Chapter 1. Gathering

The blank screen

You have an advertising assignment of some sort. If you’re sitting with a blank computer screen and struggling about what to do, stop. There’s a better way.

To start with, forget that daunting assignment for a while. Instead, gather facts that will interest and inform your audience. And hey, take it easy. This gathering process won’t stress you at all. Rather than grappling for the right words, you can turn the radio on, muse about good things, and – oh, yeah – collect information.

Best of all, fact-finding is the right thing to do at this stage. Ultimately, delivering advantages to the audience will produce more than pulling everything out of your head...or somewhere else.

FYI: Gathering is seen as a low-level chore, but that’s not true. Getting the nitty- gritty...

? Makes you knowledgeable, and this is essential to success

? Could give you the right strategy, appeal, idea – everything

The makings of a wonder worker

You’re probably told to generate stunning results on a small budget. And do it instantly.

It’s tempting to quit before you start. You think, “Nobody else has been able to advertise this product right. And now they want me to pull off a miracle in two months!”

On the contrary: You can put everything on the right course. You can deliver solid advertising that pulls in more responses, builds the image, and does more over the long term. But there are few miracles in the process. You have to mastermind and follow a creative advertising program that changes with necessity.

Where you are gathering from

In the dream world, you have researchers giving you jaw-dropping data about whatever you want. Needless to say, you can forget that. In the real world, it’s you, a pile of old product literature, some Websites, and a five-day deadline. But that’s fine. You’re a resourceful person, so you’ll rapidly uncover useful points that will help you create spellbinding ads.

Look through past company materials

This is the pile just mentioned, and it’s a tiptop source for product specifics.

Cut and paste like crazy. Place “features” into one group, “specifications” into another, “company background” into yet another, etc. Put together similar items, and if that group gets large, it will be worth considering. You’ll think of a category name for it.

In short, you tear apart the old, examine it, and reconstruct it the right way.

Notable: There are content experts in your organization. Don’t ask them to tell you everything you need, because they are too busy and valuable for that. Rather, ask them if they have any documentation you can read. They will say, “Sure!” and pile you up.

History of past campaigns

Your company’s previous marketing campaigns will help you a lot. Dig into the files of every significant marketing effort that took place within the last couple of years. Also, talk with those who were there. You can even contact former employees, because everyone remembers how well a campaign performed. They will be happy to help you, and they can lead you through the minefields.

When you look at an old campaign, you’re interested in the main points. For examples: Who was getting it? What was the message? What was the outcome? Campaigns rise or fall for profound reasons, not small ones.

What are you looking for?

You want anything interesting. This includes stuff that is relevant to the...

? Product’s

Value?

? Features

? Benefits

? Market’s

Needs?

? Characteristics

Keep theorizing as you go

Don’t reserve your judgment until the end of the collecting process. Keep thinking about what ad to create (this is what you’re ultimately doing, by the way) as you sift through the piles of everythings. Modify your assessments as you learn more.

Understanding the ununderstandable

Let’s say you’re reading gobbledygook technical literature, and you have

to get features and benefits out of it. If the text is in English (as opposed to chemical formulas, numeric tables or other confusifiers), there has to be something you can glean.

Go word? by word if you must.

Go into? your online dictionary and look up words.

There’s always a process, and it’s usually logical. Here are two examples of procedures you can look for:

1. Something goes into the product. That something is changed. And something else comes out.

2. The service they provide has a beginning, middle, and end to it.

You won’t figure everything out, but you’ll advance in the assignment. Then, when you talk with a content expert, you can say, “I learned the product does ABC. What I don’t get is XYZ. Could you explain XYZ to me?” It’s likely she’ll respond, “That’s a good question,” or, “We ask that question ourselves.” You arrived!

Also: When you learn many complex particulars, be happy. Few others will want to get as far as you.

Competitive materials

Your competition will give you a treasure trove of information, so invest a lot of time at their public Websites. To the smallest detail, you want to know what their product has and yours hasn’t, and vice versa. Put together side-by-side comparisons of features and benefits.

There is more in the “Competition” section on page 53. But right now, let’s talk about their public marketing materials. Review them, and you’ll start learning about what you should and shouldn’t advertise. It gets down to the basics: If the competing product has more standard features than yours, you won’t say, “We have the most standard features.”

Try out the product

Use it. You’ll add a new dimension to your thinking, and that could make all the difference.

Research

Embrace any advertising research you get, because you can learn a ton. It’s hard to say enough about the importance of research, since it can tell you all kinds of things that otherwise might never occur to you.

Statistics reveal the future

Statistics can be a tremendous help to you, because they clue you in on what is going to happen (maybe). Pay little attention to those who pay little attention to statistics. View the data and get the drift.

This means we need to look at data in big-picture ways.

Example? 1: There is not much difference between a 40% result and 50% result. For your purposes, they are about equal.

Example? 2: If the statistic says 10% of people do something, the real amount is probably not far off from that. Like, it’s not 80%. So, you know more than you did without the statistic.

Surveying surveys

You uncovered a survey. That’s cool, because it will tell you a lot! Now you can learn something. You should check out...

1. Who is giving the survey? That is least crucial.

2. Who is being surveyed? That is more crucial.

3. What are they surveyed about? That is most crucial. More on each of these:

1. Who is giving the survey? Don’t get sidelined by this. Thousands of studies are conducted by industry publications – not by independent testing labs in Iowa. Most publication surveys are ultimately geared to promote their magazine or Web-based information source, but be happy. Their reports are straightforward. Also, you’re examining narrow slices of your market, and there probably won’t be other free data. Also, their reports are 99% straightforward. You should learn the market’s...

? Characteristics

? Interest

Trends? in the market

Trends?

Size?

You can easily spot the questions put in to hype the publication. For example: “If you had a daily news e-mail that delivered immediate news about hot topics critical to your success, would you read it?” And 92% said yes!

2. Who is being surveyed is basic. You would like people who match your market’s profile, or have some relation to what you’re doing.

3. What they are surveyed about is what you care about! As long as the questions don’t raise their defenses, people will give introspective answers. And you’ll be clued in.

Judgment over research

Unfortunately, coworker Notman Agingit gloms onto data because it’s data. “It’s obvious what we should do,” he says. “Because the research tells us.” He turns his mind off and lets a study manage the campaign.

Don’t do this! The research data should only be your assistant. The real star is...(drum roll)...Your Insightful Mind.

What’s in your head is almost always best. For example, if your product is sold in extended care facilities, imagine being in an extended care facility. How would it be to live there? To work there? Rely on what you think up far more than what the research tells you. Read more on this in “The Jump-In method” on page 38.

It’s not easy to make your case

When you put the most trust in your insights (that’s what we did in the last subsection), some people won’t understand. And it can be a trialing experience.

Attorney: In your ad, why did you tell the market what you did?

You: It was a feeling I had.

Attorney: A feeling. So, none of your potential customers said this is what they wanted?

You: No one, no.

Attorney: Indeed, according to this focus group report, prospects were telling you something completely different from what you decided to do. Isn’t that true?

You: Yes, but I didn’t think the people in the focus group were expressing their true feelings. I still don’t.

Loud court murmur.

In short, your job isn’t to rubber stamp “OK” to what the research says. Factor that data into your perceptive decision.

Reference: “Latch on illogically,” on page 97.

cLet’s say you’re assigned to market fabric to consumers, and you

know little about cloth. You can at least think, “Lots more women will buy this fabric than men.” It’s beyond dispute.

Despite this, coworker Solex Ample says, “My Uncle Lircaw buys a lot of fabric, so I think we should market to men as well.” Hmph. Lex, your uncle is an exception, and you shouldn’t let his situation dominate your judgment.

If Solex presses the issue, ask him this: “What do you think is the percentage of men who buy fabric?” Solex might respond, “I have no

idea. Maybe we should do a study. Sol, there’s no time for that! The fact is: You’re paid to make strong assessments when you have scant information. So, please: Use some common sense now.

Above all, don’t let screwball opinions stop your progress. It’s serious. If you follow people who have zero marketing sense, the advertising will fail.

Market research vs. time

Performing lots of research can put you into a difficult situation, because three critical months are spent studying, and there are no responses (a.k.a. leads, replies, orders, inquiries) coming in. You can’t say you have the answer because you don’t. Instead, you need to let the market begin telling you the answers. Learn more about this in “Trialing reigns,” on page 19.

Reference: “Can’t keep gathering,” on page 18.

Inside

Talk with coworkers

They’re all around you and they know a lot. It’s time to get some sage advice from them.

Be humble in your pursuit

A detective doesn’t claim to have the case solved before she comes on the scene, and you shouldn’t either. So, never act like the #1 Advertising Guru. Say this instead: “I don’t have all the answers now. I only have questions. We won’t know for a while.”

Relatedly, it may be tempting to isolate yourself in this process…to give this impression: “I’m the brooding genius – don’t bother me.” However, it’s a smarter genius who brings coworkers into the process. Two reasons (aside from the usual ones):

1. Coworkers help you cut through the bull.

2. Coworkers get complaints about marketing off their chests. You’ll hear them say, “If you ask me, we don’t do enough...” And, “We’ve been doing that the wrong way.” Take their thoughts seriously.

Setup for the interview

Who, what, when, where, why and how

Also known as 5Ws&H, these question words put you on the fast track to getting information. You want to know who the market is, what the product does, when people buy, etc.

5Ws&H help you every time. Let’s say one of the content experts has time to answer your questions...but you haven’t written any. No panic. Simply jot on your yellow notepad, “who, what, etc.” The questions will start jumping out of you: “Who, in your view, is this product for?” Then enjoy the learning experience.

Lotsa notes

When your content expert dives deep into the subject, you could space out (OK, you will space out) and lose track of the discussion. Taking voluminous notes won’t keep your mind from wandering, but it gives you something to reference when the expert finishes and awaits the next question. “Oh!” you awaken and exclaim. You glance look at your notes, then read-and-repeat what he last said. Simultaneously, another question comes to you. You’re saved.

Short point: Learn how to write quickly/illegibly, because you’ll pick up more facts. Type up your notes right after the meeting, and your memory will fill in the unreadable spots.

Ask dumb questions. Really

A content expert will speak about something for 30 minutes. Then you’ll ask, “I’m sure I should know this, but what is that [basic item] you spoke about?” Watch his mouth drop to the floor. He says with his eyes, “We all know that! How could you be in this organization and not know that?”

Oh, well. Some believe you have to know everything before you can learn anything. This is wrong, of course. You’re putting together a jigsaw puzzle, and you’ll start to get the picture before some essential sections are together. You ask basic questions to help complete the image.

Relatedly, if you spend your time trying to impress the experts, 1) you won’t learn anything, 2) you won’t impress them, and 3) you won’t turn out valuable ads. Ask whatever you think will shed light, and let people wonder how a confused marketer gets such awesome results.

Still, you should not say, “I never understand what they’re talking about around here!” That’s inviting trouble, because you’re really saying, “I’m ignorant and I think it’s funny.” This won’t help you. Instead, when cornered on the “how much do you know?” question, here is your reply: “I’m always learning around here.” Nobody would respond, “I’m not learning. I know everything already.”

Question obscure terms

Oodles of terms used within an industry (a.k.a. lingo) find their way into the marketing literature, but you don’t know if your market knows them. So, for example, you ask coworkers: “Is our audience familiar with Luddism?” About 20% of the time you’ll discover that your market isn’t familiar, and it’s good you checked.

Managing the interview

You’ll learn bunches from your interviews with content experts.

However, unless you’re steering the conversation correctly, it can bog down with discussions that have little to do with your goal.

Oh, and here is the goal: To discover pertinent details – stuff that will attract the market.

This is what you do: While the expert is speaking, filter it silently. Ask yourself, “Does my market care about what this expert is saying?” If the answer is no, think: “What would my market care about?” Then steer the conversation in that direction. In other words, ask questions that help you understand how and why this product is right for the market.

What understanding did you get?

Well?

The hidden drama

A heckuva lot goes into your product. There are little-known

fascinatingnesses in the...

Thought? behind it

Battle? for it

Design? of it

? Components in it

? Manufacture of it

Quality? control with it

Content experts know the tiny details. Therefore, inquire of the expert: “What are some interesting things that few people know about the product?”

Talk with salespeople

Many inside scoops come from the sales department. These folks work on the front lines every day, and they will give you mind-boggling information about what moves buyers.

For example: A statistic tells you that 35% of your product purchases are in California. That’s fine...but why so much? You ask a salesperson and she replies, “There’s a lot of military in California.” Interesting. Maybe you could do something with this in the advertising.

Learning outside the company

Talk with prospects

To learn about the prospects, speak to them. Sounds obvious? Sure, but some marketers find it too bothersome to talk with prospects. They’d rather draw conclusions from inane TV shows that satirize, romanticize, or characterize the prospects. (As a rule of thumb, TV presents the wrong perspective of every group.) In short, some creative people don’t want to learn what is beyond their remote controls.

There is no reason for this, because interviewing prospects is easy. Contact a potential customer and ask open-ended questions, like, “What are you looking for?” Write down his words verbatim. He will give you new perspectives, and it will only cost some e-mails and phone calls.

Reference: “prospect as a friend,” on page 37.

Contact experts from your past

Let’s say you have a new writing assignment, and you need to know a lot about the chemical elements...like Au and the H and O from H2O. Since you barely got through chemistry in high school, you aren’t going to rely on your own knowledge.

Solution: Go out to Websites pertaining to your subject (not the corporate sites, but the “I’m so wild about chemistry I built this site” sites). Send out five "can you help me?" e-mails to the sites’ gurus and you should get two replies. You’ll learn what you need to know without rummaging through piles of research books. And you'll make a great new online friend.

Reference excellent work

The CIA’s tactics are secret, making it difficult for competing intelligence operations to learn them. However, you can see terrific advertising tactics by looking at magazines, Websites, TV commercials, and direct mail pieces. Let that outstanding output inspire you.

Challenge: Be at least as good as the best.

Also: If you were expecting a little ha-ha line about the CIA, sorry. This book is too chicken.

Can’t keep gathering

Gathering is splendid. But it has to end now, because everyone is waiting for you to make accomplishments. Solutions need to fly out of you, because...

Long? research hours aren’t budgeted

The? deadline is approaching

The? facts you collect become repetitive

There? are other assignments

Everything will fall apart if you hesitate at any point in this process. The responses won’t come in, the salespeople won’t have materials, and the organization will lose confidence in you. Yu dunt wunt this.

Advice: Work so fast that coworkers say you hit the ground running on the advertising assignment, and it’s well on the way. This will avoid doubts and other unhappinesses.

Profiling those who delay

For gosh sake, don’t be like those who walk around the project. They drag their feet, and then blame everyone else when deadlines are missed.

Don’t? call meetings two weeks out and wait to act until then. Instead, set up a quick teleconference.

Don’t? say you must hold on ad creation until the new product is complete. Get started and fill in the blanks later.

Don’t? set up on-site research at some remote place. Wing it.

In a word, charge!

Here are two reasons some advertisers lollygag:

1. They don’t trust their own judgment enough to act on it. But your judgment is excellent, so worry not. If you have uncertainties, don’t fret. Experimenting with different approaches (something we're going to do) should resolve everything. You’ll let the market determine what it wants, and you’ll earn responses in the meantime. Reference: “Trialing reigns,” on page 19.

2. They are unwilling to put in the extra hours necessary to make early accomplishments. It’s a well-known fact that ad creation consumes a lot of time, so they need to adjust.

Yours is better by three months

Coworker Ignor Dudate says, “I guess it’s good you got the ads out there when you did, but you should have performed more research first.”

Your reply: “Nev, our ads are getting the ultimate research: The market is judging them, and we’re learning by counting the responses that come in. In other words, we’re determining what the market wants, and we’re generating leads while we're at it. All this beats the traditional notion of research.”

In short, it’s called: “Earn while you learn.”

Experimenting

The spectacular failure

Advertiser Cap Tainsmith decides to put a titanic effort behind one new concept. He declares: “This will be the largest campaign we’ve ever done!” Developing it takes months longer than anticipated. Sales leads aren't coming in. Opportunities are missed. Still, Cap is certain this enormous new campaign will float. It has to.

Nevertheless, it sinks. This is because Cappy didn't...

Quickly? get the advertising into the market

Let the? market tell him what it wanted

Make? adjustments accordingly

Bad campaign? Don’t count on repetition

Some advertisers believe that a strong budget can force a weak ad onto the market. This wasteful strategy fails way too often.

Of course, repetition can make a strong ad sink in. You pound the message lots of times, the audience finally understands, and responds. Reference: “Lather, rinse, repeat,” on page 127.

Rule of thumb: A sensational ad with a poor budget does better than a poor ad with a sensational budget.

Trialing reigns

Instead of risking a major disaster, trial. When you trial, you run different types of advertising, measure the replies, and determine your next course of action. This way, the market tells you what to do.

Here is a simple way to trial. It’s called a “split run test.” You...

Come up? with three different approaches

Turn? them into three direct response pieces

Put a? different response code number onto each piece

Mail? them to similar groups

Count? the responses

Make? future moves based upon what you learn

Testing continues as you expand and sharpen your efforts.

You can also perform split runs with broadcast e-mail campaigns, Internet vehicles and many print magazines.

Bottom line: Ultimately, it all comes down to trial and error.

Select response-oriented media

A key to all this is measuring responses. You’re seeing how you’re doing as you move along. In order to accomplish this, you need to advertise in places that deliver quantifiable data about the results. Otherwise, the advertising will always be seen as an expense – one that can be cut when times get tough.

You’re purchasing leads and customers

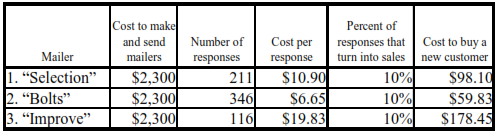

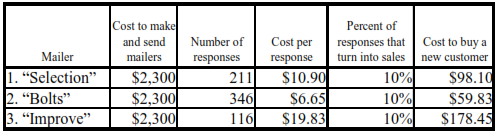

You want to say, “We’re not spending money on advertising. We’re purchasing sales leads and new customers.” Here is a way to tabulate these purchases. It is a comparison of three different mailers.

As you see what works the best (“Bolts” is a real winner), you can ramp it up. Send the mailer to more people, and buy more customers for less money.

Advancing before all the results are in

Typical trialing (like the kind you just read about) isn’t practical in

most cases, probably because:

You’re? advertising in a medium that doesn’t allow split runs.

You’re? moving swiftly, and you can’t wait for indicators.

The solution is to leapfrog.

Leapfrogging

The best way to explain leapfrogging is with an example. Let’s say it’s November 20, and you have to place magazine insertions. You decide to create three distinct ads, and run...

? Approach 1 in the January issue

? Approach 2 in the February issue

? Approach 3 in the March issue

Now it’s February 12, so you’re counting responses from the January and February insertions. Also, you’ve already committed Approach 3 for March. The question is: What should you run in April?

You thought the January approach would deliver loads of responses (that’s why you ran it first), but it brought in only a handful. However, your February ad is showing promise.

For April, and you decide to rerun Approach 2. Therefore, that promising February ad is leapfrogging over March and going into April. Also, it will probably become the basis for your long-term campaign. But the March ad could still become your best performer.

Some points about leapfrogging:

Rather? than running one approach for three months and risking having a three-time loser, you’re giving yourself three opportunities to succeed.

This? method gives you more time to work up those ads. The March ad didn’t have to be completed until two months after the January ad

– thank goodness. If you did a split-run and produced three ads at the same time, that would have been a triple burden. Also, if a person is unhappy with the tone in the January ad, you can reply, “I'll make sure our next ad doesn't come across that way.”

Jumpstarting a comprehensive campaign

It would be wonderful if we had time to experiment with approaches.

However, throughout life you’ll have few opportunities to trial. Maybe you’ll need a new image for an upcoming trade show. Maybe you’ll only have three weeks to launch a campaign for the crucial selling season. Whatever. Most times, you have one chance, and it has to produce.

You can pull this off, and here is how. You run different ads that…

Promote? different appeals

Keep a? similar visual theme

For example, you decide upon an auto-racing theme. You create three ads with one overall visual (racecars) and three different messages:

1. Power. Show racecar being fueled.

2. Speed. Show one car overtaking another.

3. Control. Show hand on a gearshift.

Run the ads, count the responses from each, and figure that one of these messages will outpace the others. Then, shift the direction of your campaign toward that message. Also, if one of the three ads has a weak response, don’t fret. It still contributed to your overall racing theme.

Reference: “Let’s build a campaign,” on page 84.

The world’s fastest pretest

Before you finalize those three ads, e-mail them to prospective customers and ask, “What do you think of these?” People enjoy being asked, and you’ll learn a lot.

Assessing responsibility for success or failure

You run ads and send out direct mailers, and you achieve success. All right! The question is: What made the campaign a winner – the ads or the mailers...or the PR...or the word of mouth?

When there are several factors, it’s difficult to pinpoint what is responsib