XIII DECEMBER

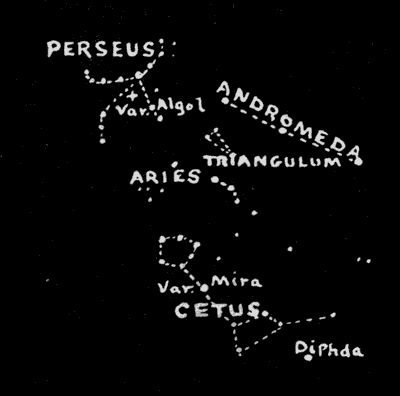

The eastern half of the sky on early December evenings is adorned with some of the finest star-groups in the heavens; but as we are considering for each month only the constellations that lie on or near the meridian in the early evening hours, we must turn our eyes for the present from the sparkling brilliants in the east to the stars in the less conspicuous groups of Aries, The Ram, and Cetus, The Whale. We will also become acquainted this month with the beautiful and interesting constellation of Perseus, the hero of mythical fame to whom we referred last month in connection with the legend of Cepheus and Cassiopeia. Cetus, you will recall, represents the sea-monster sent to devour Andromeda, the daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia. We have included the constellation of Andromeda in our diagram for this month, since it is so closely associated in legend with the constellations of Perseus and Cetus, though we also showed it last month.

The brightest star in Perseus, known as Alpha Persei, is at the center of a curved line of stars that is concave or hollow toward the northeast. This line of stars is called the Segment of Perseus, and it lies along the path of the Milky Way, which passes from this point in a northwesterly direction into Cassiopeia. According to the legend, Perseus, in his great haste to rescue the maiden from Cetus, the monster, stirred up a great dust, which is represented by the numberless faint stars in the Milky Way at this point. The star Alpha is in the midst of one of the finest regions of the heavens for the possessor of a good field-glass or small telescope.

A short distance to the southwest of Alpha is one of the most interesting objects in the heavens. To the ancients, it represented the baleful, winking demon-eye in the head of the snaky-locked Gorgon, Medusa, whom Perseus vanquished in one of his earliest exploits and whose head he carried in his hand at the time of the rescue of Andromeda. To the astronomers, however, Algol is known as Beta Persei, a star that has been found to consist of two stars revolving about each other and separated by a distance not much greater than their own diameters. One of the stars is so faint that we speak of it as a dark star, though it does emit a faint light. Once in every revolution the faint star passes directly between us and the bright star and partly eclipses it, shutting off five-sixths of its light. This happens with great regularity once in a little less than three days. It is for this reason that Algol varies in brightness in this period. There are a number of stars that vary in brightness in a similar manner. Their periods of light-change are all very short, and the astronomers call them eclipsing variables. At its brightest, Algol is slightly brighter than the star nearest to it in Andromeda, which is an excellent star with which to compare it.

December—Perseus, Aries and Cetus

Perseus is another one of the constellations lying in the Milky Way in which temporary stars or novas have suddenly flashed forth. At the point indicated by a cross in the diagram, Dr. Anderson, an amateur astronomer of Scotland, found on February 21, 1901, a new star as brilliant as the pole-star. On the following day it became brighter than a star of the first magnitude. A day later it had lost a third of its light, and in a few weeks it was invisible without the aid of a telescope. In a year it was invisible in all except the most powerful telescopes. With such telescopes, it may still be seen as a very faint nebulous light.

Triangulum and Aries are two rather inconspicuous constellations that lie on, or close to, the meridian at this time. There is nothing remarkable about either of these groups, except that Aries is one of the twelve zodiacal constellations. Some centuries ago, the sun was to be found in Aries at the beginning of spring and the position it occupies in the sky at that time was called the First Point in Aries. As this point is slowly shifting westward, as we have explained elsewhere, the sun is now to be found in Pisces, instead of Aries at the beginning of spring and does not enter Aries until a month later. Pisces was one of the constellations for November and we showed in that constellation the present position of the sun at the beginning of spring.

Two stars in Aries—Alpha and Beta—are fairly bright, Alpha being fully as bright as the brightest star in Andromeda. Beta lies a short distance to the southwest of Alpha, and a little to the southwest of Beta is Gamma, the three stars forming a short curved line of stars that distinguishes this constellation from other groups. The remaining stars in Aries are all faint.

Just south of Aries lies the head of Cetus, The Whale. This is an enormous constellation that extends far to the southwest, below a part of Pisces, which runs in between Andromeda and Cetus. Its brightest star, Beta, Diphda, or Deneb Kaitos, as it is severally called, stands quite alone not far above the southwestern horizon. It is almost due south of Alpha Andromedæ, the star in Andromeda farthest to the west, which it exactly equals in brightness. The head of Cetus is marked by a five-sided figure composed of stars that are all faint with the single exception of Alpha, which is fairly bright, though inferior to Beta or Diphda.

Cetus, though made up chiefly of faint stars, and on the whole uninteresting, contains one of the most peculiar objects in the heavens, the star known as Omicron Ceti or Mira (The Wonderful). This star suddenly rises from invisibility nearly to the brightness of a first-magnitude star for a short period once every eleven months. Mira was the first known variable star. Its remarkable periodic change in brightness was discovered by Fabricius in the year 1596, so its peculiar behavior has been under observation for three hundred and twenty-five years. It is called a long-period variable star, because its variations of light take place in a period of months instead of a few hours or days, as is the case with stars such as Algol. Mira is not only a wonderful star, it is a mysterious star as well, for the cause of its light-changes are not known, as in the case of Algol where the loss of light is produced by a dark star passing in front of a brighter star. Mira is a deep-red star, as are all long-period variable stars that change irregularly in brightness. It is visible without a telescope for only one month or six weeks out of the eleven months. During the remainder of this time, it sometimes loses so much of its light that it cannot be found with telescopes of considerable size. Its periods of light-change are quite variable as is also the amount of light it gains at different appearances.

It is believed that the cause of the light-changes of Mira is to be found within the star itself. It has been thought that dense clouds of vapors may surround these comparatively cool, red stars and that the imprisoned heat finally bursts through these vapors and we see for a short time the glowing gases below; then the vapors once more collect for a long period, to be followed by another sudden outburst of heat and light.

It is interesting to remember in this connection that our own sun has been found to be slightly variable in the amount of light and heat that it gives forth at different times, and the cause of its changes in light and heat are believed to lie within the sun itself.