Chapter 10

Storage of Hydrogen for Use as a Fuel1

NOTE: This module is based upon the Connexions course Methods of Hydrogen Storage for Use as a Fuel Case Study by Christian Cioce.

10.1 Introduction

Dihydrogen is a colorless and odorless gas at room temperature which is highly flammable, releasing a large amount of energy when combusted. As compared with combustion of the current fuels which operate automobiles, for example petrol or diesel, the energy released when hydrogen is combusted is more than three times greater. The heat of combustion for hydrogen is 141.9 kJ/mol as compared to 47.0 kJ/mol and 45.0 kJ/mol for gasoline and diesel, respectively.

Furthermore, the combustion of hydrocarbons releases the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO2) into the atmosphere, and is therefore not a "clean" fuel. When hydrogen is combusted in the presence of oxygen (from air) the only product is water, (10.1). Both its clean reactivity and the large chemical energy make H2 extremely appealing for use as a fuel in automobiles.

(10.1)

(10.1)

If hydrogen has such a potential as a fuel why has it not been widely implemented? Dihydrogen is a gas at room temperature. Gases, compared to the other states of matter (liquid and solid), occupy the most volume of space, for a given number of molecules. Octane and the other hydrocarbons found in gasoline are liquids at room temperature, demanding relatively small fuel tanks. Liquids are therefore easier to store than compressed gases.

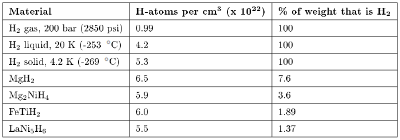

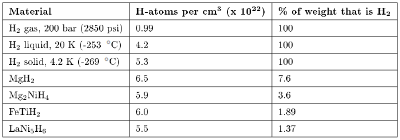

Hydrogen has a high energy content per weight (more than three times as much as gasoline), but the energy density per volume is rather low at standard temperature and pressure. Volumetric energy density can be increased by storing the gaseous hydrogen under increased pressure or storing it at extremely low temperatures as a liquid. Hydrogen can also be adsorbed into metal hydrides and highly porous materials (Table 10.1). The current available methods of storing hydrogen include compressed hydrogen and liquefied hydrogen, however many promising methods exist, namely metal organic materials (MOMs), metal hydrides and carbon nanostructures.

Table 10.1: Comparison of hydrogen storage ability of metal hydrides.

10.2 Liquid hydrogen

Liquid hydrogen is made possible by cryogenically cooling it to below its boiling point, -253 æC. As a liquid, the same amount of gaseous hydrogen will require much less volume, and therefore is feasible to individual automobile use. A refrigeration system is required to keep the liquid cooled, for if the system temperature rises above hydrogen's critical point (-241æC), the liquid will become a gas. There must exist a vacuum insulation between the inner and outer walls of liquid hydrogen tank system, for heat cannot travel through a vacuum. There is a tradeoff, however, because the tank must be an open system to prevent overpressure. This will lead directly to heat loss, though minimal.

The relative tank size has a broad range, with small tanks having a volume of 100 L, and large spherical tanks sizing all the way up to 2000 m3. Refrigeration systems are not a likely feature for every automobile, and open systems may pose a hazard should an accident occur. Cooling hydrogen down to a liquid is a convenient method of storage, however, and its implementation most likely will be limited to large stationary tanks as well as mobile multi-axle trucks.

10.3 Compressed hydrogen

Compressing gas is the process of applying an external force which minimizes the distance between gas particles, therefore forcing the system to occupy less volume. This is attractive since many particles can exist in a reasonably sized tank. At room temperature and atmospheric pressure, 4 kg of hydrogen occupies a volume of 45 m3, which corresponds to a balloon with a diameter of 5 m. Clearly compression is required to store and transport the gas. When it comes to individual mobility however, these tanks are still far too large for the average sized automobile.

Compressed tanks are regularly filled to 200 atmospheres in most countries. Storing 4 kg of hydrogen still requires an internal volume of 225 L (about 60 gallons). This amount can be divided into 5 tanks with 45 L internal volume.

10.4 Metal hydrides for storage

Metal hydrides are coordinated complexes and/or crystal systems which reversibly bind hydrogen. The hydrogen is favorably incorporated into the complex and may be released by applying heat to the system. A major method to determine a particular complex's effectiveness is to measure the amount of hydrogen that can be released from the complex, rather than the amount it can store (Table 10.1).

Some issues with metal hydrides are low hydrogen capacity, slow uptake and release kinetics, as well as cost. The rate at which the complex accepts the hydrogen is a factor, since the time to fuel a car should ideally be minimal. Even more importantly, at the current stage of research, the rate at which hydrogen is released from the complex is too slow for automobile requirements. This technology is still a very promising method, and further research allows for the possibility of highly binding and rapid reversal rates of hydrogen gas.

NOTE:

1This content is available online at <http://cnx.org/content/m32176/1.1/>.