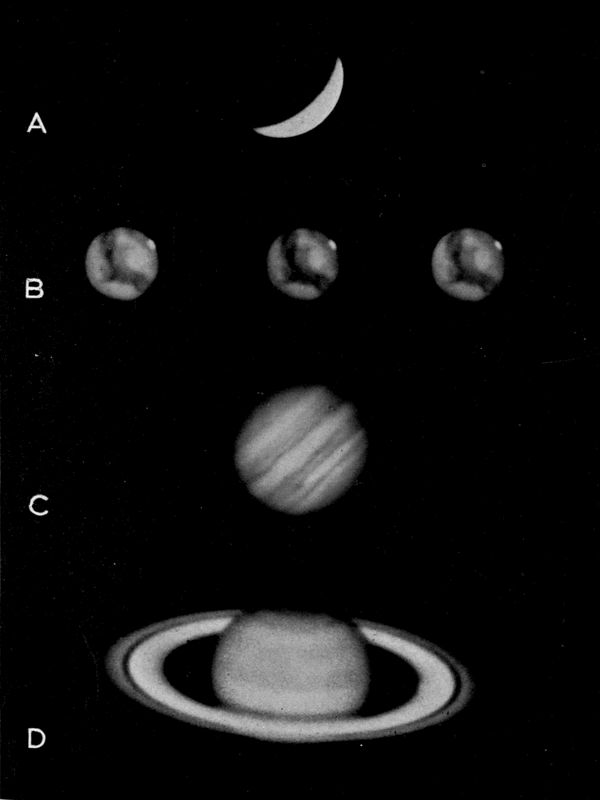

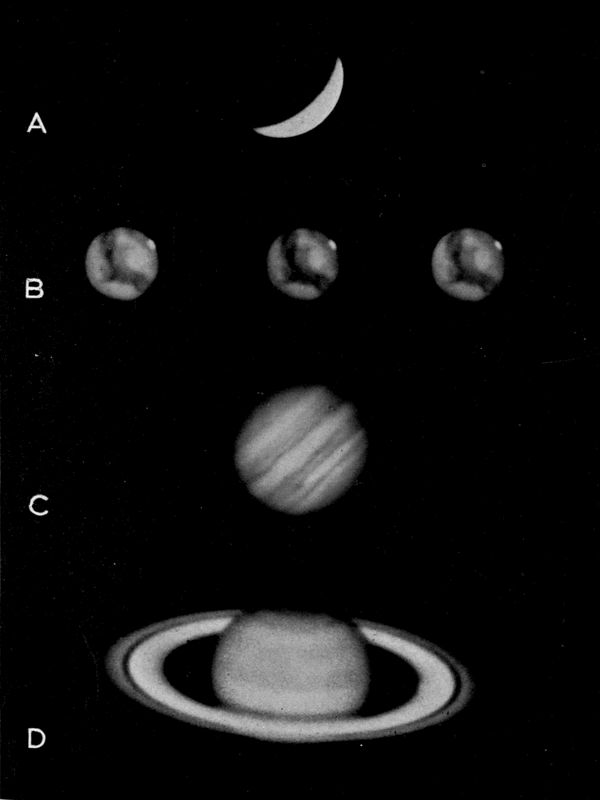

A. Venus. B. Mars. C. Jupiter. D. Saturn.

Taken by Prof. E. E. Barnard with the 40-inch telescope of the Yerkes Observatory, with exception of Saturn, which was taken by Prof. Barnard on Mt. Wilson.

Note: The reader must bear in mind that the telescopic views of the four planets have not been reduced to the same scale and so are not to be compared in size.

The terrestrial planets are the pigmies of the solar system, the outer planets are the giants. The densities of the planets Mercury, Venus, Earth and Mars are several times greater than the density of water. They are all extremely heavy bodies for their size, and probably have rigid interiors with surface crusts.

The existence of life on Mercury is made impossible by the absence of an atmosphere. Venus and Mars both have atmospheres and it is possible that both of these planets may support life. Mars has probably been the most discussed of all the planets, though Venus is the Earth's twin planet in size, mass, density and surface gravity, just as Uranus and Neptune are the twins of the outer group. It is now believed that water and vegetation exist on Mars. The reddish color of this planet is supposed to be due to its extensive desert tracts. The nature of certain peculiar markings on this planet, known as canals, still continues to be a matter of dispute. It is generally believed since air, water and vegetation exist on Mars, that some form of animal life also exists there.

The length of the day on Mars is known very accurately, for the rareness of its atmosphere permits us to see readily many of its surface markings. The length of the day is about twenty-four and one-half hours, and the seasonal changes on Mars strongly resemble our own, though the seasons on Mars are twice as long as they are on our own planet since the Martian year is twice as long as the terrestrial year.

The question of life on Venus depends largely upon the length of the planet's rotation period. This is still uncertain since no definite surface markings can be found on the planet by which the period of its rotation can be determined. So dense is the atmosphere of Venus that its surface is, apparently, always hidden from view beneath a canopy of clouds. It is the more general belief that Venus, as well as Mercury, rotates on its axis in the same time that it takes to make a revolution around the sun. In this case the same side of the planet is always turned toward the sun and, as a result, the surface is divided into two hemispheres—one of perpetual day, the other of perpetual night.

This peculiar form of rotation in which the period of rotation and revolution are equal is by no means unknown in the solar system. Our own moon always keeps the same face turned toward the earth and there are reasons for believing that some of the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn rotate in the same manner.

Life on any one of the outer planets is impossible. The density of these planets averages about the same as the density of the sun, which is a little higher than the density of water. The density of Saturn is even less than water. In other words, Saturn would float in water and it is the lightest of all the planets. It is assumed from these facts that the four outer planets are largely in a gaseous condition. They all possess dense atmospheres and, in spite of their huge size, rotate on their axis with great rapidity. The two whose rotation periods are known, Jupiter and Saturn, turn on their axis in about ten hours. On account of this rapid rotation and their gaseous condition both Jupiter and Saturn are noticeably flattened at the poles.

The terrestrial planets are separated from the outer group by a wide gap. Within this space are to be found the asteroid or planetoid group. There are known to be over nine hundred and fifty of these minor bodies whose diameters range from five hundred miles for the largest to three or four miles for the smallest. There are only four asteroids whose diameters exceed one hundred miles and the majority have diameters of less than twenty miles. The total mass of the asteroids is much less than that of the smallest of the planets. It was believed at one time that these small bodies were fragments of a shattered planet, but this view is no longer held. The asteroids as well as the comets and meteors probably represent the material of the primitive solar nebula that was not swept up when the larger planets were formed.

With few exceptions the asteroids are only to be seen in large telescopes and then only as star-like points of light. Most of them are simply huge rocks and all are necessarily devoid of life since such small bodies have not sufficient gravitational force to hold an atmosphere.

The revolution of the planets around the sun and of the satellites of the planets around the primary planets are performed according to known laws of motion that make it possible to foretell the positions of these bodies years in advance. Asteroids and comets also obey these same laws, and after three observations of the positions of one of these bodies have been obtained its future movements can be predicted. All the planets and their satellites are nearly perfect spheres. They all, with few exceptions, rotate on their axes and revolve around the sun, or, in the case of moons, around their primaries, in the same direction, from west to east. Only the two outermost satellites of Jupiter, the outermost satellites of Saturn and the satellites of Uranus and Neptune retrograde or travel in their orbits from east to west, which is opposite to the direction of motion of all the other planets and satellites.

The paths of all the planets around the sun are ellipses that are nearly circular, and they all lie nearly in the same plane. The asteroids have orbits that are more flattened or elliptical and these orbits are in some instances highly inclined to the planetary orbits. The comets have orbits that are usually very elongated ellipses or parabolas. Some of the comets may be only chance visitors to our solar system, though astronomers generally believe that they are all permanent members. Paths of comets pass around the sun at all angles and some comets move in their orbits from west to east, while others move in the opposite direction or retrograde. The behavior of the asteroids and comets is not at all in accord with the theory that was, until recently, universally advanced to explain the origin of the solar system.

Some astronomers have made attempts to modify the nebular hypothesis that has held sway for so many years, in order to make it fit in with more recent discoveries, but others feel that a new theory is now required to explain the origin of the solar system. Several theories have been advanced but no new theory has yet definitely replaced the famous nebular hypothesis of the noted French astronomer La Place.