CHAPTER XXII

MY STAY IN ENGLAND

My intense desire to win over the English public had caused me to overtax my strength. I had done my utmost at the first performance and had not spared myself in the least. The consequence was that in the night I vomited blood in such an alarming way that a messenger was despatched to the French Embassy in search of a physician. Dr. Vintras, who was at the head of the French Hospital in London, found me lying on my bed, exhausted and looking more dead than alive. He was afraid that I should not recover and requested that my family be sent for. I made a gesture with my hand to the effect that it was not necessary. As I could not speak, I wrote down with a pencil: “Send for Dr. Parrot.”

Dr. Vintras remained with me part of the night, putting crushed ice between my lips every five minutes. At length toward five in the morning the blood vomiting ceased, and thanks to a potion that the doctor gave me, I fell asleep.

We were to play “L’Etrangère” that night at the Gaiety and, as my rôle was not a very fatiguing one, I wanted to perform my part quand-même.

Dr. Parrot arrived by the four o’clock boat and refused categorically to give his consent. He had attended me from my childhood. I really felt much better, and the feverishness had left me. I wanted to get up, but to this Dr. Parrot objected.

Presently, Dr. Vintras and Mr. Mayer, the impresario of the Comédie Française, were announced. Mr. Hollingshead, the director of the Gaiety Theater, was waiting in a carriage at the door to know whether I was going to play in “L’Etrangère,” the piece announced on the bills. I asked Dr. Parrot to rejoin Dr. Vintras in the drawing-room and I gave instructions for Mr. Mayer to be introduced into my room.

“I feel much better,” I said to him, very quickly. “I’m very weak still, but I will play. Ssh! ... don’t say a word here. Tell Hollingshead and wait for me in the smoking room, but don’t let anyone else know.”

I then got up and dressed very quickly. My maid helped me and, as she had guessed what my plan was, she was highly amused.

Wrapped in my cloak, with a lace fichu over my head, I joined Mayer in the smoking room and then we both got into his hansom.

“Come to me in an hour’s time,” I said in a low voice to my maid.

“Where are you going?” asked Mayer, perfectly stupefied.

“To the theater ... quick ... quick...!” I answered.

The cab started and I then explained to him that if I had stayed at home, neither Dr. Parrot nor Dr. Vintras would have let me act upon any account.

“The die is cast now,” I added, “and we shall see what happens.”

When once I was at the theater I took refuge in the manager’s private office, in order to avoid Dr. Parrot’s anger. I was very fond of him and I knew how wrongly I was acting toward him, considering the inconvenience to which he had put himself in making the journey specially for me in response to my summons. I knew, though, how impossible it would have been to have made him understand that I felt really better, and that in risking my life I was really only risking what was my own to dispose of as I pleased.

Half an hour later my maid joined me. She brought with her a letter from Dr. Parrot, full of gentle reproaches and furious advice, finishing with a prescription, in case of a relapse. He was leaving an hour later and would not even come and shake hands with me. I felt quite sure, though, that we should make it all up again on my return. I then began to prepare for my rôle in “L’Etrangère.” While dressing, I fainted three times, but I was determined to play quand-même.

The opium that I had taken in my potion made my head rather heavy. I arrived on the stage in a semiconscious state, delighted with the applause I received. I walked along as though I were in a dream and could scarcely distinguish my surroundings. The house itself I saw only through a luminous mist. My feet glided along on the carpet without any effort, and my voice sounded to me far away, very far away. I was in that delicious stupor that one experiences after chloroform, morphine, opium, or hasheesh.

The first act went off very well, but in the third act, just when I was to tell the Duchess de Septmonts (Croizette) all the troubles that I, Mrs. Clarkson, had gone through during my life, just as I should have commenced my interminable story I could not remember anything. Croizette murmured my first phrase for me, but I could only see her lips move without hearing a word. I then said quite calmly:

“The reason I sent for you here, madame, is because I wanted to tell you my reasons for acting as I have done, but I have thought it over and have decided not to tell you them to-day.”

Sophie Croizette gazed at me with a terrified look in her eyes, she then rose and left the stage, her lips trembling, and her eyes fixed on me all the time.

“What’s the matter?” everyone asked when she sank almost breathless into an armchair.

“Sarah has gone mad!” she exclaimed. “I assure you she has gone quite mad. She has cut out the whole of her scene with me.”

“But how?” everyone asked.

“She has cut out two hundred lines,” said Croizette.

“But what for?” was the eager question.

“I don’t know. She looks quite calm.”

The whole of this conversation which was repeated to me later on took much less time than it does now to write it down. Coquelin had been told and he now came on to the stage to finish the act. The curtain fell. I was stupefied and desperate afterwards on hearing all that people told me. I had not noticed that anything was wrong, and it seemed to me that I had played the whole of my part as usual, but I was really under the influence of the opium. There was very little for me to say in the fifth act, and I went through that perfectly well. The following day the accounts in the papers sounded the praises of our company but the piece itself was criticised. I was afraid at first that my involuntary omission of the important part in the third act was one of the causes of the severity of the press. This was not so, though, as all the critics had read and re-read the piece. They discussed the play itself, and did not mention my slip of memory.

The Figaro, which was in a very bad humor with me just then, had an article from which I quote the following extract:

“‘L’Etrangère’ is not a piece in accordance with the English taste. Mlle. Croizette, however, was applauded enthusiastically and so were Coquelin and Febvre. Mlle. Sarah Bernhardt, nervous as usual, lost her memory.”

He knew perfectly well, worthy Mr. Johnson,[3] that I was very ill. He had been to my house and seen Dr. Parrot, consequently he was aware that I was acting in spite of the faculty in the interests of the Comédie Française. The English public had given me such proofs of appreciation that the Comédie was rather affected by it, and the Figaro, which was at that time the organ of the Théâtre Française, requested Johnson to modify his praises of me. This he did the whole time that we were in London.

My reason for telling about my loss of memory, which was quite an unimportant incident in itself, is merely to prove to authors how unnecessary it is to take the trouble of explaining the characters of their creations. Alexandre Dumas was certainly anxious to give us the reasons which caused Mrs. Clarkson to act as strangely as she did. He had created a person who was extremely interesting and full of action as the play proceeds. She reveals herself to the public, in the first act, by the lines which Mrs. Clarkson says to Mme. de Septmonts. “I should be very glad, madame, if you would call on me. We could talk about one of your friends, M. Gérard, whom I love perhaps, as much as you do, although he does not perhaps care for me as he does for you.”

That was quite enough to interest the public in these two women. It was the eternal struggle of good and evil, the combat between Vice and Virtue. But it evidently seemed rather commonplace to Dumas, ancient history, in fact, and he wanted to rejuvenate the old theme by trying to arrange for an orchestra with organ and banjo. The result he obtained was a fearful cacophony. He wrote a foolish piece, which might have been a beautiful one. The originality of his style, the loyalty of his ideas, and the brutality of his humor sufficed for rejuvenating old ideas, which, in reality, are the eternal basis of all tragedies, comedies, novels, pictures, poems, and pamphlets. It was Love between Vice and Virtue. Among the spectators who saw the first performance of “L’Etrangère” in London, and there were quite as many French as English present, not one remarked that there was something wanting, and not one of them said that he had not understood the character.

I talked about it to a very learned Frenchman.

“Did you notice the gap in the third act?” I asked him.

“No,” he replied.

“In my big scene with Croizette?”

“No.”

“Well, then, read what I left out,” I insisted.

When he had read this he exclaimed: “So much the better. It’s very dull, all that story, and quite useless. I understand the character without all that rigmarole and that romantic history.”

Later on, when I apologized to Dumas fils for the way in which I had cut down his play, he answered: “Oh, my dear child, when I write a play I think it is good, when I see it played I think it is stupid, and when any anyone tells it to me, I think it is perfect, as the person always forgets half of it.”

The performances given by the Comédie Française drew a crowd nightly to the Gaiety Theater, and I remained the favorite. I mention this now with pride, but without any vanity. I was very happy and very grateful for my success, but my comrades had a grudge against me on account of it, and hostilities began in an underhand, treacherous way.

Mr. Jarrett, my adviser and agent, had assured me that I should be able to sell a few of my works, either my sculpture or paintings. I had, therefore, taken with me six pieces of sculpture and ten pictures, and I had an exhibition of them in Piccadilly. I sent out invitations, about a hundred in all.

His Royal Highness, the Prince of Wales, let me know that he would come with the Princess of Wales. The English aristocracy and the celebrities of London came to the inauguration. I had sent out only a hundred invitations, but twelve hundred people arrived, and were introduced to me. I was delighted and enjoyed it all immensely.

Mr. Gladstone did me the great honor of talking to me for about ten minutes. With his genial mind he spoke of everything in a singularly gracious way. He asked me what impression the attacks of certain clergymen on the Comédie Française and the damnable profession of dramatic artistes, had made on me. I answered that I considered our art quite as profitable, morally, as the sermons of Catholic and Protestant preachers.

“But will you tell me, mademoiselle,” he insisted, “what moral lesson you can draw from ‘Phèdre’?”

“Oh, Mr. Gladstone,” I replied, “you surprise me! ‘Phèdre’ is an ancient tragedy; the morality and customs of those times belong to a perspective quite different from ours, and different from the morality of our present society. And yet in that there is the punishment of the old nurse Œnone, who commits the atrocious crime of accusing an innocent person. The love of Phèdre is excusable on account of the fatality which hangs over her family, and descends pitilessly upon her. In our times we should call that fatality atavism, for Phèdre was the daughter of Minos and Pasiphæ. As to Theseus, his verdict, against which there could be no appeal, was an arbitrary and monstrous act, and was punished by the death of that beloved son of his who was the sole and last hope of his life. We ought never to cause what is irreparable.”

“Ah!” said the Grand Old Man, “you are against capital punishment?”

“Yes, Mr. Gladstone.”

“And quite right, mademoiselle.”

Frederic Leighton then joined us and with great kindness complimented me on one of my pictures, representing a young girl holding some palms. This picture was bought by Prince Leopold.

My little exhibition was a great success, but I never thought that it was to be the cause of so much gossip and of so many cowardly side thrusts, until finally it led to my rupture with the Comédie Française.

I had no pretensions either as a painter or a sculptor, and I exhibited my works for the sake of selling them, as I wanted to buy two little lions and had not money enough. I sold the pictures for what they were worth, that is to say, at very modest prices.

Lady H—— bought my group “After the Storm.” It was smaller than the large group I had exhibited two years previously at the Paris Salon, and for which I had received a prize. The smaller group was in marble, and I had worked at it with the greatest care. I wanted to sell it for £160, but Lady H—— sent me £400 together with a charming note, which I venture to quote. It ran as follows:

Do me the favour, Madame, of accepting the enclosed £400 for your admirable group “After the Storm.” Will you also do me the honour of coming to lunch with me and afterwards you shall choose for yourself the place where your piece of sculpture will have the best light.

ETHEL H——.

This was Tuesday and I was playing in “Zaïre” that evening, but Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday I was not acting. I had money enough now to buy my lions, so without saying a word at the theater, I started for Liverpool. I knew there was a big menagerie there, Cross’s Zoo, and that I should find some lions for sale.

The journey was most amusing, as although I was traveling incognito, I was recognized all along the route and was made a great deal of.

Three gentlemen friends and Hortense Damain were with me, and it was a very lively little trip. I know that I was not shirking my duties at the Comédie, as I was not to play again before Saturday, and this was only Wednesday.

We started in the morning at 10.30 A.M. and arrived in Liverpool about 2.30. We went at once to Cross’s, but could not find the entrance to the house. We asked a shopkeeper at the corner of the street, and he pointed to a little door which we had already opened and closed twice, as we could not believe that was the entrance.

I had seen a large iron gateway with a wide courtyard beyond, and we were in front of a little door leading into quite a small, bare-looking room, where we found a little man.

“Mr. Cross?” we said.

“That’s my name,” he replied.

“I want to buy some lions,” I then said.

He began to laugh, and he asked,

“Do you really, mademoiselle? Are you so fond of animals? I went to London last week to see the Comédie Française, and I saw you in ‘Hernani’ ...”

“It wasn’t from that you discovered that I liked animals?” I said to him.

“No, it was a man who sells dogs in St. Andrew’s Street who told me; he said you had bought two dogs from him and that if it had not been for the gentleman who was with you, you would have bought five.”

He told me all this in very bad French, but with a great deal of humor.

“Well, Mr. Cross,” I said, “I want two lions to-day.”

“I’ll show you what I have,” he replied, leading the way into the courtyard where the wild beasts were. Oh, what magnificent creatures they were! There were two superb African lions with shining coats and powerful-looking tails which were beating the air. They had only just arrived and they were in perfect health, with plenty of courage for rebellion. They knew nothing of the resignation which is the dominating stigma of civilized beings.

“Oh, Mr. Cross,” I said, “these are too big, I want some young lions.”

“I haven’t any, mademoiselle.”

“Well, then, show me all your animals.”

I saw the tigers, the leopards, the jackals, the chetahs, and the pumas, and I stopped in front of the elephants. I simply adore them, and I should have liked to have a dwarf elephant. That has always been one of my dreams, and perhaps some day I shall be able to realize it.

Cross had not any, though, so I bought a chetah. It was quite young and very droll; it looked like a gargoyle on some castle of the Middle Ages. I also bought a dog wolf, all white with a thick coat, fiery eyes, and spearlike teeth. He was terrifying to look at. Mr. Cross made me a present of six chameleons which belonged to a small race and looked like lizards. He also gave me an admirable chameleon, a prehistoric, fabulous sort of animal. It was a veritable Chinese curiosity and changed color from pale green to dark bronze, at one minute slender and long like a lily leaf, and then all at once puffed out and thick-set like a toad. Its lorgnette eyes, like those of a lobster, were quite independent of each other. With its right eye it would look ahead, and with its left eye it looked backward. I was delighted and quite enthusiastic over this present. I named my chameleon “Cross-ci Cross-ça,” in honor of Mr. Cross.

We returned to London with the chetah in a cage, the dog wolf in a leash, my six little chameleons in a box, and “Cross-ci Cross-ça” on my shoulder, fastened to a gold chain we had bought at a jeweler’s. I had not found any lions but I was delighted all the same. My domestics were not as pleased as I was. There were already three dogs in the house: Minniccio who had accompanied me from Paris, Bull and Fly, bought in London. Then there was my parrot, Bizibouzon, and my monkey, Darwin.

Mme. Guérard screamed when she saw these new guests arrive. My butler hesitated to approach the dog wolf, and it was all in vain that I assured them that my chetah was not dangerous. No one would open the cage, and it was carried out into the garden. I asked for a hammer in order to open the door of the cage that had been nailed down, thus keeping the poor chetah a prisoner. When my domestics heard me ask for the hammer, they decided to open it themselves. Mme. Guérard and the women servants watched from the windows. Presently the door burst open, and the chetah, beside himself with joy, sprang like a tiger out of his cage, wild with liberty. He rushed at the trees, made straight for the dogs, who all four began to howl with terror. The parrot was excited, and uttered shrill cries and the monkey, shaking his cage about, gnashed his teeth to distraction. This concert in the silent square made the most prodigious effect. All the windows were opened and more than twenty faces appeared above my garden wall, all of them inquisitive, alarmed, or furious. I was seized with a fit of uncontrollable laughter, and my friend Louise Abbéma; Nittis, the painter, who had come to call on me, was in the same state, and Gustave Doré, who had been waiting for me ever since two o’clock. Georges Deschamp, an amateur musician, with a great deal of talent, tried to note down this Hoffmanesque harmony, while my friend, Georges Clairin, his back shaking with laughter, sketched the never-to-be-forgotten scene.

The next day in London the chief topic of conversation was the Bedlam that had been let loose at 77, Chester Square. So much was made of it that our dean, M. Got, came to beg me not to make such a scandal, as it reflected on the Comédie Française. I listened to him in silence and when he had finished I took his hands.

“Come with me and I will show you the scandal,” I said. I conducted him into the garden.

“Let the chetah out!” I said, standing on the steps like a captain ordering his men to take in a reef.

When the chetah was free the same mad scene occurred again as on the previous day.

“You see, M. le Doyen,” I said, “this is my Bedlam.”

“You are mad,” he said, kissing me, “but it certainly is irresistibly comic,” and he laughed until the tears came when he saw all the heads appearing above the garden wall.

The hostilities continued, though by means of scraps of gossip retailed by one person to another and from one set to another. The French Press took it up and so did the English Press. In spite of my happy disposition and my contempt for ill-natured tales, I began to feel irritated. Injustice has always roused me to revolt, and injustice was certainly having its fling. I could not do a thing that was not watched and blamed.

One day I was complaining of this to Madeleine Brohan, whom I loved dearly. That adorable artiste took my face in her hands, and looking into my eyes, said: “My poor dear, you can’t do anything to prevent it. You are original without trying to be so. You have a dreadful head of hair that is naturally curly and rebellious, your slenderness is exaggerated, you have a natural harp in your throat, and all this makes of you a creature apart, which is a crime of high treason against all that is commonplace. That is what is the matter with you physically. Now for your moral defects. You cannot hide your thoughts, you cannot stoop to anything, you never accept any compromise, you will not lend yourself to any hypocrisy, and all that is a crime of high treason against society. How can you expect under these conditions not to arouse jealousy, not to wound people’s susceptibilities, and not to make them spiteful? If you are discouraged because of these attacks, it will be all over with you, as you will have no strength left to withstand them. In that case I advise you to brush your hair, to put oil on it, and so make it lie as sleek as that of the famous Corsican, but even that would never do, for Napoleon had such sleek hair that it was quite original. Well, you might try to brush your hair as smooth as Prudhon’s,[4] then there would be no risk for you. I would advise you,” she continued, “to get a little stouter and to let your voice break occasionally, then you would not annoy anyone. But if you wish to remain yourself, my dear, prepare to mount on a little pedestal made of calumny, scandal, injustice, adulation, flattery, lies, and truths. When you are once upon it, though, do the right thing, and cement it by your talent, your work, and your kindness. All the spiteful people who have unintentionally provided the first materials for the edifice will kick it, then, in hopes of destroying it. They will be powerless to do this, though, if you choose to prevent them; and that is just what I hope for you, my dear Sarah, as you have an ambitious thirst for glory. I cannot understand that, myself, as I like only rest and shade.”

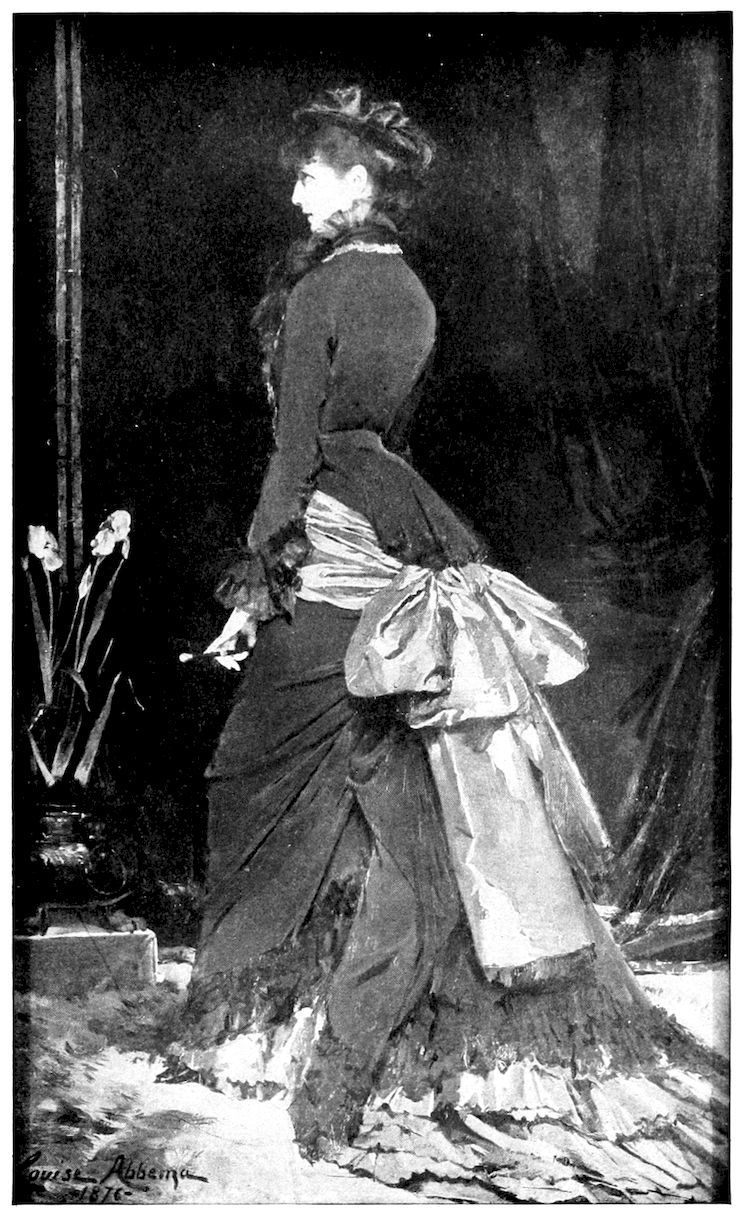

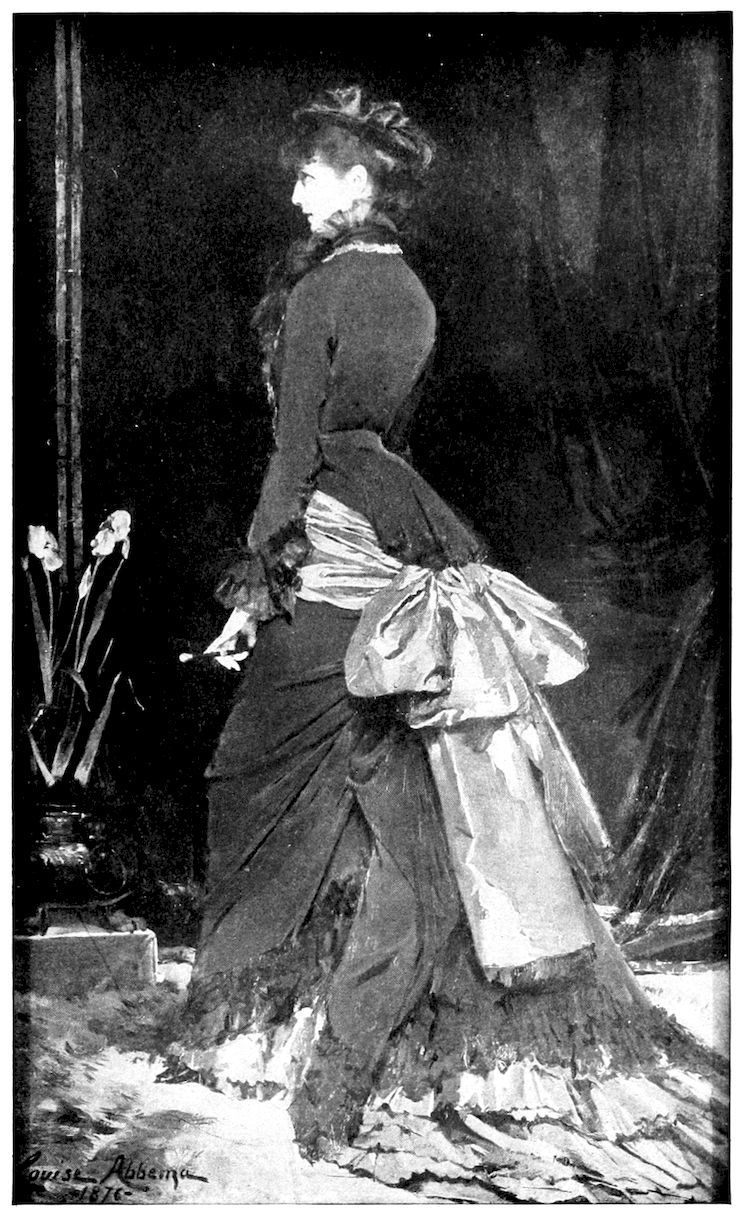

SARAH BERNHARDT, FROM AN OIL PAINTING BY MLLE. LOUISE ABBÉMA.

I looked at her with envy, she was so beautiful with her liquid eyes, her face with its pure, restful lines and her weary smile. I wondered in an uneasy way if happiness were not rather in this calm tranquillity, in the disdain of all things. I asked her gently if this were so, for I wanted to know, and she told me that the theater bored her, that she had had so many disappointments. She shuddered when she spoke of her marriage, and as to her motherhood, that had only caused her sorrow. Her love affairs had left her affections crushed and physically disabled. The light seemed doomed to fade from her beautiful eyes, her legs were swollen, and could scarcely carry her. She told me all this in the same calm, half weary tone.

What had charmed me only a short time before chilled me to the heart now, for her dislike to movement was caused by the weakness of her eyes and her legs, and her delight in the shade was only the love of that peace which was so necessary to her, wounded as she was by the life she had lived.

The love of life, though, took possession of me more violently than ever. I thanked my dear friend, and profited by her advice. I armed myself for the struggle, preferring to die in the midst of the battle rather than to end my life regretting that it had been a failure. I made up my mind not to weep over the base things that were said about me, and not to suffer any more injustices. I made up my mind, too, to stand on the defensive and very soon an occasion presented itself.

“L’Etrangère” was to be played for the second time at a matinée, June 21, 1879. The day before I had sent word to Mayer that I was not well and that as I was playing in “Hernani” at night, I should be glad if he could change the play announced for the afternoon if possible. The receipts, however, were more than £400 and the Committee would not hear of it.

“Oh, well,” Got said to Mr. Mayer, “we must give the rôle to some one else if Sarah Bernhardt cannot play. There will be Croizette, Madeleine Brohan, Coquelin, Febvre, and myself in the cast, and, hang it all, it seems to me that all of us together will make up for Mlle. Bernhardt.”

Coquelin was requested to ask Lloyd to take my part, as she had played this rôle at the Comédie when I was ill. Lloyd was afraid to undertake it, though, and refused. It was decided to change the play, and “Tartuffe” was given instead of “L’Etrangère.” Nearly all of the public, however, asked to have their money refunded, and the receipts, which would have been about £500, only amounted to £84.

All the spite and jealousy now broke loose, and the whole company of the Comédie, more particularly the men, with the exception of Mr. Worms, started a campaign against me. Francisque Sarcey, as drum major, beat the measure with his terrible pen in his hand. The most foolish, slanderous, and stupid inventions and the most odious lies took their flight like a cloud of wild ducks and swooped suddenly down upon all the newspapers that were against me. It was said that for a shilling anyone might see me dressed as a man; that I smoked huge cigars leaning on the balcony of my house; that at the various receptions where I gave one-act plays, I took my maid with me for the dialogue; that I practiced fencing in my garden, dressed as a pierrot in white, and that when taking boxing lessons, I had broken two teeth for my unfortunate professor.

Some of my friends advised me to take no notice of all these turpitudes, assuring me that the public could not possibly believe them. They were mistaken, though, for the public likes to believe bad things about anyone, as these are always more amusing than the good things. I soon had a proof that the English public was beginning to believe what the French papers said. I received a letter from a tailor asking me if I would consent to wear a coat of his make when I appeared in masculine attire, and not only did he offer me this coat for nothing, but he was willing to pay me a hundred pounds if I would wear it. This man was quite an ill-bred person, but he was sincere. I received several boxes of cigars, and the boxing and fencing professors wrote to offer their services gratuitously. All this annoyed me to such a degree that I resolved to put an end to it. An article by Albert Wolff in the Paris Figaro caused me to take steps to cut matters short.

And I wrote in reply to it as follows:

ALBERT WOLFF, FIGARO, PARIS:

And you, too, my dear M. Wolff—you believe in such insanities? Who can have been giving you such false information? Yes, you are my friend, though, for in spite of all the infamies you have been told you have still a little indulgence left. Well, then, I give you my word of honor that I have never dressed as a man here in London. I did not even bring my sculptor costume with me. I give the most emphatic denial to this misrepresentation. I only went once to the exhibition which I organized, and that was on the opening day, for which I had only sent out a few private invitations, so that no one paid a shilling to see me. It is true that I have accepted some private engagements to act, but you know that I am one of the most poorly paid members of the Comédie Française. I certainly have the right, therefore, to try to make up the difference. I have ten pictures and eight pieces of sculpture on exhibition. That, too, is quite true, but as I brought them over here to sell I really must show them. As to the respect due to the House of Molière, dear M. Wolff, I lay claim to keeping that in mind more than anyone else, for I am absolutely incapable of inventing such calumnies for the sake of slaying one of its standard-bearers. And now, if the stupidities invented about me have annoyed the Parisians and if they have decided to receive me ungraciously on my return, I do not wish anyone to be guilty of such baseness on my account, so I will send in my resignation to the Comédie Française. If the London public is tired of all this fuss and should be inclined to show me ill-will instead of the indulgence hitherto accorded me, I shall ask the Comédie to allow me to leave England in order to spare our company the annoyance of seeing one of its members hooted at and hissed. I am sending you this letter by wire, as the consideration I have for public opinion gives me the right to commit such folly, and I beg you, dear M. Wolff, to accord to my letter the same honor as you did to the calumnies of my enemies.

With very kind regards,

Yours sincerely,

SARAH BERNHARDT.

This telegram caused much ink to flow. While treating me as a spoiled child, people generally agreed that I was quite right. The Comédie was most amiable, Perrin, the manager, wrote me an affectionate letter begging me to give up my idea of leaving the company. The women were most friendl