GROWING UP FAST

In early April 1944 I was still at school, supposed to matriculate in June. However, by mid-April Jews were forbidden to go to school, which was the first and last of the anti-Jewish measures which had my wholehearted support.

Rumours abounded, and one of these suggested that females who were married need not go to forced labour camps. Thus the greengrocer in our block of flats approached Mother and asked for my hand in marriage, - to his daughter. Without inspecting my bride to be, whom I never met, I declined the honour.

Another rumour was that as long as you were an apprentice you'll be allowed to finish your course. It was decided that I should become an apprentice lathe turner and Father and I went to the appropriate Government department to obtain their permit.

That was the first day when we had to wear our yellow star and obviously we were apprehensive about the reception we shall get from people on the street. The reaction was not easy to perceive as it was almost non-existent. People looked at us with some curiosity, but we were ignored and every body kept away from us. We were relieved to note that there was no hostile reaction to us, although we heard later that in some other places there were attacks on Jews by extremists. However, on that first day even we, who mercifully were ignored, definitely noticed a distinctive gulf between us who were marked with the Star of David and "they" who used to be our co-patriots and who suddenly regarded us as lepers.

I become an apprentice turner in a small factory. Mother sewed on another yellow star onto my overalls, we found a canvas satchel to hang across my left shoulder to carry my lunch in and I was ready to become a turner. My job on the first day was to stand beside the lathe and watch the foreman turner turning and listen to his verbal diarrhea about matters concerning the bloody Jews.

Just before evening I was instructed to warm some water and pour it into a basin. My boss washed his hands and face and invited the other four working for him to do likewise. When they had all finished he spat into the water and advised me that the water was now mine to wash myself in. Instead of water I washed my hand in kerosene.

The next day was just as instructive and the water was being spat into just before it was my turn to wash myself.

The third day my boss didn't realise that I spat into the water before he washed himself in it. Just the same he delivered his spit before my turn came and thus I continued to use kerosene to clean my hand, which caused a severe case of dermatitis.

One evening as I returned from work I found Mother hysterical. Earlier that day two gendarmes came to collect Father and took him away to a small village, where he had "de-centralised" some of his agricultural machinery stock. In spite of the fact that the gendarmes assured Mother that he was not being arrested, the reputation of the fascist gendarmes was such that they struck terror in even the innocent.

After he had spent three days in a village lock up the gendarmes brought Father home. Without them he could not have traveled on a train.

He explained to us the reason for his problems. Many months ago the Ministry of Industries circularised all agricultural machinery manufacturers and importers and instructed them to store all important, difficult-to-replace components away from Budapest, to protect them from bombing raids. Father took lorry loads of ball bearings, plough shares and all sorts of other materials to several farms, and in one case stored some ball bearings in the disused cellars of a vineyard.

Everything was above board, but someone saw the lorry arrive, and remembered it after the German occupation, when people were encouraged to report anything which seemed secret, unpatriotic or strange. The gendarmes investigated, and deduced that they had unmasked a huge Judeo-capitalist-communist conspiracy and were in any case interested to visit Budapest, hence their taking of Father into custody. They were quite hostile when the magistrate accepted his explanation and refused to prosecute him.

However they must have received new advice and a few days later they returned, and this time they arrested Father and took him to the prison in the township of Eger. He was housed in solitary confinement, and it was only a couple of days after his arrival in prison that he could send a message to us as to his whereabouts. By that time I was spending money and engaging the help of non-Jewish connections in trying to find him and getting things moving to free him from jail and was working on how we can send him food.

Just as Father was arrested, the latest regulations prescribed that all Jewish businesses must be taken over by a non-Jewish business or person. Action had to be taken fast, because a number of Father's competitors had put themselves forward to the authorities as being the best people to take over Father's business, including its assets, all of it for nothing. I myself had discussions with 3 or 4 competitors, who came looking for Father, but found that he was in prison and an 18 year old boy is in charge. They seemed sympathetic, but really all they were interested in taking advantage of the situation.

I realised that I had to find somebody to take over Father's Company, who was on our side and could be trusted. Somebody suggested Peter Agocs, our erstwhile chauffeur, who was then a corporal in the Army. I contacted his wife, somehow we contacted him, and he came home on compassionate leave. I explained that I would like him to "take over" the firm and he agreed. The next thing was to get him out of the Army, and Father's kind patron General Gerloczy obliged by pulling the necessary strings. Next Agocs put in a bid to become the General Manager on behalf of the State of the firm of Kálmán József, which was successful as I gave him the money to bribe the person whose responsibility was to appoint the new Managing Directors of Jewish enterprises.

He came back into the office, sat down at Father's desk and told me that he was successful and he also told me that things would be different from now on and would I please keep out of the office in the future. This was somewhat disappointing, coming as it did from somebody who was supposed to have been in the Kálmán family's service most of his life and who knew the dire straits we were in, but we were used to that sort of disloyalty.

However, Agocs was more cunning than I gave him credit for. Later that day he appeared at our home, with some money for us and told me that he would do everything for us, but we must appear to be remote from the business, so as to keep him out of trouble. He kept his word and was a true friend throughout this period.

Just the same, having been thrown out of Father's office earlier that day without the opportunity to remove some valuables and money, which were hidden in the cellar of the office amongst some agricultural spare parts and not being absolutely sure of Agocs' loyalty next day, I sneaked out of our flat and ran all the way to the office.

It was dark on the streets, there was a blackout and it was in the middle of the curfew imposed on Jews. I did not wear the yellow star, and if I would have been stopped, I would have had no excuse. I got to the office and let myself in. There, in total darkness, I descended into the cellar by climbing through the lift well, found some of the valuables, but not the money, and returned back to our block of flats, where once more I hid them, this time tied onto the lid of the toilet cistern. Over the next few days I sold some, while the rest were picked up for safe keeping by some Gentile acquaintances.

If Father being a jailbird was not enough, one morning at 5 a.m. two policemen, armed with rifles with bayonets affixed, came for me and I too was arrested. Mother was out of her mind, and of course neither I nor the policemen knew why I had been arrested. We all thought that my arrest is connected with Father's "crime". I was taken to a police station and from there to the school where I was no longer allowed to continue being a schoolboy.

It turned out that I had been arrested because I did not attend the pre-Army youth training. I explained that because of my racial inferiority I was not a member of the youth army (levente, i.e. similar to the Hitler Youth organisation), and in any case I was a member of the Fire Brigade, which was a substitute. They agreed that bringing me in was a mistake, but did not release me until a few minutes before curfew. In the meantime, Mother packed my clothing, blankets, food, etc, went to the police station and finally traced me to the school, where I found the food that she brought me very welcome.

Being in the Fire Brigade was not particularly pleasant. We had to serve the same way as the professional firemen, except that we did not get the same equipment, and for us it was a side line. I spent lots of nights waiting for a good fire and some of the times my patience was rewarded. One night we were involved in putting out some fires after an air raid. It was quite dangerous, and while our face and body were guarded by clothing, being left out our ears were cooked in the heat.

We were also confronted with the victims of the air raid and while I always felt happy when Budapest was bombed, I could not help but be sorry for the dead and injured and in spite of my pleasure of being bombed I was frightened when the bombs were falling. Any action by any of the allies against the fascists was welcome by us, even if it endangered our lives. We were much rather at the receiving end than noticing no action at all.

The town of Eger, were Father was incarcerated, was some 150 km north of Budapest. My Father's connection with Eger was that he was the supplier of most if not all the machinery requirements of the huge farm owned by the Roman Catholic Bishopric, which was the single biggest industry of Eger. After a few days in prison, Father was able to send a message to the chief farm manager, who in turn advised the Bishop of the illustrious prisoner, albeit racially inferior, in the local prison.

The Bishop, who may or may not have met Father, but who must have been a man of compassion and courage, then arranged for their solicitor to visit the prison, and Father engaged this kind, old and rather sleepy gentleman to defend him concerning whatever crime he would be charged with. The Bishop also instructed his staff to ensure that Mr Kálmán received food from the kitchens of the local hotel.

With all this attention, the prison authorities realised that they had an important guest and while they could not move Father from his solitary cell, they gave him a day-time servant in the shape of a young gipsy, who happened to be in prison for armed robbery. They also allowed Agocs, when he arrived in his Army uniform, to visit Father and spend a day with him in his cell.

After a while the prosecutor started to ask questions, and the official written charges were formulated and given to him. They were quite simple, Father was accused of sabotage, because he had hidden ball bearings and other material required for Hungary's war production. His defense, that he was instructed to remove the materials was not accepted, because it referred to agricultural machinery parts only and in any case he did not report the location of the material he removed from Budapest, where it was endangered.

Sabotage in time of war carried the death penalty, and you did not have to be Jewish to get the rope in Hungary.

Back in Budapest, I was busy in trying to amass a lot of cash which we felt might be required for bribes. I knew that somewhere in the cellar of the office there was a large amount of money hidden, which I failed to find on an earlier expedition. I was worried to ask Peter Agocs to try and find it and bring it to me. However well he behaved towards us, - you never knew. Finally, one night after curfew, I sneaked out once again, and using our old keys, I "broke" into our business and having had a torch on me, found and "stole" our money, which then had to be re-hidden in the flat.

With the help of General Gerloczy an agreement was reached with the Prosecutor in Eger, that he would ask for a life sentence only. The cost of the bribe was to be an amount equivalent to approximately $3-4,000 at a time when the annual salary of that Prosecutor may have been all of $1,000. The problem was how to advise Father that the Prosecutor had been bribed and would co-operate.

The solicitor from Eger wrote to us putting our mind at rest as to Father's physical well-being, but could give us little hope as regards his chances of being acquitted. However, he assured us that he would do his best at the forthcoming preliminary hearing which should take place 5 weeks after his arrest. Father's solicitor did not know of General Gerloczy's arrangement with the prosecutor either. It was getting very complicated and very worrying.

We arranged for Agocs to visit Eger again, to tell Father about the arrangements and to take some good clothing to Father for his court appearance and to stay in the town during the court hearing, which was to last two days.

The day before the Court sat, the German Gestapo arrived at the prison and asked for all Jews to be handed over. The prison authorities did so, but advised Eichmann's Gestapo assistants to come back for Father later, as he could not be handed over to them until he had attended the court next day.

It was at this time that all Jews outside Budapest were first concentrated in the confined space of local Ghettos and then, as rail trucks became available, were deported to Auschwitz for gassing and the crematorium, or work and probable death by starvation. The Gestapo in Eger, with the active and enthusiastic help of the Hungarian gendarme and other authorities, came for the Jews in the prison to concentrate them in the Ghetto prior to loading them into the cattle trucks, which were ready to roll.

Had the court in Eger not required the appearance of Father next day, they would have taken him to in Auschwitz. Two days later they were not interested, for the transports had left and Messrs. Endre and Baky the organisers of the death transports were arranging the deportation of another town’s Jews.

Because of delays in reaching Eger, Peter Agocs could not visit Father before his court appearance, although his suit and shirt reached him. The message that the Prosecutor had been bought could not be passed on to him and he was brought into court believing that he was fighting for his life. During the hearing he decided that the kind old solicitor was too polite and mealy-mouthed for him, and so Father sacked him, took over his own defense and to the surprise of the solicitor, the prosecutor and himself, proved his innocence, so that the judge declared him not guilty of all charges and set him free.

His next problem was how to travel back to Budapest, especially because by the time he was released the last train left. He finds that he was not allowed to stay in a hotel overnight, because no Jew was allowed the privilege of being a hotel guest. In any case he was the only Jew in the town of Eger, all the others having been deported.

To overcome their dilemma, Father and Agocs returned to the prison, where the kindly prison warden allowed him to sleep in his old cell, and even placed a second bunk in there for Agocs. Next morning, Agocs, who travelled in his Army uniform brought him back to Budapest as his "prisoner". His return to his family after 5 weeks of solitary imprisonment was regarded as an absolute miracle. But then those days were full of miracles and it seemed that every day alive was another miracle.

The day after Father returned regulations were posted, calling up all Jews, including those who were part Jewish or converted, from 18 to 50 to join as members of the infamous Labour Battalions. I was to leave on 5th June and travel to Felsöhangony, a place near the Slovakian border.

With the help of my cousin Bözsi, whose husband was in Russia and thus was regarded an expert, I bought the equipment required to become a slave labourer. The place supplying such outfits was believed to be the Scout Shop and after waiting in a queue of hundreds, we left with sufficient camping gear to make an assault on Mount Everest.

The night before my leaving, Father, who was convinced that he would be re-arrested, came to my room, woke me and told me that he and Mother had a discussion in their room, and they had reached the conclusion that the best way out would be suicide. I was told that Mother has sufficient poison for all of us.

I sat up and refused to do it. I explained that at least one of us should come through it all, and there should be somebody to tell John what happened. Father was crying, but he was listening. I wanted his promise that they would not do it without me, come what may. He went back to Mother and I could hear them talking. Finally, he came back to my room and gave me their solemn promise. He sat on my bed until I fell asleep and we never again discussed this topic with each other, although other people have informed me that he told them about the night when I talked them out of our suicide pact.

Next day I had my last breakfast, then my last lunch. It was like the hours before execution. Finally, in the afternoon, it was time to get dressed. I put on my knickerbockers, steel studded boots, and my brand new camping attire. I checked once again to make sure that I had my photographs showing me with Admiral Horthy. They might come handy. I said my good byes to Mother, put on my huge rucksack which had my two blankets rolled on top of it. On my side hung a smaller side bag, and I had a small suitcase in each hand. The only thing I did not need to take was a hat. That would be the one of two items of equipment that my country would provide for me. A soldier's cap, with the Hungarian emblem removed from its peak and an armband, which will not be yellow, but white, to show that I am racially Jewish, but not of the Jewish faith. That is all the equipment I was to receive to go to war!

Father was planning to accompany me as far as the tram stop, so as to give me last minute instructions on how best to survive. I gave and received a final hug from my sobbing Mother and I left for hell knew what. Actually, hell came sooner than I had imagined. Loaded up like a mule, I stepped out on to the marble floor of the staircase outside the flat. My steel studs skidded and my feet went from under me. The huge weight of my rucksack brought me down backwards, and my head just about knocked the bricks out of the wall. However, it was only me who was knocked out cold for a few minutes.

When I come to I find my Mother crying even more, and being joined by Father. I went into a laughing fit or hysterics call it what you wish. I was reminded of the gipsy who on being taken to his execution on a Monday morning remarks that his week was starting all wrong.

Nursing a huge bump I boarded the tram for the station. It was full with my future comrades who were going to the same station. When we got there, it became obvious that the Allies have nothing to fear from a Hungarian Army, provided it was transported by train. It seemed that nobody in charge had worked out that the 20,000 or so men called to go to the same Army camp, would require more than one train. After spending 4 hours waiting, about 18,000 of us were told to go home and come back tomorrow.

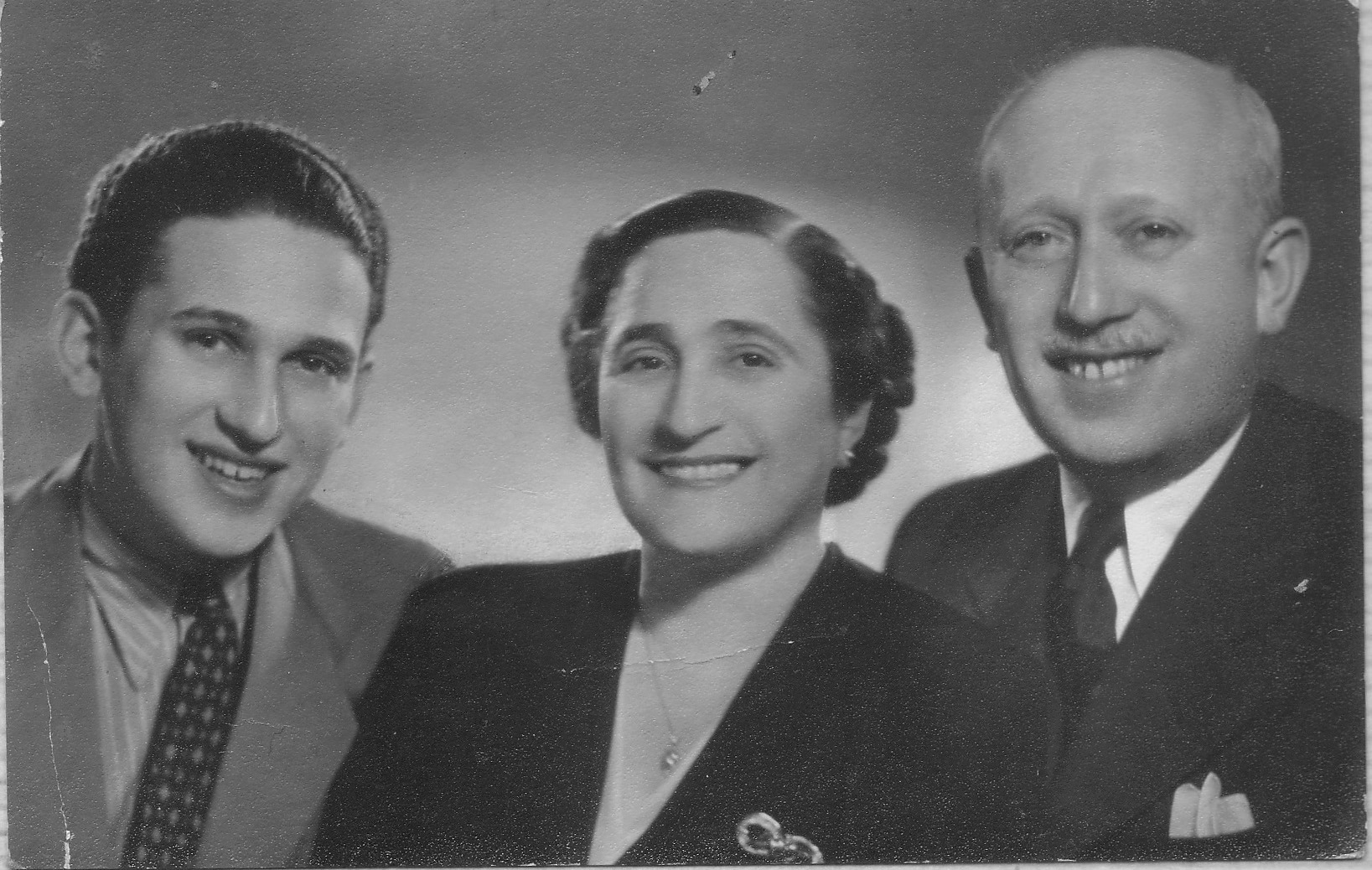

37 members of 711/101 Labour Company.

Only about 16 of these young people will survive the next six months.

(The writer is standing 5th from left.)

THE ARMY AND I

The train journey north was remarkable only in being a mobile rumour factory. It seemed that every body knew somebody who has heard something which was told to him by somebody who knew somebody who has heard it .... etc, etc. We traveled all night and most of the day to arrive to the steel making town of Ozd. From there we walked to our destination at Felsöhangony, a small village which formerly marked the border between Hungary and Czechoslovakia.

On our way we passed the boarded up windows of the ghetto houses in Ozd. From inside the locked up Jews shouted words of encouragement to us and we gave them news from the City. When we returned the same way some ten days later, the houses were empty, - the inhabitants having been taken to Auschwitz and were by then processed in the gas chambers.

As we approached Felsöhangony, we were met by the local gendarme, who were jeering at us while being pleased to see so many potential victims to make miserable and to fleece. They were not to be disappointed. In spite of us being under Army rule, the brave gendarmes could get their daily fun, by simply walking into the Army compound and kidnapping a few Jews to beat up and torture, just for fun. Their greatest pleasure was when they caught some of the wives, who traveled secretly to meet their men. Their screams could be heard throughout the nights. Next morning, with their broken spirits and beaten bodies, they were sent back to Budapest without having seen their husbands.

A few days after we left the place, some partisans arrived from the forests of Slovakia, set fire to the gendarme barracks and shot some 20 gendarmes. Luckily for us we were not there for their revenge.

The Army in comparison was much better to us. By the time we were made to join, most of the army personnel were middle aged remnants of the Great War and while they may not have loved the Jews, had less energy and imagination to torture us in the same fashion as the members of the Jewish labour battalions were tortured and destroyed in Russia in previous years.

In fact, the hardest time we had, whilst being trained in army drill, originated from fellow labour camp inmates, who have served 2, 3 or even 4 years in that capacity and who were charged to make "soldiers" out of us young city slickers. One of them, the young Jewish Österreicher was particularly hard on us. He made us sit on our heels until we fell over, made us run on the spot holding our rucksacks over our heads until our legs and arms were numb, shouted and swore at us and punished us heartlessly.

When in the cow sheds, where we slept, he became human, he told us that the only way we will survive if we become as strong and fit as he was. I believe that after the war, he became a General at the age of 25 and at 28 he was hanged during the show trials of 1949.

Our days consisted of being assembled, counted and drilled. Every now and then we marched about and often we were collectively punished, by having to jump around until fatigued or kneel in the middle of roads. It was quite an acceptable way to spend a day and we were not complaining. The food was quite acceptable, even if we had to wait in queues, but that was where we exchanged with our comrades our daily quota of war news and rumours. When evening came we bedded down in the various sheds or amongst cows in their stalls, where straw was made available for us to lie on and we all in turn did our guard duty and we made sure to be awake when our superiors arrived to check on the guards. One could hear the shout of the sentry challenging and than his report to those who went around to check on us. It could have been fun if it would have been on a boy scout jamboree, but we suspected that there might be a serious side to it all.

There was very little we contributed to the war effort, but it was early days yet. Soon whole companies were sent to help on farms to dig potatoes or cut timber. Having been instructed by my Father never to volunteer, I did not, when volunteers who could drive were asked for. A relation's future husband (Imre Nagy) put his hand up and was transferred to Budapest, where he spent the rest of the war, sleeping in his own bed every night.

My company was sent to a mine nearby and we replaced some of the miners, who were serving in the army and probably helping out on farms. The farmers were also in the army, but they were sent to act as guards to Jews, who were sent into the mines, etc. etc. No doubt similar inefficiencies were characterising other armies elsewhere, but the Hungarian Army could always be relied upon to be mind boggling.

We spent only a few days in the coal mines and were moved before we could be useful. We were not upset at being moved, although the German saying: "selten kommt was besseres nach" (seldom does something better follow) could not have been truer.

We were sent to the steel mills of Ozd. We marched through the streets and arrived to a school which was to be our home. We were looking forward to collapse on to our beds, which on this occasion, as was usual was to be the bare floor of the class rooms. However, we noticed that some dozens of gendarmes surrounded us and before we knew what is happening, all our possessions were checked. What they were looking for we did not know. They went through everything. The lining of some clothing was torn apart to check better. Cans of food had to be opened and checked. Pockets had to be emptied and the little money we had all disappeared. The belongings of 250 people were mixed up hopelessly by these laughing thugs, who after finding nothing in a shirt or pair of pants threw it on to a huge heap of other clothing, to be sorted out later.

This was the occasion when I "accidentally" showed my photographs of Admiral Horthy. The gendarme asked for an explanation, called in his superior, more arrived to see the photos and I was wondering if I will score my first beating of my Army career. Not at all, on the contrary, one of the Gendarmes started to pack my rucksack, while the other packed my hand luggage, my photos were handed back and a Gendarme helped my rucksack onto my back. Which just shows the mentality of these people and how easy it would have been for somebody in high places to control them instead of allowing them to terrorise us and the population at large.

We dropped on to our floor boards and soon found the least painful position to take up for a reasonable night's rest. It is not easy to sleep comfortably on bare boards, but we soon learned and surprisingly it was quite acceptable.

Next day we were off to become steel workers. Our job was to break up the steel that was poured into channels where it solidified. That steel was still extremely hot and to break it we had to use sledge hammers. To walk on the hot steel we wore wooden clogs covered by steel, but the wood used to catch fire. When that happened, we just had to hobble back to the sides of the area and douse the fire on our feet by whatever water there was.

We wore leather aprons and on our hands pieces of leather, so that we may carry the heavy, hot steel to the outside, where it had to be flung as far as will enable the steel to clear the platform we were standing on and fall into railway trucks below.

There was a way to do the job and the steel workers could have shown it to us. They preferred to have their amusement and taught us nothing. We were burned, dehydrated and endangered our lives. They worked two hour shifts, which was quite inhuman, we kids were given 8 hour straight shifts. They were each supplied 3 bottles of sweetened soda water per shift, we were allowed to drink as much as we liked out of the rubber hoses used to cool the steel. The fact that the water in these hoses was almost as hot as the steel, made our lives just that much more difficult.

It was obvious to every one, even the greatest of Jew-baiters that we could not give our best under these conditions, yet we were accused to sabotage our war and threatened with all types of dire consequences.

Luckily the place where the molten steel was cooling was of limited size and 250 of us could not work there all at the same time. This way, it was not difficult to be excused for health reasons and in any case, after a while, there was a roster in operation, which enabled us to go in on shorter shifts and even have days off. Just the same, injuries and burns were common place.

After about three weeks of this, one early morning we were marched down to the station and after we loaded up the horses, cooking utensils and a whole wagon load of black army bread, we also entrained into cattle trucks. The horses travelled 8 to the truck, 40 of us was to take up similar amount of space. It was July 8th. Our train contained my company and some other companies from our battalion. It was soon after we started to travel that we heard the news that there was an attempt at blowing up Hitler. It took two days for the news to get to us and even then some of us did not believe that it happened, some of us did not believe that he survived. Quite a number of us thought that if he dies things will deteriorate further. Many of us thought that Hitler is a calming influence on the "others" such as the SS, Gestapo, the Nazis.

I traveled in my railway truck in a sort of a haze. On my neck I had a number of carbuncles, some of which needed cutting open. The medical services in our company were provided by two medical students, who between the pair of them had almost 3 years of study, - some years ago. They took a knife, sterilised it by moving it over a flame and started to cut me open. I used a handkerchief for bandage and lay down on the floor of the cattle truck hoping to die or feel better, which ever comes first.

From the direction we were traveling it was obvious that we were going towards Russia. We were interested but fatalistically couldn't care less. What's the use, there was nothing we could do about it.

Back in Budapest some of the parents thought otherwise. They organised themselves into a quasi-committee and made enquiries any which way they could as to their sons whereabouts. Father was still friendly with General Gerloczy and it was he who finally located Company 711/101 on a train traveling towards Russia.

Father started to pull strings, while the locomotive pulling our train got us into Poland. It was definitely Poland as we fell asleep in our train, yet when we wakened we were in Hungary again. Interesting, where are we going from here? Our train next turned towards Romania, surely not that way? Next the train started to wander towards Budapest, then to the East again, then South. After 5 days the train turned North again and on the evening of our fifth day we stopped at the station of Kecskemét, some 150 kilometres south of Budapest. We arrived.

What we did not realise is that all the resources of the Hungarian Army and the Railways were used to trace the train containing Mr Kálmán's son and to turn it round away from the areas which did not show promise as places where the war can be weathered. The long trip was partly due to un-availability of locomotiv