muskets in the windows, which were showering storms of bullets at every blue-coat which appeared in the streets below? The service was so fraught with peril, if not with certain death, that the general in command was not willing to issue a peremptory order for any one to undertake the mission. He called for a volunteer.

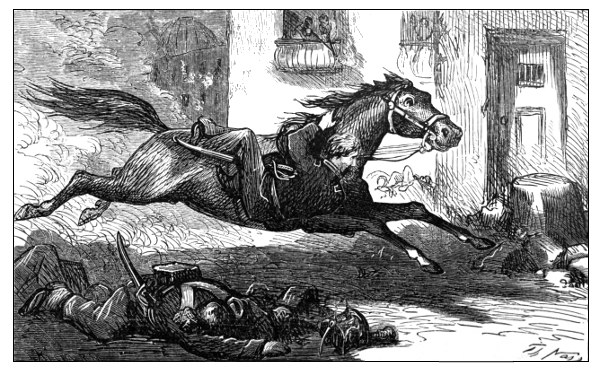

It is hardly necessary to say that, while the brigade contained a Grant, a volunteer for any desperate service would not be wanting. The lieutenant stepped forward, and was despatched on the important errand upon which nothing less than the safety of the command depended, without considering the ultimate success of the movement in progress. Grant was a bold rider, and full of expedients. He had been among the Indians of the western country, and was willing in this emergency to profit by one of their feats of horsemanship. Mounting a spirited horse, he attached one of his feet to the back of the saddle, grasping the animal's mane with the other, and permitting himself to hang down by the horse's flanks, so that his body shielded the intrepid equestrian from the bullets of the foe, who occupied the windows of only one side of the street. Hanging to his steed in this perilous attitude, he dashed off on his errand, at the highest speed of his charger, passing in safety through the destructive fire. He succeeded in bringing in a load of ammunition, guarded by a sufficient escort to insure its safety.

The capture of Monterey was a splendid feat of our arms, however it may have been cast into the shadow by the subsequent achievements of our army in Mexico. History presents a record of but few parallel victories, obtained in such a brief period, against all the disadvantages of the enemy's strong position, and with such a great disparity of numbers. The result was not because the Mexicans did not fight bravely and persistently, for they held their ground while the dead and wounded were piled high around them. The skilful officers and the trained soldiers of warlike France, exulting in her military prowess, won no such fields as Monterey and Buena Vista. While seven thousand of the Mexican soldiers in the city were regulars, Taylor's army was composed in part of raw volunteers, who had never snuffed the smoke of battle.

Grant as the Messenger to procure Ammunition.

The Americans were brave, but they could hardly be more so than the Mexicans, who had the additional stimulus of standing upon their own soil, fighting for their native land. We cannot find the secret of success in the superior bravery of our troops, and I can only attribute it to the high character, the daring courage, and the matchless skill of our officers. A few such tried and trusty spirits as Grant would leaven any army, and render it capable of performing seeming miracles.

President Pierce, himself a general in the war with Mexico, as a representative in Congress, years before, spoke and voted against the appropriations for the Military Academy at West Point, being heartily opposed to the institution. As a soldier in this brief and decisive contest, he had an opportunity to behold the representatives of the Academy in the storm of battle, and in the active operations of the siege and the march. He saw that West Point fought out that bloody war, and won that series of brilliant victories; and it is creditable to him to have acknowledged his error in this matter, however unrepentant he may be over other and more glaring blunders.

Soon after the battle of Monterey, Lieutenant Grant's regiment was sent to Vera Cruz to swell the grand army which was to march directly to the Halls of the Montezumas.