6 Putting It All Together

Agroecology — the science that underlies sustainable farming — integrates the conservation of biodiversity with the produc- tion of food. It promotes diversity which in turn sustains a farm’s soil fertility, productivity and crop protection.

Innovative approaches that make agriculture both more sustainable and more productive are flourishing around the world. While trade-offs be- tween agricultural productivity and biodiversity seem stark, exciting op- portunities for synergy arise when you adopt one or more of the following strategies:

-

Modify your soil, water and vegetative resource management by limit- ing external inputs and emphasizing organic matter accumulation, nutrient recycling, conservation and diversity.

-

Replace agrichemical applications with more resource-efficient meth- ods of managing nutrients and pest populations.

-

Mimic natural ecosystems by adopting cover crops, polycultures and agroforestry in diversified designs that include useful trees, shrubs and perennial grasses.

-

Conserve such reserves of biodiversity as vegetationally rich hedge- rows, forest patches and fallow fields.

-

Develop habitat networks that connect farms with surrounding eco- systems, such as corridors that allow natural enemies and other ben- eficial biota to circulate into fields.

Different farming systems and agricultural settings call for different combinations of those key strategies. In intensive, larger-scale cropping systems, eliminating pesticides and providing habitat diversity around field borders and in corridors are likely to contribute most substantially to biodiversity. On smaller-scale farms, organic management — with crop rotations and diversified polyculture designs — may be more appropriate and effective. Generalizing is impossible: Every farm has its own particular features, and its own particular promise.

Designing a Habitat Management Strategy

The most successful examples of ecologically based pest management sys- tems are those that have been derived and fine-tuned by farmers to fit their particular circumstances. To design an effective plan for successful habitat management, first gather as much information as you can. Make a list of the most economically damaging pests on your farm. For each pest, try to find out:

-

What are its food and habitat requirements?

-

What factors influence its abundance?

-

When does it enter the field and from where?

-

What attracts it to the crop?

-

How does it develop in the crop and when does it become economi- cally damaging?

-

What are its most important predators, parasites and pathogens?

-

What are the primary needs of those beneficial organisms?

-

Where do these beneficials over-winter, when do they appear in the field, where do they come from, what attracts them to the crop, how do they develop in the crop and what keeps them in the field?

-

When do the beneficials’ critical resources — nectar, pollen, alterna- tive hosts and prey — appear and how long are they available? Are alternate food sources accessible nearby and at the right times? Which native annuals and perennials can compensate for critical gaps in tim- ing, especially when prey are scarce?

-

See Resources p. 104 and/or contact your county extension agent to help answer these questions.

The examples below illustrate specific management options to address specific pest problems:

-

In England, a group of scientists learned that important beneficial predators of aphids in wheat over-wintered in grassy hedgerows along the edges of fields. However, these predators migrated into the crop too late in the spring to manage aphids located deep in the field. After the researchers planted a 3-foot strip of bunch grasses in the center of the field, populations of over-wintering predators soared and aphid damage was minimized.

-

Many predators and parasites require alternative hosts during their life cycles. Lydella thompsoni, a tachinid fly that parasitizes European corn borer, emerges before corn borer larvae are available in the spring and completes its first generation on common stalk borer in- stead. Clean farming practices that eliminate stalk borers are thought to contribute to this tachinid fly’s decline.

-

Alternative prey also may be important in building up predator num- bers before the predator’s target prey — the crop pest — appears. Lady beetles and minute pirate bugs can eventually consume many European corn borer eggs, but they can’t do it if alternative prey aren’t available to them before the corn borers lay their eggs.

-

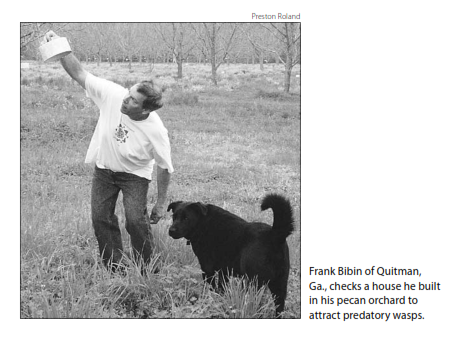

High daytime soil temperatures may limit the activity of ground- dwelling predators, including spiders and ground beetles. Cover crops or intercrops may help reduce soil temperatures and extend the time those predators are active. Crop residues, mulches and grassy field borders can offer the same benefits. Similarly, many parasites need moderate temperatures and higher relative humidity and must escape fields in the heat of day to find shelter in shady areas. For example, a parasitic wasp that attacks European corn borers is most active at field edges near woody areas, which provide shade, cooler temperatures and nectar-bearing or honeydew-coated flowering plants.

Enhancing Biota and Improving Soil Health

Managing soil for improved health demands a long-term commitment to us-

ing combinations of soil-enhancing practices. The strategies listed below can

aid you in inhibiting pests, stimulating natural enemies and — by alleviating

plant stress — fortifying crops’ abilities to resist or compete with pests.

-

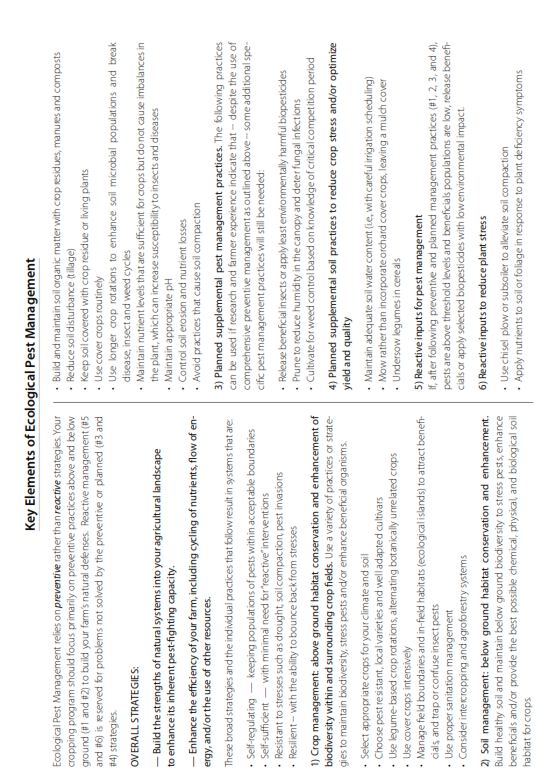

Add plentiful amounts of organic materials from cover crops and other crop residues as well as from off-field sources like animal manures and composts. Because different organic materials have different effects on a soil’s biological, physical and chemical properties, be sure to use a vari- ety of sources. For example, well-decomposed compost may suppress crop diseases, but it does not enhance soil aggregation in the short run. Dairy cow manure, on the other hand, rapidly stimulates soil aggregation.

-

Keep soils covered with living vegetation and/or crop residue. Residue protects soils from moisture and temperature extremes. For example, residue allows earthworms to adjust gradually to decreasing tempera- tures, reducing their mortality. By enhancing rainfall infiltration, resi- due also provides more water for crops.

-

Reduce tillage intensity. Excessive tillage destroys the food sources and micro-niches on which beneficial soil organisms depend. When you reduce your tillage and leave more residues on the soil surface, you create a more stable environment, slow the turnover of nutrients and encourage more diverse communities of decomposers.

-

Adopt other practices that reduce erosion, such as strip cropping along contours. Erosion damages soil health by removing topsoil that is rich in organic matter.

-

Alleviate the severity of compaction. Staying off soils that are too wet, distributing loads more uniformly and using controlled traffic lanes — including raised beds — all help reduce compaction.

-

Use best management practices to supply nutrients to plants without polluting water. Make routine use of soil and plant tissue tests to de- termine the need for nutrient applications. Avoid applying large doses of available nutrients — especially nitrogen — before planting. To the greatest extent possible, rely on soil organic matter and organic amendments to supply nitrogen. If you must use synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, add it in smaller quantities several times during the season. Once soil tests are in the optimal range, try to balance the amount of nutrients supplied with the amount used by the crops.

-

Leave areas of the farm untouched as habitat for plant and animal diversity.

Individual soil-improving practices have multiple effects on the agro- ecosystem. When you use cover crops intensively, you supply nitrogen to the following crop, soak up leftover soil nitrates, increase soil organisms and improve crop health. You reduce runoff, erosion, soil compaction and plant- parasitic nematodes. You also suppress weeds, deter diseases and inoculate future crops with beneficial mycorrhizae. Flowering cover crops also harbor beneficial insects.

Strategies for Enhancing Plant Diversity

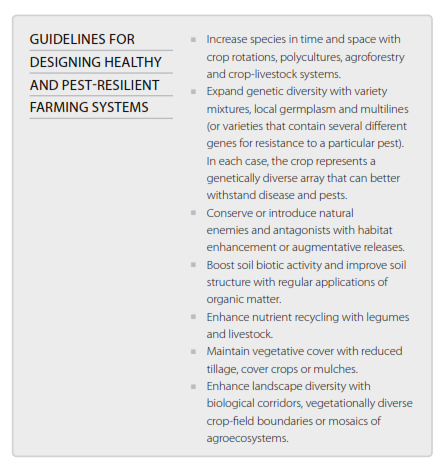

As described, increasing above-ground biodiversity will enhance the natu- ral defenses of your farming system. Use as many of these tools as possible to design a diverse landscape:

-

Diversify enterprises by including more species of crops and livestock.

-

Use legume-based crop rotations and mixed pastures.

-

Intercrop or strip-crop annual crops where feasible.

-

Mix varieties of the same crop.

-

Use varieties that carry many genes — rather than just one or two — for tolerating a particular insect or disease.

-

Emphasize open-pollinated crops over hybrids for their adaptability to local environments and greater genetic diversity.

-

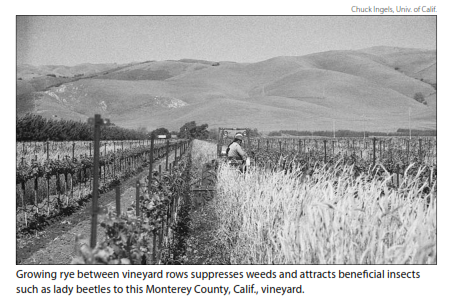

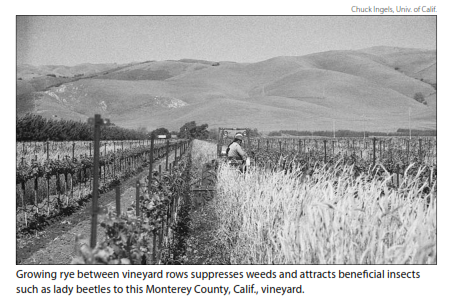

Grow cover crops in orchards, vineyards and crop fields.

-

Leave strips of wild vegetation at field edges.

-

Provide corridors for wildlife and beneficial insects.

-

Practice agroforestry, combining trees or shrubs with crops or live- stock to improve habitat continuity for natural enemies.

-

Plant microclimate-modifying trees and native plants as windbreaks or hedgerows.

-

Provide a source of water for birds and insects.

-

Leave areas of the farm untouched as habitat for plant and animal di- versity.

As you work toward improved soil health and pest management, don’t concentrate on any one strategy to the exclusion of others. Instead, combine as many strategies as make sense on your farm. Nationwide, producers are finding that the triple strategies of good crop rotations, reduced tillage and routine use of cover crops impart many benefits. Adding other strategies — such as animal manures and composts, improved nutrient management and compaction-minimizing techniques — provides even more.

Rolling out your Strategy

Once you have a thorough knowledge of the characteristics and needs of key pests and natural enemies, you’re ready to begin designing a habitat- management strategy specifically for your farm.

-

Choose plants that offer multiple benefits — for example, ones that improve soil fertility, weed suppression and pest regulation — and that don’t disrupt desirable farming practices.

-

Avoid potential conflicts. In California, planting blackberries around vineyards boosts populations of grape leafhopper parasites but can also exacerbate populations of the blue-green sharpshooter that spreads the vinekilling Pierce’s disease.

-

In locating your selected plants and diversification designs over space and time, use the scale — field- or landscape-level — that is most consistent with your intended results.

-

And, finally, keep it simple. Your plan should be easy and inexpensive to implement and maintain, and you should be able to modify it as your needs change or your results warrant.

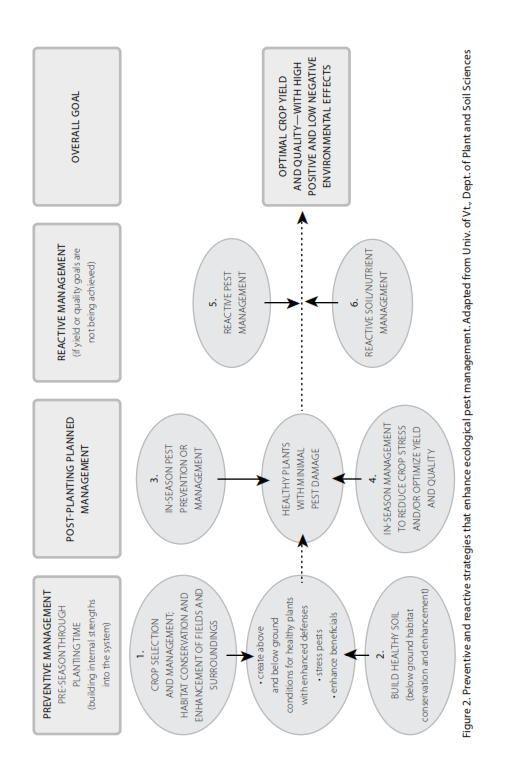

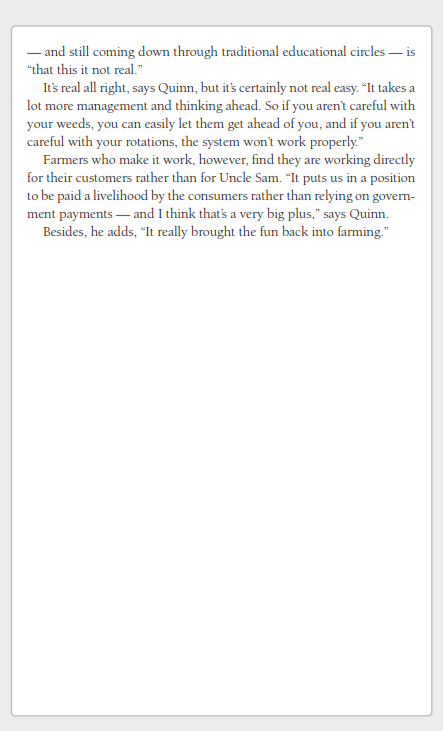

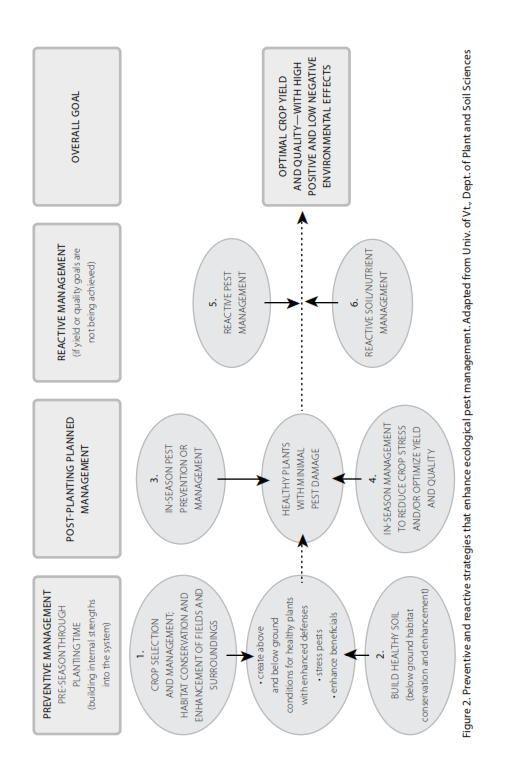

In this book, we have presented ideas and principles for designing and implementing healthy, pest-resilient farming systems. We have explained why reincorporating complexity and diversity is the first step toward sus- tainable pest management. Finally, we have described the pillars of agro- ecosystem health (Figure 1, p. 9):

-

Fostering crop habitats that support beneficial fauna

-

Developing soils rich in organic matter and microbial activity

Throughout, we have emphasized the advantages of polycultures over monocultures and, particularly, of reduced- or no-till perennial systems over intensive annual cropping schemes.

Universal Principles, Farm-Specific Strategies

The key challenge for farmers in the 21st century is to translate the prin- ciples of agroecology into practical systems that meet the needs of their farming communities and ecosystems. You can apply these principles through various techniques and strategies, each of which will affect your farm differently, depending on local opportunities and resources and, of course, on markets. Some options may include both annual and perennial crops, while others do not. Some may transcend field and farm to encom- pass windbreaks, shelterbelts and living fences. Well-considered and well- implemented strategies for soil and habitat management lead to diverse and abundant — although not always sufficient — populations of natural enemies.

As you develop a healthier, more pest-resilient system for your farm, ask yourself:

-

How can I increase species diversity to improve pest management, compensate for pest damage and make fuller use of resources?

-

How can I extend the system’s longevity by including woody plants that capture and recirculate nutrients and provide more sustained support for beneficials?

-

How can I add more organic matter to activate soil biology, build soil nutrition and improve soil structure?

-

Finally, how can I diversify my landscape with mosaics of agroecosys- tems in different stages of succession?

Because locally adapted varieties and species can create specific genetic resilience, rely on local biodiversity, synergies and dynamics as much as you can. Use the principles of agroecology to intensify your farm’s effi- ciency, maintain its productivity, preserve its biodiversity and enhance its self-sustaining capacity.