CHAPTER XI

SIDELIGHTS ON SHERLOCK HOLMES

“The Speckled Band”—Barrie’s Parody on Holmes—Holmes on the Films—Methods of Construction—Problems—Curious Letters—Some Personal Cases—Strange Happenings.

I may as well interrupt my narrative here in order to say what may interest my readers about my most notorious character.

The impression that Holmes was a real person of flesh and blood may have been intensified by his frequent appearance upon the stage. After the withdrawal of my dramatization of “Rodney Stone” from a theatre upon which I held a six months’ lease, I determined to play a bold and energetic game, for an empty theatre spells ruin. When I saw the course that things were taking I shut myself up and devoted my whole mind to making a sensational Sherlock Holmes drama. I wrote it in a week and called it “The Speckled Band” after the short story of that name. I do not think that I exaggerate if I say that within a fortnight of the one play shutting down I had a company working upon the rehearsals of a second one, which had been written in the interval. It was a considerable success. Lyn Harding, as the half epileptic and wholly formidable Doctor Grimesby Rylott, was most masterful, while Saintsbury as Sherlock Holmes was also very good. Before the end of the run I had cleared off all that I had lost upon the other play, and I had created a permanent property of some value. It became a stock piece and is even now touring the country. We had a fine rock boa to play the title-rôle, a snake which was the pride of my heart, so one can imagine my disgust when I saw that one critic ended his disparaging review by the words “The crisis of the play was produced by the appearance of a palpably artificial serpent.” I was inclined to offer him a goodly sum if he would undertake to go to bed with it. We had several snakes at different times, but they were none of them born actors and they were all inclined either to hang down from the hole in the wall like inanimate bell-pulls, or else to turn back through the hole and get even with the stage carpenter who pinched their tails in order to make them more lively. Finally we used artificial snakes, and every one, including the stage carpenter, agreed that it was more satisfactory.

This was the second Sherlock Holmes play. I should have spoken about the first, which was produced very much earlier, in fact at the time of the African war. It was written and most wonderfully acted by William Gillette, the famous American. Since he used my characters and to some extent my plots, he naturally gave me a share in the undertaking, which proved to be very successful. “May I marry Holmes?” was one cable which I received from him when in the throes of composition. “You may marry or murder or do what you like with him,” was my heartless reply. I was charmed both with the play, the acting and the pecuniary result. I think that every man with a drop of artistic blood in his veins would agree that the latter consideration, though very welcome when it does arrive, is still the last of which he thinks.

Sir James Barrie paid his respects to Sherlock Holmes in a rollicking parody. It was really a gay gesture of resignation over the failure which we had encountered with a comic opera for which he undertook to write the libretto. I collaborated with him on this, but in spite of our joint efforts, the piece fell flat. Whereupon Barrie sent me a parody on Holmes, written on the fly leaves of one of his books. It ran thus:—

THE ADVENTURE OF THE TWO COLLABORATORS

In bringing to a close the adventures of my friend Sherlock Holmes I am perforce reminded that he never, save on the occasion which, as you will now hear, brought his singular career to an end, consented to act in any mystery which was concerned with persons who made a livelihood by their pen. “I am not particular about the people I mix among for business purposes,” he would say, “but at literary characters I draw the line.”

We were in our rooms in Baker Street one evening. I was (I remember) by the centre table writing out “The Adventure of the Man without a Cork Leg” (which had so puzzled the Royal Society and all the other scientific bodies of Europe), and Holmes was amusing himself with a little revolver practice. It was his custom of a summer evening to fire round my head, just shaving my face, until he had made a photograph of me on the opposite wall, and it is a slight proof of his skill that many of these portraits in pistol shots are considered admirable likenesses.

I happened to look out of the window, and perceiving two gentlemen advancing rapidly along Baker Street asked him who they were. He immediately lit his pipe, and, twisting himself on a chair into the figure 8, replied:

“They are two collaborators in comic opera, and their play has not been a triumph.”

I sprang from my chair to the ceiling in amazement, and he then explained:

“My dear Watson, they are obviously men who follow some low calling. That much even you should be able to read in their faces. Those little pieces of blue paper which they fling angrily from them are Durrant’s Press Notices. Of these they have obviously hundreds about their person (see how their pockets bulge). They would not dance on them if they were pleasant reading.”

I again sprang to the ceiling (which is much dented), and shouted: “Amazing! but they may be mere authors.”

“No,” said Holmes, “for mere authors only get one press notice a week. Only criminals, dramatists and actors get them by the hundred.”

“Then they may be actors.”

“No, actors would come in a carriage.”

“Can you tell me anything else about them?”

“A great deal. From the mud on the boots of the tall one I perceive that he comes from South Norwood. The other is as obviously a Scotch author.”

“How can you tell that?”

“He is carrying in his pocket a book called (I clearly see) ‘Auld Licht Something.’ Would any one but the author be likely to carry about a book with such a title?”

I had to confess that this was improbable.

It was now evident that the two men (if such they can be called) were seeking our lodgings. I have said (often) that my friend Holmes seldom gave way to emotion of any kind, but he now turned livid with passion. Presently this gave place to a strange look of triumph.

“Watson,” he said, “that big fellow has for years taken the credit for my most remarkable doings, but at last I have him—at last!”

Up I went to the ceiling, and when I returned the strangers were in the room.

“I perceive, gentlemen,” said Mr. Sherlock Holmes, “that you are at present afflicted by an extraordinary novelty.”

The handsomer of our visitors asked in amazement how he knew this, but the big one only scowled.

“You forget that you wear a ring on your fourth finger,” replied Mr. Holmes calmly.

I was about to jump to the ceiling when the big brute interposed.

“That Tommy-rot is all very well for the public, Holmes,” said he, “but you can drop it before me. And, Watson, if you go up to the ceiling again I shall make you stay there.”

Here I observed a curious phenomenon. My friend Sherlock Holmes shrank. He became small before my eyes. I looked longingly at the ceiling, but dared not.

“Let us cut the first four pages,” said the big man, “and proceed to business. I want to know why——”

“Allow me,” said Mr. Holmes, with some of his old courage. “You want to know why the public does not go to your opera.”

“Exactly,” said the other ironically, “as you perceive by my shirt stud.” He added more gravely, “And as you can only find out in one way I must insist on your witnessing an entire performance of the piece.”

It was an anxious moment for me. I shuddered, for I knew that if Holmes went I should have to go with him. But my friend had a heart of gold. “Never,” he cried fiercely, “I will do anything for you save that.”

“Your continued existence depends on it,” said the big man menacingly.

“I would rather melt into air,” replied Holmes, proudly taking another chair. “But I can tell you why the public don’t go to your piece without sitting the thing out myself.”

“Why?”

“Because,” replied Holmes calmly, “they prefer to stay away.”

A dead silence followed that extraordinary remark. For a moment the two intruders gazed with awe upon the man who had unravelled their mystery so wonderfully. Then drawing their knives——

Holmes grew less and less, until nothing was left save a ring of smoke which slowly circled to the ceiling.

The last words of great men are often noteworthy. These were the last words of Sherlock Holmes: “Fool, fool! I have kept you in luxury for years. By my help you have ridden extensively in cabs, where no author was ever seen before. Henceforth you will ride in buses!”

The brute sunk into a chair aghast.

The other author did not turn a hair.

To A. Conan Doyle,

from his friend

J. M. Barrie.

This parody, the best of all the numerous parodies, may be taken as an example not only of the author’s wit but of his debonnaire courage, for it was written immediately after our joint failure which at the moment was a bitter thought for both of us. There is indeed nothing more miserable than a theatrical failure, for you feel how many others who have backed you have been affected by it. It was, I am glad to say, my only experience of it, and I have no doubt that Barrie could say the same.

Before I leave the subject of the many impersonations of Holmes I may say that all of them, and all the drawings, are very unlike my own original idea of the man. I saw him as very tall—“over 6 feet, but so excessively lean that he seemed considerably taller,” said “A Study in Scarlet.” He had, as I imagined him, a thin razor-like face, with a great hawks-bill of a nose, and two small eyes, set close together on either side of it. Such was my conception. It chanced, however, that poor Sidney Paget who, before his premature death, drew all the original pictures, had a younger brother whose name, I think, was Walter, who served him as a model. The handsome Walter took the place of the more powerful but uglier Sherlock, and perhaps from the point of view of my lady readers it was as well. The stage has followed the type set up by the pictures.

Films of course were unknown when the stories appeared, and when these rights were finally discussed and a small sum offered for them by a French Company it seemed treasure trove and I was very glad to accept. Afterwards I had to buy them back again at exactly ten times what I had received, so the deal was a disastrous one. But now they have been done by the Stoll Company with Eille Norwood as Holmes, and it was worth all the expense to get so fine a production. Norwood has since played the part on the stage and won the approbation of the London public. He has that rare quality which can only be described as glamour, which compels you to watch an actor eagerly even when he is doing nothing. He has the brooding eye which excites expectation and he has also a quite unrivalled power of disguise. My only criticism of the films is that they introduce telephones, motor cars and other luxuries of which the Victorian Holmes never dreamed.

People have often asked me whether I knew the end of a Holmes story before I started it. Of course I do. One could not possibly steer a course if one did not know one’s destination. The first thing is to get your idea. Having got that key idea one’s next task is to conceal it and lay emphasis upon everything which can make for a different explanation. Holmes, however, can see all the fallacies of the alternatives, and arrives more or less dramatically at the true solution by steps which he can describe and justify. He shows his powers by what the South Americans now call “Sherlockholmitos,” which means clever little deductions which often have nothing to do with the matter in hand, but impress the reader with a general sense of power. The same effect is gained by his offhand allusion to other cases. Heaven knows how many titles I have thrown about in a casual way, and how many readers have begged me to satisfy their curiosity as to “Rigoletto and his abominable wife,” “The Adventure of the Tired Captain,” or “The Curious Experience of the Patterson Family in the Island of Uffa.” Once or twice, as in “The Adventure of the Second Stain,” which in my judgment is one of the neatest of the stories, I did actually use the title years before I wrote a story to correspond.

There are some questions concerned with particular stories which turn up periodically from every quarter of the globe. In “The Adventure of the Priory School” Holmes remarks in his offhand way that by looking at a bicycle track on a damp moor one can say which way it was heading. I had so many remonstrances upon this point, varying from pity to anger, that I took out my bicycle and tried. I had imagined that the observations of the way in which the track of the hind wheel overlaid the track of the front one when the machine was not running dead straight would show the direction. I found that my correspondents were right and I was wrong, for this would be the same whichever way the cycle was moving. On the other hand the real solution was much simpler, for on an undulating moor the wheels make a much deeper impression uphill and a more shallow one downhill, so Holmes was justified of his wisdom after all.

Sometimes I have got upon dangerous ground where I have taken risks through my own want of knowledge of the correct atmosphere. I have, for example, never been a racing man, and yet I ventured to write “Silver Blaze,” in which the mystery depends upon the laws of training and racing. The story is all right, and Holmes may have been at the top of his form, but my ignorance cries aloud to heaven. I read an excellent and very damaging criticism of the story in some sporting paper, written clearly by a man who did know, in which he explained the exact penalties which would have come upon every one concerned if they had acted as I described. Half would have been in jail and the other half warned off the turf for ever. However, I have never been nervous about details, and one must be masterful sometimes. When an alarmed Editor wrote to me once: “There is no second line of rails at that point,” I answered, “I make one.” On the other hand, there are cases where accuracy is essential.

I do not wish to be ungrateful to Holmes, who has been a good friend to me in many ways. If I have sometimes been inclined to weary of him it is because his character admits of no light or shade. He is a calculating machine, and anything you add to that simply weakens the effect. Thus the variety of the stories must depend upon the romance and compact handling of the plots. I would say a word for Watson also, who in the course of seven volumes never shows one gleam of humour or makes one single joke. To make a real character one must sacrifice everything to consistency and remember Goldsmith’s criticism of Johnson that “he would make the little fishes talk like whales.”

I do not think that I ever realized what a living actual personality Holmes had become to the more guileless readers, until I heard of the very pleasing story of the char-à-bancs of French schoolboys who, when asked what they wanted to see first in London, replied unanimously that they wanted to see Mr. Holmes’ lodgings in Baker Street. Many have asked me which house it is, but that is a point which for excellent reasons I will not decide.

There are certain Sherlock Holmes stories, apocryphal I need not say, which go round and round the press and turn up at fixed intervals with the regularity of a comet.

One is the story of the cabman who is supposed to have taken me to an hotel in Paris. “Dr. Doyle,” he cried, gazing at me fixedly, “I perceive from your appearance that you have been recently at Constantinople. I have reason to think also that you have been at Buda, and I perceive some indication that you were not far from Milan.” “Wonderful. Five francs for the secret of how you did it?” “I looked at the labels pasted on your trunk,” said the astute cabby.

Another perennial is of the woman who is said to have consulted Sherlock. “I am greatly puzzled, sir. In one week I have lost a motor horn, a brush, a box of golf balls, a dictionary and a bootjack. Can you explain it?” “Nothing simpler, madame,” said Sherlock. “It is clear that your neighbour keeps a goat.”

There was a third about how Sherlock entered heaven, and by virtue of his power of observation at once greeted Adam but the point is perhaps too anatomical for further discussion.

I suppose that every author receives a good many curious letters. Certainly I have done so. Quite a number of these have been from Russia. When they have been in the vernacular I have been compelled to take them as read, but when they have been in English they have been among the most curious in my collection.

There was one young lady who began all her epistles with the words “Good Lord.” Another had a large amount of guile underlying her simplicity. Writing from Warsaw, she stated that she had been bedridden for two years, and that my novels had been her only, etc., etc. So touched was I by this flattering statement that I at once prepared an autographed parcel of them to complete the fair invalid’s collection. By good luck, however, I met a brother author on the same day to whom I recounted the touching incident. With a cynical smile, he drew an identical letter from his pocket. His novels had also been for two years her only, etc., etc. I do not know how many more the lady had written to; but if, as I imagine, her correspondence had extended to several countries, she must have amassed a rather interesting library.

The young Russian’s habit of addressing me as “Good Lord” had an even stranger parallel at home which links it up with the subject of this article. Shortly after I received a knighthood, I had a bill from a tradesman which was quite correct and businesslike in every detail save that it was made out to Sir Sherlock Holmes. I hope that I can stand a joke as well as my neighbours, but this particular piece of humour seemed rather misapplied and I wrote sharply upon the subject.

In response to my letter there arrived at my hotel a very repentant clerk, who expressed his sorrow at the incident, but kept on repeating the phrase, “I assure you, sir, that it was bonâ fide.”

“What do you mean by bonâ fide?” I asked.

“Well, sir,” he replied, “my mates in the shop told me that you had been knighted, and that when a man was knighted he changed his name, and that you had taken that one.”

I need not say that my annoyance vanished, and that I laughed as heartily as his pals were probably doing round the corner.

A few of the problems which have come my way have been very similar to some which I had invented for the exhibition of the reasoning of Mr. Holmes. I might perhaps quote one in which that gentleman’s method of thought was copied with complete success. The case was as follows: A gentleman had disappeared. He had drawn a bank balance of £40 which was known to be on him. It was feared that he had been murdered for the sake of the money. He had last been heard of stopping at a large hotel in London, having come from the country that day. In the evening he went to a music-hall performance, came out of it about ten o’clock, returned to his hotel, changed his evening clothes, which were found in his room next day, and disappeared utterly. No one saw him leave the hotel, but a man occupying a neighbouring room declared that he had heard him moving during the night. A week had elapsed at the time that I was consulted, but the police had discovered nothing. Where was the man?

These were the whole of the facts as communicated to me by his relatives in the country. Endeavouring to see the matter through the eyes of Mr. Holmes, I answered by return mail that he was evidently either in Glasgow or in Edinburgh. It proved later that he had, as a fact, gone to Edinburgh, though in the week that had passed he had moved to another part of Scotland.

There I should leave the matter, for, as Dr. Watson has often shown, a solution explained is a mystery spoiled. At this stage the reader can lay down the book and show how simple it all is by working out the problem for himself. He has all the data which were ever given to me. For the sake of those, however, who have no turn for such conundrums, I will try to indicate the links which make the chain. The one advantage which I possessed was that I was familiar with the routine of London hotels—though I fancy it differs little from that of hotels elsewhere.

The first thing was to look at the facts and separate what was certain from what was conjecture. It was all certain except the statement of the person who heard the missing man in the night. How could he tell such a sound from any other sound in a large hotel? That point could be disregarded, if it traversed the general conclusions.

The first clear deduction was that the man had meant to disappear. Why else should he draw all his money? He had got out of the hotel during the night. But there is a night porter in all hotels, and it is impossible to get out without his knowledge when the door is once shut. The door is shut after the theatre-goers return—say at twelve o’clock. Therefore, the man left the hotel before twelve o’clock. He had come from the music-hall at ten, had changed his clothes, and had departed with his bag. No one had seen him do so. The inference is that he had done it at the moment when the hall was full of the returning guests, which is from eleven to eleven-thirty. After that hour, even if the door were still open, there are few people coming and going so that he with his bag would certainly have been seen.

Having got so far upon firm ground, we now ask ourselves why a man who desires to hide himself should go out at such an hour. If he intended to conceal himself in London he need never have gone to the hotel at all. Clearly then he was going to catch a train which would carry him away. But a man who is deposited by a train in any provincial station during the night is likely to be noticed, and he might be sure that when the alarm was raised and his description given, some guard or porter would remember him. Therefore, his destination would be some large town which he would reach as a terminus where all his fellow passengers would disembark and where he would lose himself in the crowd. When one turns up the time-table and sees that the great Scotch expresses bound for Edinburgh and Glasgow start about midnight, the goal is reached. As for his dress-suit, the fact that he abandoned it proved that he intended to adopt a line of life where there were no social amenities. This deduction also proved to be correct.

I quote such a case in order to show that the general lines of reasoning advocated by Holmes have a real practical application to life. In another case, where a girl had become engaged to a young foreigner who suddenly disappeared, I was able, by a similar process of deduction, to show her very clearly both whither he had gone and how unworthy he was of her affections.

On the other hand, these semi-scientific methods are occasionally laboured and slow as compared with the results of the rough-and-ready, practical man. Lest I should seem to have been throwing bouquets either to myself or to Mr. Holmes, let me state that on the occasion of a burglary of the village inn, within a stone-throw of my house, the village constable, with no theories at all, had seized the culprit while I had got no further than that he was a left-handed man with nails in his boots.

The unusual or dramatic effects which lead to the invocation of Mr. Holmes in fiction are, of course, great aids to him in reaching a conclusion. It is the case where there is nothing to get hold of which is the deadly one. I heard of such a one in America which would certainly have presented a formidable problem. A gentleman of blameless life starting off for a Sunday evening walk with his family, suddenly observed that he had forgotten something. He went back into the house, the door of which was still open, and he left his people waiting for him outside. He never reappeared, and from that day to this there has been no clue as to what befell him. This was certainly one of the strangest cases of which I have ever heard in real life.

Another very singular case came within my own observation. It was sent to me by an eminent London publisher. This gentleman had in his employment a head of department whose name we shall take as Musgrave. He was a hardworking person, with no special feature in his character. Mr. Musgrave died, and several years after his death a letter was received addressed to him, in the care of his employers. It bore the postmark of a tourist resort in the west of Canada, and had the note “Conflfilms” upon the outside of the envelope, with the words “Report Sy” in one corner.

The publishers naturally opened the envelope as they had no note of the dead man’s relatives. Inside were two blank sheets of paper. The letter, I may add, was registered. The publisher, being unable to make anything of this, sent it on to me, and I submitted the blank sheets to every possible chemical and heat test, with no result whatever. Beyond the fact that the writing appeared to be that of a woman there is nothing to add to this account. The matter was, and remains, an insoluble mystery. How the correspondent could have something so secret to say to Mr. Musgrave and yet not be aware that this person had been dead for several years is very hard to understand—or why blank sheets should be so carefully registered through the mail. I may add that I did not trust the sheets to my own chemical tests, but had the best expert advice without getting any result. Considered as a case it was a failure—and a very tantalizing one.

Mr. Sherlock Holmes has always been a fair mark for practical jokers, and I have had numerous bogus cases of various degrees of ingenuity, marked cards, mysterious warnings, cypher messages, and other curious communications. It is astonishing the amount of trouble which some people will take with no object save a mystification. Upon one occasion, as I was entering the hall to take part in an amateur billiard competition, I was handed by the attendant a small packet which had been left for me. Upon opening it I found a piece of ordinary green chalk such as is used in billiards. I was amused by the incident, and I put the chalk into my waistcoat pocket and used it during the game. Afterward, I continued to use it until one day, some months later, as I rubbed the tip of my cue the face of the chalk crumbled in, and I found it was hollow. From the recess thus exposed I drew out a small slip of paper with the words “From Arsene Lupin to Sherlock Holmes.”

Imagine the state of mind of the joker who took such trouble to accomplish such a result.

One of the mysteries submitted to Mr. Holmes was rather upon the psychic plane and therefore beyond his powers. The facts as alleged are most remarkable, though I have no proof of their truth save that the lady wrote earnestly and gave both her name and address. The person, whom we will call Mrs. Seagrave, had been given a curious secondhand ring, snake-shaped, and dull gold. This she took from her finger at night. One night she slept with it on and had a fearsome dream in which she seemed to be pushing off some furious creature which fastened its teeth into her arm. On awakening, the pain in the arm continued, and next day the imprint of a double set of teeth appeared upon the arm, with one tooth of the lower jaw missing. The marks were in the shape of blue-black bruises which had not broken the skin.

“I do not know,” says my correspondent, “what made me think the ring had anything to do with the matter, but I took a dislike to the thing and did not wear it for some months, when, being on a visit, I took to wearing it again.” To make a long story short, the same thing happened, and the lady settled the matter for ever by dropping her ring into the hottest corner of the kitchen range. This curious story, which I believe to be genuine, may not be as supernatural as it seems. It is well known that in some subjects a strong mental impression does produce a physical effect. Thus a very vivid nightmare dream with the impression of a bite might conceivably produce the mark of a bite. Such cases are well attested in medical annals. The second incident would, of course, arise by unconscious suggestion from the first. None the less, it is a very interesting little problem, whether psychic or material.

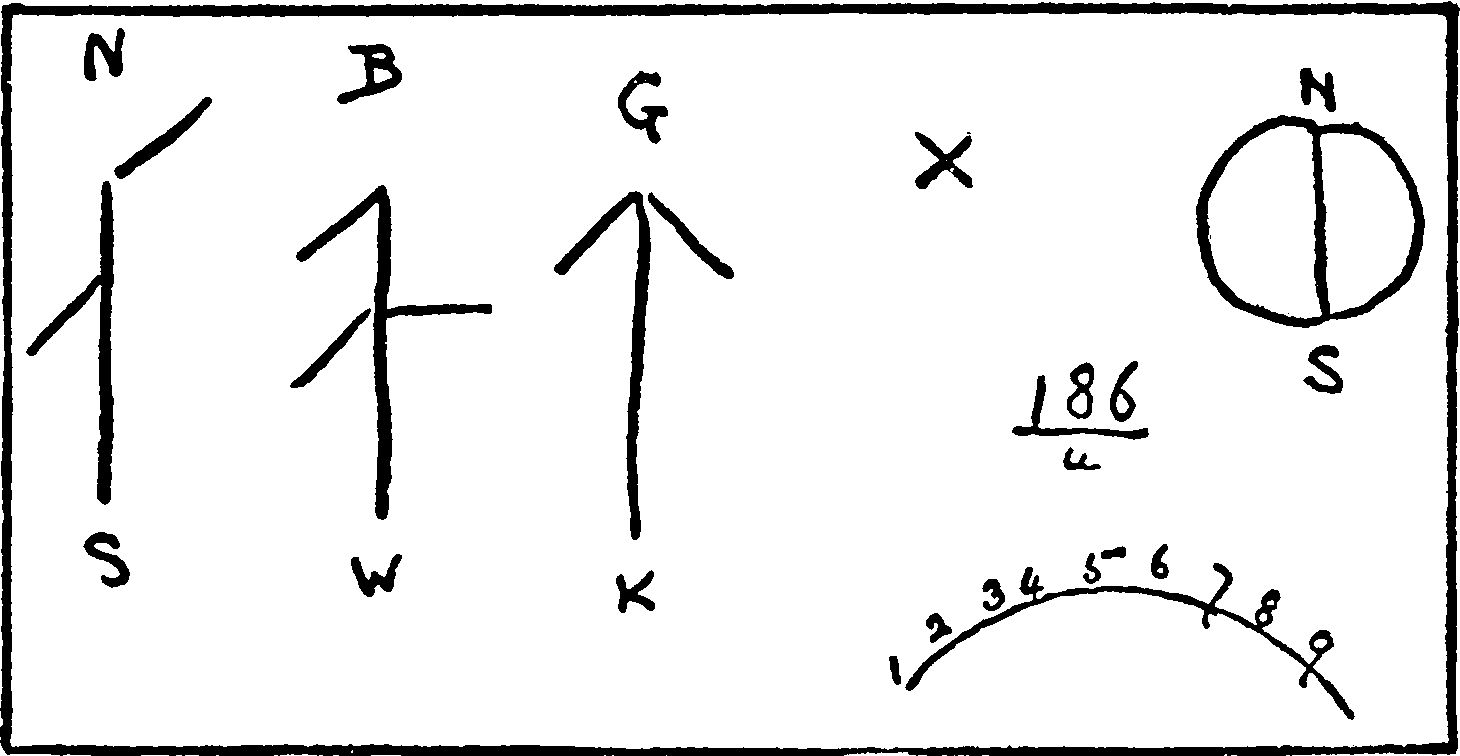

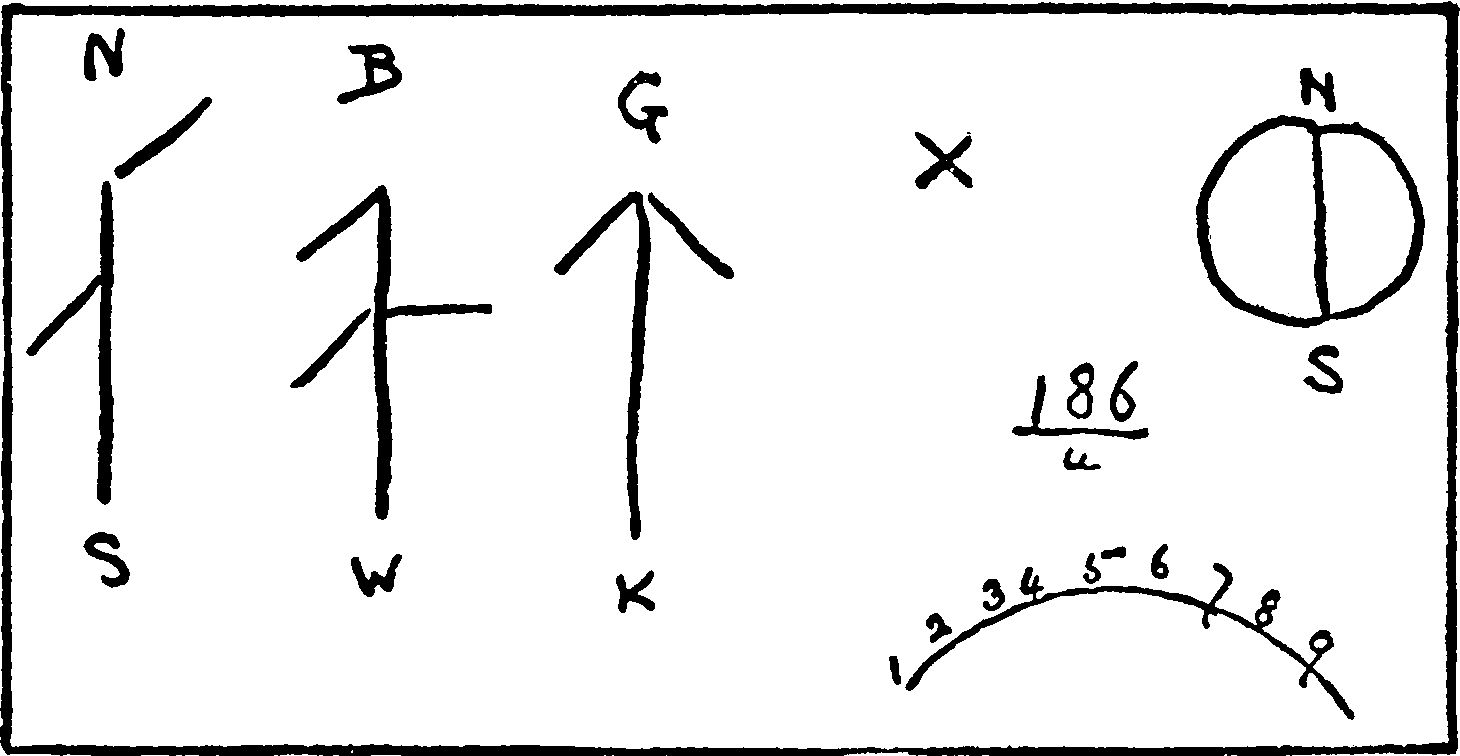

Buried treasures are naturally among the problems which have come to Mr. Holmes. One genuine case was accompanied by a diagram here reproduced. It refers to an Indiaman which was wrecked upon the South African coast in the year 1782. If I were a younger man, I should be seriously inclined to go personally and look into the matter.

The ship contained a remarkable treasure, including, I believe, the old crown regalia of Delhi. It is surmised that they buried these near the coast, and that this chart is a note of the spot. Each Indiaman in those days had its own semaphore code, and it is conjectured that the three marks upon the left are signals from a three-armed semaphore. Some record of their meaning might perhaps even now be found in the old papers of the India Office. The circle upon the right gives the compass bearings. The larger semi-circle may be the curved edge of a reef or of a rock. The figures above are the indications how to reach the X which marks the treasure. Possibly they may give the bearings as 186 feet from the 4 upon the semi-circle. The scene of the wreck is a lonely part of the country, but I shall be surprised if sooner or later, some one does not seriously set to work to solve the mystery—indeed at the present moment there is a small company working to that end.

I must now apologise for this digressive chapter and return to the orderly sequence of my career.