CHAPTER I.

CONDITIONS IN ENGLAND

CAN we picture to ourselves the world in which Tindale gradually came into public view, made his voice heard in palaces, manor houses and homes of the common people; making enemies rage, but winning friends innumerable, until finally a price was set on his head: and there were Englishmen eager to entrap him to his death?

What was the condition of England then? What figures stand out conspicuous in the life of the nation? In whose hands did administrative power lie? In what directions were events moving? In the forefront of the nation strode Wolsey, clothed with power, dominating every avenue of corporate action, the master of church and state, and irresistible so long as he could retain the indulgence of the king. It was the time when Wolsey had succeeded in substituting royal despotism for quasi-representative government, and had himself risen to giddy heights of power and affluence, only to fall headlong in infamy and remorse. His sovereign had at length turned with Tudor frenzy against his minister. The king's marriage projects, his impatience with the Cardinal's vanity, as extravagant as it was grotesque, were not the only cause for dishonor; the King had purposes which called for servants of another type, and Henry was resolved to wield the royal power alone.

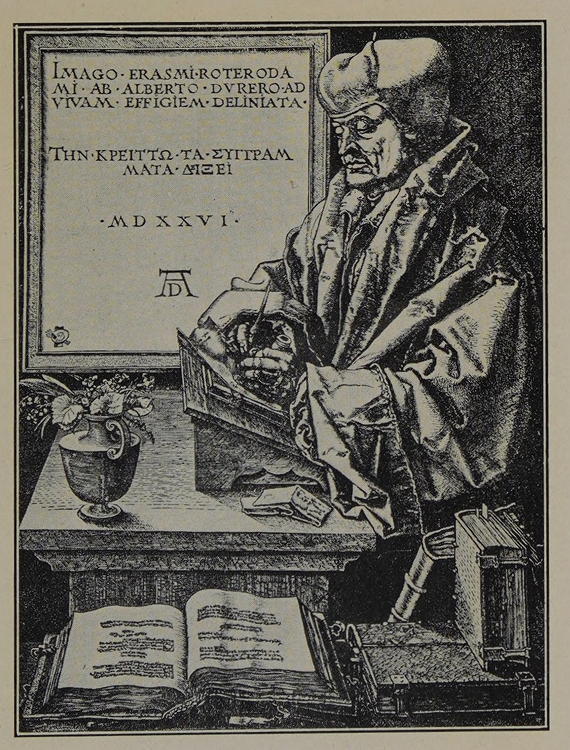

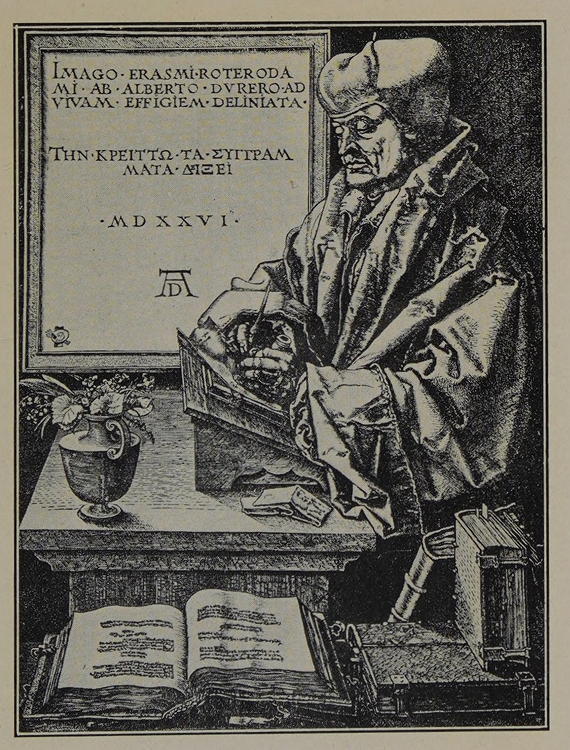

DESIDERIUS ERASMUS.

After Albert Durer.

Erasmus, More and Colet were the men of letters conspicuous in ability and influence during Tindale's boyhood. The three men were in intimate sympathy with one another; and each in his own fashion, exponents of the new learning, gave the country whole-hearted service. All were men of outstanding talent, and labored unceasingly for the ends they had in view. Colet was the preacher of renown. His University lectures on St. Paul's Epistles were scarcely less notable than his sermons in London. Sir Thomas More was witty, intense, versatile, broad-minded, gifted with imagination and courage; but when he encountered the violence of Luther suddenly changed to the recusancy of the bigots and the bishops. Erasmus, the greatest of the three, never altered his plans. He held on his way alike in all weathers undeterred, enlightening his time with the treasures he had found in the New Testament. It was in the year 1516 he issued his Greek Testament, with a Latin version alongside, correcting errors in the Vulgate; and that issue was a landmark in the history of the whole of Europe.

These three men incensed the conservatism of the Church. They refused to shut their eyes to the prevalent ignorance and unworthiness of the priesthood. They laid bare the open sores in the body ecclesiastic. Their irony and satire played about abbots, bishops and curés; but in all the castigation inflicted, there was no sign given by the priesthood of change or desire for reformation; only rancour and rage. As the truth got utterance given to it, the people took sides slowly, and the tides of feeling rose and spread. Listen to one voice from the multitude:

Men hurt their souls,

Alas! for Goddes will;

Why sit ye Prelates still

And suffer all this ill?

Ye Bishops of estates

Should open broad the gates

Of your spiritual charge

And come forth at large

Like lanterns of light

In the peoples' sight

In pulpits awtentike

For the weal publyke

Of priesthood in this case.

—John Skelton.

Gloucestershire was a stronghold of the Church. The proverb "As sure as God is in Gloucester" gave point to it. Only a few of the clergy understood the Latin services they read or sang. None of them knew the contents of the Bible; and many were outspoken in their disparagement of it. When argument arose and some rare voice made reference to the Bible, they thought to silence him by saying the Pope, or this or that, was above the Bible. It was in the course of conversation and debate that a certain man ejaculated to Tindale "We were better be without God's laws than the Pope's". The attitude is the more to be remarked because as a consequence of the new learning there had been a wide diffusion of the Bible in the Latin language (the Vulgate) since the invention of printing. No fewer than eighty editions, although one cannot ascertain what was the size of the editions, had been issued between 1462 and 1500.

As a sign of the times, this diffusion of the Latin Bible was curiously significant. Significant it was indeed in more ways than one. It showed (1) that the scholars of the church were being influenced by the new learning; but also (2) that a strict reservation was to be enforced in confining it to scholars. The Bible was for scholars, not for others. A fine instance is in the case of the Complutensian Polyglot. Complutum was the Latin name of Alcala. In 1502 Cardinal Ximenes, the founder of Alcala University, decided on the issue of a Polyglot edition of the Bible wherein the Vulgate should be placed alongside of the best Hebrew and the best Greek manuscripts. "Every theologian", he said, "should also be able to drink of that water which springeth up to eternal life at the fountain head itself.... Our object is to revive the hitherto dormant study of the Sacred Scriptures". The very men who thus engaged in the publication of the Bible, denounced with the direst of penalties its distribution outside the charmed circle of the learned.

Freedom of conscience there was none. Tolerance was proclaimed as an emanation of Hell. Difference of opinion was deadly. To acknowledge misgiving or doubt or dissent was incontinently to be rated as a rebel and exposed to the truculency of a pitiless hierarchy.

There is a companion picture of the English world at that time, lurid and indeed sickening. The bishops sank their humanity in frenzied partisanship, gave rein to cruel and monstrous passion, aided and abetted therein by More as Lord Chancellor. They lit the fires of Smithfield, and the spectacle of Englishmen perishing at the stake for honesty of thought and sincerity of life, became so familiar as to case-harden the people at the scenes. One story, typical of scores of others, may be given.

The story has reference to Bainham's execution: "Among the lay officials present at the stake, was 'one Pavier', town clerk of London. This Pavier was a Catholic fanatic, and as the flames were about to be kindled he burst out into violent and abusive language. The fire blazed up, and the dying sufferer, as the red flickering tongues licked the flesh from off his bones, turned to him and said, 'May God forgive thee and shew more mercy than thou, angry reviler, shewest to me.' The scene was soon over: the town clerk went home. A week after, one morning when his wife had gone to mass, he sent all his servants out of the house on one pretext or another, a single girl only being left, and he withdrew to a garret at the top of the house, which he used as an oratory. A large crucifix was on the wall; and the girl, having some question to ask, went to the room, and found him standing before it, 'bitterly weeping'. He told her to take his sword, which was rusty, and clean it. She went away and left him; when she returned, a little time after, he was hanging from a beam, dead. He was a singular person. Edward Hall, the historian, knew him, and had heard him say, that, 'if the king put forth the New Testament in English, he would not live to bear it.' And yet he could not bear to see a heretic die. What was it? Had the meaning of that awful figure hanging on the torturing cross suddenly revealed itself? Had some inner voice asked him whether, in the prayer for his persecutors with which Christ had parted out of life, there might be some affinity with words which had lately sounded in his own ears? God, into whose hands he threw himself, self-condemned in his wretchedness, only knows the agony of that hour. Let the secret rest where it lies, and let us be thankful for ourselves that we live in a changed world."

(Froude, Henry VIII.)

When the mind pauses to reflect on this doing to death of men because their faith did not square with that of those in high places, and succeeds in freeing itself from the numbing influence which its very familiarity causes, the amazement and horror of the practice help us to measure the criminal folly of it. One must make an effort indeed to shake off that deadening influence; and then, and only then, the arrogance and impiety of claiming injustice, torture, judicial murder, as a service to God, make one shudder as at blasphemy. Yet what awful pages of history in every part of Christendom record the deeds of this sanguinary orthodoxy. How hard has mankind found it to learn that persuasion and forbearance are the real solvents of dissent; for the faith in force is hardly shaken to this day. Forcible suppression is in high favor still. It may not, dare not, perhaps, work by the same crude and sanguinary tools, although the disclosures of the Great War, or of Soviet Russia, may give the lie to that caveat: but little observation is needed to show how in subtler forms, alike in politics and in religion, there is the same impatience with disagreeing opinion, and the same self-assurance that does not hesitate to silence a disputant by death or shame. Wherever it lifts its head, it is the head of Anti-Christ.