CHAPTER II

UNDER THE JESUITS

The Preparatory School—The Mistakes of Education—Spartan Schooling—Corporal Punishment—Well-known School Fellows—Gloomy Forecasts—Poetry—London Matriculation—German School—A Happy Year—The Jesuits—Strange Arrival in Paris.

I was in my tenth year when I was sent to Hodder, which is the preparatory school for Stonyhurst, the big Roman Catholic public school in Lancashire. It was a long journey for a little boy who had never been away from home before, and I felt very lonesome and wept bitterly upon the way, but in due time I arrived safely at Preston, which was then the nearest station, and with many other small boys and our black-robed Jesuit guardians we drove some twelve miles to the school. Hodder is about a mile from Stonyhurst, and as all the boys there are youngsters under twelve, it forms a very useful institution, breaking a lad into school ways before he mixes with the big fellows.

I had two years at Hodder. The year was not broken up by the frequent holidays which illuminate the present educational period. Save for six weeks each summer, one never left the school. On the whole, those first two years were happy years. I could hold my own both in brain and in strength with my comrades. I was fortunate enough to get under the care of a kindly principal, one Father Cassidy, who was more human than Jesuits usually are. I have always kept a warm remembrance of this man and of his gentle ways to the little boys—young rascals many of us—who were committed to his care. I remember the Franco-German War breaking out at this period, and how it made a ripple even in our secluded back-water.

From Hodder I passed on to Stonyhurst, that grand mediæval dwelling-house which was left some hundred and fifty years ago to the Jesuits, who brought over their whole teaching staff from some college in Holland in order to carry it on as a public school. The general curriculum, like the building, was mediæval but sound. I understand it has been modernized since. There were seven classes—elements, figures, rudiments, grammar, syntax, poetry and rhetoric—and you were allotted a year for each, or seven in all—a course with which I faithfully complied, two having already been completed at Hodder. It was the usual public school routine of Euclid, algebra and the classics, taught in the usual way, which is calculated to leave a lasting abhorrence of these subjects. To give boys a little slab of Virgil or Homer with no general idea as to what it is all about or what the classical age was like, is surely an absurd way of treating the subject. I am sure that an intelligent boy could learn more by reading a good translation of Homer for a week than by a year’s study of the original as it is usually carried out. It was no worse at Stonyhurst than at any other school, and it can only be excused on the plea that any exercise, however stupid in itself, forms a sort of mental dumb-bell by which one can improve one’s mind. It is, I think, a thoroughly false theory. I can say with truth that my Latin and Greek, which cost me so many weary hours, have been little use to me in life, and that my mathematics have been no use at all. On the other hand, some things which I picked up almost by accident, the art of reading aloud, learned when my mother was knitting, or the reading of French books, learned by spelling out the captions of the Jules Verne illustrations, have been of the greatest possible service. My classical education left me with a horror of the classics, and I was astonished to find how fascinating they were when I read them in a reasonable manner in later years.

Year by year, then, I see myself climbing those seven weary steps and passing through as many stages of my boyhood. I do not know if the Jesuit system of education is good or not; I would need to have tried another system as well before I could answer that. On the whole it was justified by results, for I think it turned out as decent a set of young fellows as any other school would do. In spite of a large infusion of foreigners and some disaffected Irish, we were a patriotic crowd, and our little pulse beat time with the heart of the nation. I am told that the average of V.C.’s and D.S.O.’s now held by old Stonyhurst boys is very high as compared with other schools. The Jesuit teachers have no trust in human nature, and perhaps they are justified. We were never allowed for an instant to be alone with each other, and I think that the immorality which is rife in public schools was at a minimum in consequence. In our games and our walks the priests always took part, and a master perambulated the dormitories at night. Such a system may weaken self-respect and self-help, but it at least minimizes temptation and scandal.

The life was Spartan, and yet we had all that was needed. Dry bread and hot well-watered milk were our frugal breakfast. There was a “joint” and twice a week a pudding for dinner. Then there was an odd snack called “bread and beer” in the afternoon, a bit of dry bread and the most extraordinary drink, which was brown but had no other characteristic of beer. Finally, there was hot milk again, bread, butter, and often potatoes for supper. We were all very healthy on this régime, on Fridays. Everything in every way was plain to the verge of austerity, save that we dwelt in a beautiful building, dined in a marble-floored hall with minstrels’ gallery, prayed in a lovely church, and generally lived in very choice surroundings so far as vision and not comfort was concerned.

Corporal punishment was severe, and I can speak with feeling as I think few, if any, boys of my time endured more of it. It was of a peculiar nature, imported also, I fancy, from Holland. The instrument was a piece of india-rubber of the size and shape of a thick boot sole. This was called a “Tolley”—why, no one has explained, unless it is a Latin pun on what we had to bear. One blow of this instrument, delivered with intent, would cause the palm of the hand to swell up and change colour. When I say that the usual punishment of the larger boys was nine on each hand, and that nine on one hand was the absolute minimum, it will be understood that it was a severe ordeal, and that the sufferer could not, as a rule, turn the handle of the door to get out of the room in which he had suffered. To take twice nine upon a cold day was about the extremity of human endurance. I think, however, that it was good for us in the end, for it was a point of honour with many of us not to show that we were hurt, and that is one of the best trainings for a hard life. If I was more beaten than others it was not that I was in any way vicious, but it was that I had a nature which responded eagerly to affectionate kindness (which I never received), but which rebelled against threats and took a perverted pride in showing that it would not be cowed by violence. I went out of my way to do really mischievous and outrageous things simply to show that my spirit was unbroken. An appeal to my better nature and not to my fears would have found an answer at once. I deserved all I got for what I did, but I did it because I was mishandled.

I do not remember any one who attained particular distinction among my school-fellows, save Bernard Partridge of “Punch,” whom I recollect as a very quiet, gentle boy. Father Thurston, who was destined to be one of my opponents in psychic matters so many years later, was in the class above me. There was a young novice, too, with whom I hardly came in contact, but whose handsome and spiritual appearance I well remember. He was Bernard Vaughan, afterwards the famous preacher. Save for one school-fellow, James Ryan—a remarkable boy who grew into a remarkable man—I carried away no lasting friendship from Stonyhurst.

It was only in the latest stage of my Stonyhurst development that I realized that I had some literary streak in me which was not common to all. It came to me as quite a surprise, and even more perhaps to my masters, who had taken a rather hopeless view of my future prospects. One master, when I told him that I thought of being a civil engineer, remarked, “Well, Doyle, you may be an engineer, but I don’t think you will ever be a civil one.” Another assured me that I would never do any good in the world, and perhaps from his point of view his prophecy has been justified. The particular incident, however, which brought my latent powers to the surface depended upon the fact that in the second highest class, which I reached in 1874, it was incumbent to write poetry (so called) on any theme given. This was done as a dreary unnatural task by most boys. Very comical their wooings of the muses used to be. For one saturated as I really was with affection for verse, it was a labour of love, and I produced verses which were poor enough in themselves but seemed miracles to those who had no urge in that direction. The particular theme was the crossing of the Red Sea by the Israelites and my effort from—

“Like pallid daisies in a grassy wood,

So round the sward the tents of Israel stood”;

through—

“There was no time for thought and none for fear,

For Egypt’s horse already pressed their rear.”

down to the climax—

“One horrid cry! The tragedy was o’er,

And Pharaoh with his army seen no more,”—

was workmanlike though wooden and conventional. Anyhow, it marked what Mr. Stead used to call a signpost, and I realized myself a little. In the last year I edited the College magazine and wrote a good deal of indifferent verse. I also went up for the Matriculation examination of London University, a good all-round test which winds up the Stonyhurst curriculum, and I surprised every one by taking honours, so after all I emerged from Stonyhurst at the age of sixteen with more credit than seemed probable from my rather questionable record.

Early in my career there, an offer had been made to my mother that my school fees would be remitted if I were dedicated to the Church. She refused this, so both the Church and I had an escape. When I think, however, of her small income and great struggle to keep up appearances and make both ends meet, it was a fine example of her independence of character, for it meant paying out some £50 a year which might have been avoided by a word of assent.

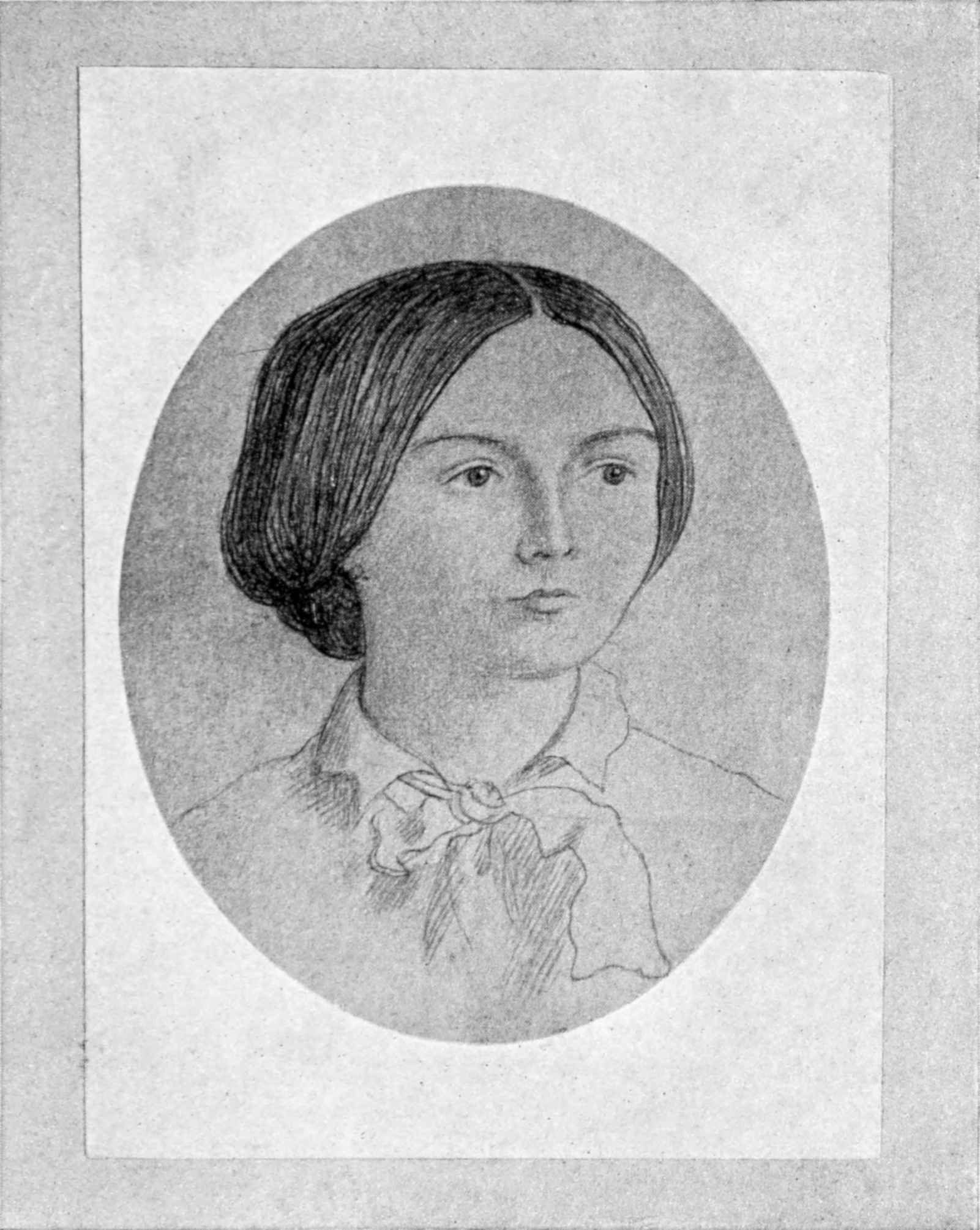

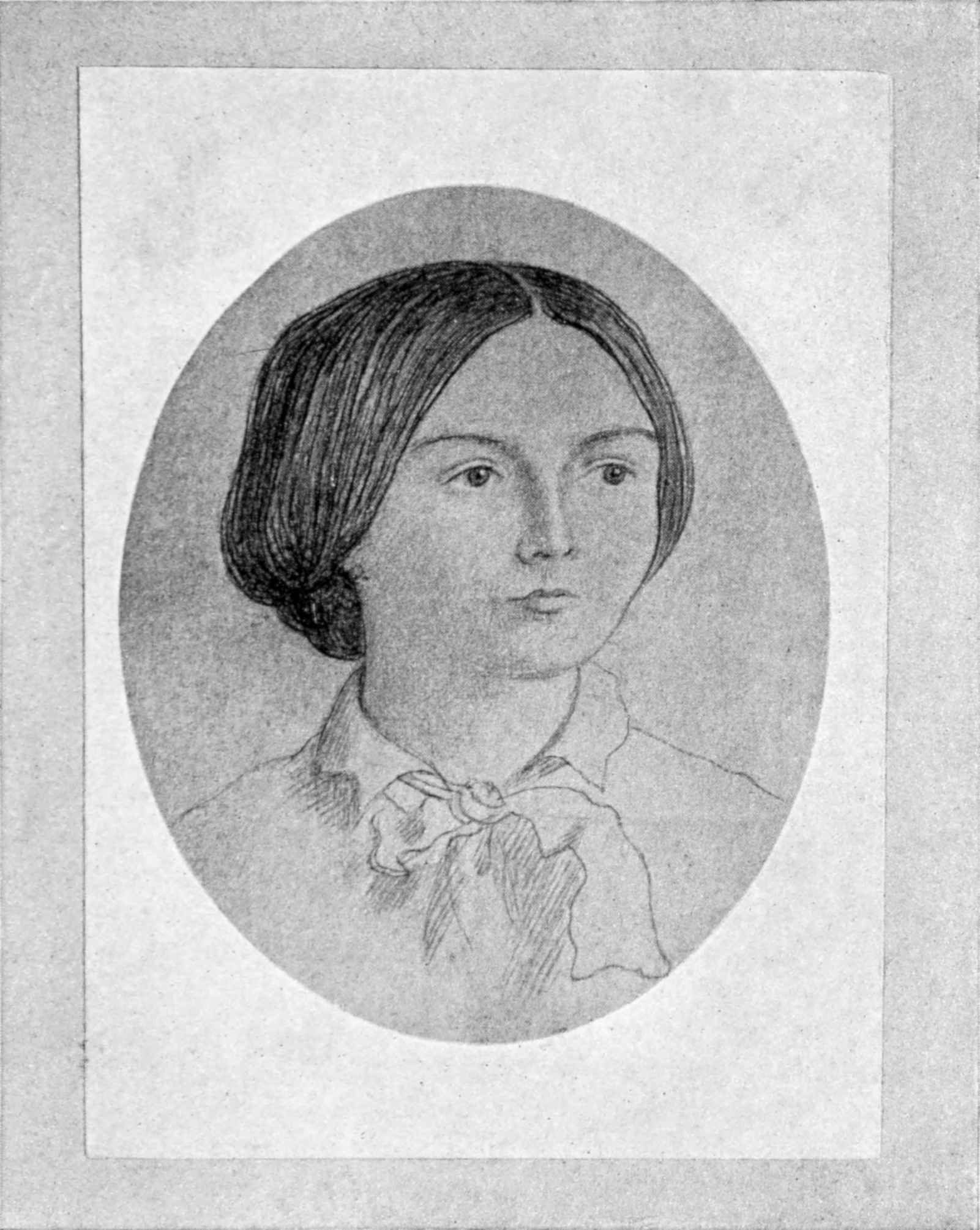

MY MOTHER, AT 17.

Drawn by Richard Doyle, July 1854.

I had yet another year with the Jesuits, for it was determined that I was still too young to begin any professional studies, and that I should go to Germany and learn German. I was despatched, therefore, to Feldkirch, which is a Jesuit school in the Vorarlberg province of Austria, to which many better-class German boys are sent. Here the conditions were much more humane and I met with far more human kindness than at Stonyhurst, with the immediate result that I ceased to be a resentful young rebel and became a pillar of law and order.

I began badly, however, for on the first night of my arrival I was kept awake by a boy snoring loudly in the dormitory. I stood it as long as I could, but at last I was driven to action. Curious wooden compasses called bett-scheere, or “bed-scissors,” were stuck into each side of the narrow beds. One of these I plucked out, walked down the dormitory, and, having spotted the offender, proceeded to poke him with my stick. He awoke and was considerably amazed to see in the dim light a large youth whom he had never seen before—I arrived after hours—assaulting him with a club. I was still engaged in stirring him up when I felt a touch on my shoulder and was confronted by the master, who ordered me back to bed. Next morning I got a lecture on free-and-easy English ways, and taking the law into my own hands. But this start was really my worst lapse and I did well in the future.

It was a happy year on the whole. I made less progress with German than I should, for there were about twenty English and Irish boys who naturally balked the wishes of their parents by herding together. There was no cricket, but there were toboganning and fair football and a weird game—football on stilts. Then there were the lovely mountains round us, with an occasional walk among them. The food was better than at Stonyhurst and we had the pleasant German light beer instead of the horrible swipes of Stonyhurst. One unlooked-for accomplishment I acquired, for the boy who played the big brass bass instrument in the fine school band had not returned, and, as a well-grown lad was needed, I was at once enlisted in the service. I played in public—good music, too, “Lohengrin,” and “Tannhäuser,”—within a week or two of my first lesson, but they pressed me on for the occasion and the Bombardon, as it was called, only comes in on a measured rhythm with an occasional run, which sounds like a hippopotamus doing a step-dance. So big was the instrument that I remember the other bandsmen putting my sheets and blankets inside it and my surprise when I could not get out a note. It was in the summer of 1876 that I left Feldkirch, and I have always had a pleasant memory of the Austrian Jesuits and of the old schools.

Indeed I have a kindly feeling towards all Jesuits, far as I have strayed from their paths. I see now both their limitations and their virtues. They have been slandered in some things, for during eight years of constant contact I cannot remember that they were less truthful than their fellows, or more casuistical than their neighbours. They were keen, clean-minded earnest men, so far as I knew them, with a few black sheep among them, but not many, for the process of selection was careful and long. In all ways, save in their theology, they were admirable, though this same theology made them hard and inhuman upon the surface, which is indeed the general effect of Catholicism in its more extreme forms. The convert is lost to the family. Their hard, narrow outlook gives the Jesuits driving power, as is noticeable in the Puritans and all hard, narrow creeds. They are devoted and fearless and have again and again, both in Canada, in South America and in China, been the vanguard of civilization to their own grievous hurt. They are the old guard of the Roman Church. But the tragedy is that they, who would gladly give their lives for the old faith, have in effect helped to ruin it, for it is they, according to Father Tyrrell and the modernists, who have been at the back of all those extreme doctrines of papal infallibility and Immaculate Conception, with a general all-round tightening of dogma, which have made it so difficult for the man with scientific desire for truth or with intellectual self-respect to keep within the Church. For some years Sir Charles Mivart, the last of Catholic Scientists, tried to do the impossible, and then he also had to leave go his hold, so that there is not, so far as I know, one single man of outstanding fame in science or in general thought who is a practising Catholic. This is the work of the extremists and is deplored by many of the moderates and fiercely condemned by the modernists. It depends also upon the inner Italian directorate who give the orders. Nothing can exceed the uncompromising bigotry of the Jesuit theology, or their apparent ignorance of how it shocks the modern conscience. I remember that when, as a grown lad, I heard Father Murphy, a great fierce Irish priest, declare that there was sure damnation for every one outside the Church, I looked upon him with horror, and to that moment I trace the first rift which has grown into such a chasm between me and those who were my guides.

On my way back to England I stopped at Paris. Through all my life up to this point there had been an unseen granduncle, named Michael Conan, to whom I must now devote a paragraph. He came into the family from the fact that my father’s father (“H. B.”) had married a Miss Conan. Michael Conan, her brother, had been editor of “The Art Journal” and was a man of distinction, an intellectual Irishman of the type which originally founded the Sinn Fein movement. He was as keen on heraldry and genealogy as my mother, and he traced his descent in some circuitous way from the Dukes of Brittany, who were all Conans; indeed Arthur Conan was the ill-fated young Duke whose eyes were put out, according to Shakespeare, by King John. This uncle was my godfather, and hence my name Arthur Conan.

He lived in Paris and had expressed a wish that his grandnephew and godson, with whom he had corresponded, should call en passant. I ran my money affairs so closely, after a rather lively supper at Strasburg, that when I reached Paris I had just twopence in my pocket. As I could not well drive up and ask my uncle to pay the cab I left my trunk at the station and set forth on foot. I reached the river, walked along it, came to the foot of the Champs Élysées, saw the Arc de Triomphe in the distance, and then, knowing that the Avenue Wagram, where my uncle lived, was near there, I tramped it on a hot August day and finally found him. I remember that I was exhausted with the heat and the walking, and that when at the last gasp I saw a man buy a drink of what seemed to be porter by handing a penny to a man who had a long tin on his back, I therefore halted the man and spent one of my pennies on a duplicate drink. It proved to be liquorice and water, but it revived me when I badly needed it, and it could not be said that I arrived penniless at my uncle’s, for I actually had a penny.

So, for some penurious weeks, I was in Paris with this dear old volcanic Irishman, who spent the summer day in his shirt-sleeves, with a little dicky-bird of a wife waiting upon him. I am built rather on his lines of body and mind than on any of the Doyles. We made a true friendship, and then I returned to my home conscious that real life was about to begin.