CHAPTER IV

WHALING IN THE ARCTIC OCEAN

The Hope—John Gray—Boxing—The Terrible Mate—Our Criminal—First Sight of a Woman—A Hurricane—Dangers of the Fishing—Three Dips in the Arctic—The Idlers’ Boat—Whale Taking—Glamour of the Arctic—Effect of Voyage.

It was in the Hope, under the command of the well-known whaler, John Gray, that I paid a seven months’ visit to the Arctic Seas in the year 1880. I went in the capacity of surgeon, but as I was only twenty years of age when I started, and as my knowledge of medicine was that of an average third year’s student, I have often thought that it was as well that there was no very serious call upon my services.

It came about in this way. One raw afternoon in Edinburgh, whilst I was sitting reading hard for one of those examinations which blight the life of a medical student, there entered to me one Currie, a fellow-student with whom I had some slight acquaintance. The monstrous question which he asked drove all thought of my studies out of my head.

“Would you care,” said he, “to start next week for a whaling cruise? You’ll be surgeon, two pound ten a month and three shillings a ton oil money.”

“How do you know I’ll get the berth?” was my natural question.

“Because I have it myself. I find at this last moment that I can’t go, and I want to get a man to take my place.”

“How about an Arctic kit?”

“You can have mine.”

In an instant the thing was settled, and within a few minutes the current of my life had been deflected into a new channel.

In little more than a week I was in Peterhead, and busily engaged, with the help of the steward, in packing away my scanty belongings in the locker beneath my bunk on the good ship Hope.

I speedily found that the chief duty of the surgeon was to be the companion of the captain, who is cut off by the etiquette of the trade from anything but very brief and technical talks with his other officers. I should have found it intolerable if the captain had been a bad fellow, but John Gray of the Hope was a really splendid man, a grand seaman and a serious-minded Scot, so that he and I formed a comradeship which was never marred during our long tête-à-tête. I see him now, his ruddy face, his grizzled hair and beard, his very light blue eyes always looking into far spaces, and his erect muscular figure. Taciturn, sardonic, stern on occasion, but always a good just man at bottom.

There was one curious thing about the manning of the Hope. The man who signed on as first mate was a little, decrepit, broken fellow, absolutely incapable of performing the duties. The cook’s assistant, on the other hand, was a giant of a man, red-bearded, bronzed, with huge limbs, and a voice of thunder. But the moment that the ship cleared the harbour the little, decrepit mate disappeared into the cook’s galley, and acted as scullery-boy for the voyage, while the mighty scullery-boy walked aft and became chief mate. The fact was, that the one had the certificate, but was past sailoring, while the other could neither read nor write, but was as fine a seaman as ever lived; so, by an agreement to which everybody concerned was party, they swapped their berths when they were at sea.

Colin McLean, with his six foot of stature, his erect, stalwart figure, and his fierce, red beard, pouring out from between the flaps of his sealing-cap, was an officer by natural selection, which is a higher title than that of a Board of Trade certificate. His only fault was that he was a very hot-blooded man, and that a little would excite him to a frenzy. I have a vivid recollection of an evening which I spent in dragging him off the steward, who had imprudently made some criticism upon his way of attacking a whale which had escaped. Both men had had some rum, which had made the one argumentative and the other violent, and as we were all three seated in a space of about seven by four, it took some hard work to prevent bloodshed. Every now and then, just as I thought all danger was past, the steward would begin again with his fatuous, “No offence, Colin, but all I says is that if you had been a bit quicker on the fush——” I don’t know how often this sentence was begun, but never once was it ended; for at the word “fush” Colin always seized him by the throat, and I Colin round the waist, and we struggled until we were all panting and exhausted. Then when the steward had recovered a little breath he would start that miserable sentence once more, and the “fush” would be the signal for another encounter. I really believe that if I had not been there the mate would have hurt him, for he was quite the angriest man that I have ever seen.

There were fifty men upon our whaler, of whom half were Scotchmen and half Shetlanders, whom we picked up at Lerwick as we passed. The Shetlanders were the steadier and more tractable, quiet, decent, and soft-spoken; while the Scotch seamen were more likely to give trouble, but also more virile and of stronger character. The officers and harpooners were all Scotch, but as ordinary seamen, and especially as boatmen, the Shetlanders were as good as could be wished.

There was only one man on board who belonged neither to Scotland nor to Shetland, and he was the mystery of the ship. He was a tall, swarthy, dark-eyed man, with blue-black hair and beard, singularly handsome features, and a curious, reckless sling of his shoulders when he walked. It was rumoured that he came from the south of England, and that he had fled thence to avoid the law. He made friends with no one, and spoke very seldom, but he was one of the smartest seamen in the ship. I could believe from his appearance that his temper was Satanic, and that the crime for which he was hiding may have been a bloody one. Only once he gave us a glimpse of his hidden fires. The cook—a very burly, powerful man—the little mate was only assistant—had a private store of rum, and treated himself so liberally to it that for three successive days the dinner of the crew was ruined. On the third day our silent outlaw approached the cook with a brass saucepan in his hand. He said nothing, but he struck the man such a frightful blow that his head flew through the bottom and the sides of the pan were left dangling round his neck. The half-drunken, half-stunned cook talked of fighting, but he was soon made to feel that the sympathy of the ship was against him, so he reeled back, grumbling, to his duties while the avenger relapsed into his usual moody indifference. We heard no further complaints of the cooking.

I have spoken of the steward, and as I look back at that long voyage, during which for seven months we never set foot on land, the kindly open face of Jack Lamb comes back to me. He had a beautiful and sympathetic tenor voice, and many an hour have I listened to it with its accompaniment of rattling plates and jingling knives, as he cleaned up the dishes in his pantry. He had a great memory for pathetic and sentimental songs, and it is only when you have not seen a woman’s face for six months that you realize what sentiment means. When Jack trilled out “Her bright smile haunts me still,” or “Wait for me at Heaven’s Gate, sweet Belle Mahone,” he filled us all with a vague sweet discontent which comes back to me now as I think of it. To appreciate a woman one has to be out of sight of one for six months. I can well remember that as we rounded the north of Scotland on our return we dipped our flag to the lighthouse, being only some hundreds of yards from the shore. A figure emerged to answer our salute, and the excited whisper ran through the ship, “It’s a wumman!” The captain was on the bridge with his telescope. I had the binoculars in the bows. Every one was staring. She was well over fifty, short skirts and sea boots—but she was a “wumman.” “Anything in a mutch!” the sailors used to say, and I was of the same way of thinking.

However, all this has come before its time. It was, I find by my log, on February 28 at 2 p.m. that we sailed from Peterhead, amid a great crowd and uproar. The decks were as clean as a yacht, and it was very unlike my idea of a whaler. We ran straight into bad weather and the glass went down at one time to 28.375, which is the lowest reading I can remember in all my ocean wanderings. We just got into Lerwick Harbour before the full force of the hurricane broke, which was so great that lying at anchor with bare poles and partly screened we were blown over to an acute angle. If it had taken us a few hours earlier we should certainly have lost our boats—and the boats are the life of a whaler. It was March 11 before the weather moderated enough to let us get on, and by that time there were twenty whalers in the bay, so that our setting forth was quite an occasion. That night and for a day longer the Hope had to take refuge in the lee of one of the outlying islands. I got ashore and wandered among peat bogs, meeting strange, barbarous, kindly people who knew nothing of the world. I was led back to the ship by a wild, long-haired girl holding a torch, for the peat holes make it dangerous at night—I can see her now, her tangled black hair, her bare legs, madder-stained petticoat, and wild features under the glare of the torch. I spoke to one old man there who asked me the news. I said, “The Tay bridge is down,” which was then a fairly stale item. He said, “Eh, have they built a brig over the Tay?” After that I felt inclined to tell him about the Indian Mutiny.

What surprised me most in the Arctic regions was the rapidity with which you reach them. I had never realized that they lie at our very doors. I think that we were only four days out from Shetland when we were among the drift ice. I awoke one morning to hear the bump, bump of the floating pieces against the side of the ship, and I went on deck to see the whole sea covered with them to the horizon. They were none of them large, but they lay so thick that a man might travel far by springing from one to the other. Their dazzling whiteness made the sea seem bluer by contrast, and with a blue sky above, and that glorious Arctic air in one’s nostrils, it was a morning to remember. Once on one of the swaying, rocking pieces we saw a huge seal, sleek, sleepy, and imperturbable, looking up with the utmost assurance at the ship, as if it knew that the close time had still three weeks to run. Further on we saw on the ice the long human-like prints of a bear. All this with the snowdrops of Scotland still fresh in our glasses in the cabin.

I have spoken about the close time, and I may explain that, by an agreement between the Norwegian and British Governments, the subjects of both nations are forbidden to kill a seal before April 3. The reason for this is that the breeding season is in March, and if the mothers should be killed before the young are able to take care of themselves, the race would soon become extinct. For breeding purposes the seals all come together at a variable spot, which is evidently pre-arranged among them, and as this place can be anywhere within many hundreds of square miles of floating ice, it is no easy matter for the fisher to find it. The means by which he sets about it are simple but ingenious. As the ship makes its way through the loose ice-streams, a school of seals is observed travelling through the water. Their direction is carefully taken by compass and marked upon the chart. An hour afterwards perhaps another school is seen. This is also marked. When these bearings have been taken several times, the various lines upon the chart are prolonged until they intersect. At this point, or near it, it is likely that the main pack of the seals will be found.

When you do come upon it, it is a wonderful sight. I suppose it is the largest assembly of creatures upon the face of the world—and this upon the open icefields hundreds of miles from the Greenland coast. Somewhere between 71 deg. and 75 deg. is the rendezvous, and the longitude is even vaguer; but the seals have no difficulty in finding the address. From the crow’s nest at the top of the main-mast, one can see no end of them. On the furthest visible ice one can still see that sprinkling of pepper grains. And the young lie everywhere also, snow-white slugs, with a little black nose and large dark eyes. Their half-human cries fill the air; and when you are sitting in the cabin of a ship which is in the heart of the seal-pack, you would think you were next door to a monstrous nursery.

The Hope was one of the first to find the seal-pack that year, but before the day came when hunting was allowed, we had a succession of strong gales, followed by a severe roll, which tilted the floating ice and launched the young seals prematurely into the water. And so, when the law at last allowed us to begin work, Nature had left us with very little work to do. However, at dawn upon the third, the ship’s company took to the ice, and began to gather in its murderous harvest. It is brutal work, though not more brutal than that which goes on to supply every dinner-table in the country. And yet those glaring crimson pools upon the dazzling white of the icefields, under the peaceful silence of a blue Arctic sky, did seem a horrible intrusion. But an inexorable demand creates an inexorable supply, and the seals, by their death, help to give a living to the long line of seamen, dockers, tanners, curers, triers, chandlers, leather merchants, and oil-sellers, who stand between this annual butchery on the one hand, and the exquisite, with his soft leather boots, or the savant, using a delicate oil for his philosophical instruments, upon the other.

I have cause to remember that first day of sealing on account of the adventures which befell me. I have said that a strong swell had arisen, and as this was dashing the floating ice together the captain thought it dangerous for an inexperienced man to venture upon it. And so, just as I was clambering over the bulwarks with the rest, he ordered me back and told me to remain on board. My remonstrances were useless, and at last, in the blackest of tempers, I seated myself upon the top of the bulwarks, with my feet dangling over the outer side, and there I nursed my wrath, swinging up and down with the roll of the ship. It chanced, however, that I was really seated upon a thin sheet of ice which had formed upon the wood, and so when the swell threw her over to a particularly acute angle, I shot off and vanished into the sea between two ice-blocks. As I rose, I clawed on to one of these, and soon scrambled on board again. The accident brought about what I wished, however, for the captain remarked that as I was bound to fall into the ocean in any case, I might just as well be on the ice as on the ship. I justified his original caution by falling in twice again during the day, and I finished it ignominiously by having to take to my bed while all my clothes were drying in the engine-room. I was consoled for my misfortunes by finding that they amused the captain to such an extent that they drove the ill-success of our sealing out of his head, and I had to answer to the name of “the great northern diver” for a long time thereafter. I had a narrow escape once through stepping backwards over the edge of a piece of floating ice while I was engaged in skinning a seal. I had wandered away from the others, and no one saw my misfortune. The face of the ice was so even that I had no purchase by which to pull myself up, and my body was rapidly becoming numb in the freezing water. At last, however, I caught hold of the hind flipper of the dead seal, and there was a kind of nightmare tug-of-war, the question being whether I should pull the seal off or pull myself on. At last, however, I got my knee over the edge and rolled on to it. I remember that my clothes were as hard as a suit of armour by the time I reached the ship, and that I had to thaw my crackling garments before I could change them.

This April sealing is directed against the mothers and young. Then, in May, the sealer goes further north, and about latitude 77 deg. or 78 deg. he comes upon the old male seals, who are by no means such easy victims. They are wary creatures, and it takes good long-range shooting to bag them. Then, in June, the sealing is over, and the ship bears away further north still, until in the 79th or 80th degree she is in the best Greenland whaling latitudes. There we stayed for three months or so, with very varying fortunes, for though we pursued many whales, only four were slain.

There are eight boats on board a whaler, but it is usual to send out only seven, for it takes six men to man each, so that when seven are out no one is left on board save the so-called “idlers” who have not signed to do seaman’s work at all. It happened, however, that aboard the Hope the idlers were rather a hefty crowd, so we volunteered to man the odd boat, and we made it, in our own estimation at least, one of the most efficient, both in sealing and in whaling. The steward, the second engineer, the donkey-engine man, and I were the oars, with a red-headed Highlander for harpooner and the handsome outlaw to steer. Our tally of seals was high, and in whaling we were once the lancing and once the harpooning boat, so our record was good. So congenial was the work to me that Captain Gray was good enough to offer to make me harpooner as well as surgeon, with the double pay, if I would come with him on a second voyage. It is well that I refused, for the life is dangerously fascinating.

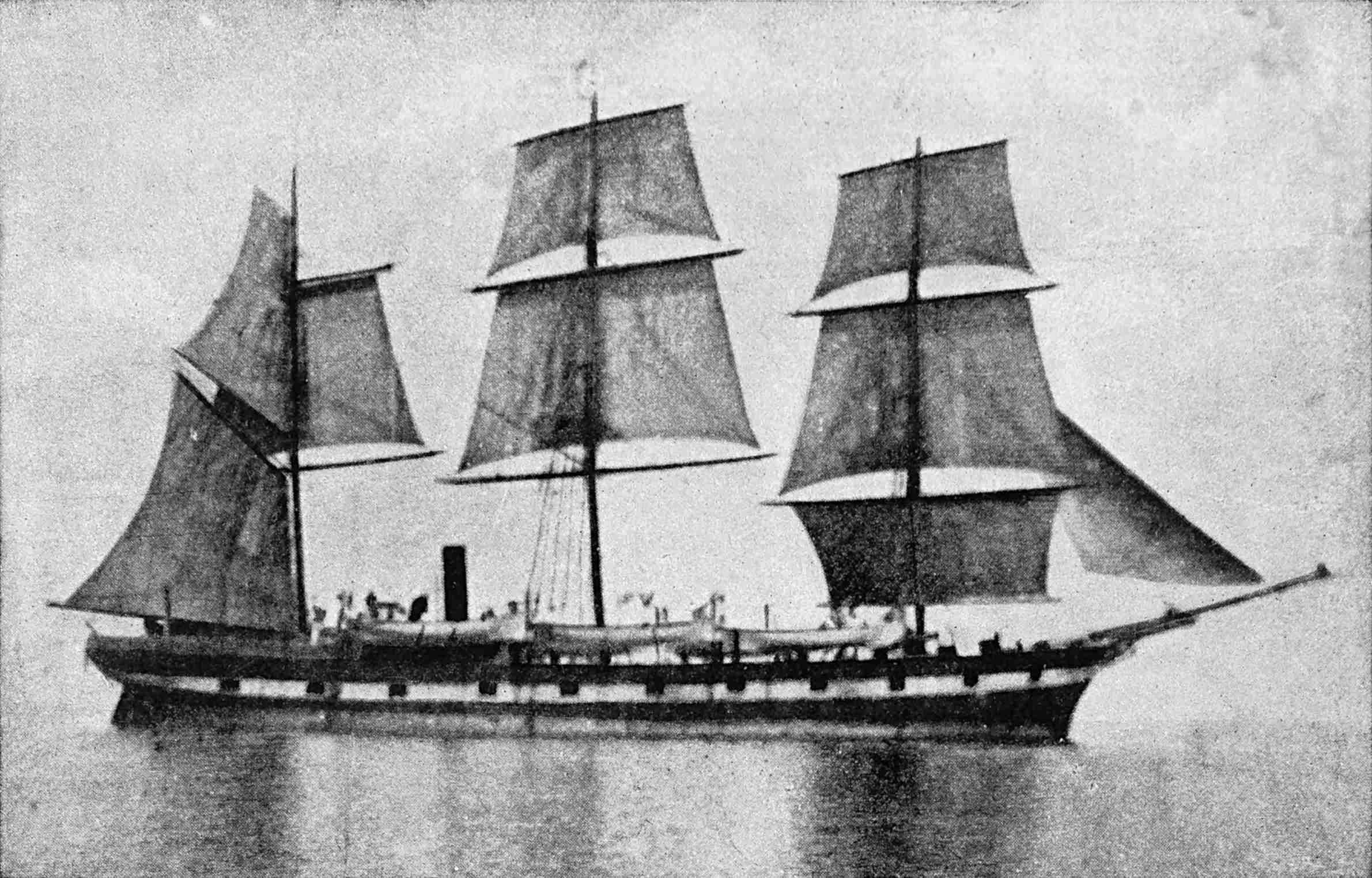

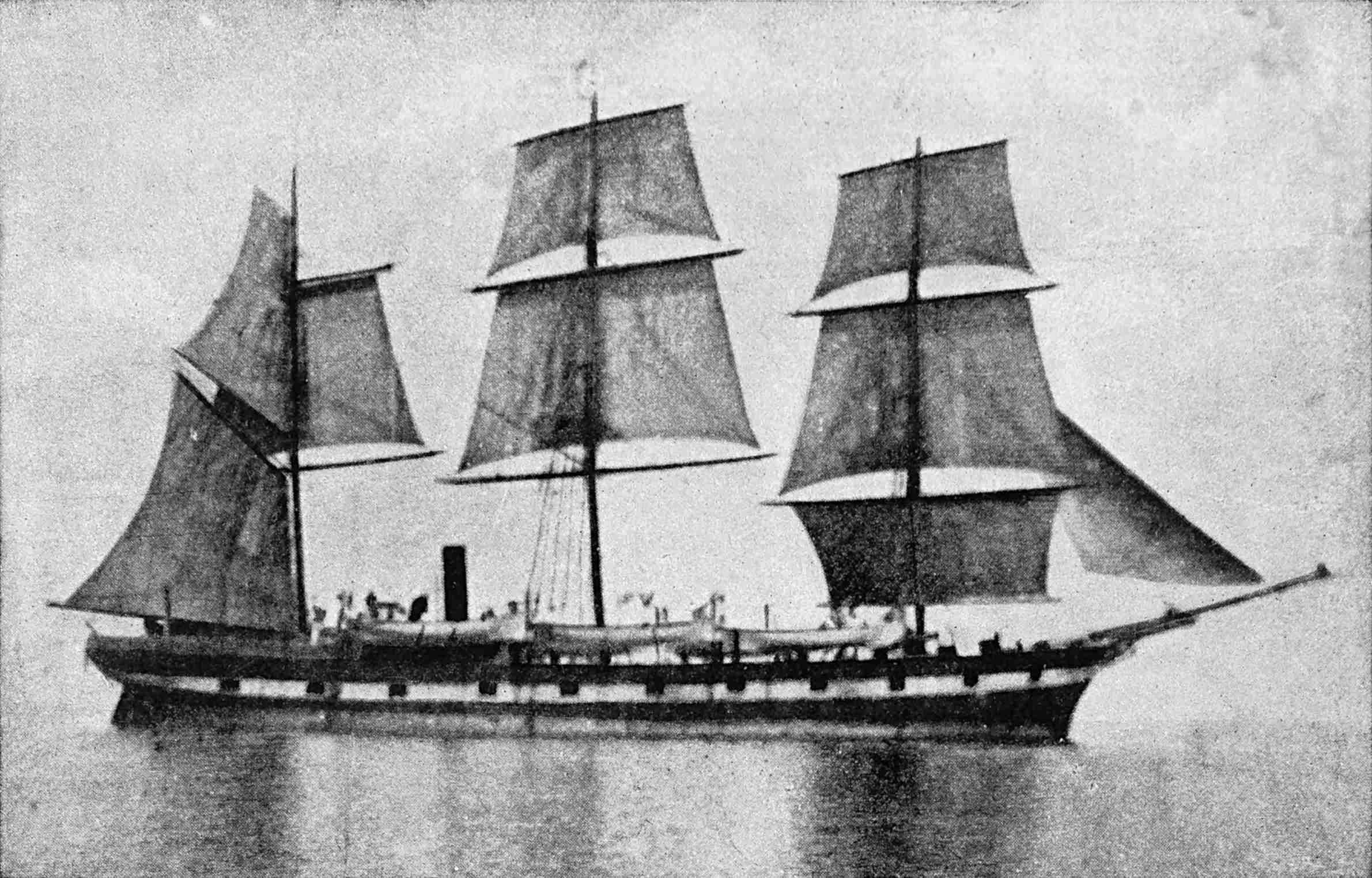

STEAM-WHALER “HOPE.”

It is exciting work pulling on to a whale. Your own back is turned to him, and all you know about him is what you read upon the face of the boat-steerer. He is staring out over your head, watching the creature as it swims slowly through the water, raising his hand now and again as a signal to stop rowing when he sees that the eye is coming round, and then resuming the stealthy approach when the whale is end on. There are so many floating pieces of ice, that as long as the oars are quiet the boat alone will not cause the creature to dive. So you creep slowly up, and at last you are so near that the boat-steerer knows that you can get there before the creature has time to dive—for it takes some little time to get that huge body into motion. You see a sunken gleam in his eyes, and a flush in his cheeks, and it’s “Give way, boys! Give way, all! Hard!” Click goes the trigger of the big harpoon gun, and the foam flies from your oars. Six strokes, perhaps, and then with a dull greasy squelch the bows run upon something soft, and you and your oars are sent flying in every direction. But little you care for that, for as you touched the whale you have heard the crash of the gun, and know that the harpoon has been fired point-blank into the huge, lead-coloured curve of its side. The creature sinks like a stone, the bows of the boat splash down into the water again, but there is the little red Jack flying from the centre thwart to show that you are fast, and there is the line whizzing swiftly under the seats and over the bows between your outstretched feet.

And this is the great element of danger—for it is rarely indeed that the whale has spirit enough to turn upon its enemies. The line is very carefully coiled by a special man named the line-coiler, and it is warranted not to kink. If it should happen to do so, however, and if the loop catches the limbs of any one of the boat’s crew, that man goes to his death so rapidly that his comrades hardly know that he has gone. It is a waste of fish to cut the line, for the victim is already hundreds of fathoms deep.

“Haud your hand, mon,” cried the harpooner, as a seaman raised his knife on such an occasion. “The fush will be a fine thing for the widdey.” It sounds callous, but there was philosophy at the base of it.

This is the harpooning, and that boat has no more to do. But the lancing, when the weary fish is killed with the cold steel, is a more exciting because it is a more prolonged experience. You may be for half an hour so near to the creature that you can lay your hand upon its slimy side. The whale appears to have but little sensibility to pain, for it never winces when the long lances are passed through its body. But its instinct urges it to get its tail to work on the boats, and yours urges you to keep poling and boat-hooking along its side, so as to retain your safe position near its shoulder. Even there, however, we found on one occasion that we were not quite out of danger’s way, for the creature in its flurry raised its huge-side-flapper and poised it over the boat. One flap would have sent us to the bottom of the sea, and I can never forget how, as we pushed our way from under, each of us held one hand up to stave off that great, threatening fin—as if any strength of ours could have availed if the whale had meant it to descend. But it was spent with loss of blood, and instead of coming down the fin rolled over the other way, and we knew that it was dead. Who would swap that moment for any other triumph that sport can give?

The peculiar other-world feeling of the Arctic regions—a feeling so singular that if you have once been there the thought of it haunts you all your life—is due largely to the perpetual daylight. Night seems more orange-tinted and subdued than day, but there is no great difference. Some captains have been known to turn their hours right round out of caprice, with breakfast at night and supper at ten in the morning. There are your twenty-four hours, and you may carve them as you like. After a month or two the eyes grow weary of the eternal light, and you appreciate what a soothing thing our darkness is. I can remember as we came abreast of Iceland, on our return, catching our first glimpse of a star, and being unable to take my eyes from it, it seemed such a dainty little twinkling thing. Half the beauties of Nature are lost through over-familiarity.

Your sense of loneliness also heightens the effect of the Arctic Seas. When we were in whaling latitudes it is probable that, with the exception of our consort, there was no vessel within 800 miles of us. For seven long months no letter and no news came to us from the southern world. We had left in exciting times. The Afghan campaign had been undertaken, and war seemed imminent with Russia. We returned opposite the mouth of the Baltic without any means of knowing whether some cruiser might not treat us as we had treated the whales. When we met a fishing-boat at the north of Shetland our first inquiry was as to peace or war. Great events had happened during those seven months: the defeat of Maiwand and the famous march of Roberts from Cabul to Candahar. But it was all haze to us; and, to this day, I have never been able to get that particular bit of military history straightened out in my own mind.

The perpetual light, the glare of the white ice, the deep blue of the water, these are the things which one remembers most clearly, and the dry, crisp, exhilarating air, which makes mere life the keenest of pleasures. And then there are the innumerable sea-birds, whose call is for ever ringing in your ears—the gulls, the fulmars, the snow-birds, the burgomasters, the loons, and the rotjes. These fill the air, and below, the waters are for ever giving you a peep of some strange new creature. The commercial whale may not often come your way, but his less valuable brethren abound on every side. The finner shows his 90 feet of worthless tallow, with the absolute conviction that no whaler would condescend to lower a boat for him. The mis-shapen hunchback whale, the ghost-like white whale, the narwhal, with his unicorn horn, the queer-looking bottle-nose, the huge, sluggish, Greenland shark, and the terrible killing grampus, the most formidable of all the monsters of the deep,—these are the creatures who own those unsailed seas. On the ice are the seals, the saddle-backs, the ground seals and the huge bladdernoses, 12 feet from nose to tail, with the power of blowing up a great blood-red football upon their noses when they are angry, which they usually are. Occasionally one sees a white Arctic fox upon the ice, and everywhere are the bears. The floes in the neighbourhood of the sealing-ground are all criss-crossed with their tracks—poor harmless creatures, with the lurch and roll of a deep-sea mariner. It is for the sake of the seals that they come out over those hundreds of miles of ice; and they have a very ingenious method of catching them, for they will choose a big icefield with just one blow-hole for seals in the middle of it. Here the bear will squat, with its powerful forearms crooked round the hole. Then, when the seal’s head pops up, the great paws snap together, and Bruin has got his luncheon. We used occasionally to burn some of the cook’s refuse in the engine-room fires, and the smell would, in a few hours, bring up every bear for many miles to leeward of us.

Though twenty or thirty whales have been taken in a single year in the Greenland seas, it is probable that the great slaughter of last century has diminished their number until there are not more than a few hundreds in existence. I mean, of course, of the right whale, for the others, as I have said, abound. It is difficult to compute the numbers of a species which comes and goes over great tracts of water and among huge icefields, but the fact that the same whale is often pursued by the same whaler upon successive trips shows how limited their number must be. There was one, I remember, which was conspicuous through having a huge wart, the size and shape of a beehive, upon one of the flukes of its tail. “I’ve been after that fellow three times,” said the captain, as we dropped our boats. “He got away in ’71. In ’74 we had him fast, but the harpoon drew. In ’76 a fog saved him. It’s odds that we have him now!” I fancied that the betting lay rather the other way myself, and so it proved, for that warty tail is still thrashing the Arctic seas for all that I know to the contrary.

I shall never forget my own first sight of a right whale. It had been seen by the look-out on the other side of a small icefield, but had sunk as we all rushed on deck. For ten minutes we awaited its reappearance, and I had taken my eyes from the place, when a general gasp of astonishment made me glance up, and there was the whale in the air. Its tail was curved just as a trout’s is in jumping, and every bit of its glistening lead-coloured body was clear of the water. It was little wonder that I should be astonished, for the captain, after thirty voyages, had never seen such a sight. On catching it we discovered that it was very thickly covered with a red, crab-like parasite, about the size of a shilling, and we conjectured that it was the irritation of these creatures which had driven it wild. If a man had short, nailless flippers, and a prosperous family of fleas upon his back, he would appreciate the situation.

Apart from sport, there is a glamour about those circumpolar regions which must affect everyone who has penetrated to them. My heart goes out to that old, grey-headed whaling captain who, having been left for an instant when at death’s door, staggered off in his night gear, and was found by nurses far from his house and still, as he mumbled, “pushing to the norrard.” So an Arctic fox, which a friend of mine endeavoured to tame, escaped, and was caught many months afterwards in a gamekeeper’s trap in Caithness. It was also pushing norrard, though who can say by what strange compass it took its bearings? It is a region of purity, of white ice and of blue water, with no human dwelling within a thousand miles to sully the freshness of the breeze which blows across the icefields. And then it is a region of romance also. You stand on the very brink of the unknown, and every duck that you shoot bears pebbles in its gizzard which come from a land which the maps know not. It was a strange and fascinating chapter of my life.

I went on board the whaler a big, straggling youth, I came off it a powerful, well-grown man. I have no doubt that my physical health during my whole life has been affected by that splendid air, and that the inexhaustible store of energy which I have enjoyed is to some extent drawn from the same source. It was mental and spiritual stagnation, or even worse, for there is a coarsening effect in so circumscribed a life with comrades who were fine, brave fellows, but naturally rough and wild. However I had my health to show for it, and also more money than I had ever possessed before. I was still boyish in many ways, and I remember that I concealed gold pieces in every pocket of every garment, that my mother might have the excitement of hunting for them. It added some fifty pounds to her small exchequer.

Now I had a straight run in to my final examination, which I passed with fair but not notable distinction at the end of the winter session of 1881. I was now a Bachelor of Medicine and a Master of Surgery, fairly launched upon my professional career.