SLEEPING AROUND

Going to Bed.

I decided to go to a cinema and afterwards, to boost my moral I had my boots cleaned by an old man outside the National Theatre. For want of something to talk about I asked him where he lived and he told me that he lives not far from there and is a "bed-goer". The only way to describe what a "bed-goer" is to say, that those people who were quite low down the scale and could not afford to rent a room or even share one, rented just a bed and thus were termed "bed-goers" i.e. they went to the place only to go to bed. There were bed-goers renting the bed during the night, while others rented the same bed during the day.

I asked the shoe cleaner if there were any vacancies where he rented a bed and he told me that he doubts it, but I should enquire. He asked me why I would want to bed-go, and I explained to him that my army pass only gives me a few days and of course I cannot afford anything better.

Off I went to the address he gave me and having told Mrs Szabó that I was on furlough from the front, the little fat old lady accepted me as suitable for one of her ten beds which were let by both day and night. Indeed, while we were talking in the kitchen I could see the room where the beds were and some of them were occupied. In total there were 12 beds, because both her and her son slept with the paying guests.

I paid her a deposit for my next nights' lodgings and went back to the timber yard to collect my belongings, then to another cinema, after which it was reasonable for me to arrive back at Mrs Szabó's place and bed down. I met some of my bed mates, the butcher from Transylvania being the most remarkable amongst them. There was also a young refugee couple, who paid for two beds but used one only and constantly. The street cleaner of shoes greeted me as a long lost friend, which gave me a status amongst these people. I can also remember a young apprentice who has lived with Mrs. Szabó for 4 years.

Another interesting person was one of those who rented a bed for day time sleeping and who told us one morning that she is a prostitute during the nights and therefore has to sleep during the day. The butcher was quite interested in a professional liaison with the young lady, and made an offer which was refused, with the excuse that if her pimp hears about her taking on clients during the day, she will be in trouble. The butcher thereupon offered her meat instead of money, but surprisingly this was also refused. I recognised the woman for what she really was: a Jewess whose cover story was the bit about being a pro. Heaven knows what her cover story was in another place where she must have spent her nights sleeping.

This was a period when everybody legitimate was prepared to tell their history, their adventures, their background and the butcher was no exception. So I heard where he came from originally, how he and his wife escaped from their Town in Transylvania, how they travelled until they got separated and how he got into Budapest. He told me how he went to the Refugee Registration Centre and how they sent him to the police station to register first and how he then had to return to the theatre where the Refugee Registration Office was set up.

I asked him all the questions I could, so that I became familiar with the sort of questions I may be asked and next morning I set out to get a set of absolutely genuine original false papers for my Mother.

My very first step was visiting a men's wear shop to purchase a walking stick, because for that day onwards I was to be a wounded soldier during the day, but unwounded when arriving as a bed-goer at Mrs. Szabó's place. In the course of the next 10 days or so, I had to hide my walking stick or throw it away and thus had to purchase several sets, always from the same shop. The shop assistant couldn't understand why I am buying all the walking sticks and finally asked me. In reply I told him that I work in a field hospital and I am buying this for my comrades.

My first trip with my stick was to a police station where I registered my Mother, as a refugee from the only Transylvanian town she ever visited, Nagyvárad. On my way to the station, I picked a house, memorised the number and street and this was to be where my Mother was supposed to live. I was more embarrassed than surprised when the policeman noticed the address and asked me whether my Mother rents a room from Mrs X or Mrs Y and of course I did not know if it is a trick question or what.

"Has she blond hair or black?" asked the man.

"I think it is blond," said I.

"Well, it is Mrs. Y than and you better tell your Mother to lock everything away, because she pinches everything that is not nailed down."

I got Mother's police registration and got the hell out of that police station as fast as I could.

Next stop was the Liszt Concert Theatre where long queues of refugees were waiting to be registered as refugees. Unless you had a full set of regular papers, without obtaining refugee status one could get no ration cards and what was more important, if you were registered as a refugee you could claim that you lost your documents and thus the need to have identity papers and papers to prove one's racial purity was alleviated. In fact there could have been no more complete documentation available to any Jew who went underground than a set of Refugee Identification papers.

To jump the queue I became the "Wounded Soldier" and due to my acting ability I was ushered past the crowds up the steps. My Mother's assumed name, Ilona Kálmán was showing little imagination on my part and it is typical that almost everybody who took false papers used his or her own name. There must be a psychological explanation for this.

The clerks interviewing the refugees were sitting at their trestle tables arranged according to the alphabet and thus I was interviewed by the man looking after names commencing with the letter "K". He soon gave me the almost priceless piece of paper proving that Mrs Kálmán is a refugee from Transylvania and my next aim was to hobble down the many steps of the Theatre and get past the real refugees, who were spending their days in badly organised queues for papers, rations, financial help, clothing and accommodation and therefore less than kind to people who jumped queues.

After the nervous strain of getting past the police, the refugee authorities and the refugees, getting the ration cards from the Food Office was easy. My next problem was where Mother could stay with her newly won refugee status and how to get her out and away from the Swiss House.

I cannot now remember, how it came about that I met Zsuzska Reszeli. She must have been somebody's maid or cleaning woman, and somebody must have suggested to me that I speak to her. I remember sitting with Mrs Reszeli and her daughter Csöpi and discussing my Mother who was a refugee from Transylvania. I knew that this was not true and so did they, we were going through an elaborate ritual of trying not to endanger their life.

Csöpi was 18 and she was a "little person". Her height was that of a 3 year old, her head may have been large for her body, she was not a true "Lilliputian" whose every feature was a scaled down version. Thus Csöpi was not very attractive to look at, but as soon as she opened her mouth and started to talk her gentle nature, her uneducated intelligence and her interest in everything around her, gave her an aura which made everybody to like her on sight.

They did not ask too many questions and there was no interest in discussing money matters. It was obvious that my Mother will pay for her keep and it was clear that if my Mother needed a home they will gladly provide it in their two roomed flat in the centre of Budapest.

I could not send any messages to Mother and had to get in the "International" Ghetto compound to bring her out. I went to reconnoitre and found guards at every entrance. I was devoid of ideas on how to get in there and even less ideas on how I could get out should I succeed in getting in. I left without attempting anything stupid.

Late afternoon and in the semi-darkness of late autumn I got back to see if I could get into the Ghetto. The situation was not different and there were guards to be seen at every street corner, where obstructions were acting as gates. I noticed one area where a "gate" was not manned. I was through that gate like a shot and once inside the Ghetto I started to run. I heard shouting but I was not likely to stop and argue with an armed Nazi guard.

I did not know which house Mother was in and had to take pot luck of running into the house most likely to be the correct one. The gate of the multi story building was open and beyond it a milling crowd who were surprised and terrified to see a soldier rushing in and running up the steps. I enquired what number that house was and found that I was in the right house. I rang the bell at the door of a flat and it was opened by one of Hungary's best known comedians, Dénes Oszkár, then married to George Schusztek's future wife, Bársony Rózsi, who was even more famous than her husband. He did not know Mother, but was not going to give me more information than was absolutely necessary, after all he also must have thought that I am a Nazi myself. He certainly looked scarred stiff. In the background I had a glimpse of the actress hiding around the corner of the entrance hall. (Years later, meeting her in Vienna she remembered, how I scared her.)

I continued my search and finally found Mother in an overcrowded flat on one of the upper floors. I undressed in a hurry and got myself into a bed on the floor, hiding my clothing under the mattress. It was from there that I watched the Arrow Cross guards who came in soon after, looking for the soldier who was observed to run into the house.

The guards left and Mother and I were without many ideas of what to do next. Finally, I realised that in spite of the terror of being frightened into total inactivity something has to be done whatever the risks, so I dressed, got Mother to put her bundle on her shoulder and quite openly and with considerable noise I escorted her out of the house and towards a gate different from the one I sneaked through.

I was asked where I was going and I said that I am taking the old bitch to headquarters for interrogation. Mother sniffled as if she would be petrified, which of course she was. We were allowed to go and we went our way. After a walk of 20 -25 minutes we arrived at the house where on the third floor the Reszeli's lived. It was very late at night, but they let us in and made us welcome.

I stayed with Mother overnight and it was on this occasion that I almost kicked her out of the window. My riding boots were quite tight for me and it was almost impossible for me take them off on my own. There is an old established way of pulling off boots and part of the exercise is for the person pulling the boot to hold the boot between the knees while being pushed away with the other foot. Mother's hands slipped as I was pushing her behind and she went flying with her head towards the low window. I dived after her and we collapsed in a heap, laughing until our laugh turned into crying.

In the mean time I was searching for a place for Father who had to move from the Baskay's place. Once again I cannot remember who suggested it, but I was given the name and address of a Jewish lady, who has taken refuge with one of her girl friends. I went to see them, but they already had someone else, a Jewess who spent years in prison as an active Communist, to come and live with them. However, the Gentile lady suggested that she might make some enquiries from her next door neighbour who ran an unregistered brothel in the flat next door. After a few minutes she came back and I was introduced to Frau Eidam, an Austrian lady of about 62 years, tall, well dressed and speaking atrocious Hungarian. In a few minutes she accepted my Father as a lodger and showed me the empty maid's room where Father was to live.

The next problem was Father's cover story. I decided that the refugee lurk might be the easiest to arrange. So I went through the performance again, first a visit to the police, then back to the Refugee Registration, where I faced the problem of being recognised of having been there earlier. I was lucky, I had no problems, in spite of the fact that for Father's papers I had to go to the same desk as before. Nevertheless, when obtaining his Food Ration Cards I visited a different Food Office to the one which issued Mother's coupons.

I contacted Baskay and we arranged to meet near the Royal Palace. Father and Baskay were already there when I arrived and were quite nervous. The area was full of German soldiers, SS and Army officers with Arrow Cross armbands. I was nervous also, but cheeky enough to greet every German with a very correct Heil Hitler. Baskay was impressed, but Father was not and the German soldiers probably thought that I am a bloody Nazi, but returned my greetings with a simple salute.

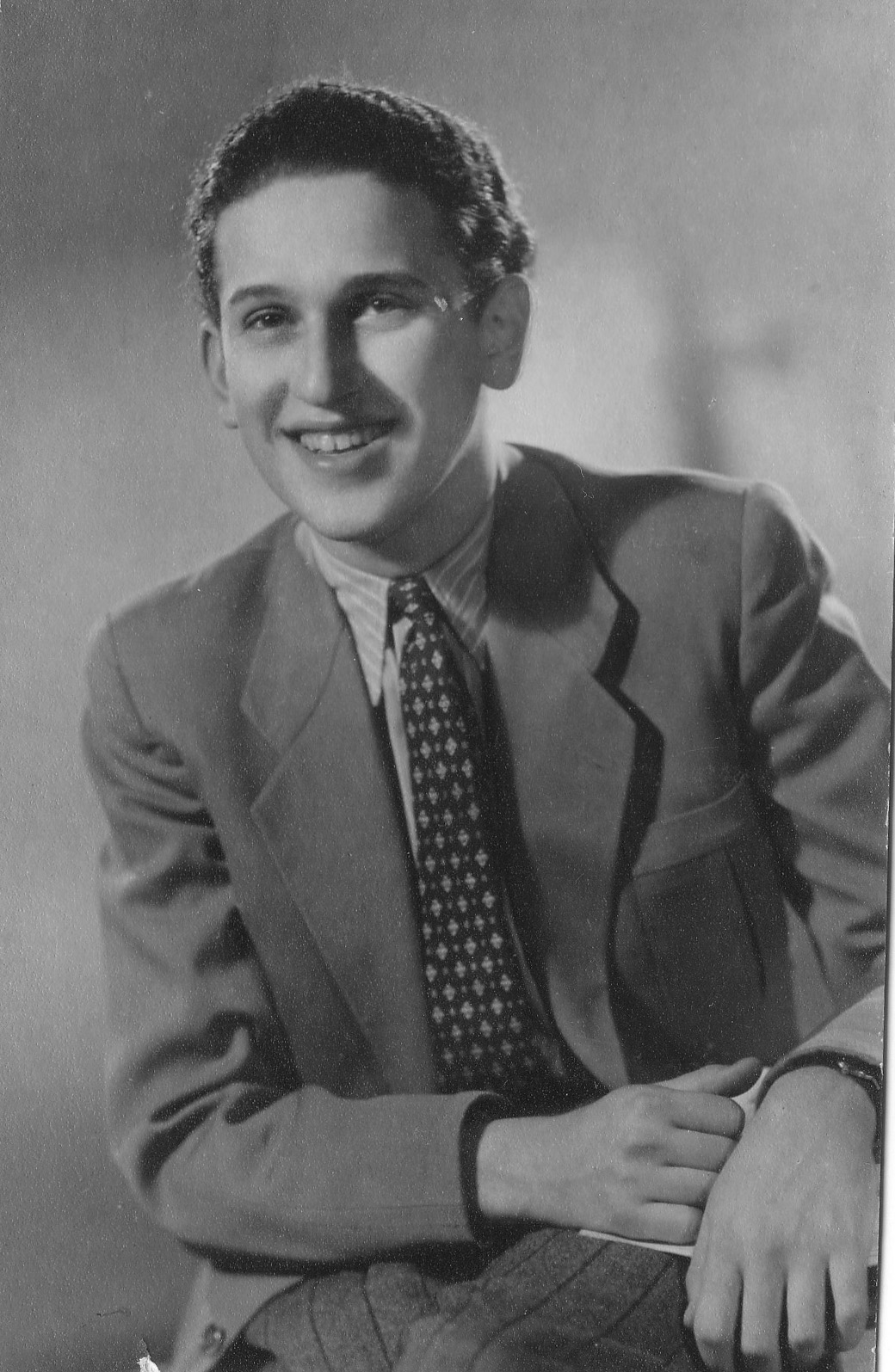

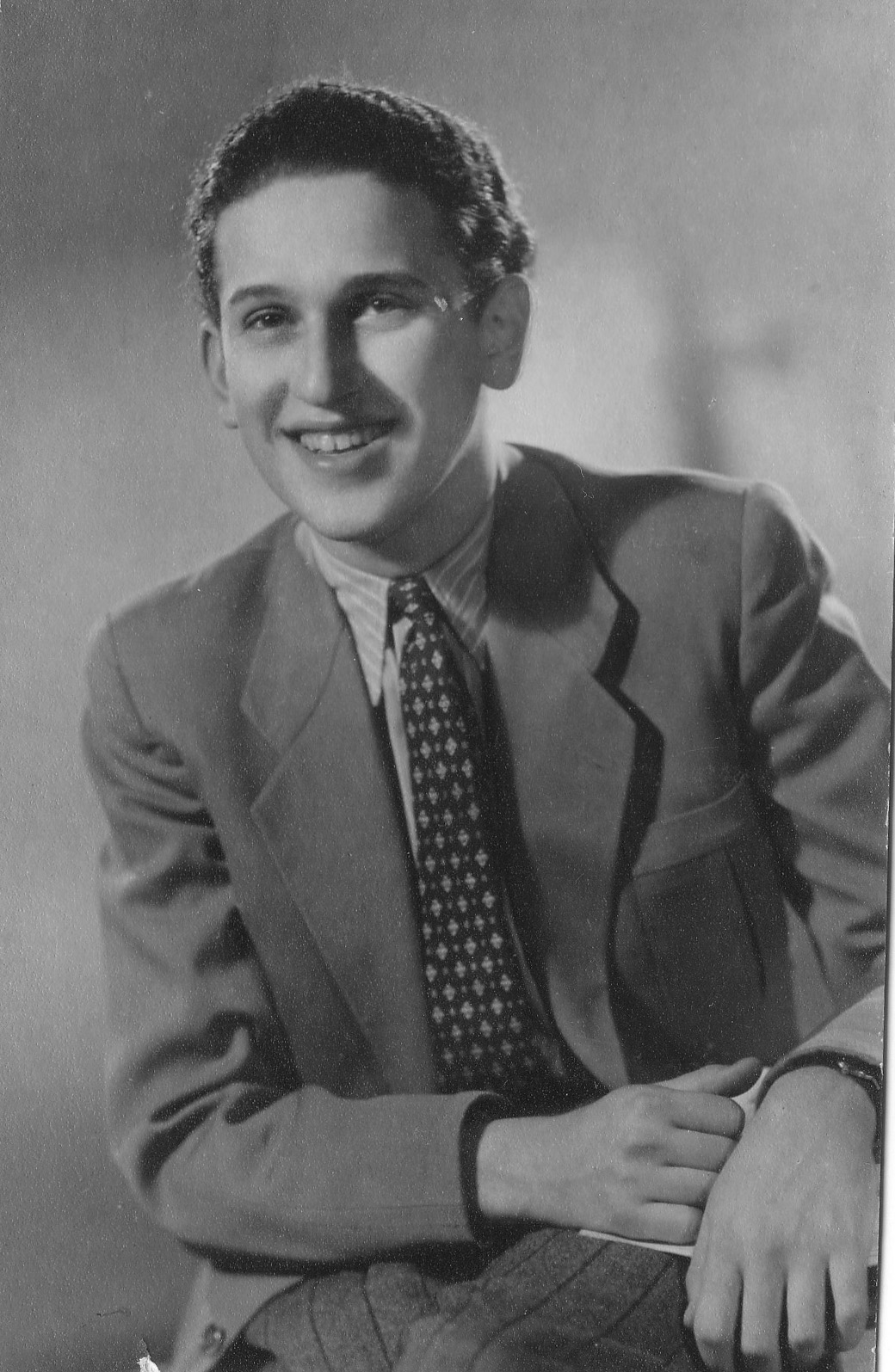

I am convinced that if sometimes I would have been less cheeky I would have been less successful. But recalling those days and my behaviour it was not cheekiness or courage but stupidity and enormous luck, which allowed me to survive. I cannot claim not to look Jewish and although I think that my curly black hair seemed to have become less curly during the time of my escapades, it is almost a miracle that no one got wiser to my subterfuge.

Let’s face it: I do look Jewish. It could have easily cost me my life.