CHAPTER IX

I RETURN TO THE STAGE

I was still on friendly terms with an actor from the Porte Saint Martin Theater, who had been appointed stage manager there. Marc Fournier was at that time manager of this theater. A piece entitled “La Biche au Bois” was then being played. It was a fairyland story, and was having great success. A delicious actress from the Odéon Theater, Mlle. Debay, had been engaged for the principal rôle. She played tragedy princesses most charmingly. I often had tickets for the Porte Saint Martin, and I thoroughly enjoyed “La Biche au Bois.” Mme. Ulgade sang admirably in her rôle of the young prince, and amazed me. Then, too, Marquita charmed me with her dancing. She was delightful in her dances, which were so animated, so characteristic, and always so full of distinction. Thanks to old Josse I knew everyone; but to my surprise and terror, one evening, toward five o’clock, on arriving at the theater to take our seats, he exclaimed on seeing me:

“Why, here is our princess, our little “Biche au Bois.” Here she is! It is the Providence that watches over theaters who has sent her!”

I struggled like an eel caught in a net, but it was all in vain. M. Marc Fournier, who could be very charming, gave me to understand that I should be doing him a veritable service and keeping up the receipts. Josse, who guessed what my scruples were, exclaimed:

“But, my dear child, it will still be your high art, for it is Mlle. Debay from the Odéon Theater who is playing this rôle of Princess, and Mlle. Debay is the first artiste at the Odéon, and the Odéon is an imperial theater, so that it cannot be any disgrace after your studies.”

Marquita, who had just arrived, also persuaded me, and Mme. Ulgade was sent for to rehearse the duos I was to sing. Yes, and I was to sing with a veritable artiste, one who was considered to be the first artiste of the Opéra Comique.

The time passed by, and Josse helped me to rehearse my rôle, which I almost knew, as I had seen the piece often, and I had an extraordinary memory. The minutes flew, and the half hours made up entire hours. I kept looking at the clock, the large clock in the manager’s room, where I was studying my rôle. Mme. Ulgade rehearsed with me. She thought my voice was pretty, but I kept singing wrong, and she helped and encouraged me all the time.

I was dressed up in Mlle. Debay’s clothes, and finally the moment arrived and the curtain was raised. Poor me! I was more dead than alive, but my courage returned after a triple burst of applause for the couplet which I sang on waking, in very much the same way as I should have murmured a series of Racine’s lines.

When the performance was over Marc Fournier offered me, through Josse, a three years’ engagement; but I asked to be allowed to think it over. Josse had introduced me to a dramatic author, Lambert Thiboust, a charming man who was certainly talented, too. He thought I was just the ideal actress for his heroine, La Bergère d’Ivry, but M. Faille, an old actor who had become the manager of the Ambigu Theater, was not the only person to consult. A certain M. De Chilly had some interest in the theater. He had made his name in the rôle of Rodin in the “Juif Errant,” and, after marrying a rather wealthy wife, had left the stage, and was now interested in the business side of theatrical affairs. He had, I think, just given the Ambigu up to Faille. De Chilly was then helping on a charming girl named Laurence Gérard. She was gentle and very bourgeois, rather pretty, but without any real beauty or grace. Faille told Lambert Thiboust that he had spoken to Laurence Gérard, but that he was ready to do as the author wished in the matter. The only thing he stipulated was that he should hear me before deciding. I was willing to humor the poor fellow, who must have been as poor a manager as he had been an artiste. I acted for him at the Ambigu Theater. The stage was only lighted by the wretched servante, a little transportable lamp. About a yard in front of me I could see M. Faille balancing himself on his chair, one hand on his waistcoat and the fingers of the other hand in his enormous nostrils. This disgusted me horribly. Lambert Thiboust was seated near him, his handsome face smiling, as he looked at me encouragingly.

I was playing in “On ne Badine pas avec l’Amour,” because the play was in prose, and I did not want to take poetry. I believe I was perfectly charming in my rôle, and Lambert Thiboust thought so, too; but when I had finished, poor Faille got up in a clumsy, pretentious way, said something in a low voice to the author, and took me to his own room.

“My child,” remarked the worthy but stupid manager, “you are not at all suitable for the stage!”

I resented this, but he continued:

“Oh, no, not at all.” And, as the door then opened, he added, pointing to the newcomer, “Here is M. De Chilly, who was also listening to you, and he will say just the same as I say.”

M. De Chilly nodded and shrugged his shoulders.

“Lambert Thiboust is mad,” he remarked, “no one ever saw such a thin shepherdess!”

He then rang the bell and told the boy to fetch Mlle. Laurence Gérard. I understood and, without taking leave of the two boors, I left the room.

My heart was heavy, though, as I went back to the foyer, where I had left my hat. I found Laurence Gérard there, but she was fetched away the next moment. I was standing near her and, as I looked in the glass, I was struck by the contrast between us. She was plump, with a wide face, magnificent black eyes, her nose was rather canaille, her mouth heavy, and there was a very ordinary look about her generally. I was fair, slight, and frail-looking, like a reed, with a long, pale face, blue eyes, a rather sad mouth, and a general look of distinction. This hasty vision consoled me for my failure, and then, too, I felt that this Faille was a nonentity, and that De Chilly was common. Five days later Mlle. Debay was well again and took her rôle as usual.

I was destined to meet with both of these men again later on in my life. Chilly, soon after, as manager at the Odéon; and Faille, twenty years later, in such a wretched situation that the tears came to my eyes when he appeared before me and begged me to play for his benefit.

“I beseech you,” said the poor man. “You will be the only attraction at this performance, and I have only you to count on for the receipts.”

I shook hands with him. I do not know whether he remembered our first interview, but I remembered it well, and could only hope that he did not.

Before I would accept the engagement at the Porte Saint Martin, I wrote to Camille Doucet. The following day I received a letter asking me to go to the offices of the Ministry. It was not without some emotion that I went to see this kind man. He was standing up waiting for me when I was ushered into the room. He held out his hands to me and drew me gently toward him.

“Oh, what a terrible child!” he said, giving me a chair. “Come now, you must be calmer. It will never do to waste all these admirable gifts in voyages, escapades, and boxing people’s ears!”

I was deeply moved by his kindness, and my eyes were full of regret as I looked at him.

“Now, don’t cry, my dear child, don’t cry. Let us try and find out how we are to make up for all this folly.”

He was quiet for a moment, and then, opening a drawer, he took out a letter.

“Here is something which will perhaps save us,” he said.

It was a letter from Duquesnel, who had just been appointed manager at the Odéon Theater, together with Chilly.

“I am asked for some young artistes to make up the Odéon company. Well, we must attend to this.” He got up, and accompanying me to the door, said, as I went away: “We shall succeed.”

I went back home, and began at once to rehearse all my rôles in Racine’s plays. I waited very anxiously for several days, consoled by Mme. Guérard, who succeeded in restoring my confidence. Finally, I received a letter, and went at once to the Ministry. Camille Doucet received me with a beaming expression on his face.

“It’s settled,” he said. “Oh, but it has not been easy, though,” he added. “You are very young, but very celebrated already for your headstrong character. The only thing is, I have pledged my word that you will be as gentle as a young lamb.”

“Yes, I will be gentle, I promise,” I replied, “if only out of gratitude. But what am I to do?”

“Here is a letter for Félix Duquesnel,” he replied; “he is expecting you.”

I thanked Camille Doucet heartily, and he then said:

“I shall see you again less officially at your aunt’s on Thursday. I have had an invitation this morning to dine there, so you can tell me then what Duquesnel says.”

It was then half past ten in the morning. I went home to put some pretty clothes on. I chose an underskirt of canary yellow, a dress of black silk with the skirt scalloped round, and a straw hat trimmed with corn and black ribbon. It must have been delightfully mad looking. Arrayed in this style, feeling very joyful and full of confidence, I went to call on Félix Duquesnel. I waited a few moments in a little room very artistically furnished. A young man appeared, looking very elegant. He was smiling and altogether charming. I could not grasp the fact that this fair-haired, gay young man would be my manager.

After a short conversation we agreed on every point we touched.

“Come to the Odéon at two o’clock,” said Duquesnel, by way of leavetaking, “and I will introduce you to my partner. I ought to say it the other way round, according to society etiquette,” he added, laughing, “but we are talking theater.”

He came a few steps down the staircase with me and stayed there leaning over the balustrade to wish me good-by.

At two o’clock precisely I was at the Odéon, and had to wait an hour. I began to grind my teeth, and only the remembrance of my promise to Camille Doucet prevented me from departing.

Finally, Duquesnel appeared and took me across to the manager’s office.

“You will now see the other ogre,” he said, and I pictured to myself the other ogre as charming as his partner. I was therefore greatly disappointed on seeing a very ugly little man whom I recognized as Chilly.

He eyed me up and down most impolitely, and pretended not to recognize me. He signed to me to sit down and, without a word, handed me a pen and showed me where to sign my name on the paper before me.

Mme. Guérard interposed, laying her hand on mine.

“Do not sign without reading it,” she said.

“Are you mademoiselle’s mother?” he asked, looking up.

“No,” she said, “but it is just the same as though I were.”

“Well, yes, you are right. Read it quickly,” he continued, “and then sign or leave it alone, but be quick.”

I felt the color coming into my face, for this man was odious. Duquesnel whispered to me:

“There’s no ceremony about him, but he’s all right, don’t take offense.”

I signed my engagement and handed it to his ugly partner.

“You know,” he remarked, “M. Duquesnel is responsible for you. I should not upon any account have engaged you.”

“And if you had been alone, monsieur,” I answered, “I should not have signed; so we are quits.”

I went away at once and hurried to my mother’s to tell her, for I knew this would be a great joy for her. Then, that very day, I set off with my petite dame to buy everything necessary for furnishing my dressing-room. The following day I went to the convent in the Rue Notre Dame des Champs to see my dear governess, Mlle. De Brabender. She had been ill, with acute rheumatism in all her limbs, for the last thirteen months. She had suffered so much that she looked like a different person. She was lying in her little white bed, a little white cap covering her hair, her big nose was drawn with pain, her washed-out eyes seemed to have no color in them. Her formidable mustache alone bristled up with constant spasms of pain. Besides all this she was so strangely altered that I wondered what had caused the change. I went nearer and, bending down, kissed her gently. I then gazed at her so inquisitively that she understood instinctively. With her eyes she signed to me to look on the table near her, and there in a glass I saw all my dear old friend’s teeth. I put the three roses I had brought her in the glass and, kissing her again, I asked her forgiveness for my impertinent curiosity. I left the convent with a very heavy heart, for the Mother Superior took me in the garden and told me that my beloved Mlle. De Brabender could not live much longer. I therefore went every day for a time to see my gentle old governess, but as soon as the rehearsals commenced at the Odéon my visits had to be less frequent.

One morning about seven o’clock, a message came from the convent to fetch me in great haste, and I was present at the dear woman’s death agony. Her face lighted up at the supreme moment with such a holy look that I suddenly longed to die. I kissed her hands which were holding the crucifix: they had already turned cold. I asked to be allowed to be there when she was placed in her coffin.

On arriving at the convent the next day, at the hour fixed, I found the Sisters in such a state of consternation that I was alarmed. What could have happened, I wondered? They pointed to the door of the cell without uttering a word. The nuns were standing round the bed, on which was the most extraordinary-looking being imaginable. My poor governess, lying rigid on her deathbed, had a man’s face. Her mustache had grown longer, and she had a beard of half an inch all round her chin. Her mustache and beard were sandy, while the long hair framing her face was white. Her mouth, without the support of the teeth, had sunk in so that her nose fell on the sandy mustache. It was like a terrible and ridiculous-looking mask, instead of the sweet face of my friend. It was the face of a man, while the little, delicate hands were those of a woman.

There was an awestruck expression in the eyes of the nuns in spite of the assurance of the nurse, who had declared to them that the body was that of a woman. They had dressed the poor dead body, but the poor little Sisters were trembling and crossing themselves all the time.

The day after this dismal ceremony I made my début at the Odéon in “Le Jeu de l’Amour et du Hasard.” I was not suitable for Marivand’s pieces, as they require a certain coquettishness and an affectation which were not then among my qualities. Then, too, I was rather too slight, so that I had no success at all. Chilly happened to be passing along the corridor, just as Duquesnel was talking to me and encouraging me. Chilly pointed to me and remarked:

“They are no good, these grand folks, there is not even any pluck about them.”

I was furious at the man’s insolence, and the blood rushed to my face, but I saw through my half-closed eyes Camille Doucet’s face, that face always so clean shaven and young looking, under his crown of white hair. I thought it was a vision of my mind, which was always on the alert, on account of the promise I had made. But no, it was he himself, and he came up to me.

“What a pretty voice you have,” he said. “Your second appearance will be such a pleasure to us!”

This man was always courteous, but truthful. This début of mine had not given him any pleasure, but he was counting on my next appearance, and he had spoken the truth. I had a pretty voice, and that was all that anyone could say.

I remained at the Odéon and worked very hard. I was always ready to take anyone’s place at a moment’s notice, for I knew all the rôles. I had some success, and the students approved of me. When I came on the stage I was always greeted by applause from them. A few old sticklers looked down at the pit to command silence, but no one cared a straw for them.

Finally, my day of triumph dawned. Duquesnel had the happy idea of putting “Athalie” on again with Mendelssohn’s choruses. Beauvallet, who had been odious as a professor, was charming as a comrade. By special permission from the Ministry he was to play Joad. The rôle of Zacharie was assigned to me. Some of the Conservatoire pupils were to take the spoken choruses, and the pupils who studied singing undertook the musical part. The rehearsals were so bad that Duquesnel and Chilly were in despair. Beauvallet, who was more agreeable now, but not choice as regarded his language, muttered some terrible words. We began over and over again, but it was all to no purpose. The spoken choruses were simply abominable. Chilly exclaimed at last:

“Well, let the young one say all the spoken choruses. That would be right enough with her pretty voice!”

Duquesnel did not utter a word, but he pulled his mustache to hide a smile. Chilly was coming round to his protégée after all. He nodded his head in an indifferent way in answer to his partner’s questioning look, and we began again, I reading all the spoken choruses. Everyone applauded, and the conductor of the orchestra was delighted, for the poor man had suffered enough. The first performance was a veritable small triumph for me! Oh! quite a small one, but still full of promise for my future. The public, charmed with the sweetness of my voice and its crystal purity, encored the part of the spoken choruses, and I was rewarded by three bursts of applause.

At the end of the act Chilly came to me and said:

“You were adorable!” He addressed me familiarly, using the French thou, and this rather annoyed me; but I answered mischievously, using the same form of speech:

“You think I am not so thin now?”

He burst into a fit of laughter, and from that day forth we both used the familiar thou and became the best friends imaginable.

Oh, that Odéon Theater! It is the theater I have loved most. I was very sorry to leave it, for everyone liked each other there, and everyone was gay. The theater was a little like the continuation of school. The young artistes came there, and Duquesnel was an intelligent manager, and very polite and young himself. During the rehearsal we often went off, several of us together, to play at hide and seek in the Luxembourg, during the scenes in which we were not acting. I used to think of my few months at the Comédie Française. The little world I had known there had been stiff, scandal-mongering, and jealous. I recalled my few months at the Gymnase. Hats and dresses were always discussed there, and everyone chattered about a hundred things that had nothing to do with art.

At the Odéon I was very happy. We thought of nothing but putting on plays, and we rehearsed morning, afternoon, and at all hours, and I liked that very much.

For the summer I had taken a little house in the Villa Montmorency at Auteuil. I went to the theater in a “little duke,” which I drove myself. I had two wonderful ponies that Aunt Rosine had given to me, because they had very nearly broken her neck by taking fright at St. Cloud at a whirligig of wooden horses. I used to drive at full speed along the quays, and in spite of the atmosphere brilliant with the July sunshine and the gayety of everything outside, I always ran up the cold, cracked steps of the theater with veritable joy, and rushed up to my dressing-room, wishing everyone I passed “Good morning” on my way. When I had taken off my coat and gloves I went on the stage, delighted to be once more in that infinite darkness with only a poor light, a servante, hanging here and there on a tree, a turret, a wall, or placed on a bench, thrown on the faces of the artistes for a few seconds.

There was nothing more vivifying for me than that atmosphere full of microbes, nothing more gay than that obscurity, and nothing more brilliant than that darkness.

One day my mother had the curiosity to come behind the scenes. I thought she would have died with horror and disgust.

“Oh, you poor child!” she murmured, “How can you live in that?” When once she was outside again she began to breathe freely, taking long gasps several times. Oh! yes, I could live in it, and I could scarcely live except in it. Since then I have changed a little, but I still have a great liking for that gloomy workshop in which we joyous lapidaries of art cut the precious stones supplied to us by the poets.

The days passed by, carrying away with them all our little disappointed hopes, and fresh days dawned bringing fresh dreams, so that life seemed to me eternal happiness. I played in turn in “Le Marquis de Villemer” and “François le Champi.” In the former I took the part of the foolish Baroness, an expert woman of thirty-five years of age. I was scarcely twenty-one myself, and I looked seventeen. In the second piece I played Mariette, and had great success.

Those rehearsals of the “Marquis de Villemer” and “François le Champi” have remained in my memory as so many exquisite hours.

Mme. George Sand was a sweet, charming creature, extremely timid. She did not talk much, but smoked all the time. Her large eyes were always dreamy, and her mouth, which was rather heavy and common, had the kindest expression. She had, perhaps, a medium-sized figure, but she was no longer upright. I used to watch her with the most romantic affection, for had she not been the heroine of a fine love romance!

I used to sit down by her, and when I took her hand in mine I held it as long as possible. Her voice, too, was gentle and fascinating.

Prince Napoleon, commonly known as “Plon-Plon,” often used to come to George Sand’s rehearsals. He was extremely fond of her. The first time I ever saw that man I turned pale, and felt as though my heart had stopped beating. He looked so much like Napoleon I.

Mme. Sand introduced me to him in spite of my wishes. He looked at me in an impertinent way, and I did not like him. I scarcely replied to his compliments, and went closer to George Sand.

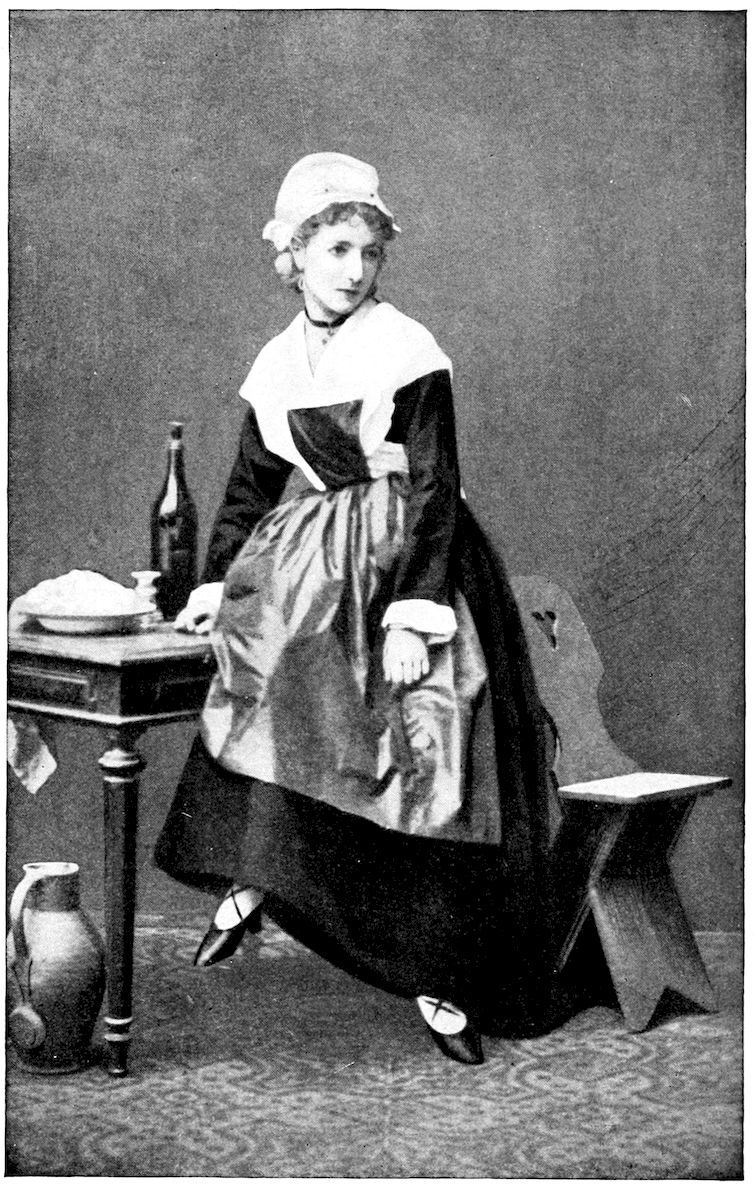

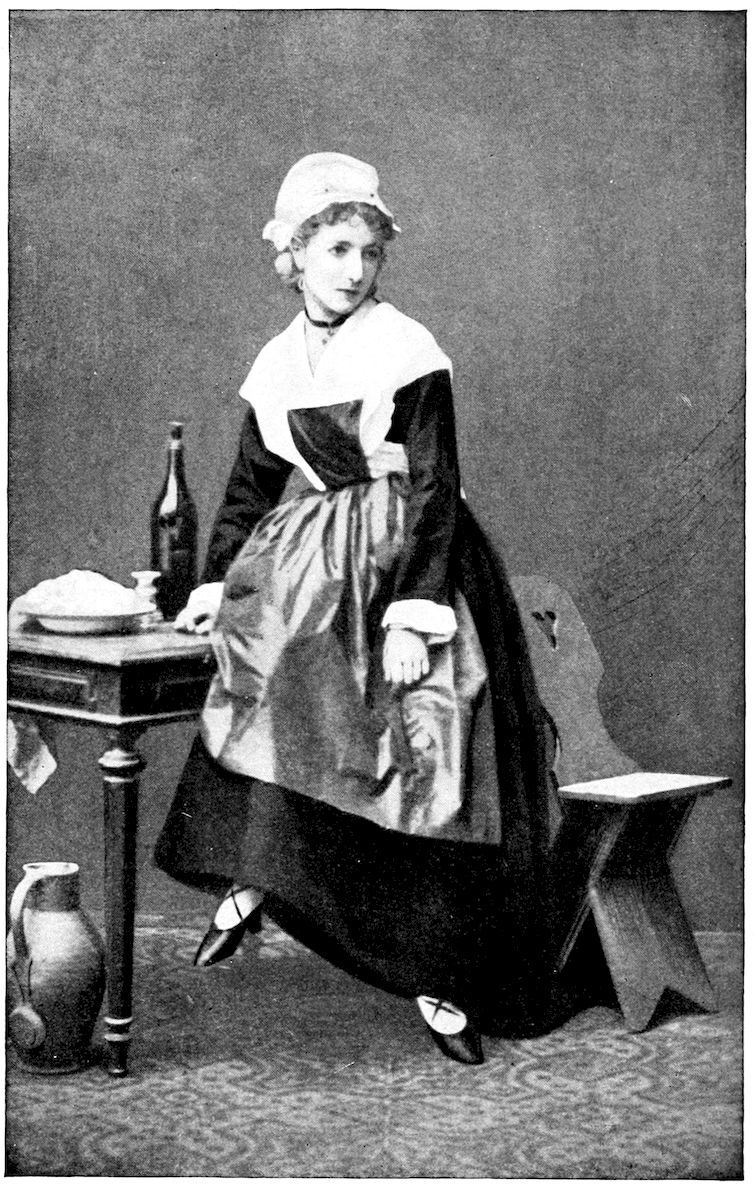

SARAH BERNHARDT IN “FRANÇOIS LE CHAMPI.”

“Why, she is in love with you!” he exclaimed, laughing.

George Sand stroked my cheek gently.

“She is my little Madonna,” she answered, “do not torment her.”

I stayed with her, casting displeased and furtive glances at the prince. Gradually, though, I began to enjoy listening to him, for his conversation was brilliant, serious, and at the same time witty. He sprinkled his discourses and his replies with words that were a trifle crude, but all that he said was interesting and instructive. He was not very indulgent, though, and I have heard him say base, horrible things about little Thiers which I believe had little truth in them. He drew such an amusing portrait one day of that agreeable Louis Bouilhet, that George Sand, who liked him, could not help laughing, although she called the prince a bad man. He was very unceremonious, too, but at the same time he did not like people to be wanting in respect to him. One day an artiste named Paul Deshayes, who was playing in “François le Champi,” came into the artistes’ foyer. Prince Napoleon was there, Mme. George Sand, the curator of the library, whose name I have forgotten, and I. This artiste was common and something of an anarchist. He bowed to Mme. Sand and, addressing the prince, said:

“You are sitting on my gloves, sir.”

The prince scarcely moved, pulled the gloves out and, throwing them on the floor, remarked:

“I thought this seat was clean.”

The actor colored, picked up the gloves, and went away murmuring some revolutionary threat.

I played the part of Hortense in “Le Testament de César Girôdot,” and of Anna Danby in Alexandre Dumas’ “Kean.”

On the evening of the first performance of the latter piece the public was very disagreeable. Dumas’ père was quite out of favor, on account of a private matter that had nothing to do with art. Politics, for some time past, had been exciting everyone, and the return of Victor Hugo from exile was very much desired. When Dumas entered his box, he was greeted by yells. The students were there in full force, and they began shouting for Ruy Blas. Dumas rose and asked to be allowed to speak. “My young friends ...” he began, as soon as there was silence. “We are quite willing to listen,” called out some one, “but you must be alone in your box.”

Dumas protested vehemently. Several members of the orchestra took his side, for he had invited a woman into his box, and whoever that woman might be, no one had any right to insult her in so outrageous a manner. I had never yet witnessed a scene of this kind. I looked through the hole in the curtain, and was very much interested and excited. I saw our great Dumas, pale with anger, clenching his fists, shouting, swearing, and storming. Then suddenly there was a burst of applause. The woman had disappeared from the box. She had taken advantage of the moment when Dumas, leaning well over the front of the box, was answering:

“No, no, this woman shall not leave the box!”

Just at this moment she slipped away, and the whole house, delighted, shouted: “Bravo!” Dumas was then allowed to continue, but only for a few seconds. Cries of “Ruy Blas! Ruy Blas! Victor Hugo! Hugo!” could then be heard again in the midst of an uproar truly infernal. We had been ready to commence the play for an hour, and I was greatly excited. Chilly and Duquesnel then came to us on the stage.

“Courage, mes enfants, for the house has gone mad,” they said. “We will commence, anyhow, let what will happen!”

“I’m afraid I shall faint,” I said to Duquesnel. My hands were as cold as ice and my heart was beating wildly. “What am I to do,” I asked him, “if I get too frightened?”

“There’s nothing to be done,” he replied. “Be frightened, but go on playing, and don’t faint upon any account!”

The curtain was drawn up in the midst of a veritable tempest, bird cries, mewing of cats, and a heavy rhythmical refrain of “Ruy Blas! Ruy Blas! Victor Hugo! Victor Hugo!”

My turn came. Berton père, who was playing Kean, had been received badly. I was wearing the eccentric costume of an Englishwoman in the year 1820. As soon as I appeared I heard a burst of laughter, and I stood still, rooted to the spot in the doorway. But the very same instant the cheers of my dear friends, the students, drowned the laughter of the disagreeable people. I took courage, and even felt a desire to fight. But it was not necessary, for after the second, endlessly long, harangue, in which I give an idea of my love for Kean, the house was delighted, and gave me an ovation. Ignotus wrote the following paragraph in the Figaro:

“Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt appeared wearing an eccentric costume, which increased the tumult, but her rich voice—that astonishing voice of hers—appealed to the public, and she charmed them like a little Orpheus.”

After “Kean” I played in “La Loterie du Mariage.” When we were rehearsing the piece, Agar came up to me one day, in the corner where I usually sat. I had a little armchair there from my dressing-room, and put my feet up on a straw chair. I liked this place, because there was a little gas burner there, and I could work while waiting for my turn to go on the stage. I loved embroidering and tapestry work. I had a quantity of different kinds of fancy work commenced, and could take up one or the other as I felt inclined.

Mlle. Agar was an admirable creature. She had evidently been created for the joy of the eyes. She was a brunette, tall, pale, with large, dark, gentle eyes, a very small mouth with full rounded lips, which went up at the corners in an almost imperceptible smile. She had exquisite teeth, and her head was covered with thick, glossy hair. She was the living incarnation of one of the most beautiful types of ancient Greece. Her pretty hands were long and rather soft, while her slow and rather heavy walk completed the evocation. She was the great tragedian of the Odéon Theater. She approached me with her measured tread, followed by a young man of from twenty-four to twenty-six years of age.

“Well, my dear,” she said, kissing me, “there is a chance for you to make a poet happy.” She then introduced François Coppée. I invited the young man to sit down, and then I looked at him more thoroughly. His handsome face, emaciated and pale, was that of the immortal Bonaparte. A thrill of emotion went through me, for I adored Napoleon I.

“Are you a poet, monsieur?” I asked.

“Yes, mademoiselle.”

His voice, too, trembled, for he was still more timid than I was.

“I have written a little piece,” he continued, “and Mlle. Agar is sure that you will play it with her.”

“Yes, my dear,” put in Agar, “you are going to play it for him. It is a little masterpiece, and I am sure you will have a gigantic success!”

“Oh, and you, too! You will be so beautiful in it!” said the poet, gazing rapturously at Agar.

I was called on to the stage just at this moment, and on returning a few minutes later I found the young poet talking in a low voice to the beautiful tragedian. I coughed, and Agar, who had taken my armchair, wanted to give it back. On my refusing it she pulled me down on her lap. The young man drew up his chair and we chatted away together, our three heads almost touching. It was decided that after reading the piece I should show it to