Repurposing

Suppor t Mechanisms

Transfer

Cost, Assessing Information Value, Technologies

Record of

Data

Disposal

Discarded Data

Established Processes, Technologies

108

P r o c e s s

level of security, assessing the value of information, and a variety of enabling technologies.

Throwing away information isn’t free, especially if the information must be processed extensively before disposal. For example, the level of security needed at this stage of the KM life cycle can be extremely high, depending on the nature of the information to be discarded. Since this may be the first and only time that information generated within the organization is handled by the public disposal system, the potential for corporate espionage or even accidental discovery exists. For example, simply throwing old servers and PCs in a Dumpster may allow the competition to recover the hardware and explore information on the hard drives.

Someone, such as the librarian, must have the authority to assess the value of maintaining information in the corporation versus disposing of it.

Knowledge Management Infrastructure

The discussion of the Knowledge Management life cycle has assumed that an infrastructure of sorts provides the support necessary for each phase of the life cycle. This infrastructure consists of tracking, standards, and methods of insuring security and privacy of information. In most organizations, this infrastructure brings with it considerable overhead for both the company and the knowledge workers. For example, generating and maintaining information is difficult enough, but it also must be tracked, just as a book is tracked by a librarian in a public library.

Besides merely tracking information at every phase of the KM life cycle, standards for processing and handling information must be followed to guarantee security, accuracy, privacy, and appropriate access. Just as libraries don’t condone readers replacing books on the shelves for fear that the books might be shelved incorrectly and therefore be temporarily

“lost” to other patrons, knowledge workers must abide by rules established to maximize the usefulness of information throughout the KM life cycle.

109

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t Chapter 5 continues the discussion of the phases of the KM life cycle, from the perspective of the vast array of technologies that can be applied to enable the infrastructure and the individual phases of the life cycle.

Summary

The Knowledge Management life cycle is perhaps best described as a web of interrelated phases. Each phase is associated with issues that must addressed by supporting mechanisms and can be enabled by information technology. Most of these issues revolve around economics, accessibility, intellectual property, the underlying infrastructure, and the commitment and active role of management in setting policy. In addition, the issues regarding the information itself need supporting mechanisms, such as establishing and enforcing standards, utilizing the contribution of knowledge workers, and managing the overall process.

Do not be desirous of having things done quickly.

Do not look at small advantages. Desiring to have things done quickly prevents their being done thoroughly. Looking at small advantages prevents great affairs from being accomplished.

—Confucius

110

C H A P T E R 5

Technology

After reading this chapter you will be able to

• Appreciate the range of available technologies that can support a Knowledge Management initiative

• Understand the significance of selecting or developing a controlled vocabulary as part of a Knowledge Management initiative

• Understand what differentiates traditional tools and applications from so-called Knowledge Management tools

• Appreciate the technological infrastructure needed to support a successful Knowledge Management initiative

• Recognize the potential of disruptive information technologies to change the future of Knowledge Management Knowledge Management (KM) can be adopted as a strategy with little or no dependence on what’s considered high tech today. The earliest knowledge workers did just fine with clay tablets of various shapes to archive and retrieve information for the local government.

Similarly, communities of practice need little more than a physical space so that members can meet to discuss ideas. On a personal level, a chief executive officer (CEO) can do just fine without a personal digital assistant (PDA), relying, instead, on a notebook maintained by his or her 111

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t assistant. Similarly, physicians, lawyers, and other knowledge workers don’t need computer-based systems to do their work.

That said, Knowledge Management, like most other business strategies, can have more powerful results—as measured by the bottom line—

with the appropriate use of information technology. As illustrated in Exhibit 5.1, the organic or unassisted approach contrasts significantly with the technologic approach based on computers, databases, and applications. Although there is considerable overlap in the two approaches, key differences are in the transaction volume ideal organization size, scalability, type of knowledge involved, and initial cost.

A technologic approach to Knowledge Management has a much higher initial cost, is inherently more scalable, and can handle a much greater transaction volume than an unassisted knowledge worker. For example, whereas an unaided customer service representative might be able to handle perhaps 1,000 customer complaints a month, a technology-enabled rep might be able to cover thousands of customer interactions per minute. Because of the leverage provided by technology, such as a software robot (bot) that interacts with customers over e-mail, the rep can work in an oversight capacity. The bot can handle most e-mail queries, supplying answers culled from past interactions with live customer service reps, and, on the rare occasions when the system can’t adequately resolve a customer’s issues, can pass the customer on to a live rep.

Technology in support of Knowledge Management isn’t necessary or even optimal in every instance. For example, if the issues that have to be dealt with are subtle and require a very rich knowledge of the area, an expert knowledge worker or knowledge analyst may be the best option.

Similarly, although technologies supportive of Knowledge Management can be applied successfully to organizations of any size, extensive investments in technology are generally practical only in medium-size to large companies. The organic approach is generally more practical for small to medium-size organizations.

112

T e c h n o l o g y

From an implementation perspective, the key issues with a technologic approach are training the knowledge workers to use the technology appropriately and to use the appropriate controlled vocabulary. The organic approach, in contrast, necessarily focuses on the knowledge worker’s skills in interacting with people and within retaining their knowledge in the organization.

Perhaps the most significant way technology enables the KM process is that it can provide virtual meeting space for communities of practice.

Although a knowledge analyst or other knowledge worker can help organize a meeting, there is always the issue of meeting place, time, and other logistics. When collaborative technologies are available to provide E X H I B I T 5 . 1

Technology versus Organic Knowledge Management

Focus

Technology

Organic

Enablers

Computers, databases, and

Knowledge workers

applications

Human resources

Knowledge engineers

Knowledge analysts

Key issues

Vocabular y, training,

People skills, knowledge

knowledge workers

retention

Scalability

High

Low

Initial cost

High

Low

Ideal organization size

Small to large

Small to medium

Geographical

None

Time zones, proximity

constraints

limitations

Volume capacity

Thousands per minute

Thousands per month

Primar y users

Customers, knowledge

Knowledge workers,

workers, managers, vir tual

high-end customers

communities of practice

Example company

Dell Computer

Hewlett-Packard

Applicability

Generic problems

Special cases

Knowledge required

Obvious, readily apparent,

Rich, subtle, tacit

explicit

113

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t I N T H E R E A L W O R L D

People versus Processors

Dell Computer allows customers to configure PCs with more than 40,000 combinations of hardware and software through its web site. Instead of dealing with an engineer or salesperson, customers interact directly with Dell’s web site to compare prices and capabilities of various configurations. Although many customers then turn to the phone to actually place the order, the system saves Dell from having to train sales representatives on the continuous stream of new products and configurations.

The technology approach to Knowledge Management isn’t a panacea, however. For example, even though it’s a technology company, Hewlett-Packard relies heavily on the organic approach, using human knowledge workers in situations that require on-site, hands-on dissemination of information.

TEAMFLY

a virtual meeting, they can be held as frequently as necessary, for short periods, with no overhead of walking or traveling to a meeting place.

This chapter explores the many enabling technologies that can be applied to Knowledge Management at both the corporate level and the level of the individual knowledge worker. Before delving into a description of these and other enabling technologies, consider the challenges being addressed at the Custom Gene Factory.

Electronic Whiteboard

Like most other firms, Custom Gene Factory (CGF) is challenged with delivering an economically viable service to its customers in a highly competitive industry while investing heavily in new product development. As a result, the research and development department (R&D) is under pressure to develop new processes and communicate these ideas 114

Team-Fly®

T e c h n o l o g y

to production staff so that they can quickly move the most promising developments out of the laboratory and into trials with pharmaceutical firms. As such, the knowledge workers in the R&D department spend a great deal of time in ad hoc brainstorming sessions, where everyone associated with a project, in any department, comes up with as many unusual solutions as possible to move a product or process forward.

However, because CGF’s campus is spread out over six buildings and some of the pharmaceutical firm partners that are part of the community of practice are located in other cities, an unacceptably high overhead is associated with bringing the stakeholders together for regular meetings.

To facilitate the brainstorming sessions in a way that fits everyone’s schedules, the chief knowledge officer (CKO) attends several of the meetings as an unobtrusive observer to determine the real needs of the T I P S & T E C H N I Q U E S

Suggest, Don’t Tell

One of the basic principles of computer interface design is that the computer should be subservient to the human operator. When this principle is violated, operators, including highly educated knowledge workers, tend to be put off and, in some cases, threatened. The most successful decision-making programs respect human decision makers and merely suggest—don’t tell—them what to do.

Perry Miller who developed the Critiquing system in the 1980s, was first to recognize the importance of allowing the human operator to feel in control of the decision-making process. The Critiquing system acts as a sounding board for organizing physicians’ ideas, expressing agreement, or suggesting reasoned alternatives. This approach recognizes physicians’ need to exercise control and places the computer in a subservient, nonthreatening role.

115

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t members. He discovers that the group relies heavily on the whiteboard, with the requisite note-taker who attempts to copy the contents of the board every few minutes. The meetings include multiple verbal exchanges, printed handouts, and the personal, face-to-face interchanges. Furthermore, at the start of every meeting, the group leader has to bring those who couldn’t attend the previous meeting up to speed by reviewing the ideas offered and decisions made in their absence.

Because of the scheduling problems, it’s rare to have every stakeholder in the meeting at once, and some issues have to be discussed privately, further adding to the communications and time overhead for those involved in the meeting.

The CKO floats the idea of a computer-based collaborative system to the group. The ideal system would provide real-time video, voice, an electronic whiteboard, and text interchange with every member of the group. It also would keep a record of the exchanges arranged by date and topic. The group members agree to consider the options at the next meeting.

In the interim, the CKO consults with the chief information officer (CIO) to identify three software packages that are compatible with the corporate intranet, the pharmaceutical firms’ networks, and the corporate hardware, and presents the options to the group. After a lengthy discussion, the group picks a solution. It’s another month before the software and hardware upgrades—including desktop digital cameras—

are installed and six weeks more for everyone to go through training.

The first few meetings are less than ideal for those who enjoy the face-to-face interaction, but for everyone else, the system is a significant time-saver. With the collaborative system in place, everyone in the brainstorming group can attend the virtual meetings. Furthermore, everyone with access privileges can read through and add to the discussion asynchronously.

116

T e c h n o l o g y

Issues

The work at CGF illustrates several issues regarding the use of technology to enable a KM program:

• Information technology can be critical in enabling KM

processes. Numerous technologies are available to enable organizations to leverage their intellectual capital.

• Every technology initiative must involve the CIO or other representative of the information services (IS) group.

Collaborative tools that involve sharing information between departments and especially between the company and external customers require compete cooperation with the IS department.

• Integrating technology into an organization takes time. Even though the collaborative technology paralleled a community of practice already in place at CGF, time was required for the IS department to install and test the hardware and software; participants needed training time; and finally, when the system was up and running, time was required to establish procedures for the group activity.

• It’s how technology is used, not the technology’s inherent capabilities, that define whether it’s capable of enabling a KM

program.

Enabling the Knowledge Management Process

The technologies available to enable the Knowledge Management process span the continuum from low-tech tools, such as pen and paper, to high-tech expert systems and virtual reality displays. For example, the telephone, tape recorders, whiteboards, and other technologies that most of us take for granted are enabling technologies in that they facilitate some aspects of the KM life cycle. However, when most people speak of enabling technologies, they’re referring to more high-tech 117

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t tools, such as PDAs, that provide some advantages over pen and paper.

That distinction is a matter of degree and user experience. For example, in the late 1800s, the telephone switchboard was a disruptive technology that enabled business owners to collaborate with each other and their staff in real time over distances of several miles.

Exhibit 5.2 presents a wide range of enabling technologies, from authoring and decision support tools to controlled vocabularies and database tools, that can be used to enable various phases of the KM life cycle. In general, these technologies serve as intellectual levers that provide the connectivity needed to efficiently transfer information among knowledge workers, either in real time or asynchronously. In this regard, a database archive can be thought of as a storage area that adds a significant delay to the communications.

E X H I B I T 5 . 2

Life Cycle Phase

Primary Enabling Technologies

Creation/acquisition

Authoring tools, inter face tools, data capture tools, decision suppor t tools, simulations, professional databases, application-specific programs, database tools, pattern matching, groupware, controlled

vocabularies, infrastructure, graphics tools

Modification

Authoring tools, decision suppor t tools, infrastructure Use

Inter face tools, visualization tools, decision suppor t tools, simulations, application-specific programs, database tools, pattern matching, groupware,

infrastructure, web tools

Archiving

Database tools, cataloging tools, controlled

vocabularies, infrastructure

Transfer

Groupware, infrastructure

Translation/repurposing

Decision suppor t tools, simulations, database tools, infrastructure

Access

Inter face tools, database tools, pattern matching, groupware, controlled vocabularies, infrastructure Disposal

Database tools, infrastructure

118

T e c h n o l o g y

Knowledge Management draws on technologies and approaches developed in virtually every field of computer science. For example, knowledge creation and acquisition benefit from technologies such as data mining, text summarizing, a variety of graphical tools, the use of intelligent agents, and a variety of information retrieval methodologies.

Knowledge archiving and access benefit from information repositories and database tools. Knowledge use and transfer benefit from interface tools, intranets and internets, groupware, decision support tools, and collaborative systems. In addition, virtually all of the technologies involved in the KM life cycle assume an infrastructure capable of supporting moderate- to high-speed connectivity, security, and some degree of fault tolerance. The next sections describe the primary classes of enabling technologies listed in Exhibit 5.2 in more detail.

Groupware

Groupware typically is defined as any software that enables group collaboration over a network. Examples of groupware include shared authoring tools, electronic whiteboards, videoconferencing tools, online forums, e-mail, online screen sharing, and multimodal conferencing. Each of these technologies holds the potential to increase collaboration at a distance, reducing the cost of travel and the time knowledge workers waste in transit.

Shared authoring tools include common word processing programs, graphics programs, and sound editing utilities. Although they’re not often sold as such, many stand-alone applications can be considered groupware if they can access and modify a document on the web or a common server.

Most shared authoring tools must be used asynchronously, in that only one person at a time can make changes to a document.

E-mail systems that support asynchronous text-based communications are probably the most often used groupware. A related technology, 119

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t online forums, is a real-time, text-based system that allows group posting and response to text messages. An online forum is self-archiving, in that the sequence of text-based conversations involving dozens or even hundreds of contributors is maintained for review by others. Instant messaging is an upcoming form of groupware that allows knowledge workers working away from their desks to exchange short packets of information. However, unlike online forums, the string of messages isn’t stored automatically for future reference.

Screen sharing allows a user with the appropriate access privileges to connect to and take control of a remote PC. Screen sharing is especially popular in training and troubleshooting situations, where a support person can show the trainee at a remote site how to perform an operation and then watch as the trainee attempts to do the operation.

Even higher up the evolutionary ladder of groupware is the electronic whiteboard. This technology, expressly designed for group collaboration, provides a virtual whiteboard drawing space that enables multiple collabo-rators to take turns authoring and modifying hand-drawn graphics, highlighting points of interest on digital images, or simply posting a slide for a presentation.Whiteboards often are used in conjunction with other products, such as videoconferencing, the real-time, multi-way broadcasting of video and audio.

Because of network bandwidth limitations, videoconferencing often is configured to use the telephone lines for audio and the Internet or other network for the video channels. However, when the bandwidth is sufficient, many companies embrace multimodal conferencing to enable real-time collaboration. Multimodal conferencing represents the pinnacle of groupware, in that the technology supports real-time group sharing of an electronic whiteboard, a text forum, audio, and multiple-channel video.

As illustrated in Exhibit 5.3, groupware differs in responsiveness and the maximum number of simultaneous users that can be accommodated.

120

T e c h n o l o g y

E X H I B I T 5 . 3

Shar

S

ed

E-Ma

ail

a

uthoring

Au

ut

Text

Tools

T

Forums

Electr

El

Elect onic

Whiteboard

Video

Confer

nferencing

en

enc

Screen

Sharing

Multimodal

ultimod

Conferencing

Max Simultaneous Users

Responsiveness

For example, an e-mail system can handle a virtually unlimited number of users, as long as they don’t try to send e-mail at once. Also, users typically read and respond to e-mail at different times. In contrast, videoconferencing, which is real-time communication, supports a limited number of users because of limitations in the bandwidth of the network and the processing capacity of each user’s PC.

Pattern Matching

Pattern matching, the major feature ascribed to programs in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), provides the foundation for many aspects of Knowledge Management. From a business perspective, the technology ideally enables a knowledge worker with relatively little experience to make decisions that otherwise would have required someone with much more experience. Examples of pattern matching applications in the realm of AI include expert systems, intelligent agents, and machine learning systems.

121

E S S E N T I A L S o f K n o w l e d g e M a n a g e m e n t Expert Systems

Pattern matching is the basic technology underlying expert systems—

programs that can make humanlike decisions, especially reasoning under conditions of uncertainty. Expert systems are also useful in helping experts work out a process, such as medical diagnosis. Once the process is distilled into rules, the logic can be incorporated into the standard programming environment or delivered as graphical decision diagram.

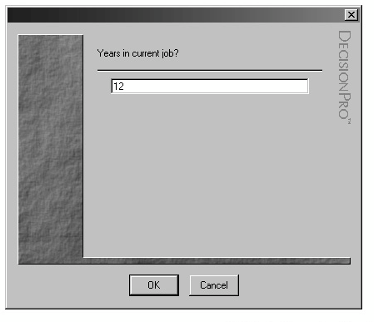

As an example of how pattern matching technology can be applied to Knowledge Management, consider the system illustrated in Exhibit 5.4. In this rule-based expert system, DecisionPro, by Vanguard Software, E X H I B I T 5 . 4

Bank Loan Qualifications

Candidate must earn enough income

to cover the loan—at least five times

the amount to be borrowed and not

less than $25,000 per year.

Candidate must be considered

“stable”—at least 30 years old or

married and has held current job for

at least three years.

Candidate must be an adult—at least

18 years old.

Sufficient income is defined as having an

Income=WASK(“Candidate’s annual income? ”)

income greater than 5 times the amount

Unevaluated

borrowed and greater than 25000 per year

Sufficient Income=

Principal=WASK(“Loan amount? ”)

Income>5*Principal&Income>25000

Unevaluated

Unevaluated

To qualify for a loan, a candidate must

Age=WASK(“Candidate’s age? ”)

have sufficient income, must be con-

Unevaluated

Stable is defined as being over 30 years

sidered stable, and must be an adult

old or married and having held the present

Qualify= Sufficient

job for 3 or more years

Married=WASKYN(“Is the candidate married? ”)

Income&Stable&Adult

Unevaluated

Stable=(Age>=30|Married)&Job Tenure>=3

Unevaluated

Unevaluated

Job Tenure=WASK(“Years in current job? ”)

Unevaluated

Adult is defined as being 18 or older

Age

Age=WASK(“Candidate’s age? ”)

Adult=Age>=18

Unevaluated

Unevaluated

Unevaluated

Source: Used with permission. DecisionPro™, Vanguard Software Corporation, www.vanguardsw.com.

122

T e c h n o l o g y

Inc., rules are created in a decision tree format, as show at the bottom of the exhibit. The end user sees a simple sequence of questions (top lef