healthcare professionals across many years has increased the

decline continued though

gap between the number of people who develop cancer and the

2008, according to a recent

number of people who die from it, and ask your students what

report by researchers at the

factors they think are contributing to this increased gap.

same organizations. Point

Students will likely answer that it is the result of increased prevention,

out that this provides

earlier detection, and improved treatment.

evidence that cancer

research has paid off in

3. Invite the students who are still standing to sit, then ask the class

thousands of human lives

whether there is any way to know who will develop cancer and when.

saved. Suggest that some

students may want to

Students may answer that there is no way to know for sure, but, in

consider a career in research.

general, old people, people who smoke, and people exposed to excessive

radiation develop cancer. Accept all reasonable answers without

comment; the purpose of this questioning is to encourage students

to express what they already know about cancer and to highlight the

fact that there is no definitive way to know who will develop cancer. If

students make questionable claims about risk factors or other aspects

of cancer, you may wish to respond that many claims are made about

cancer and then ask students how they could investigate such claims.

You may also wish to point out that Lesson 4, Evaluating Claims about

Cancer , addresses this question.

54

4. Explain that in this lesson, students will learn more about who develops

cancer, when, and why, by assuming the identities of 30 [insert the

number of students in your class] fictitious people who develop cancer

and building a profile of some of the key events in these people’s lives.

Current statistics indicate that 41 percent, or 2 in 5, Americans

will develop invasive cancer during their lifetimes. In this activity,

however, each of the 30 fictitious people develops cancer. The activity

is structured in this way to offer all students similar experiences and

to provide maximum richness and variety to the stories of cancer the

students encounter. Students will be reminded of the 41 percent, or 2 in

5, risk of developing invasive cancer when they complete the questions

on the bottom of Master 1.3, Drawing Conclusions (see Step 18).

5. Direct the students to organize into groups based on the number they

received during the count-off (all students with number 1 should form

a group and so on).

Students will work in groups of four to five throughout the activities in

the module. To ensure that students working together as members of one

group have a common foundation of experience and understanding, we

recommend that you keep students in the same groups for all the activities.

6. Give each student one identity envelope and explain that the outside

of the envelope contains a description of the person that student is

to become. Ask students to read the descriptions on the envelopes

they receive and share who they are with the other members of their

groups. Ask students not to open their envelopes at this time.

We suggest that you do not try to match male students with male names

and female students with female names. Instead, distribute the envelopes

randomly throughout the class. This strategy simplifies the process of

distributing the envelopes and avoids the problem that your class may contain

a different number of males and females than the identity envelopes do.

To make the activity fun, encourage students to read the description

of the person they have “become” to themselves, then introduce

themselves (in first person) to the other members of their group. As

students move through the activity, encourage them to “tell” their

stories to the rest of the group, using first-person language and

representing the person they have become as realistically as they can.

Tip from the field test . Before distributing the envelopes, you may wish

to explain that some students will be asked to assume the identities of

people quite different from themselves (for example, a different sex or

ethnic or cultural group). Explain that this is an inevitable consequence

of the activity’s structure, and ask all students to do the best job they

can representing the people whose identities they have assumed.

7. While students are discussing their new identities, distribute one copy

of Master 1.2, Group Summary , to each student.

55

Student Lesson 1

Cell Biology and Cancer

8. Explain that the students’ task in the next few minutes will be to use

Master 1.2 to summarize information about the lives of the fictitious

people in their group. Point out that the descriptions they just read

contained information about whether each person had a history of

cancer in his or her family. Ask students to use this information to

complete Section 1, Family History, on Master 1.2.

Give the students 1 to 2 minutes to complete this task. If necessary,

explain that having a “history of cancer in the family” means having a

biological relative (grandparent, parent, sibling, aunt, or uncle) who has

or has had cancer.

9. Explain that inside each envelope is a set of four cards that provide

additional information about each person’s life. Direct students to remove

the cards from their envelopes and place them face down on the desks in

front of them so that the cards are in sequence, with the card labeled

“0–19” years on top and the card labeled “60+ years” on the bottom.

Each student should have four cards. Some of the fictitious people

were “born” in the early 1900s and are “old” enough to be 70 or 80;

others were born much later (for example, in the 1970s or 1980s).

Nevertheless, we have extended these people’s lives to 60+ years, even

though this time stretches well into the 21st century. This approach

allows the activity to illustrate a wide range in choices and healthcare

options across the 20th century. The approach also gives each student a

chance to have four cards and participate to the end of the activity.

10. Invite the students to turn over and read the cards labeled “0–19.”

Give the students a few minutes to share the information they learn

with the other members of their groups, then challenge them to use

this information to complete the “0–19 years” column in Section 2,

Cancer History, of Master 1.2.

To heighten the activity’s drama, do not allow students to read all their

cards at once. Insist that students in each group progress through the

life stages in sequence together.

As students begin to read their cards, they may need help

understanding how to fill in Section 2 of Master 1.2.

11. Instruct students to turn over the rest of their cards in sequence,

share the information the cards contain, then use this information to

complete Section 2 of their Group Summary. Challenge the students to

look for patterns or trends in the data they are collecting and explain

that when the class pools all of its data, the students will be able to

determine the degree to which the patterns they see in their group’s

data also appear in the pooled data.

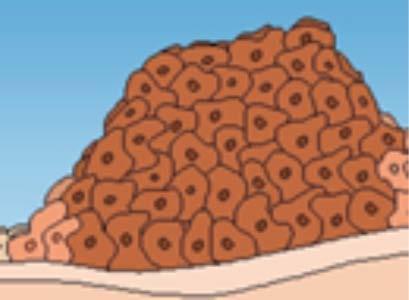

The black dot that appears on one of the four cards for each person shows

when mutations may have occurred that eventually contributed to the

development of cancer. Some students may ask what this dot represents.

56

Do not explain the dot at this point.

12. After the students complete Section 2 of their Group Summary, ask

them if they noticed any choices or other risk factors that may be

related to the cancer people developed. Instruct students to go back

through their cards to identify these factors, then list them in Section

3, Possible Risk Factors, of Master 1.2.

Some of these risk factors are smoking, sun exposure, high-fat diet, early

sexual activity, and genetic predisposition for cancer. A major factor that

is not specifically noted is aging. The explanation for increased incidence of

cancer with aging is explored in Lesson 3, Cancer as a Multistep Process .

13. As the groups complete their summaries, distribute one copy of Master

1.3, Drawing Conclusions from the Faces of Cancer , to each student.

14. Project Master 1.4, Summary Profile of the Faces of Cancer , and explain that you will complete the table as the groups share the information

they have collected. Explain that as you complete each row of the

table, you will give the groups 2 to 3 minutes to discuss and record

a conclusion they can make from the pooled data.

To illustrate, ask each group to report how many people in that

group did and did not have a history of cancer in their families.

Then, ask the students what pattern they see in the pooled data and

what conclusion it leads them to make. Direct students to write their

answers in the space provided on the top half of Master 1.3.

Students should see that some people have a family history of cancer whereas

other people do not. If students have difficulty expressing this idea, ask

them whether the number of “yes” answers (the number of people who did

have a family history of cancer) equals the total number of people who

developed cancer (everyone in the class), and what this discrepancy means.

15. Complete each row of Master 1.4 in turn, first asking groups to share

their data with you, then totaling the data and entering them into the

table. After you complete each row, give the groups time to discuss

and agree on their conclusion and add it to their copies of Master 1.3.

• In the second row, students should see that the number of people who

develop cancer increases with age (that is, the incidence of cancer

increases with age). If students have difficulty expressing this idea,

you may wish to ask a guiding question such as, “What do you notice

about the number of people who develop cancer in each life stage?”

Encourage students to write their conclusion as a statement (for example,

“The number of people who develop cancer increases with age.”).

• In the third row, students should see that cancer can develop in

almost any tissue and organ in the body. They also may note that

some types of cancer are more common than others.

57

Student Lesson 1

Cell Biology and Cancer

You may wish to ask students whether the fact that no one in this

sample developed brain or uterine cancer means no one in the U.S.

population gets this type of cancer. Students should recognize that this

is not true. You also may wish to invite students to suggest other types

of cancer that did not occur in this population and list them under

“other” in the third row of the table.

• In the fourth row, students should see that some people make choices

or experience life events that increase their risk of developing cancer.

Tip from the field test . Students may have difficulty distinguishing factors

that increase risk for cancer from those that do not. If so, ask them how

they could find out about risk factors. You may wish to refer students to

the Web site for the National Cancer Institute as an excellent source for

current and reputable information about cancer ( http://www.nci.nih.gov ).

16. Ask whether anyone can suggest what the black dot on each person’s

set of cards might mean. Entertain several answers. If necessary,

explain that these dots represent the period of life during which

mutations may have occurred that eventually contributed to the

development of cancer. Ask the students to discuss in their groups

what they notice about the dots. Explain that students will learn more

about these mutations in Lesson 2.

Give the students several minutes to look at the dots and discuss what

they observe. If students seem to be confused about what they should

be noticing, ask them guiding questions such as, “What do you notice

about the period of life in which each person’s dot occurs and the

period in which that person’s cancer was detected?”

Be sure that students understand the difference between the period of

life in which the mutations associated with the development of cancer

occurred and the period in which the cancer was detected. In some cases,

the dot appears in the same period of life that the cancer was detected.

In most cases, however, the dot appears many years before that period.

17. Ask two or three groups to report what they observed about the dots and

initiate a class discussion about the significance of these observations.

Help students understand that cancer develops across time and often

many years intervene between the first cancerous changes and the

symptoms that cause a person to seek medical help.

As part of this discussion, you may also wish to ask students

• what factors in people’s lives improve their chance of recovering

from cancer (for example, early detection and treatment);

• what factors reduce their chances of early detection (for example,

poor access to health care, either because of where they live or

their socioeconomic status); and

• what factors increase their chances of early detection (for example,

participation in opportunities to be screened for cancer)?

58

Challenge students to support their answers by referring to specific

people they learned about in this activity.

18. Close the activity by asking students to complete the Discussion

Questions on the bottom of Master 1.3 either in class or as homework.

Briefly discuss their answers with them at the end of the period or at

the beginning of the next.

Collect and review the

Question 1. In this activity, all students in the class assumed the role of

students’ completed

someone who developed cancer sometime in his or her lifetime. Is this

worksheets to assess

an accurate representation of the risk of cancer among the American

their understanding

population? Explain your answer.

of the lesson’s

major concepts.

No, this is not an accurate representation. Students should remember

the opening exercise in which they learned that current statistics

indicate that 41 percent, or 2 in 5, of Americans develop invasive cancer

sometime in their lines. Point out that in this activity, students studied

30 people who all got cancer, but this does not mean that everyone will

get cancer in his or her lifetime.

Point out as well that students should not extrapolate from the rates of

cancer illustrated in the activity. Although the general trends illustrated

in these 30 people are accurate (for example, rates for lung, colon, and

breast cancer are higher than rates for cervical, pancreatic, and ovarian

cancer), rates for other cancers are artificially exaggerated as a result of

the small sample size. A striking example of this exaggeration occurs

in the case of retinoblastoma. We included retinoblastoma to illustrate

an example of a hereditary cancer, even though its incidence in the U.S.

population is less than 1 in 1 million per year.

Question 2. What explanation can you offer for the observation you made

about the incidence of cancer compared with age?

Answers will vary. Some students may suggest that it is related to the

fact that cancer develops across time (which they learned when you

Asking students to name the

discussed the black dots with them). Because older people have lived

most important thing they

longer, they have a greater chance of developing it. Students will return

learned challenges them to

to this question in Lesson 3, Cancer as a Multistep Process .

identify the lesson’s key

ideas. If students have

Question 3. What is the most interesting or surprising thing you learned

difficulty with this, ask

from this activity? What is the most important? Why?

questions based on the

objectives in At a Glance.

Answers will vary.

Extend or enrich this activity by asking students to bring to class current

Potential

newspaper or magazine articles about cancer. Display these in your classroom

Extensions

and, at the close of Lesson 5, invite students to comment on them, drawing

on what they learned about cancer during the preceding lessons.

59

Student Lesson 1

Cell Biology and Cancer

Lesson 1 Organizer

What the Teacher Does

Page and Step

Ask students to count off in sets of 6 (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 1, 2, etc.) and

Page 53

remember their number.

Step 1

Explain that statistics are often used to characterize large populations.

Page 53

In this activity, the classroom represents the U.S. population.

Step 2

• Ask students with numbers 2, 3, 5, or 6 to stand. This represents the

4 of 6 people in the U.S. who will have children. Ask students to sit.

• Ask students with numbers 3 or 6 to stand. This represents the 2

in 6 people who will be involved in an alcohol-related automobile

accident sometime in their lifetimes. Ask students to sit.

• Ask students with numbers 1 or 4 to stand. Explain that about 2

in 6 people in the room will develop cancer sometime during their

lifetimes.

• Ask about one-fourth of the standing students to sit.

• The number of students left standing represents the approximate

percentage of the U.S. population that will die of cancer (about

25 percent).

• Tell students that the work of scientists and health professionals has

increased the gap between the number of people diagnosed with

cancer and the number who die from it.

• Ask students what factors have contributed to this increased gap.

Have all students sit. Ask the class if there is any way to know who will Page 54

develop cancer and when.

Step 3

Inform students that in this activity they will learn more about who

Page 55

develops cancer, when, and why by assuming the identities of fictitious Steps 4

people. Have students to organize into groups according to their

and 5

numbers from Step 1.

Give each student one identity envelope. Explain that the outside of

Page 56

the envelope contains a description of the person that student will

Step 6

become. Ask students

• to read the descriptions on the envelope,

• to share that information with other group members, and

• not to open their envelopes .

60

What the Teacher Does

Page and Step

Give one copy of Master 1.2 to each student and ask groups to

Page 55

complete Section 1.

Steps 7

and 8

Direct students to remove cards from envelopes and place them face

Page 56

down on their desks so that cards are in sequence, with the card

Step 9

labeled “0–19 years” on top.

Ask students to turn over and read cards labeled “0–19 years” and

Page 56

to share information with their group members. Instruct groups to

Step 10

complete the “0–19 years” column in Section 2 of Master 1.2 .

Instruct students to turn over the rest of their cards in sequence

Page 56

and then to complete Section 2 of their group summary. Challenge

Steps 11

students to look for patterns in the data and to list possible risk factors and 12

in Section 3 of Master 1.2 .

Give each student one copy of Master 1.3 and project Master 1.4 .

Page 57

Explain that you will complete the table as groups share information

Steps

they have collected. For each row completed, give groups 2–3 minutes

13–15

to discuss and record a conclusion (such as patterns) they can make

from the pooled data. Direct students to write their answers on their

copies of Master 1.3 .

Ask for suggestions about what the black dot on each person’s set

Page 58

of cards might mean. (The dot represents when mutations that

Step 16

contributed to the development of cancer may have occurred.) Ask

students to discuss what they notice about the dots.

Ask a few groups to report what they observed about the dots and

Page 58

discuss the significance of these observations as a class.

Step 17

Close by asking students to complete the discussion questions on

Page 59

Master 1.3 . Briefly discuss answers.

Step 18

= Involves copying a master.

= Involves making a transparency.

61

Student Lesson 1

L E S S O N 2

Explore/Explain

Cancer and

the Cell Cycle

Focus

At a Glance

Students start by reviewing four historical observations about agents that

Page 1 Page 2 Page 3 Page 4 Page 5 Page 6 Page 7 Page 8 Page 9 Page 10 Page 11 Page 12 Page 13 Page 14 Page 15 Page 16 Page 17