Carpentry

I stood tall as any man, just like old oak tree

I wasn’t being anyone else

I was only being me

Time has done as old men told it would be

To be yourself is very costly

But great the reward of being free

~ Gemini Joe ~

ne day the principal and a teacher came to my home. They spoke to my parents. “Joey's a good artist, you know. He has something here that we are all admiring. We think you should send him to art school. They told my father it would cost eight dollars.

My dad said, “Oh boy, that’s a lot of money. If things get better we’ll let you know.”

That never happened, but I wasn’t down about it. At that time, you couldn’t do things like that. I just packed my art supplies in a box and put them under my bed.

My friend Jim graduated to the seventh grade, but I wasn’t so lucky. Left back, I didn’t have my friend around to help pass the time. Embarrassed to be the oldest kid in my class, I stopped going.

I said, “Pop! You can send me to do your rounds.”

My father didn’t like that.

“This is a dirty business. The only reason I do it is to make sure my children have a chance at a better life. I want you to be a law-abiding citizen and learn a legitimate trade.”

“What kind of trade?”

“What about carpentry? Carpentry is a good profession and you’ll never go hungry if you learn how to build things. I know a man who owns a wood shop close by. He owes me a favor and he’s agreed to take you on as an apprentice.”

I really didn’t want to be a carpenter. I wanted to work on cars, but my father thought it was a good idea so I agreed. He took me to see his friend.

The old man was measuring a piece of lumber and I was very interested. My dad and me watched as he carefully marked a line with white chalk and then turned on his saw. Sawdust flew everywhere and some went in my eyes. When it cleared, I was amazed. It was cut in a perfect line.

When my father left, the man took me into a big garage, where there was a load of lumber was stacked all the way up to the ceiling and gave me a crowbar and a hammer.

“Okay, take all the nails out, straighten them out, and put them in a cigar box according to their size.”

I gaped at the wood and looked at the heavy hammer in my hands.

“But my father said….”

The old man grabbed the hammer and demonstrated. “See? Like this.” He shoved the hammer back into my hand.

When my father came to get me, I pleaded, “Please, Pop, don’t make me come back here.”

“Let’s give it a few more days,” he said. “Maybe tomorrow will be different.”

The next day, I walked to the carpenter’s shop with my father.

Soon after Dad left, the man gave me the hammer and pointed to the wood.

“You know what to do.”

I only did that for two days until I couldn’t take it anymore.

Dad confronted the old carpenter. “You told me you needed an apprentice. All you did was to teach him to pull nails.”

“I thought it best if he learned how to use a hammer, first,” he said.

A few weeks later on the way to the train station, I passed the shop. A large sign hung on the door that read, CLOSED. I felt bad for the old man and hoped it wasn’t my fault.

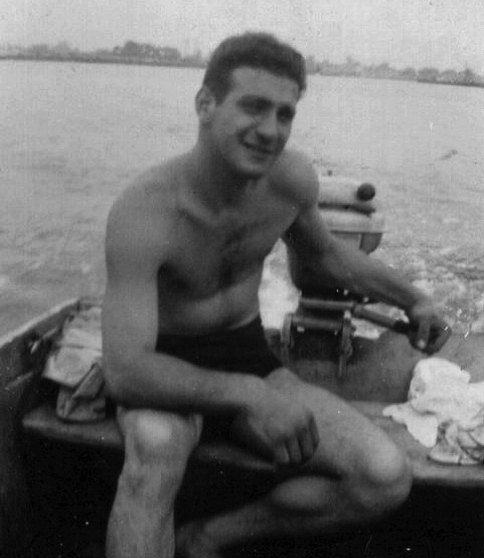

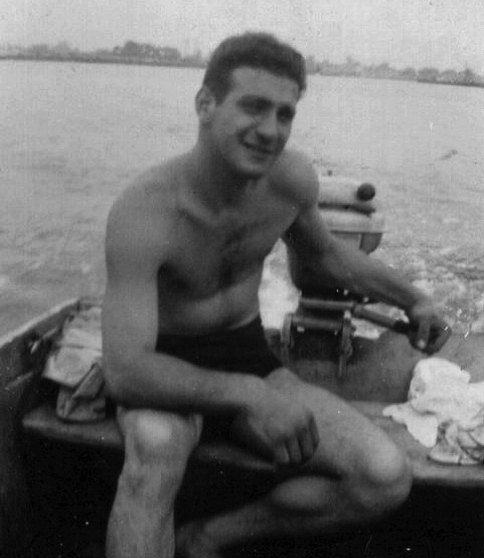

Since I had learned a little about carpentry, I decided that I wanted to build my own rowboat. My brother Victor wanted to help.

“We’ll build it outside in the yard,” I said.

“No, the winter is coming in,” he pointed out. “Let’s build it in the basement. We’ll have plenty of time and heat and light.”

I thought that was a very good idea. I told him to measure the doors so we could get the boat out. When the boat was finished, well it wouldn’t go out.

“You measured it wrong,” I told Victor.

My brother was blowing his top. He ran out of the house screaming, yelling, and cursing. When he was gone, I sat there wondering what to do. Then I remembered… the seat in the center of the boat made an arch. If I removed the seat, I would gain an inch or two and the boat would fit through the door.

When my brother got back, that boat was halfway out. He said, “Damn it Joe. How did you do that?”