Chapter 3

Synthesis of Molecular Hydrogen1

Although hydrogen is the most abundant element in the universe, its reactivity means that it exists as compounds with other elements. Thus, molecular hydrogen, H2, must be prepared from other compounds. The following outlines a selection of synthetic methods.

3.1 Steam reforming of carbon and hydrocarbons

Many reactions are available for the production of hydrogen from the reaction of steam with a carbon source. The choice of reaction is guided by the availability of raw materials and the desired purity of the hydrogen. The simplest reaction involves passing steam over coke at high temperatures (1000æC).

(3.1)

(3.1)

Coke is a grey, hard, and porous carbonaceous material derived from destructive distillation of low-ash, low-sulfur bituminous coal. As an alternative to coke, methane may be used at a slightly higher temperature (1100æC).

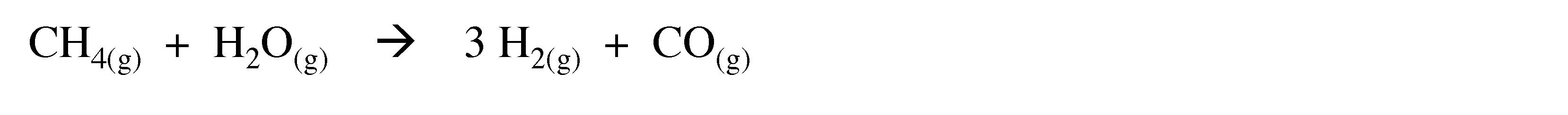

(3.2)

(3.2)

In each case the carbon monoxide formed in the reaction can react further with steam in the presence of a suitable catalyst (usually iron or cobalt oxide) to generate further hydrogen.

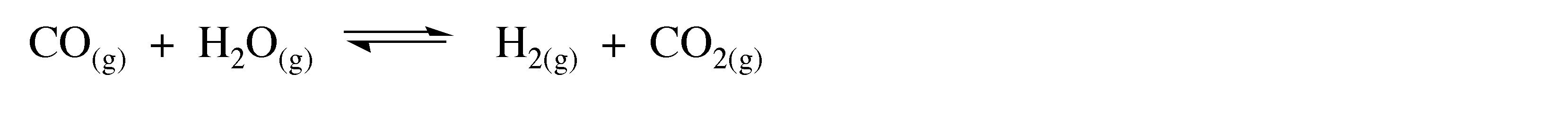

(3.3)

(3.3)

This reaction is known as the water gas-shift reaction, and was discovered by Italian physicist Felice Fontana (Figure 3.1) in 1780.

Figure 3.1: Italian physicist Felice Fontana (1730 - 1805).

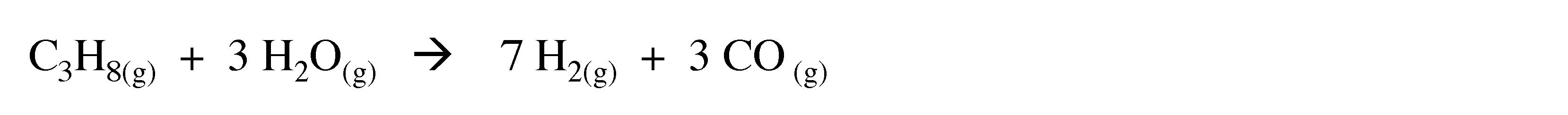

The dominant industrial process for hydrogen production uses natural gas or oil refinery feedstock in the presence of a nickel catalyst at 900æC.

(3.4)

(3.4)

3.2 Electrolysis of water

Electrolysis of acidified water in with platinum electrodes is a simple (although energy intensive) route to hydrogen.

(3.5)

(3.5)

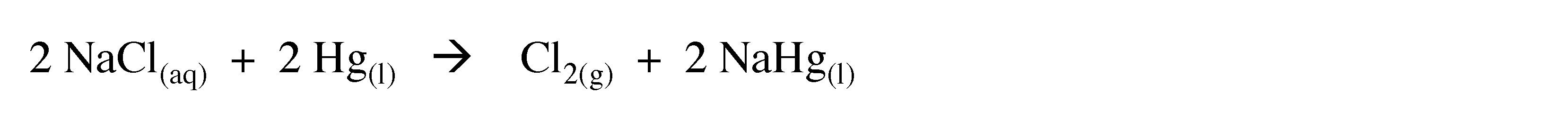

On a larger scale hydrolysis of warm aqueous solutions of barium hydroxide can yield hydrogen of purity greater than 99.95%. Hydrogen is also formed as a side product in the production of chlorine from electrolysis of brine (NaCl) solutions in the presence of a mercury electrode.

(3.6)

(3.6)

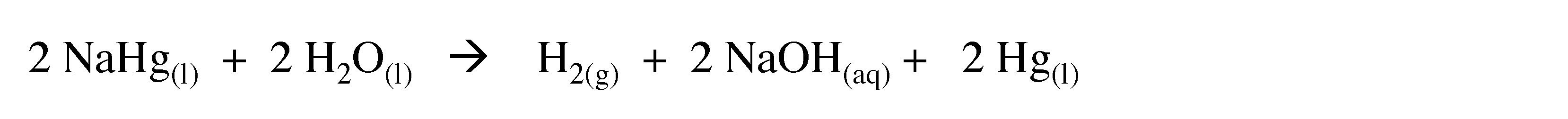

The sodium mercury amalgam reacts with water to yield hydrogen.

(3.7)

(3.7)

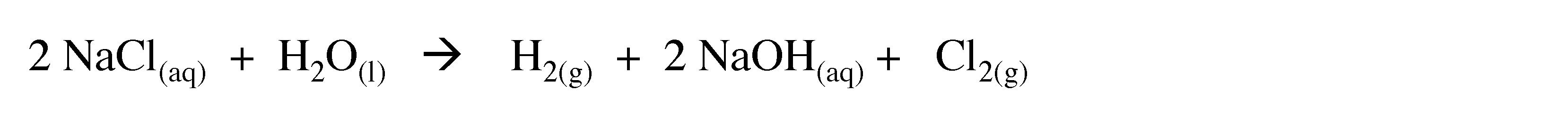

Thus, the overall reaction can be written as:

(3.8)

(3.8)

However, this method is being phased out for environmental reasons.

3.3 Reaction of metal with acid

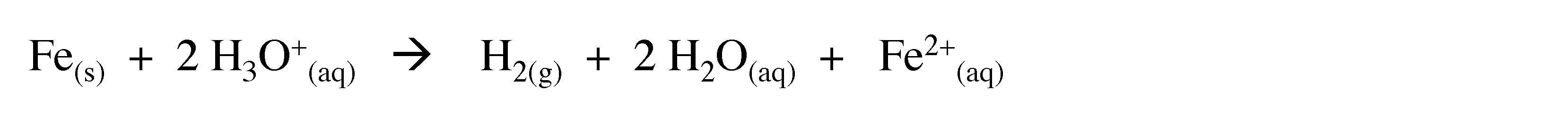

Hydrogen is produced by the reaction of highly electropositive metals with water, and less reactive metals with acids, e.g.,

(3.9)

(3.9)

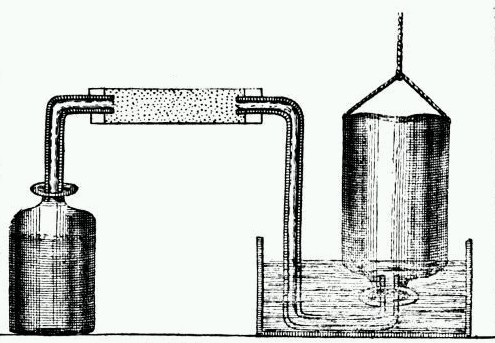

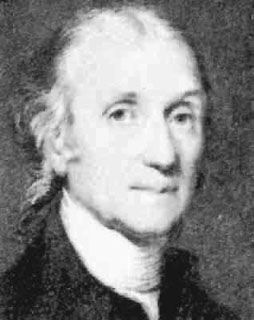

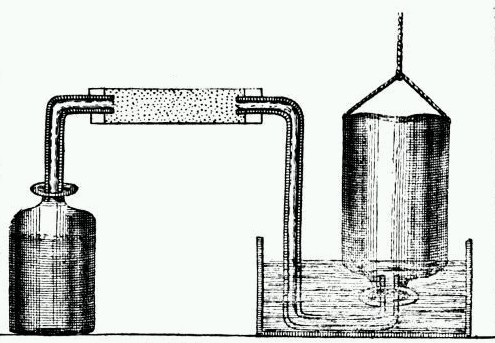

This method was originally used by Henry Cavendish (Figure 3.2) during his studies that led to the understanding of hydrogen as an element (Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.2: Henry Cavendish (1731 - 1810).

Figure 3.3: Cavendish's apparatus for making hydrogen in the left hand jar by the reaction of a strong acid with a metal and collecting the hydrogen gas above water in the right hand inverted jar.

The same method was employed by French inventor Jacques Charles (Figure 3.4) for the first ight of a hydrogen balloon on 27th August 1783. Unfortunately, terrified peasants destroyed his balloon when it landed outside of Paris.

Figure 3.4: Jacques Alexandre César Charles (1746 1823).

3.4 Hydrolysis of metal hydrides

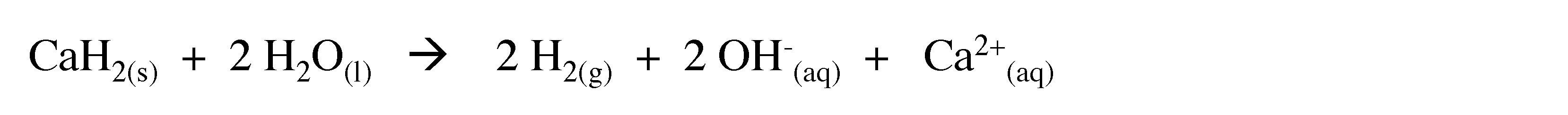

Reactive metal hydrides such as calcium hydride (CaH2) undergo rapid hydrolysis to liberate hydrogen.

(3.10)

(3.10)

This reaction is sometimes used to inflate life rafts and weather balloons where a simple, compact means of generating H2 is desired.

NOTES:

1This content is available online at <http://cnx.org/content/m31442/1.3/>.