PEKIN.

[Pg 273]

The winter of 1860-61 Madame de Bourboulon spent quietly at Tien-tsin, her health not permitting her, in such rigorous weather, to make the journey to Pekin; but on the 22nd of March the whole legation set out for the Chinese capital, Madame de Bourboulon travelling in a litter, attended by her physician. Fortunately, the change of air and scene, and the easy movement gradually restored her physical energies. From Tien-tsin to Pekin the distance is about thirty leagues. On the road lies Tchang-kia-wang, the scene of the treacherous outrage in 1858 on the French and English bearers of truce; and almost at the gates of Pekin, the great town of Tung-tcheou and the famous bridge of Palikao, where, on the 21st of September, 1860, the Anglo-French army defeated 25,000 Tartar horsemen. This bridge, a curious work of art, measures one hundred and fifty yards in length and thirty in breadth; the marble balustrades are skilfully carved, and surmounted by marble lions in the Chinese taste.

On arriving at Pekin the French embassy was installed in the Tartar quarter. Five months later the revolution broke out which placed Prince Kung in power. The prince was well-disposed towards Europeans, and under his rule Madame de Bourboulon was able to traverse Pekin without fear. We subjoin some extracts from her journals:—

"I set out on horseback this morning," she says,

[Pg 274]

"accompanied by Sir Frederick Bruce and my husband, to make a tour of the Chinese town; our escort consisted only of four European horsemen and two Ting-tchaï. We arrived at a populous carrefour, which derived a peculiar character from the large numbers of country people who flock there to dispose of all kinds of provisions, but particularly, game and vegetables; heaps of cabbages and onions rise almost to the height of the doors of the houses.

"The peasants, seated on the ground, smoke their pipes in peace, while the aged mules and bare-skinned asses, which have conveyed their wares, wander about the market-place, gleaning here and there some vegetable refuse.

At every step the townsfolk, with indifferent bearing, and armed with a fan to protect their wan and powdered complexion, jostle against the robust copper-coloured country people, whose feet are thrust into sandals, and their heads covered with large straw hats. Not knowing how to guide our horses through the midst of this confused mob, we gained the precincts of the police pavilion in the hope of enjoying a little more tranquillity.

"We had been there a few moments only, when my horse showed a determined unwillingness to remain. Evidently something had frightened him. I raised my head mechanically, and thought I should have fainted before the horrible spectacle which struck my eyes. Behind us, close at hand, was a row of posts to which were fixed cross-beams of wood, and in each cage were

[Pg 275]

death's heads, which stared at me with fixed, wide-open eyes, their jaws dislocated with frightful grimaces, their teeth set convulsively by the agony of the last moment, and the blood rolling drop by drop from their freshly severed necks!

"In a second we had spurred our horses to the gallop to get out of sight of this hideous charnel-house, of which I long continued to think in my sleepless nights.

"Turning to the left, we entered a street which I will call, in allusion to the trade of its inhabitants, the Toymen's....

But what means this noisy music, this charivari of flutes and trumpets, drums, and stringed instruments? It is a funeral ceremony, and yonder is the door of the defunct, and in front of it the Society of Funerals (there is such an one at Pekin) has raised a triumphal arch, consisting of a wooden framework, covered with old mats and pieces of stuffs. The family has stationed a band at the door to proclaim its grief by rending the ears of the passers-by.

"We quicken our steps in order to avoid being delayed in the middle of the interminable procession. The gala-day in a Chinaman's life is the day of his death. He economizes, he deprives himself of all the comforts of life, he labours without rest or intermission, that he may have a fine funeral!

"We do not get out of this accursed street! Here another large crowd bars our passage; some proclamations and notices have just been placarded on the door of the chief of the district police; people are reading

[Pg 276]

them aloud; some declaim them in a tone of bombast; while a thousand commentaries, more satirical than the text, are uttered amidst loud bursts of laughter.

"This liberty of mockery, pasquinade, and caricature at the expense of the mandarins is one of the most original sides of Chinese manners.

"A band of blind beggars, in a costume more than light, pass along, hand in hand; then an itinerant smith, a barber al fresco, and a cheap restaurateur, simultaneously ply their different trades surrounded by their customers.

"We dismounted from our horses, and by a covered passage or arcade proceeded on foot to the legation. This passage, much favoured by vendors of bric-à-brac, is simply a dark lane, 550 to 600 feet long, where two people can hardly walk abreast. There are no proper shops here, but collections of old planks, united anyhow, and supported by piles of merchandise of all kinds, vases, porcelain, bronzes, arms, old clothes, pipes; from the whole proceeds a fœtid and insupportable odour, tempered by the thick pungent smoke of lamps fed with rice-oil.

"The reader may judge with what pleasure we regained the pure air, the blue sky, and all the comfortable appliances of our quarters at Tsing-kong-fou."

Having made the journey from China to Europe five times by sea, Madame de Bourboulon and her husband resolved that their sixth should be by land, being

[Pg 277]

desirous of rendering some direct service to science by penetrating into regions of which little was known. This overland route, as they foresaw, would involve them in many difficulties, fatigues, and hardships. It would impose on them a journey of six thousand miles, in the midst of half-savage populations, and over steppes and deserts virtually pathless; they would have to climb steep mountain-sides, to ford broad rivers; and, finally, to sleep under no better roof than that of a tent, and to live on milk, butter, and sea-biscuit for several months. Madame de Baluseck, wife of the Russian minister at Pekin, had already accomplished this journey. Madame de Bourboulon felt capable of an equal amount of courage, and though accustomed to live amid all the luxuries and comforts of European civilization, desired to encounter these privations, and to brave these perils.

Prince Kung, regent of the Chinese Empire, promised the travellers full security as far as the borders. He did more; for he attached to their train some mandarins of high rank to ensure the execution of his orders. A fortnight before the day fixed for departure, a caravan of camels was despatched to Kiakhta, on the Russian frontier, with wine, rice, and all kinds of provisions, intended to replace the supplies which would necessarily be exhausted during the transit of Mongolia.

A captain of engineers, M. Bouvier, superintended the construction of some vehicles of transport, light enough to be drawn by the nomad horsemen, and yet

[Pg 278]

solid enough to bear the accidents of travel in the desert. Bread, rice, biscuit, coffee, tea, wine, liqueurs, all kinds of clothing, preserved meats and vegetables, were carefully packed up and stowed away in these carts, which were sent forward, three days in advance, to Kalgan, a frontier town of Mongolia. And all these preparations being completed, and every precaution taken, the 17th of May was appointed as the day of departure.

Thenceforth, and throughout the journey, Madame de Bourboulon adopted a masculine costume—that is, a vest of grey cloth, with velvet trimmings, loose pantaloons of blue stuff, spurred boots, and at need a Mongolian cloak with a double hood of furs. She mounted her favourite horse, which she had taken with her to Pekin, and it had been her companion in all her excursions in the city and the surrounding country.

At six o'clock in the morning everybody was assembled in the court of the yamoun of the French legation. Sir Frederick Bruce, the English minister; Mr. Wade, the secretary to the English legation; M. Trèves, a French naval lieutenant, and some young French interpreters were present.

Two Chinese mandarins—one with the red button; the other, his inferior in rank, with the white—gravely awaited the moment of departure to escort the travellers as far as Kalgan, and to take care that, upon requisition being made, they were provided with everything necessary to their comfort. Numerous Tching-taï, the

[Pg 279]

official messengers of the legations, and other indigenous domestics, crowded the court, gravely mounted upon foundered broken-down hacks, their knees raised up to their elbows, and their hands clutching at the mane of their Rosinante, like apes astride of dogs in the arena of the circus. A couple of litters, carried by mules, were also prepared; one was intended for Madame de Bourboulon, in case of need, the other for the conveyance of five charming little Chinese dogs which she hoped to transport to Europe. At length the mandarin of the red button came to take the ambassador's orders, and gave the signal of departure.

At this moment the air resounded with noisy detonations: fusees, serpents, and petards exploded in all directions

—at the gate, in the gardens, even upon the walls of the legation. Great confusion followed, as no one was prepared for this point-blank politeness, so mysteriously organized by the Chinese servants. In China nothing takes place without a display of fireworks. About an hour was spent in reorganizing the caravan. Meanwhile, Madame de Bourboulon, whose frightened horse had carried her through the town, waited in a great open space some distance off. It was the first time, she says, that she had been alone in the midst of that great town. She had succeeded in pulling up her horse near a pagoda, which she did not know, because she had never visited that quarter of Pekin; her masculine garb attracted curiosity, and she was speedily surrounded by an immense crowd.

Though its

[Pg 280]

demeanour towards her was peaceable and respectful, she found the time very long, and it was with intense satisfaction she rejoined the cavalcade, the members of which had begun to feel alarmed at her absence.

The whole company being once more reunited, they passed the walled enclosure of the great city, garrisoned by a body of the so-called "Imperial Tigers," and entered the northern suburb.

The great road of Mongolia is lined on both sides with pagodas, houses, and a host of small wayside public inns, painted with stripes of red, green, and blue, and surmounted by the most attractive signs. There is a constant succession of caravans of camels, directed by Mongols, Turcomans, Tibetans; of troops of mules, with clinking bells, bringing salt from Setchouan or tea from Hou-pai; and of immense herds of horned cattle, horses, and sheep, in charge of the dexterous horsemen of the Tchakar, who keep them together by the utterance of loud guttural cries, and by dealing them smart cuts with their long whips.

About one hour after noon, the caravan arrived at Sha-ho, a village situated between the two arms of a river of the same name (which means "the river of sand"). Madame de Bourboulon thus describes the hospitable reception given to the travellers:—

"We knocked at the door of a tolerably spacious house, situated near the entrance to the village: it was an elementary school; we could hear the nasal drone of the

[Pg 281]

children repeating their lessons. The schoolmaster, a crabbed Chinaman, scared by my presence, placed himself on the threshold, and looked as if he would not allow me to enter. But at the explanations made in good Chinese by Mr. Wade, the surly old fellow, undergoing a sudden metamorphosis, bent his lean spine in two, and ushered me, with many forced obeisances, into his wives' room. There, before I had time to recollect myself, these ladies carried me off by force of arms, and installed me upon a kang or couch, where I had scarcely stretched my limbs before I was offered the inevitable tea. I was gradually passing into a delightful dizziness, when a disquieting thought suddenly restored all my energy: I was lying on a heap of rags and tatters of all colours, and certainly the kang possessed other inhabitants than myself. I immediately arose, in spite of the protestations of my Chinese hostesses, and took a seat in the courtyard under the galleries. When I was a little rested, I seated myself in my litter, and about half-past six in the evening we arrived at the town of Tchaing-ping-tchan."

On the following day our travellers turned aside to visit the famous sepulchre of the Mings—a vast collection of monuments, which the Chinese regard as one of the finest specimens of the art of the seventeenth century—that is, the seventeenth century of their chronology. And, first, there are gigantic monoliths crowned with twelve stones placed perpendicularly, and surmounted by five roofs in varnished and gilded tiles; next, a monumental triumphal arch

[Pg 282]

in white marble, with three immense gateways; through the central one may be seen a double row of gigantic monsters in enamelled stone, painted in dazzling colours; finally, you pass into an enclosure with a gigantic tortoise in front of it, bearing on its back a marble obelisk covered with inscriptions. At the time of Madame de Bourboulon's visit the entrance was closed, and while the Ting-tchaï went in search of the guardians, she and her companions dismounted, seated themselves on the greensward, in the shadow of some colossal larches, and enjoyed a pleasant repast, the sepulchral stones serving as tables.

"'Oh,' she exclaims, 'ye old emperors of the ancient dynasties, if any of your seers could but have told you that one day the barbarians of the remote West, whose despised name had scarcely reached your ears, would come to disturb the peace of your manes with the clinking of their glasses and the report of their champagne corks!'... But at length the keys are turned in the rusty locks, the guardian of the first enclosure offers us tea, and we distribute some money among the attendants.... In China, perhaps more even than in Europe, this is an inevitable formula: the famous principle of nothing for nothing must have been invented in the Celestial Empire. Out of respect, or for some other reason, the guardians left us free to go and come at will, dispensing with the labour of following us. At first we traversed a spacious square court, paved with white marble, planted with yews and cypresses, cut into shapes as at Versailles, and

[Pg 283]

peopled with an infinite number of statues; then we climbed a superb marble staircase of thirty steps, which led to another square court, planted in the same style, and shut in on the right and left by a thick forest of huge cedars, which conceals eight temples with circular cupolas, crowned and ornamented by the grimacing gods of the Chinese Trinity, with their six arms and six heads. Now another staircase, leading to a circular platform in white marble, in the middle of which rises the grand mausoleum. It is of marble; a great bronze door admits to the interior. We pass under a vault, the niches of which enclose the bones of the Ming emperors; a spiral staircase, with sculptured balustrades, very handsome in style, conducts to a second platform, elevated some seventy feet above the ground. The view from it is magnificent, overlooking a world of mausoleums, pagodas, temples, and kiosks, which the great trees had concealed from us.

"The mausoleum is continued into an immense cupola, and terminates in a pointed pyramid, covered with plates and mythological bas-reliefs. Finally, the pyramid is crowned by a great gilded ball."

The travellers here quitted their English horses, and mounted the frightful Chinese steeds which carry on the postal service. After a couple of wearisome days, occupied in clearing narrow defiles, torrents, and plains of blinding dust, they reached the Lazarist Mission.

On entering the town, they were surrounded by an immense multitude, all silent and polite, but not the less

[Pg 284]

fatiguing— gênant, as Madame de Bourboulon puts it. "Their eager curiosity did not fail to become very inconvenient, and we could well have dispensed with the 20,000 quidnuncs who accompanied us everywhere. We halted at last before the great gateway above which figures, though only for a few days, the cross, that noble symbol of the Latin civilization. It is the standard of humanity, of generous ideas and universal emancipation, placed throughout the extreme East under the protection of France. The English occupy themselves wholly with commerce: for them, faith and the sublime teachings of religion take but the second place."

Very few French travellers seem able to avoid an occasional outbreak of splenetic patriotism. The greatness and the generosity of France are the hobby-horse on which they ride with such a fanfare of trumpets as to provoke the ridicule of the passer-by. Madame de Bourboulon, as a woman, may be excused her little bit of sarcasm, though she must have known and ought to have remembered what has been done and endured by English missionaries in the name and for the sake of the cross of Christ.

The Lazarist priests gave our travellers a hearty welcome; and after a good night's rest, the caravan quitted Suan-hou-pu, a large town, remarkable for the number of Chinese Mussulmans who inhabit it. They reached Kalgan on the 23rd of May, and were greeted by Madame de Baluseck, who was to return to Europe in company with Madame de Bourboulon. Thus, as Sir

[Pg 285]

Frederick Bruce was still with them, the representatives of the three greatest Powers in the world met together in this remote town, which, previously, was almost unknown to Europeans.

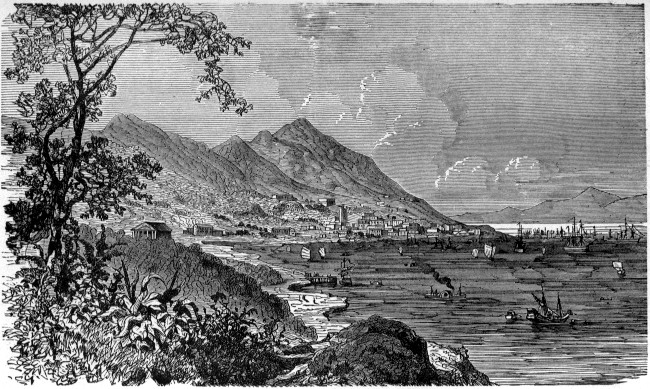

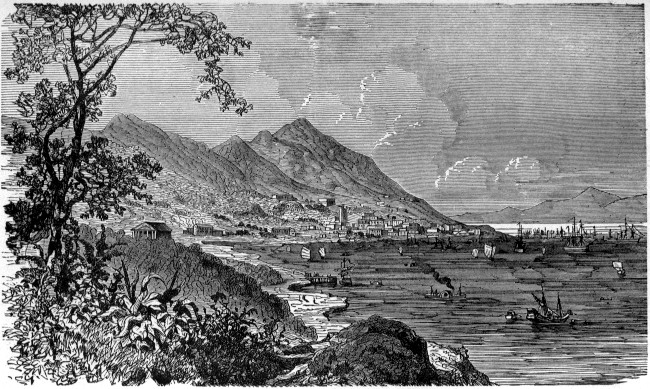

Kalgan, the frontier town of Mongolia, is not so well built as the imperial cities; it is a commercial centre, where bazaars abound, and open stalls; the foot passengers touch the walls of the houses as they file by, one after the other, and the roadway, narrow, squalid, and muddy, is thronged with chariots, camels, mules, and horses. "I have been much struck," writes Madame de Bourboulon, "with the extreme variety of costumes and types resulting from the presence of numerous foreign merchants. Here, as in all Chinese towns, the traders at every door tout for custom. Here, porters trudge by loaded with bales of tea; there, under an awning of felt, are encamped itinerant restaurateurs with their cooking-stoves; yonder, the mendicant bonzes beat the tam-tam, and second-hand dealers display their wares.

"Ragged Tartars, with their legs bare, drive onward herds of cattle, without thought of passers-by; while Tibetans display their sumptuous garb, their blue caps with red top-knots, and their loose-lowing hair. Farther off, the camel-drivers of Turkistan, turbaned, with aquiline nose and long black beard, lead along, with strange airs, their camels loaded with salt; finally, the Mongolian Lamas, in red and yellow garments, and shaven crowns, gallop past on their untrained steeds, in striking contrast

[Pg 286]

to the calm bearing of a Siberian merchant, who stalks along in his thick fur-lined pelisse, great boots, and large felt hat.

"Behold me now in the street of the clothes-merchants; there are more second-hand dealers than tailors in China; one has no repugnance for another's cast-off raiment, and frequently one does not deign even to clean it. I enter a fashionable shop: the master is a natty little old man, his nose armed with formidable spectacles which do but partly conceal his dull, malignant eyes. Three young people in turn exhibit to the passer-by his different wares, extolling their quality, and making known their prices. This is the custom; and to me it seems more ingenious and better adapted to attract purchasers, than the artistically arranged shop-windows which one sees in Europe. I allowed myself to be tempted, and purchased a blue silk pelisse, lined with white wool; this wool, as soft and fine as silk, comes from the celebrated race of the Ong-ti sheep. I paid for it double its value, but the master of the establishment was so persuasive, so irresistible, that I could not refuse, and I then left immediately, for he was quite capable of making me buy up the whole of his shop. The Chinese are certainly the cleverest traders in the world, and I predict that they will prove formidable competitors to the dealers of London and Paris, if it should ever occur to them to set up their establishments in Europe.

"After dinner, M. de Baluseck took leave of his wife, and set out on his return to Pekin; Sir F. Bruce goes

[Pg 287]

with us as far as Bourgaltaï, the first station in Mongolia. From our halting-place I can perceive the ramifications of the Great Wall, stretching northward of the town towards the crest of the mountains. Kaigan, which has a population of 200,000 souls, is the northernmost town of China proper."

On the 24th of May, the travellers, accompanied by Madame de Baluseck, departed from Kaigan and crossed the Great Wall. This colossal defensive work consists of double crenelated ramparts, locked together, at intervals of about 100 yards, by towers and other fortifications. The ramparts are built of brickwork and ash-tar cemented with lime; measure twenty feet in height, and twenty-five to thirty feet in thickness; but do not at all points preserve this solidity. In the province of Kansou, there is but one line of rampart. The total length of this great barrier, called Wan-ti-chang (or "myriad-mile wall") by the Chinese, is 1,250 miles. It was built about 220 b.c., as a protection against the Tartar marauders, and extends from 3° 30' E. to 15° W. of Pekin, surmounting the highest hills, descending into the deepest valleys, and bridging the most formidable rivers.

Our travelers entered Bourgaltaï in the evening, simultaneously with the caravan of camels, which had started a fortnight before, and were lodged in a squalid and filthy inn. Nothing, however, could disturb the cheerful temperament of Madame de Bourboulon, who rose superior to every inconvenience or vexation, and this

bonhommie is the chief charm of her book. Thus,

[Pg 288]

speaking of the first evening in this dirty Mongolian inn, she says:—"There was nothing to be done but to be content with some cold provisions, and our camping-out beds. It was the birthday of Queen Victoria, and as our landlord was able to put his hand upon two bottles of champagne, we drank, along with Sir Frederick Bruce and Mr. Wade, her Majesty's health. Afterwards we played a rubber at whist (for we had found some cards). Surely, never before was whist played in the Mongolian deserts!"

Before accompanying our travellers into these deserts, it may be convenient that we should note the personnel of their following, and the organization of their expedition. In addition to Monsieur and Madame de Bourboulon, the French caravan consisted of six persons:—Captain Bouvier, of the Engineers; a sergeant and a private of the same branch of the service; an artillerist; a steward ( intendant); and a young Christian, a native of Pekin, whom M. de Bourboulon was taking with him to France. Madame de Baluseck's suite consisted of a Russian physician; a French waiting maid; a Lama interpreter, named Gomboï; and a Cossack (as escort). A small carriage, well hung on two wheels, was provided for the two ladies. The other travellers journeyed on horseback or in Chinese carts.

These small carts, with hoods of blue cloth, carry only one passenger; they are not hung upon springs, but are solidly constructed.