Chapter IX.

Twenty Hill Hollow[12]

Were we to cross-cut the Sierra Nevada into blocks a dozen miles or so in thickness, each section would contain a Yosemite Valley and a river, together with a bright array of lakes and meadows, rocks and forests. The grandeur and inexhaustible beauty of each block would be so vast and over-satisfying that to choose among them would be like selecting slices of bread cut from the same loaf. One bread-slice might have burnt spots, answering to craters; another would be more browned; another, more crusted or raggedly cut; but all essentially the same. In no greater degree would the Sierra slices differ in general character. Nevertheless, we all would choose the Merced slice, because, being easier of access, it has been nibbled and tasted, and pronounced very good; and because of the concentrated form of its Yosemite, caused by certain conditions of baking, yeasting, and glacier-frosting of this portion of the great Sierra loaf. In like manner, we readily perceive that the great central plain is one batch of bread—one golden cake—and we are loath to leave these magnificent loaves for crumbs, however good.

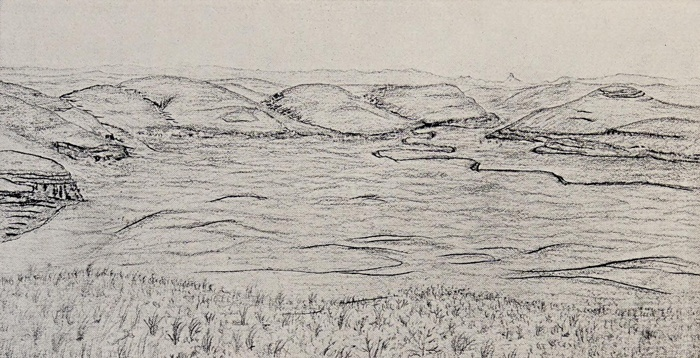

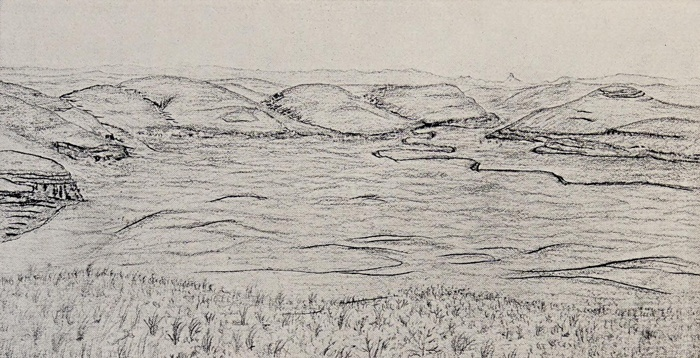

After our smoky sky has been washed in the rains of winter, the whole complex row of Sierras appears from the plain as a simple wall, slightly beveled, and colored in horizontal bands laid one above another, as if entirely composed of partially straightened rainbows. So, also, the plain seen from the mountains has the same simplicity of smooth surface, colored purple and yellow, like a patchwork of irised clouds. But when we descend to this smooth-furred sheet, we discover complexity in its physical conditions equal to that of the mountains, though less strongly marked. In particular, that portion of the plain lying between the Merced and the Tuolumne, within ten miles of the slaty foothills, is most elaborately carved into valleys, hollows, and smooth undulations, and among them is laid the Merced Yosemite of the plain—Twenty Hill Hollow.

Twenty Hill Hollow

From a sketch by Mr. Muir

This delightful Hollow is less than a mile in length, and of just sufficient width to form a well-proportioned oval. It is situated about midway between the two rivers, and five miles from the Sierra foothills. Its banks are formed of twenty hemispherical hills; hence its name. They surround and enclose it on all sides, leaving only one narrow opening toward the southwest for the escape of its waters. The bottom of the Hollow is about two hundred feet below the level of the surrounding plain, and the tops of its hills are slightly below the general level. Here is no towering dome, no Tissiack, to mark its place; and one may ramble close upon its rim before he is made aware of its existence. Its twenty hills are as wonder-fully regular in size and position as in form. They are like big marbles half buried in the ground, each poised and settled daintily into its place at a regular distance from its fellows, making a charming fairy-land of hills, with small, grassy valleys between, each valley having a tiny stream of its own, which leaps and sparkles out into the open hollow, uniting to form Hollow Creek.

Like all others in the immediate neighborhood, these twenty hills are composed of stratified lavas mixed with mountain drift in varying proportions. Some strata are almost wholly made up of volcanic matter lava and cinders—thoroughly ground and mixed by the waters that deposited them; others are largely composed of slate and quartz boulders of all degrees of coarseness, forming conglomerates. A few clear, open sections occur, exposing an elaborate history of seas, and glaciers, and volcanic floods—chapters of cinders and ashes that picture dark days when these bright snowy mountains were clouded in smoke and rivered and laked with living fire. A fearful age, say mortals, when these Sierras flowed lava to the sea. What horizons of flame! What atmospheres of ashes and smoke!

The conglomerates and lavas of this region are readily denuded by water. In the time when their parent sea was removed to form this golden plain, their regular surface, in great part covered with shallow lakes, showed little variation from motionless level until torrents of rain and floods from the mountains gradually sculptured the simple page to the present diversity of bank and brae, creating, in the section between the Merced and the Tuolumne, Twenty Hill Hollow, Lily Hollow, and the lovely valleys of Cascade and Castle Creeks, with many others nameless and unknown, seen only by hunters and shepherds, sunk in the wide bosom of the plain, like undiscovered gold. Twenty Hill Hollow is a fine illustration of a valley created by erosion of water. Here are no Washington columns, no angular El Capitans. The hollow cañons, cut in soft lavas, are not so deep as to require a single earthquake at the hands of science, much less a baker’s dozen of those convenient tools demanded for the making of mountain Yosemites, and our moderate arithmetical standards are not outraged by a single magnitude of this simple, comprehensible hollow.

The present rate of denudation of this portion of the plain seems to be about one tenth of an inch per year. This approximation is based upon observations made upon stream-banks and perennial plants. Rains and winds remove mountains without disturbing their plant or animal inhabitants. Hovering petrels, the fishes and floating plants of ocean, sink and rise in beautiful rhythm with its waves; and, in like manner, the birds and plants of the plain sink and rise with these waves of land, the only difference being that the fluctuations are more rapid in the one case than in the other.

In March and April the bottom of the Hollow and every one of its hills are smoothly covered and plushed with yellow and purple flowers, the yellow predominating. They are mostly social Compositæ, with a few claytonias, gilias, eschscholtzias, white and yellow violets, blue and yellow lilies, dodecatheons, and eriogonums set in a half-floating maze of purple grasses. There is but one vine in the Hollow—the Megarrhiza [Echinocystis T. & D.] or “Big Root.” The only bush within a mile of it, about four feet in height, forms so remark-able an object upon the universal smoothness that my dog barks furiously around it, at a cautious distance, as if it were a bear. Some of the hills have rock ribs that are brightly colored with red and yellow lichens, and in moist nooks there are luxuriant mosses—Bartramia, Dicranum, Funaria, and several Hypnums. In cool, sunless coves the mosses are companioned with ferns—a Cystopteris and the little gold-dusted rock fern, Gymnogramma triangularis.

The Hollow is not rich in birds. The meadow-lark homes there, and the little burrowing owl, the killdeer, and a species of sparrow. Occasionally a few ducks pay a visit to its waters, and a few tall herons—the blue and the white—may at times be seen stalking along the creek; and the sparrow hawk and gray eagle[13] come to hunt. The lark, who does nearly all the singing for the Hollow, is not identical in species with the meadowlark of the East, though closely resembling it; richer flowers and skies have inspired him with a better song than was ever known to the Atlantic lark.

I have noted three distinct lark-songs here. The words of the first, which I committed to memory at one of their special meetings, spelled as sung, are, “Wee-ro spee-ro wee-o weer-ly wee-it.” On the 20th of January, 1869, they sang “Queed-lix boodle,” repeating it with great regularity, for hours together, to music sweet as the sky that gave it. On the 22d of the same month, they sang “Chee chool cheedildy choodildy.” An inspiration is this song of the blessed lark, and universally absorbable by human souls. It seems to be the only bird-song of these hills that has been created with any direct reference to us. Music is one of the attributes of matter, into whatever forms it may be organized. Drops and sprays of air are specialized, and made to plash and churn in the bosom of a lark, as infinitesimal portions of air plash and sing about the angles and hollows of sand-grains, as perfectly composed and predestined as the rejoicing anthems of worlds; but our senses are not fine enough to catch the tones. Fancy the waving, pulsing melody of the vast flower-congregations of the Hollow flowing from myriad voices of tuned petal and pistil, and heaps of sculptured pollen. Scarce one note is for us; nevertheless, God be thanked for this blessed instrument hid beneath the feathers of a lark.

The eagle does not dwell in the Hollow; he only floats there to hunt the long-eared hare. One day I saw a fine specimen alight upon a hillside. I was at first puzzled to know what power could fetch the sky-king down into the grass with the larks. Watching him attentively, I soon discovered the cause of his earthiness. He was hungry and stood watching a long-eared hare, which stood erect at the door of his burrow, staring his winged fellow mortal full in the face. They were about ten feet apart. Should the eagle attempt to snatch the hare, he would instantly disappear in the ground. Should long-ears, tired of inaction, venture to skim the hill to some neighboring burrow, the eagle would swoop above him and strike him dead with a blow of his pinions, bear him to some favorite rock table, satisfy his hunger, wipe off all marks of grossness, and go again to the sky.

Since antelopes have been driven away, the hare is the swiftest animal of the Hollow. When chased by a dog he will not seek a burrow, as when the eagle wings in sight, but skims wavily from hill to hill across connecting curves, swift and effortless as a bird-shadow. One that I measured was twelve inches in height at the shoulders. His body was eighteen inches, from nose-tip to tail. His great ears measured six and a half inches in length and two in width. His ears which, notwithstanding their great size, he wears gracefully and becomingly—have procured for him the homely nickname, by which he is commonly known, of “Jackass rabbit.” Hares are very abundant over all the plain and up in the sunny, lightly wooded foothills, but their range does not extend into the close pine forests.

Coyotes, or California wolves, are occasionally seen gliding about the Hollow, but they are not numerous, vast numbers having been slain by the traps and poisons of sheep-raisers. The coyote is about the size of a small shepherd-dog, beautiful and graceful in motion, with erect ears, and a bushy tail, like a fox. Inasmuch as he is fond of mutton, he is cordially detested by “sheep-men” and nearly all cultured people.

The ground-squirrel is the most common animal of the Hollow. In several hills there is a soft stratum in which they have tunneled their homes. It is interesting to observe these rodent towns in time of alarm. Their one circular street resounds with sharp, lancing outcries of “Seekit, seek, seek, seekit!” Near neighbors, peeping cautiously half out of doors, engage in low, purring chat. Others, bolt upright on the doorsill or on the rock above, shout excitedly as if calling attention to the motions and aspects of the enemy. Like the wolf, this little animal is accursed, because of his relish for grain. What a pity that Nature should have made so many small mouths palated like our own!

All the seasons of the Hollow are warm and bright, and flowers bloom through the whole year. But the grand commencement of the annual genesis of plant and insect life is governed by the setting-in of the rains, in December or January. The air, hot and opaque, is then washed and cooled. Plant seeds, which for six months have lain on the ground dry as if garnered in a farmer’s bin, at once unfold their treasured life. Flies hum their delicate tunes. Butterflies come from their coffins, like cotyledons from their husks. The network of dry water-courses, spread over valleys and hollows, suddenly gushes with bright waters, sparkling and pouring from pool to pool, like dusty mummies risen from the dead and set living and laughing with color and blood. The weather grows in beauty, like a flower. Its roots in the ground develop day-clusters a week or two in size, divided by and shaded in foliage of clouds; or round hours of ripe sunshine wave and spray in sky-shadows, like racemes of berries half hidden in leaves.

These months of so-called rainy season are not filled with rain. Nowhere else in North America, perhaps in the world, are Januarys so balmed and glowed with vital sunlight. Referring to my notes of 1868 and 1869, I find that the first heavy general rain of the season fell on the 18th of December. January yielded to the Hollow, during the day, only twenty hours of rain, which was divided among six rainy days. February had only three days on which rain fell, amounting to eighteen and one-half hours in all. March had five rainy days. April had three, yielding seven hours of rain. May also had three wet days, yielding nine hours of rain, and completed the so-called “rainy season” for that year, which is probably about an average one. It must be remembered that this rain record has nothing to do with what fell in the night.

The ordinary rainstorm of this region has little of that outward pomp and sublimity of structure so characteristic of the storms of the Mississippi Valley. Nevertheless, we have experienced rainstorms out on these treeless plains, in nights of solid darkness, as impressively sublime as the noblest storms of the mountains. The wind, which in settled weather blows from the northwest, veers to the southeast; the sky curdles gradually and evenly to a grainless, seamless, homogeneous cloud; and then comes the rain, pouring steadily and often driven aslant by strong winds. In 1869, more than three fourths of the winter rains came from the southeast. One magnificent storm from the northwest occurred on the 21st of March; an immense, round-browed cloud came sailing over the flowery hills in most imposing majesty, bestowing water as from a sea. The passionate rain-gush lasted only about one minute, but was nevertheless the most magnificent cataract of the sky mountains that I ever beheld. A portion of calm sky toward the Sierras was brushed with thin, white cloud-tissue, upon which the rain-torrent showed to a great height a cloud waterfall, which, like those of Yosemite, was neither spray, rain, nor solid water. In the same year the cloudiness of January, omitting rainy days, averaged 0.32; February, 0.13; March, 0.20; April, 0.10; May, 0.08. The greater portion of this cloudiness was gathered into a few days, leaving the others blocks of solid, universal sunshine in every chink and pore.

At the end of January, four plants were in flower: a small white cress, growing in large patches; a low-set, umbeled plant, with yellow flowers; an eriogonum, with flowers in leafless spangles; and a small boragewort. Five or six mosses had adjusted their hoods, and were in the prime of life. In February, squirrels, hares, and flowers were in springtime joy. Bright plant-constellations shone everywhere about the Hollow. Ants were getting ready for work, rubbing and sunning their limbs upon the husk-piles around their doors; fat, pollen-dusted, “burly, dozing humble-bees” were rumbling among the flowers; and spiders were busy mending up old webs, or weaving new ones. Flowers were born every day, and came gushing from the ground like gayly dressed children from a church. The bright air became daily more songful with fly-wings, and sweeter with breath of plants.

In March, plant-life is more than doubled. The little pioneer cress, by this time, goes to seed, wearing daintily embroidered silicles. Several claytonias appear; also, a large white leptosiphon[?], and two nemophilas. A small plantago becomes tall enough to wave and show silky ripples of shade. Toward the end of this month or the beginning of April, plant-life is at its greatest height. Few have any just conception of its amazing richness. Count the flowers of any portion of these twenty hills, or of the bottom of the Hollow, among the streams: you will find that there are from one to ten thousand upon every square yard, counting the heads of Compositæ as single flowers. Yellow Compositæ form by far the greater portion of this goldy-way. Well may the sun feed them with his richest light, for these shining sunlets are his very children—rays of his ray, beams of his beam! One would fancy that these California days receive more gold from the ground than they give to it. The earth has indeed become a sky; and the two cloudless skies, raying toward each other flower-beams and sun-beams, are fused and congolded into one glowing heaven. By the end of April most of the Hollow plants have ripened their seeds and died; but, undecayed, still assist the landscape with color from persistent involucres and corolla-like heads of chaffy scales.

In May, only a few deep-set lilies and eriogonums are left alive. June, July, August, and September are the season of plant rest, followed, in October, by a most extraordinary out-gush of plant-life, at the very driest time of the whole year. A small, unobtrusive plant, Hemizonia virgata, from six inches to three feet in height, with pale, glandular leaves, suddenly bursts into bloom, in patches miles in extent, like a resurrection of the gold of April. I have counted upward of three thousand heads upon one plant. Both leaves and pedicles are so small as to be nearly invisible among so vast a number of daisy golden-heads that seem to keep their places unsupported, like stars in the sky. The heads are about five eighths of an inch in diameter; rays and disk-flowers, yellow; stamens, purple. The rays have a rich, furred appearance, like the petals of garden pansies. The prevailing summer wind makes all the heads turn to the southeast. The waxy secretion of its leaves and involucres has suggested its grim name of “tarweed,” by which it is generally known. In our estimation, it is the most delightful member of the whole Composite Family of the plain. It remains in flower until November, uniting with an eriogonum that continues the floral chain across December to the spring plants of January. Thus, although nearly all of the year’s plant-life is crowded into February, March, and April, the flower circle around the Twenty Hill Hollow is never broken.

The Hollow may easily be visited by tourists en route for Yosemite, as it is distant only about six miles from Snelling’s. It is at all seasons interesting to the naturalist; but it has little that would interest the majority of tourists earlier than January or later than April. If you wish to see how much of light, life, and joy can be got into a January, go to this blessed Hollow. If you wish to see a plant-resurrection,—myriads of bright flowers crowding from the ground, like souls to a judgment,—go to Twenty Hills in February. If you are traveling for health, play truant to doctors and friends, fill your pocket with biscuits, and hide in the hills of the Hollow, lave in its waters, tan in its golds, bask in its flower-shine, and your baptisms will make you a new creature indeed. Or, choked in the sediments of society, so tired of the world, here will your hard doubts disappear, your carnal incrustations melt off, and your soul breathe deep and free in God’s shoreless atmosphere of beauty and love.

Never shall I forget my baptism in this font. It happened in January, a resurrection day for many a plant and for me. I suddenly found myself on one of its hills; the Hollow overflowed with light, as a fountain, and only small, sunless nooks were kept for mosseries and ferneries. Hollow Creek spangled and mazed like a river. The ground steamed with fragrance. Light, of unspeakable richness, was brooding the flowers. Truly, said I, is California the Golden State—in metallic gold, in sun gold, and in plant gold. The sunshine for a whole summer seemed condensed into the chambers of that one glowing day. Every trace of dimness had been washed from the sky; the mountains were dusted and wiped clean with clouds—Pacheco Peak and Mount Diablo, and the waved blue wall between; the grand Sierra stood along the plain, colored in four horizontal bands:—the lowest, rose purple; the next higher, dark purple; the next, blue; and, above all, the white row of summits pointing to the heavens.

It may be asked, What have mountains fifty or a hundred miles away to do with Twenty Hill Hollow? To lovers of the wild, these mountains are not a hundred miles away. Their spiritual power and the goodness of the sky make them near, as a circle of friends. They rise as a portion of the hilled walls of the Hollow. You cannot feel yourself out of doors; plain, sky, and mountains ray beauty which you feel. You bathe in these spirit-beams, turning round and round, as if warming at a camp-fire. Presently you lose consciousness of your own separate existence: you blend with the landscape, and become part and parcel of nature.

The End