The Honours Year

I was warned that honours year is going to be the toughest year in my tertiary education. Robb told me that he drank so much coffee during his honours year that he developed kidney stones. That is right to the very letter of the word. It is a hell of a sprint from Day 1. Some stretches were almost like a fight for survival. I got to learn the limits of my physical body, how little sleep I needed and not wanted, how much caffeine I can load into my body on a daily basis. I learnt that I only needed 4 hours of sleep a day and can execute a 70-hour day if needed. I learnt that I can survive a meal a day for a week. I learnt that I can drink 3 cups of lattes and consumed 10 teabags a day, every day, without suicide. I learnt that practically none of the original paragraph and nearly no single sentence of the first draft of my thesis made it into the final version in verbatim. My hair started to grey in this very year.

Honours programme began at a much earlier date in zoology than other departments as we had to attend a 2-week Masters level statistics course which was held 1-week in Melbourne and 1-week in Monash University. To me then, it was a waste of time. I could hardly pick up anything except maybe a few key ideas like randomization tests and so on. The biggest reason for me was that there was no data to use and the course is primarily focused on ecology which is not my interest at all. Although each day was a morning lecture and afternoons were computer classes, I skipped all computer classes. I was more tied up with the visa process and my own reading. Furthermore, by the time I needed to use statistics, I would have forgotten all of them. Frankly, I was not too happy about spending this time. It will be useful for ecologists but not for me.

Kevin is a lactation biologist who had been in this very area since his own doctoral days. Over the years I was with him, his enthusiasm for science is infectious. Both Joly and I agreed that he loves his science. There are a few things intriguing about lactation and the way he approached it. For Kevin, he just wants to deal with lactation and all his work was on mammary glands regardless of animals. So far, he had worked with pigs, cows, mice, rats, wallabies, fur seals – all mammary glands. I can even call him an organ-specific scientist. This is in contrast with Marilyn Renfree whom I call as animal-specific scientist. She is a wallabologist, solely concentrating on everything a wallaby has to offer – growth, reproduction, etc. Comparing and contrasting these 2 scientists really helped me to shape my view and direction of science.

Thomas Kuhn argued in his book, The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, that scientific knowledge is essentially based on paradigms – some culturally accepted ways to look at nature – rather than looking at nature unobstructively. It is like saying that we see a person but feel the person’s bodily warmth. Physically speaking, there is no reason why we cannot feel a person and see his warmth when all are just different frequencies of electromagnetic radiation. However, we are obstructed and limited by our sensory organs. Similarly, in science, we are limited by prior concepts, prejudices and tools. All these formed the underlying assumptions that we bring with us when looking at other research or even our own. In the context of Kevin and Marilyn, there is really no advantage of one or another direction but perhaps what is most applicable for the current work and also bearing in mind the existence of the other. As my story will later reveal, evaluating these assumptions may be very challenging as it may strike at the core of someone else’s belief.

My honours thesis is to elucidate the roles of insulin, prolactin, and glucocorticoid in mouse lactogenesis. That is to say, what the roles are played by each hormone to enable the mouse mammary tissues to kick off in the direction of producing milk. I am not trying to looking into any more than the initial part of milk production, certainly not the sustenance of milk production.

The term lactogenesis refers to the starting of lactose synthesis and is a term coined by Peter Hartmann, Kevin’s PhD supervisor, one of my academic grandfathers that is, where he measured lactose production. We know what all 3 hormones are needed for lactogenesis but it was not clear how these 3 hormones interact towards this purpose and my project was on that. There were 2 parts to my thesis. Firstly, I used casein gene as a marker for lactogenesis instead of lactose. Casein is a predominant milk protein; thus, easier to measure using standard molecular techniques such as PCR than measuring sugars. So indirectly, I am actually equating “casein-genesis” as lactogenesis. I was to show that casein synthesis can only take place in the presence of all 3 hormones and not in the presence of 2 of the 3 hormones. Secondly, I elucidated the role of each hormone in the presence of the other 2 using microarrays. For example, by comparing the total gene expression (transcriptome) of tissues treated by all 3 hormones to that of insulin and glucocorticoid, I can understand the influence of prolactin.

Initially, this was really simple mathematical logic, prolactin = (insulin + prolactin + glucocorticoid) – (insulin + glucocorticoid). But as I talked to others, I realized that it was not that simple as there are interacting effects. For example, insulin and glucocorticoid are not just insulin and glucocorticoid but the interaction between insulin and glucocorticoid must be accounted. This expanded the mathematical model of the 3 hormones into insulin + prolactin + glucocorticoid + (insulin x prolactin) + (insulin x glucocorticoid) + (prolactin x glucocorticoid) + (insulin x prolactin x glucocorticoid), 7 factors in all. I was working with this model. Looking back, it was this very initial training that formed the basis of my multivariate statistical understanding.

Kevin’s lab was sponsored by the Cooperative Research Centre for Innovative Dairy Products. We just called it Dairy CRC or CRC for short. Cooperative Research Centre was a scheme by the Australian government to bring the academics and the industry closer together. In collaboration, they put up a CRC proposal and if approved, the CRC would be awarded 14 million dollars over 7 years by the government for a start-up. The rest will come from the industry. Run like a company, every CRC almost acts like a micro-grant agency for those research groups under it. In all, the Diary CRC was a 70 million dollars research consortium which funded a number of projects in view to promote use and novel products from Australian diary industry. Our research partners included those in Sydney University, Garven Institute of Medical Research, and CSIRO Livestock Industry.

Being in a CRC for my honours year was enriching. Tangibly, I was awarded an honours scholarship of $2500 based on my final year results. Although it was not a large sum, it sure helped to pay a few months of rent. More importantly, it was the expansion of my worldview and vision of the research world. With my computing background, I could table discussions on open-source licences and digital signatures. Electronic records were a major problem for me as my data and analyses are too much to print out and paste into traditional logbooks. It was also about then, mid-2003, that SCO filed a patent lawsuit against IBM with respect to Linux source codes. This case brought the issue of open-source and its licences into legal perusal, especially General Public License (GLP). Being a supporter of open-source and for the purpose of self-preservation, I felt the need to keep myself informed of these events. As a result, I had spent almost a disproportionate amount of time reading up on all these legal issues.

Another thing that CRC showed me was the importance of online communications. Besides occassional phone communications and an annual conference with a few sporadic meetups, the entire consortium spanning from Melbourne to Brisbane (about 2000 kilometres) depended largely on email communications. I had my fair share of discussing my ideas with regards to electronic records, open-source licences and digital signatures via email. This really made me consider that proper online, asynchronous communication is a vital skill for the future and that proved to be true for me.

It was also about then that I decided to licence most of my computer codes in GPL or its variants whenever possible. Science is in nature an open-source, fully collaborative pursuit but commerce is not for giving up things for free. This is a tough balance but it is a balance that all scientists have to make on a daily basis.

There are 2 unique aspects about Zoology’s honours programme. The first is a grant writing exercise where we had to write a grant for your project and we were not supposed to ask for more than $30000. Each grant will be reviewed by 2 persons – 2 other honours students – and would come together as a panel to decide on the grant quantum in terms of mint sweets – one mint sweet was $1000. The panel was chaired by Laura Parry, one of our honours coordinators. This was to let us have a feel of how grant reviews are like and the difficulty of getting any money at all. It was a challenging panel as the total quantum asked for in the grant was about 300 thousand but there was only 100 thousand in available grants (100 mint sweets so as to say). Bojun, one of the honours students, insisted that no grant awarded should be more than $8000 and she derived this number by dividing 100 thousand by the number of grants. At the same time, we also agreed to award something for every grant so that everyone had at least a candy. It was an interesting exercise and rather brutal as well.

I asked for 27 thousand and got 3 thousand instead – for a pilot project. Only 1 grant was awarded in full as she asked for only a thousand dollars. This really got me thinking about my future and possibly the directions I wanted to take. If grants are so difficult to get, how could I survive with the least amount of money? Eventually, this very thought shaped my doctoral direction.

The second thing was that Zoology had teamed up with Botany to have a series of honours seminars where we had talks on the larger aspect of science – science and politics especially. We had speakers like Adrienne Clark who was a former chair of CSIRO and consulting scientist in United Nations and Nancy Millis who had been on Australian stamp and was the Chancellor of La Trobe University from 1992 to 2006. Both are considered to be National Living Treasures. The emphasis of these talks was not on science itself but on the landscape, ecology and politics of science which I found to be enlightening.

During the course of my honours, I had to give 2 departmental seminars – one in the beginning to describe our project and another at the end. Using what I learnt in NCC back then, my slides were as brief as possible and Kevin made sure that every phrase in every slide was well explained and essential. A key to good presentation was not to allow anyone to have to read the slides. I remembered that I rehearsed so many times that I really got sick of my own presentation before I stood up to present to the department. If all did not matter, this amount of practices made me want to get it done and over with. That sure helped in calming every of my nerves. I think I rehearsed at least 15 times and Kevin was there every time along the way. His support was relentless and I truly appreciated that. I made a note to myself then that if I ever had my own students, I will do the same for them.

The following day, Matthew Digby, my honours co-supervisor, came and told me that the comment he heard from others while sitting through my presentation was “I had never heard such clear explanation of microarrays before.” The practices were well worth it.

The inaugural Australian Undergraduate Students’ Computing Conference finally took place during my honours year – about September 2003. It is really just a general feel of accomplishment when I see it all happening. Personally, I published my first peer-reviewed manuscript titled “Architecture of an Open-Sourced, Extensible Data Warehouse Builder: InterBase 6 Data Warehouse Builder (IB-DWB)” on my Advanced Diploma in Computing project.

Although AUSCC only survived for 3 years from 2003 to 2005, we had left behind a legacy that something like this could be done. Certainly, undergraduates are able to do something useful. Subsequently, we were interviewed by Australian Broadcasting Corporation on AUSCC as they were doing a series on “Smart Societies”.

The convocation for my bachelor degree was 16th December 2003, which happened to be the hottest day of that year. Mum and Melvin touched down at Tullamarine airport at about 8.20am that day, after about an hour delay. It had been almost 1½ years since I last saw them and was pretty excited. That turned out to be a rather exhausting day – partially by the roasting sun. Our convocation was about 4pm in the afternoon. Personally, I thought that we were more interested in taking photographs in our gowns, though stewing in our own sweat, then the actual ceremony. After the event, Kevin and Mary took me, Melvin and mum to Brunetti’s for some cakes and coffee. That was the only time in memory that I had coffee with Kevin out of the lab context.

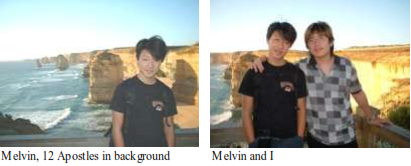

Over the next few days, we went to Great Ocean Road, Puffing Billy, and St Kildas beach, other than walking in the city. Joly also took them around Chapel Street. I love Melvin – he is the only brother I have. Though I may be angry with him at times, I still love him very much. Mum told me that I made him cry in Melbourne for not remembering the directions.

It was surprising how little I missed home until mum and Melvin came over. I saw Melvin and wanted to hug him tightly. I knew that I could be very harsh to him at times but I want him to be strong and able to survive the world himself – I cannot be always around to protect him. There was once I got him to carry out the trash and he locked himself outside until mum went out to look for him. Of course, he was scared at that time. Nevertheless, I tried not to show on my face. I was not sure even today, if that was the correct thing or expression to show but he has to be strong – perhaps even stronger than me. Despite all, I still love him very much.

They were only in Melbourne for about a week and it was at the airport sending them off that I felt sad and really missed them for the very first time. I remembered that I just sent them off to the passport control from a distance. As they started walking towards the checkpoint, I turned and walk in the opposite direction. For a moment, I could not bear to see them off – sourness swelled up in my eyes as I walked off to board the bus back to the city. I was moody and down for the rest of the day.

In the summer of 2003, we decided on a road trip to Wilson Promontory – the southern-most top of mainland Australia. That was the last thing before the turning point in many of our lives. From then on, Eugene Khoo (formally from Ngee Ann Polytechnic and did genetics honours with Edwin but in a different laboratory) was no longer close to us or part of the dinner gang. Over the subsequent 3 months since the road trip, Edwin broke up with Selen and Joly broke up with her boyfriend in Singapore. Edwin and Joly got together. Subsequently, Eugene broke up with his girlfriend, Eva, from Taiwan, and also terminated his PhD candidature. Selen eventually got a scholarship for her PhD but rejected it.

The only thing that was confirmed was that there was a rumour about Edwin and Joly and that got to Selen back in Singapore. Both Edwin and Joly denied violently then. Somehow Eugene, Eva, Pauline and Lim Bock (Joly’s housemates) were all wrapped in this big smog. We had a BBQ at Han Sen’s place and that was the last time everyone was on friendly terms though the rumour was already in the air and started to break things apart. I have no idea what transpired in Singapore when everyone was back for summer break but when Edwin and Joly were back in February 2004, they were essentially together. I thought that I was overly sensitive but it was Robin that alerted me that there was something going on between Edwin and Joly – the vibes, he said. Till today, what had happened is still a mystery to me.

This shook the very core of my friendship group in Melbourne. I was churning the events in my mind. At the same time, my honours work was not getting much headway and I was desperate trying to get enough RNA to run my microarrays. My literature review and magazine essay (the given broad topic was on how DNA technology changed society) did not score as well as I wanted. I started to read more papers and re-read a good part of the papers I cited in my literature review – often reading 10 to 15 papers a day. Part of me was trying to get my mind off thinking about what had happened, the other part of out of necessity. That was the time where I started to drink about 3 cups of coffee and 5 cups of double teabags every day. My hair started to grey in that summer.

By the time our half-year lease ran out in the City, Joel and I decided to experience staying in the suburbs. I thought that was a good choice as both of us hardly met each other due to our honours. Certainly, we no longer cook and eat together like the year before. For me, things were getting a little awkward though I was to bear some of the blame for even eating my breakfast in my room. There was a mutual feeling that if this was to go on, we will really become hi-bye friends. We did not really say that we do not want to live together but it was rather unsaid that it might be for the better that way. We even went to look at vacancy advertisements together so it was not the case of one not wanting to live with the other. We just thought that 1½ years as roommates, then housemates, was enough. I moved to Elsteinwick, off Kooyong Road, while Joel moved to Carnegie.

It was a shock to me during the first 2 weeks in Elsteinwick – it was so dead and empty and quiet at night. I had gotten so used to the city life that I was on cold turkey. It was stressful. A large part of me was rejecting this suburban lifestyle where the roads were dead by 6pm. It was a strange feeling back then and I could not pin-point the reason why I got so stressful. I remembered that there were days where I clenched onto my stress ball until my hand trembled and knuckles turned white. Perhaps it was the change of environment and events and that everyone else was back in Singapore that really froze me from inside – it was a pure sense of loneliness. I cried.

I started to leave for school earlier and earlier until the day I took the first tram to school at 5.20am and reached school at 6.15am. I would leave the office at 8.30pm and got home at 9.45pm by bus. Luckily it was summer then and did not felt as bad as what it could be. At home, I was watching Sex and the City every night.

It took me about 3 weeks to ease into the routine. Looking back, Elsteinwick was not that rural. There are restaurants and coffee outlets that opened into the night but I guessed the environment was just a precipitating or triggering factor – it was the chill of emotions that got into me.

Not sure what did I really love about the 25th Lorne Genomic Conference – the desserts, the food, the cheeses and wine, the company or what. Well, certainly not the talks per se – they were too much for me to handle. Lorne Conferences are a series of conferences held back to back of each other and there is really just a company to run these conferences. Kevin organized the entire lab to go for the conference and we rented a beach house. A postdoc from Marilyn’s lab, Danny Park, was also with us but he got a tent instead. With Sonia and Cate running most of the arrangements, everything was fine. Lorne is a town along Great Ocean Road, between Torquay and Apollo Bay. It was beautiful. The food was certainly too much and I tasted my first “Death by Chocolate” there. It is a cake – chocolate crusted chocolate mudcake, with thick chocolate fudge and topped with a chocolate truffle. No wonder it is called “Death by Chocolate” – you can die eating it without proper hydration. A slice is filling.

Poster sessions were scheduled for every evening, served with wine and cheeses – as many as 8 cakes of cheeses with 10 or more types of wines to go around. That was where I learnt a critical rule of posters – make sure that it is readable and understandable after 3 glasses of wine. In addition to that, lab equipment and consumable suppliers like Invitrogen and Qiagen sponsored beer on the tap. Conference banquet was on the very last night. That was where Cate was explaining the “sausage in the hallway” analogy – a penis of reasonable thickness is more important than its length. I believed that Sonia will still remember how drunk I got myself into – at the start of the banquet, I was drinking wine from a glass. By the end of it, I was drinking from a bottle and thirst was quenched with beer. I would have estimated that I drank about 3 bottles of mixed wine and glasses of beer. Ended up vomiting on the beach and a severe hangover the very next day where we had to drive back to Melbourne. Sonia was the designated driver. I recalled the terrible feeling of hangover in the vehicle, and had to take the train from Spencer station back to Elsteinwick. I am sure Sonia will remember this unglamourous incident from me.

Personally, I was enjoying the food and the company of everyone but also spent a large part of my time processing my microarray data for up-regulated genes. Nevertheless, after 5 days of perpetual eating and drinking, I felt the curse of the expanding girth.

Zoology has a wallaby yard at South Watana that is under the charge of Marilyn. As Kevin needed the mammary tissues from the wallabies, all of us were schedule for yard duties – about once a month, where we would go out to the yards and maintain the wallabies – either checking on their reproductive cycle or re-shuffling the animals. I learnt something peculiar about wallabies – they started mating immediately after summer solstice and they needed sleep to learn. You could open a gate during the day and the wallabies will not hope through it until the following day. It seems like they needed the night to learn that the gate was opened. Although it was a new experience at the yards, it was exhausting. For all these duties, Kevin got enough mammary tissues at various stages of wallabies’ lactation cycle to map the transcriptome using microarrays that Christophe designed.

During one of the trips from the yards with Elie, I started talking about the main difference that I felt being an international student compared to locals. It was finances. As an international student for more than a year, money is a critical factor – there was no safety net where we can run home to stay or get additional allowance. We run out of cash – we really run out of cash. By then, I grew to be very aware of my financial status at any point in time. That was probably the time where I started doing proper budgeting and saving plans where I set saving targets.

Although Matthew Digby was a co-supervisor for my honours, I hardly saw eye to eye with him. As a matter of fact, I learnt almost nothing from him that I could not pick up from Kevin and could really do without him at all. I think there were irreconcilable differences in our personalities to begin with. The only good thing I can say about Matthew was that he is a tentative listener in presentations and gave me constructive advices. Other than that, I really struggled to say anything good about him. It started pretty early in my honours year while we were discussing about microarray designs. To a certain extent, he had refused to take much notice of my views and Kevin’s till one fine day, he stuck a piece of paper on Kevin’s door which said “I think I got it” and drew the microarray experimental design which was exactly what Kevin had been talking about. To me, that was like claiming his stake in the project. When it came to microarray analysis, he almost demanded his methods to be followed and using Excel. To me, that was both difficult to document and seems rather unscientific at that point in time. In the end, I decided to venture with my own analysis – using my own programming skills and wrote my own scripts. This was the real initial reason why I had bought a book and started with Python programming. It gave me great pride and encouragement to say “I wrote those analysis scripts by myself” when he asked how I was to analyse my data without his help. Those scripts were appended to my honours thesis.

I think the last straw came when I was writing my honours thesis. All that Matthew did was to correct for my punctuation and some grammatical errors. I really needed more than that. He kept saying that I was not looking at my data more critically without suggesting how to do so. It was then that I decided that I was not going to have him as my supervisor for another project again. As such, he told me that I was “un-teachable”. Perhaps it was true that our personalities were incompatible – Kevin considered his arrogance to be “supremely confident” about himself but I considered that to be incorrigibly arrogant and self-centred, even though on hindsight, I do thank him for pushing me onto the road of learning Python programming.

During my honours year, Matthew had another honours student, Matthew Peirerra, who was a semester ahead of me. He got quite poor results and never contacted Matthew again as far as I was in the department. Matthew Digby considered him to be an ingrate but the views of some others suggested that Peirerra was not guided.

Neither Phil nor I remembered how we met each other or even know of each other’s existence. He was doing his final year in Bachelor of Biomedical Science while I was doing my honours, so there was no way we met in class. However, I do recall that our first meet up was in Union House and we had coffee together. That was around June 2004. Sometime down the road, he asked me to read his practical report and I had mercilessly pulled it apart. Later, he told me that he felt so confident about his work until I read it that he almost wanted to flush himself down the toilet. By about August 2004, Phil mentioned that he wanted to do an honours in reproduction biology and I suggested him to Mary. That was how we ended up in the same department and became good friends.

My honours thesis was due on April 30, 2004, and I had finished my first full draft by my birthday – March 30, 2004. It was an accomplishment even though almost the entire thesis had to be edited and almost re-written, except the literature review that had been extensively edited in the earlier part of the year. Then, I was faced with the task of synthesizing all my microarray results and discussing them in about 5 thousand words. It was a difficult task for me and I really did not know how to do it. For my first draft, I almost did not put in my microarray results but I did discuss them and that was Kevin’s main criticism – I was almost afraid to put down my microarray results. Kevin taught me how to summarize and describe my microarray results. Most importantly, he taught me how to describe my results without discussing them in the results section and how to discuss my results without extensive repetition of my results in the discussion section. As a consequence of that, almost every sentence in my results and discussion sections were changed but I truly enjoyed and able to submit my thesis with pride.

A large part of honours year was the cohort that I was in. Each of us were working on different and diverse areas – Bojun was the ant lady as she was doing colonization of Argentine ants; April Reside, whom I sold my Fujitsu laptop to, was the bat girl as she was working on bats; Michael Sale was a marine biologist so he was always out diving.

There were some interesting practices back then. There was the “last weekend survival kit”. Prior to the last weekend before our thesis was due, the previous batch will bake cookies and bought us chocolate bars to help us survive that weekend. At the start of every semester, the previous batch of honours students will have a departmental BBQ to welcome the latest batch of honours students. Hence, my batch got to organize the BBQ for Joly’s batch. Joly joined Kevin’s group as an honours student. It was almost like an initiation into the family. It was great.

As the day to submission got closer, each of us got more edgy. And as Edwin would have said it, the reflective indexes of our faces increased as it got oiler. It was without a strand of doubt that honours year is a sprint. Looking back, there is no other way of describing it. The end-point is the submission of the thesis. Like a 100 metre sprinter exhausting his last burst of energy, the worst that could happen was a last minute submission extension – there was just no energy left. After my adrenaline dropped to normal levels, I slept for 20 hours or so.

As I wrote the final pages of my honours thesis, on my way home in a tram one day, I had no idea why I thought of my late paternal grandfather who passed away when I was 14 and started weeping almost uncontrollably. I had to get off the tram at St Kildas and walked the rest of the way home, about 10 km in all, just to recompose myself. Thus, I decided to dedicate my honours thesis to him.

A decade ago, my Grandfather left abruptly.

Alone, he is, but with a smile.

I will never know what he dreamt of me.

Ten years, I had walked so far...

This day, twenty-five years ago, you first held me in your arms.

<