CHAPTER XI

I ESTABLISH MY WAR HOSPITAL

For some days I was perfectly dazed, missing the usual life around me, and missing the affection of those I loved. The defense, however, was being organized, and I decided to use my strength and intelligence in tending the wounded. The question was where could we install an ambulance?

The Odéon Theater had closed its doors, but I moved heaven and earth to get permission to organize an ambulance at the Odéon, and, thanks to Emile de Girardin and Duquesnel, my wish was granted. I went to the War Office and made my declaration, and my request and my offers were accepted for a military ambulance.

The next difficulty was that I wanted food. I wrote a line to the Prefect of Police. A military courier arrived very soon after my letter, bringing me a note from the prefect, containing the following lines:

MADAME: If you could possibly come at once I would wait for you until six o’clock. Excuse the earliness of the hour, but I have to be at the Chamber at nine in the morning, and as your note seems to be urgent, I am anxious to do all I can to be of service to you.

COMTE DE KÉRATRY.

I remembered a Comte de Kératry who had been introduced to me at my aunt’s house the evening I had recited poetry accompanied by Rossini. He was a young lieutenant, good-looking, witty, and lively. He had introduced me to his mother, a very charming woman, and I had recited poetry at her soirées. The young lieutenant had gone to Mexico and for some time we had kept up a correspondence, but this had gradually ceased, and we had not met again. I asked Mme. Guérard whether she thought that the prefect might be a near relative of my young friend’s. “It may be so,” she replied, and we discussed this in the carriage which was taking us at once to the Tuileries Palace, where the prefect had his offices. My heart was very heavy when we came to the stone steps. Only a few months previously, one April morning, I had been there with Mme. Guérard. Then, as now, a footman had come forward to open the door of my carriage, but the April sunshine had then lighted up the steps, caught the shining lamps of the state carriages, and sent its rays in all directions. There had been a busy, joyful coming and going of the officers, and elegant salutes had been exchanged. On this occasion the misty, crafty-looking November sun fell heavily on all it touched. Black, dirty-looking cabs drove up one after the other, knocking against the iron gate, grazing the steps, advancing or moving back, according to the coarse shouts of their drivers. Instead of the elegant salutations, I heard now such phrases as:

“Well, how are you, old chap?” “Oh, the wooden jaws!” “Well, any news?” “Yes, it’s the very deuce with us!” etc., etc.... The palace was no longer the same. The very atmosphere had changed. The faint perfume which elegant women leave in the air as they pass was no longer there. A vague odor of tobacco, of greasy clothes, of hair plastered with pomatum made the atmosphere seem heavy. Ah, the beautiful French Empress! I could see her again in her blue dress embroidered with silver, calling to her aid Cinderella’s good fairy to help her on again with her little slipper. The delightful young Prince Imperial, too; I could see him helping me to place the pots of verbena and Marguerites, and holding in his arms, which were not strong enough for it, a huge pot of rhododendrons, behind which his handsome face completely disappeared. I could see the Emperor Napoleon III himself, with his half-closed eyes, clapping his hands at the rehearsal of the courtesies intended for him.

The fair Empress, dressed in strange clothes, had rushed away in the carriage of her American dentist, for it was not even a Frenchman, but a foreigner, who had had the courage to protect the unfortunate woman. And the gentle Utopian Emperor had tried in vain to be killed on the battlefield. Two horses had been killed under him, but he had not received so much as a scratch. And after this he had given up his sword. And we, at home, had all wept with anger, shame, and grief at this giving up of the sword. Yet what courage it must have required for this brave man to carry out such an act! He had wanted to save a hundred thousand men, to spare a hundred thousand lives, and to reassure a hundred thousand mothers. Our poor, beloved Emperor! History will some day do him justice, for he was good, humane, and confiding. Alas! alas! he was too confiding!

I stopped a minute before entering the prefect’s suite of rooms. I was obliged to wipe my eyes, and, in order to change the current of my thoughts, I said to my petite dame:

“Tell me, should you think me pretty if you saw me now for the first time?”

“Oh, yes!” she replied warmly.

“So much the better!” I said, “for I want this old prefect to think me pretty. There are so many things I must ask him for.”

On entering his room, what was my surprise to recognize in him the lieutenant I knew. He had become captain and then prefect of the Seine. When my name was announced by the usher, he sprang up from his chair and came forward with his face beaming and both hands stretched out.

“Ah, you had forgotten me!” he said; and then he turned to greet Mme. Guérard in a friendly way.

“But I never thought I was coming to see you,” I replied; “and I am delighted,” I continued, “for you will let me have everything I ask for.”

“Only that!” he remarked, with a short burst of laughter. “Well, will you give your orders, madame?” he continued.

“Yes, I want bread, milk, meat, vegetables, sugar, wine, brandy, potatoes, eggs, coffee,” I said in one breath.

“Oh, let me get my breath!” exclaimed the count-prefect. “You speak so quickly that I am gasping.”

I was quiet a moment, and then I continued:

“I have started an ambulance at the Odéon, but as it is a military ambulance, the municipal authorities refuse me food. I have five wounded men already, and I can manage for them, but other wounded men are being sent to me, and I shall have to give them food.”

“You shall be supplied above and beyond all your wishes,” said the prefect. “There is food in the palace which was being stored by the unfortunate Empress. She had prepared enough for months and months. I will have all you want sent to you, except meat, bread, and milk, and as regards these I will give orders that your ambulance shall be included in the municipal service, although it is a military one. Then I will give you an order for salt and some other things, which you will be able to get from the Opera.”

“From the Opera!” I repeated, looking at him incredulously. “But it is only being built, and there is nothing but scaffolding there yet.”

“Yes; but you must go through the little doorway under the scaffolding opposite the Rue Scribe; you then go up the little spiral staircase leading to the provision office, and there you will be supplied with what you want.”

“There is still something else I want to ask,” I said.

“Go on, I am quite resigned, and ready for your orders,” he replied.

“Well, I am very uneasy,” I said, “for they have put a stock of powder in the cellars under the Odéon. If Paris were to be bombarded and a shell should fall on the building, we should all be blown up, and that is not the aim and object of an ambulance.”

“You are quite right,” said the kind man, “and nothing could be more stupid than to store powder there. I shall have more difficulty about that, though,” he continued, “for I shall have to deal with a crowd of stubborn bourgeois, who want to organize the defense in their own way. You must try to get a petition for me, signed by the most influential householders and tradespeople in the neighborhood. Now are you satisfied?” he asked.

“Yes,” I replied, shaking hands with him cordially with both hands. “You have been most kind and charming. Thank you very much.”

I then moved toward the door, but I stood still again suddenly, as though hypnotized by an overcoat hanging over a chair. Mme. Guérard saw what had attracted my attention, and she pulled my sleeve gently:

“My dear Sarah,” she whispered, “do not do that.”

I looked beseechingly at the young prefect, but he did not understand.

“What can I do now to oblige you, beautiful Madonna?” he asked.

I pointed to the coat and tried to look as charming as possible.

“I am very sorry,” he said, bewildered, “but I do not understand at all.”

I was still pointing to the coat.

“Give it me, will you?” I said.

“My overcoat?”

“Yes.”

“What do you want it for?”

“For my wounded men when they are convalescent.”

He sank down on a chair in a fit of laughter. I was rather vexed at this uncontrollable outburst, and I continued my explanation.

“There is nothing so funny about it,” I said. “I have a poor fellow, for instance, whose two fingers have been taken off. He does not need to stay in bed for that, naturally, and his soldier’s cape is not warm enough. It is very difficult to warm the big foyer of the Odéon sufficiently, and those who are well enough have to be there. The man I tell you about is warm enough at present, because I took Henri Fould’s overcoat, when he came to see me the other day. My poor soldier is huge, and as Henri Fould is a giant I might never have had such an opportunity again. I shall want a great many overcoats, though, and this looks like a very warm one.”

I stroked the furry lining of the coveted garment, and the young prefect, still choking with laughter, began to empty the pockets of his overcoat. He pulled out a magnificent white silk muffler from the largest pocket.

“Will you allow me to keep my muffler?” he asked.

I put on a resigned expression and nodded my consent. Our host then rang, and when the usher appeared he handed him the overcoat, and said in a solemn voice, in spite of the laughter in his eyes:

“Will you carry this to the carriage for these ladies?”

I thanked him again and went away feeling very happy.

Twelve days later I returned, taking with me a letter covered with the signatures of the householders and tradesmen living near the Odéon.

On entering the prefect’s room I was petrified to see him, instead of advancing to meet me, rush toward a cupboard, open the door, and fling something hastily into it. After this he leaned back against the door as though to prevent my opening it.

“Excuse me,” he said, in a witty, mocking tone, “but I took a violent cold after your first visit. I have just put my overcoat—oh, only an ugly, old overcoat, not a warm one,” he added quickly, “but still an overcoat, inside there, and there it is now, and I will take the key out of the lock.”

He put the key carefully into his pocket, and then came forward and found me a chair. Our conversation soon took a more serious turn, though, for the news was very bad. For the last twelve days the ambulances had been crowded with the wounded. Everything was in a bad way, home politics as well as foreign politics. The Germans were advancing on Paris. The Army of the Loire was being formed. Gambetta, Chanzy, Bourbaki, and Trochn were organizing a desperate defense. We talked for some time about all these sad things, and I told him about the painful impression I had had on my last visit to the Tuileries, of my remembrance of everyone, so brilliant, so considerate, and so happy formerly, and so deeply to be pitied at present. We were silent for a moment, and then I shook hands with him, told him I had received all he had sent, and returned to my ambulance.

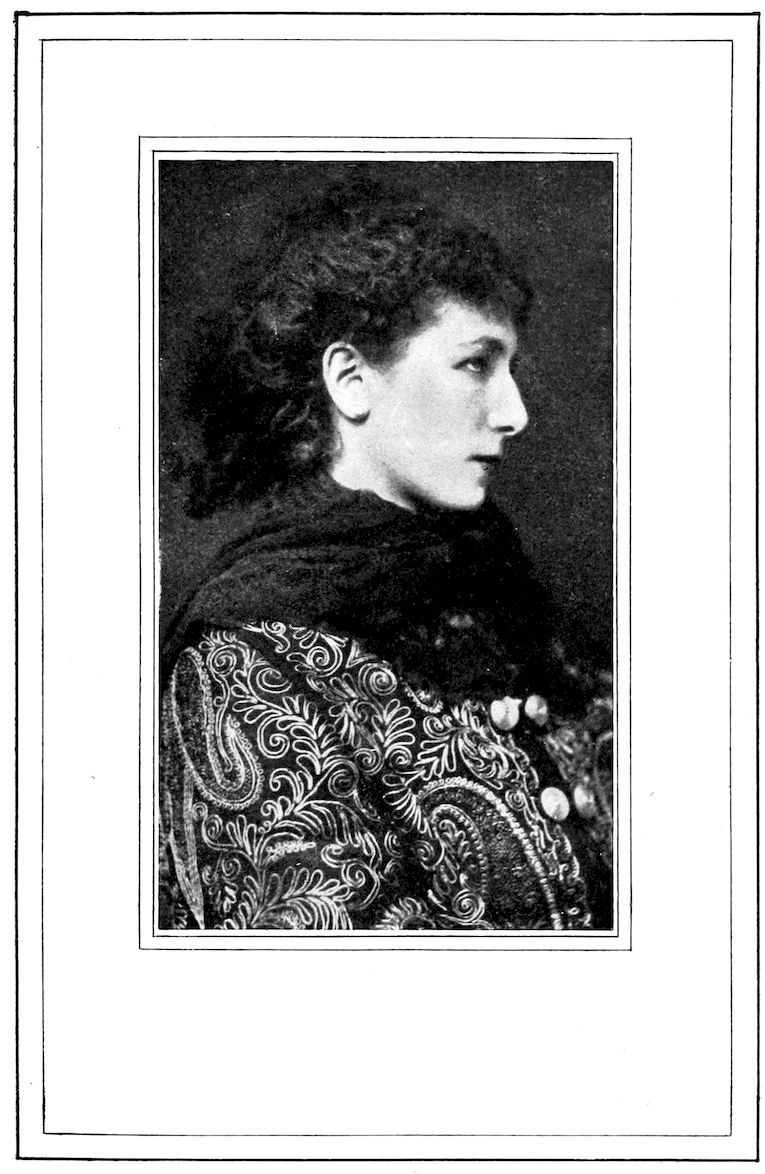

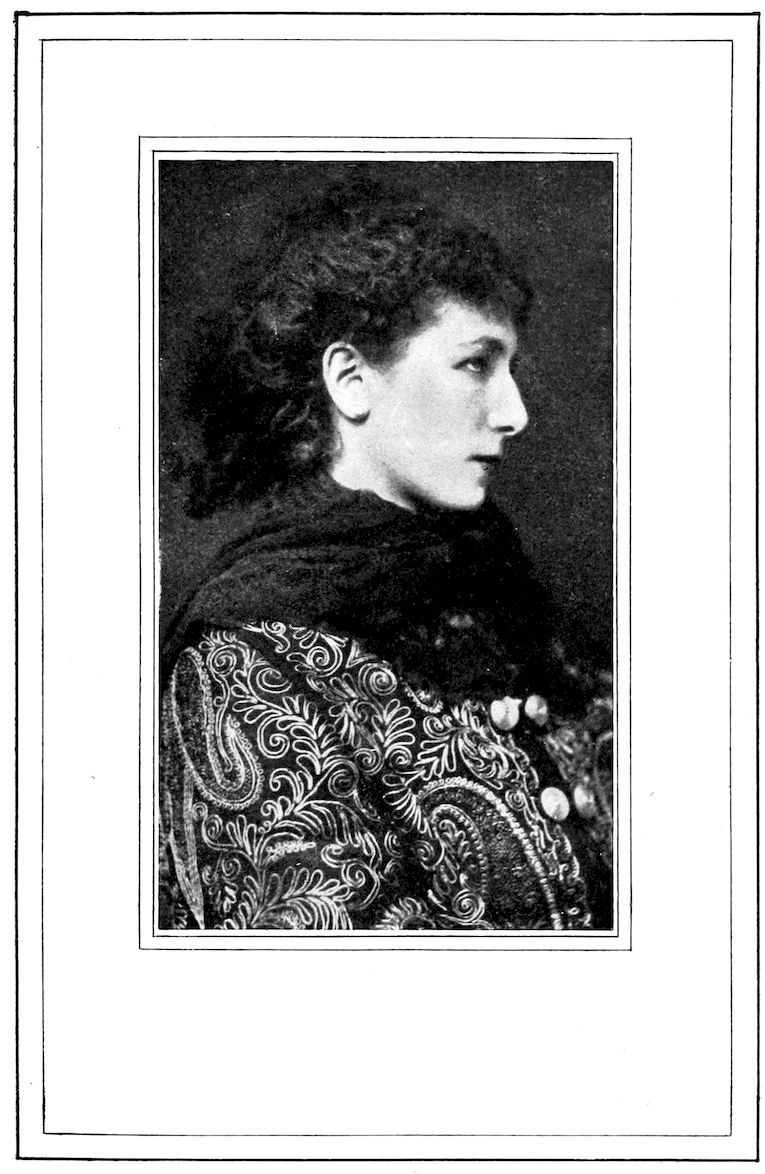

AN EARLY PORTRAIT OF SARAH BERNHARDT.

The prefect had sent me ten barrels of wine and two of brandy; 30,000 eggs all packed in boxes with lime and bran; a hundred bags of coffee, boxes of tea, forty boxes of Albert biscuits, a thousand tins of preserve, and a quantity of other things. M. Menier, the great chocolate manufacturer, had sent me five hundred pounds of chocolate. One of my friends, who was a flour dealer, had made me a present of twenty sacks of flour, ten of which were maize flour. Félix Potin, my neighbor when I was living at 11 Boulevard Malesherbes, had responded to my appeal by sending two barrels of raisins, a hundred boxes of sardines, three sacks of rice, two sacks of lentils, and twenty sugar loaves. From M. De Rothschild I had received two barrels of brandy and a hundred bottles of his own wine for the convalescents. I also received a very unexpected present. Léonie Dubourg, an old schoolfellow of mine at the Grandchamps Convent, sent me fifty tin boxes, each containing four pounds of salt butter. She had married a very wealthy gentleman farmer, who cultivated his own farms, which it seems were very numerous. I was very much touched at her remembering me, for I had never seen her since the old days at the convent. I had also asked for all the overcoats and slippers of my various friends, and I had bought up a job lot of two hundred flannel vests. My Aunt Betty, my blind grandmother’s sister, who is still living in Holland, and is now ninety-three years of age, managed to get for me, through the delightful Dutch Ambassador, Baron ——, three hundred night shirts of magnificent Dutch linen, and a hundred pairs of sheets. I received lint and bandages from every corner of Paris, but it was more particularly from the Palais de l’Industrie that I used to get my provisions of lint and linen for binding wounds. There was an adorable woman there, named Mlle. Hocquigny, who was at the head of all the ambulances. All that she did was done with a cheerful gracefulness, and all that she was obliged to refuse she refused sorrowfully, but still in a gracious manner. She was at that time more than thirty years of age, and although unmarried she looked more like a young married woman. She had large, blue, dreamy eyes, and a laughing mouth, a deliciously oval face, little dimples, and crowning all this grace, this dreamy expression and this coquettish, inviting mouth, a wide forehead like that of the virgins painted by the early painters, a wide and rather prominent forehead, encircled by hair worn in smooth, wide, flat bandeaux, separated by a faultless parting. The forehead seemed like the protecting rampart of this delicious face. Mlle. Hocquigny was adored by everyone, and made much of, but she remained invulnerable to all homage. She was happy in being beloved, but she would not allow anyone to express affection for her.

At the Palais de l’Industrie a remarkable number of celebrated doctors and surgeons were on duty, and they, as well as the convalescents, were all more or less in love with Mlle. Hocquigny. As she and I were great friends, she confided to me her observations and her sorrowful disdain. Thanks to her I was never short of linen nor of lint. I had organized my ambulance with a very small staff. My cook was installed in the public foyer. I had bought her an immense cooking range, so that she could make soups and herb tea for fifty men. Her husband was chief attendant. I had given him two assistants, and Mme. Guérard, Mme. Lambquin, and I were the nurses. Two of us sat up at night, so that we each went to bed every third night. I preferred this to taking on some woman whom I did not know. Mme. Lambquin belonged to the Odéon, where she used to take the part of the duennas. She was plain and had a common face, but she was very talented. She talked loud and was very plain spoken. She called a spade a spade, and liked frankness and no under meaning to things. At times she was a trifle embarrassing with the crudeness of her words and her remarks, but she was kind, active, alert, and devoted. My various friends who were on service at the fortifications came to me in their free time to do my secretarial work. I had to keep a book, which was shown every day to a sergeant who came from the Val-de-Grâce military hospital, giving all details as to how many men came into our ambulance, how many died, and how many recovered and left. Paris was in a state of siege, and no one could go far outside the walls, and no news from outside could be received. The Germans were not, however, round the gates of the city. Baron Larrey came now and then to see me, and I had, as head surgeon, Dr. Duchesne, who gave up his whole time, night and day, to the care of my poor men during the five months that this truly frightful nightmare lasted.

I cannot recall those terrible days without the deepest emotion. It was no longer the country in danger that kept my nerves strung up, but the sufferings of all her children. There were all those who were away fighting, those who were brought in to us wounded or dying, the noble women of the people, who stood for hours and hours in the queue to get the necessary dole of bread, meat, and milk for their poor little ones at home. Ah, those poor women! I could see them from the theater windows, pressing up close to each other, blue with cold, and stamping their feet on the ground to keep them from freezing, for that winter was the most cruel one we had had for twenty years. Frequently one of these poor, silent heroines was brought in to me, either in a swoon from fatigue, or struck down suddenly with congestion caused by cold. On the 20th of December, three of these unfortunate women were brought into the ambulance. One of them had her feet frozen, and she lost the big toe of her right foot. The second was an enormously stout woman, who was suckling her child, and her poor breasts were harder than wood. She simply howled with pain. The youngest of the three was a girl of sixteen to eighteen years of age. She died of cold, on the trestle on which I had had her placed to send her home. On the 24th of December, there were fifteen degrees of cold. I often sent William, our attendant, out with a little brandy to warm the poor women. Oh, the suffering they must have endured, those heartbroken mothers, those sisters, and fiancées, in their terrible dread! How excusable their rebellion seems during the Commune, and even their bloodthirsty madness!

My ambulance was full. I had sixty beds and was obliged to improvise ten more. The soldiers were installed in the artistes’ foyer and in the general foyer, and the officers in a room which had formerly been used for refreshments.

One day a young Breton named Marie le Gallec was brought in. He had been struck by a bullet in the chest and another in the wrist. Dr. Duchesne bound up his chest firmly and splintered his wrist. He then said to me very simply:

“Let him have everything he likes, he is dying.”

I bent over his bed and said to him:

“Tell me anything that would give you pleasure, Marie le Gallec?”

“Soup,” he answered promptly, in the most comic way.

Mme. Guérard hurried away to the kitchen and soon returned with a bowl of broth and pieces of toast. I placed the bowl on the little wooden shelf with four short legs which was so convenient for the meals of our poor sufferers. The wounded man looked up at me and said:

“Barra!” I did not understand, and he repeated: “Barra!” His poor chest caused him to hiss out the word, and he made the greatest efforts to repeat his emphatic request. I sent immediately to the Marine Office thinking that there would surely be some Breton seamen there, and I explained my difficulty, and my ignorance of the Breton dialect. I was informed that the word “barra” meant bread. I hurried at once to Le Gallec with a large piece of bread. His face lighted up and, taking it from me with his sound hand, he broke it up with his teeth and let the pieces fall in the bowl. He then plunged his spoon into the middle of the broth and filled it up with bread until the spoon could stand upright in it. When it stood up without shaking about, the young soldier smiled. He was just preparing to eat this horrible concoction when the young priest from St. Sulpice, who had my ambulance in charge, arrived. I had sent for him on hearing the doctor’s sad verdict. He laid his hand gently on the young man’s shoulder, thus stopping the movement of his arm. The poor fellow looked up at the priest, who showed him the Holy Cup.

“Oh!” he said simply, and then, placing his coarse handkerchief over the steaming soup, he put his hands together. We had arranged the two screens, which we used for isolating the dead or dying, around his bed. He was left alone with the priest while I went on my rounds to calm the murmurers, or help the believers to raise themselves for the prayer. The young priest soon pushed aside the partition, and I then saw Marie le Gallec, with a beaming face, eating his abominable bread sop. He fell asleep soon afterward, roused up to ask for something to drink, and died immediately, in a slight fit of choking.

Fortunately I did not lose many men out of the three hundred who came into my ambulance, for the death of the unfortunate ones completely upset me. I was very young at that time, only twenty-four years of age, but I could nevertheless see the cowardliness of some of the men, and the heroism of many of the others. A young Savoyard eighteen years old had had his forefinger taken off. Baron Larrey was quite sure that he had shot it off himself with his own gun, but I could not believe that. I noticed, though, that in spite of our nursing and care the wound did not heal. I bound it up in a different way, and the following day I saw that the bandage had been altered. I mentioned this to Mme. Lambquin, who was sitting up that night together with Mme. Guérard.

“Good; I will keep my eye on him; you go to sleep, my child, and count on me.”

The next day when I arrived she told me that she had caught the young man scraping the wound on his finger with his knife. I called him and told him that I should have to report this to the Val-de-Grâce Hospital. He began to weep and vowed to me that he would never do it again, and five days later he was well. I signed the paper authorizing him to leave the ambulance, and he was sent to the army of the defense. I often wondered what became of him.

Another of our patients bewildered us, too. Each time that his wound seemed to be just on the point of healing up, he had a violent attack of dysentery which threw him back. This seemed suspicious to Dr. Duchesne, and he asked me to watch the man. At the end of a considerable time, we were convinced that our wounded man had thought out the most comical scheme. He slept next the wall and therefore had no neighbor on the one side. During the night, he managed to file the brass of his bedstead. He put the filings in a little pot which had been used for ointment of some kind. A few drops of water and some salt mixed with this powdered brass formed a poison, which might have cost its inventor his life. I was furious at this stratagem. I wrote to the Val-de-Grâce, and an ambulance conveyance was sent to take this unpatriotic Frenchman away.

But side by side with these despicable men, what heroism we saw! A young captain was brought in one day. He was a tall fellow, a regular Hercules, with a superb head, and a frank expression. On my book he was described as Captain Menesson. He had been struck by a bullet at the top of the arm, just at the shoulder. With a nurse’s assistance I was trying as gently as possible to take off his cloak, when three bullets fell from the hood which he had pulled over his head, and I counted sixteen bullet holes in the cloak. The young officer had stood upright for three hours, serving as a target himself, while covering the retreat of his men as they fired all the time on the enemy. This had taken place among the Champigny vines. He had been brought in unconscious in a hospital conveyance. He had lost a great deal of blood, and was half dead with fatigue and weakness. He was very gentle and charming, and thought himself sufficiently well two days later to return to the fight. The doctor, however, would not allow this, and his sister, who was a nun, besought him to wait until he was something like well again.

“Oh, not quite well,” she said, smiling; “but just well enough to have strength to fight.”

Soon after he came into the ambulance the Cross of the Legion of Honor was brought for him, and this was a moment of intense emotion for everyone. The unfortunate wounded men who could not move turned their suffering faces toward him and, with their eyes shining through a mist of tears, gave him a fraternal look. The more convalescent among them held out their hands to the young giant.

It was Christmas Eve, and I had decorated the ambulance with festoons of green leaves. I had made pretty little chapels in front of the Virgin Mary, and the young priest from St. Sulpice came to take part in our poor but poetical Christmas service. He repeated some beautiful prayers, and the wounded men, many of whom were from Brittany, sang some sad, solemn songs, full of charm. Porel, the present manager of the Vaudeville Theater, had been wounded on the Avron Plateau. He was then convalescent, and was one of my guests, together with two officers now ready to leave the ambulance. That Christmas supper is one of my most charming and at the same time most melancholy memories. It was served in the small room which we had made into a bedroom. Our three beds were covered with draperies and skins which I had fetched from home, and we used them as seats.

Mlle. Hocquigny had sent me five yards of white pigs’ pudding,[1] the famous Christmas dish, and all my poor soldiers who were well enough, were delighted with this delicacy. One of my friends had had twenty large brioche cakes made for me, and I had ordered some large bowls of punch, the colored flames from which amused the grown-up sick children immensely. The young priest from St. Sulpice accepted a piece of brioche and, after taking a little white wine, left us. Ah, how charming and good he was, that poor young priest! And how well he managed to make that unbearable Fortin cease talking. Gradually the latter began to get humanized, until finally he began to think the priest was a good sort of fellow. Poor young priest! He was shot by the Communists, and I cried for days and days over his murder.