CHAPTER VI.

IN EXILE: (2) TRANSLATING THE NEW TESTAMENT

TINDALE'S life upon the Continent of Europe can be traced in no more than broken outline. Gaps of space and time are frequent; for, as already indicated, whatever letters or other documents there may have been have long ago disappeared, and we have little more than knowledge of extended residence at certain important points, Hamburg, Cologne, Worms, and shorter visits to the Wartburg, Wittenberg, Antwerp, etc. As Froude aptly says: "His history is the history of his work, and his epitaph is the Reformation."

It was in Worms that the famous diet had been held at which Luther braved the Empire in its assembled might, and here it is that Rietschel's monument to the Reformation stands in bronze and granite. Colossal figures, Waldo and Wyclif, Huss and Savonarola, have towering above them the figure of Luther, his right hand clenched and resting on the Bible. Bas-reliefs and medallions carry select details. Where selection was imperative, there could not fail to be regrettable omissions; but one misses also forces that were vital. Gutenberg is not there; nor any symbol of his craft.

Without the service rendered by the printing press of recent invention, it is almost inconceivable that there could have been any such world-shaking event as the Reformation proved. Not only was the burning eloquence of the preacher carried by this means far and wide, but the Scriptures themselves in the language of the people were thrown off from scores of presses in the Rhine Valley and dispersed to many lands. Like wildfire knowledge ran.

Gutenberg, and Fust with Schoeffer in Maintz, Quentel and Bryckmann in Cologne, were the names most frequent on the title pages of the Bible; and their fame has proved enduring.

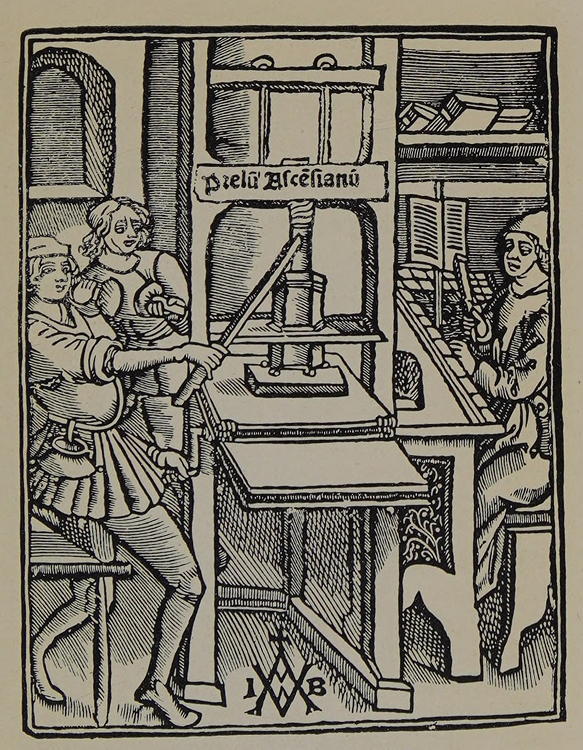

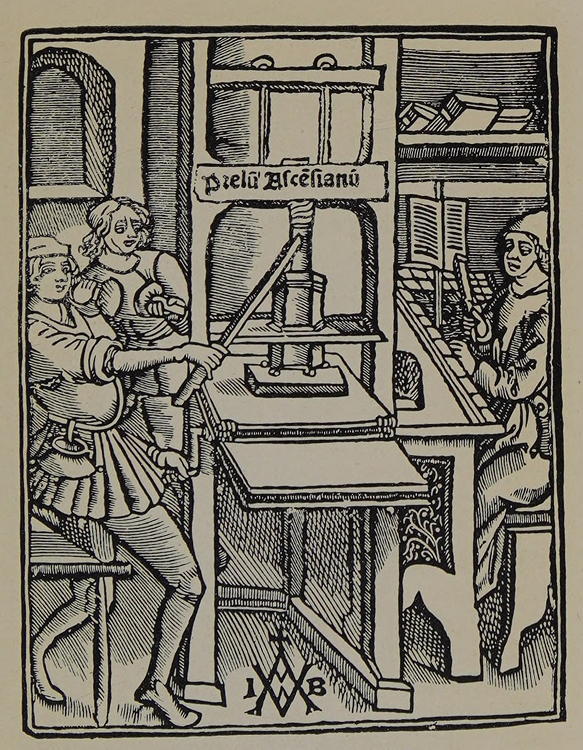

PRINTING PRESS, 1511.

Title page of "Hegesippus", printed by Jodocus Badius Ascensius, Paris, 1511.

In the early decades of the Sixteenth Century, even in Germany printing was still regarded as one of the marvels of the time. But in England, the first quarter of the century had just ended when the authorities took alarm at its power and sought to curb it. They instituted a censorship to kill it. Its development was persistently thwarted for many years.

Well did Tindale understand that the English government not merely forbade the translation of the Bible into the native tongue, but were trying to strangle the printing craft in its infancy.

Out of England the trade was prospering at many centres.

He landed at Hamburg. Even then the city was a busy commercial centre with business and shipping interests linking it with every part of the commercial world. Among the inhabitants were men who welcomed Tindale and who gave him assistance in various ways. But he was soon aware that for his work one essential was lacking. Not a single printing press had been set up in Hamburg as yet. His acquaintance with Hamburg, however, was of enduring value. The friends he made there he retained, and later visits were a solace and encouragement in days when friends were friends indeed.

He proceeded to Cologne, where there was every facility for printing. He had the first parts of the New Testament in 4to. ready for the press. Enemies, however, were around and alert. Circumspection and secrecy were essential. The work progressed. The printer had got as far as the first ten sheets when a restless and resolute enemy, Cochlaeus, having ferreted the secret from one of the workmen in his cups, obtained authority to put a stop to the work. Tindale managed to secure his property and left the city. He escaped up the Rhine to safety in the city of Worms; where reformation was in power, and where he could continue his work with new feelings of security.

Here, then, he lost no time in resuming his work.

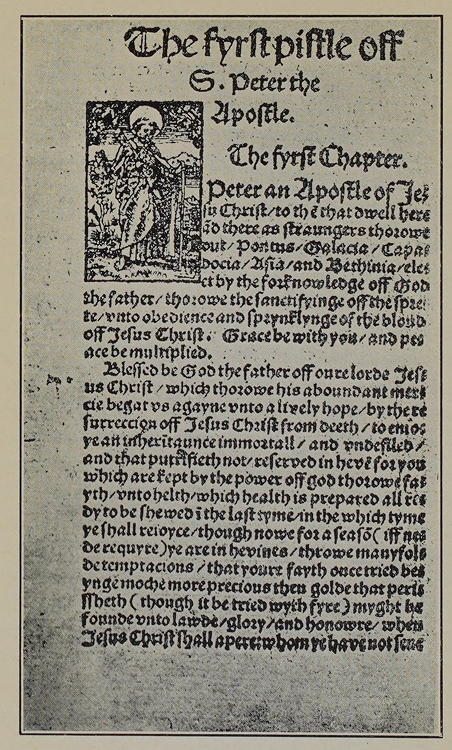

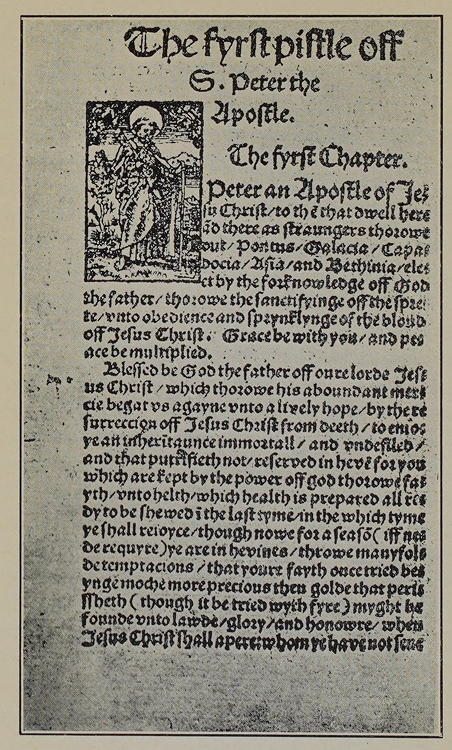

PAGE OF 1525 OCTAVO.

New Testament.

He found a sympathetic printer in P. Schoeffer. Tindale appears to have rearranged his plans. Possibly he had ascertained that Cochlaeus, balked of victory at the very last, had with vindictive cunning sent letters to England giving full particulars of the kind of volume that was in the making: (It was to be a 4to. with notes and comments) and urging the authorities to guard against its being smuggled into the country. Tindale forestalled that enemy. It was not a 4to. volume which he now designed at Worms, but an 8vo. volume; and this had neither note nor gloss. It would seem that alongside of this, but at more leisurely pace, the 4to. also was completed, very likely in the same printing house. Both volumes bear the stamp of the same year of issue, 1525. The two editions were successfully conveyed to England; so that the immediate effect of the attack was to issue two editions instead of one—6,000 volumes instead of 3,000. A skilful system of Colportage carried these books all over England. Before the books arrived, the King had a second warning. Edward Lee, afterwards Archbishop of York, was then on the Continent, and dating his letter from Bordeaux, December 2nd, 1525, he says: "Please it Your Highness to understand that I am certainly informed as I passed in this country that an Englishman, your subject, at the solicitation and instance of Luther with whom he is, hath translated the New Testament into English, and within a few days intendeth to arrive with the same imprinted in England. I need not to advertize Your Grace what infection and danger may ensue hereby if he be not withstanded. This is the next way to fulfil your realm with Lutherians." Then he adds: "All our forefathers, Governors of the Church of England, hath with all diligence, forbid and eschewed publication of English Bibles, as appeareth in Constitutions Provincial of the Church of England."

The news had travelled far before reaching Lee, and was inaccurate at that: but the swiftness with which it reached him was proof of the excitement which Cochlaeus' discovery had created.

More interesting and more accurate is a notice which occurs in the diary of a German scholar,[2] some four months earlier in time. He says: "One told us at the dinner table that 6,000 copies of the English Testament had been printed at Worms: that it was translated by an Englishman who lived there with two of his countrymen. He was so complete a master of seven languages—Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Italian, Spanish, English and French—that you would fancy whichever one he spoke was his mother tongue." He adds that the English, in spite of the opposition of the King, were so eager for the Gospel, as to affirm they would buy a New Testament even if they had to give a hundred thousand pieces of money for it.

While the enemy raged, the presses abroad were not idle. Additional editions were printed to take the place of those destroyed. They were conveyed with the same success to English ports. In less than five years six editions had been published, three of them surreptitiously. They numbered perhaps fifteen thousand copies in all, and were distributed to eager purchasers by the same formidable organization of colportage.

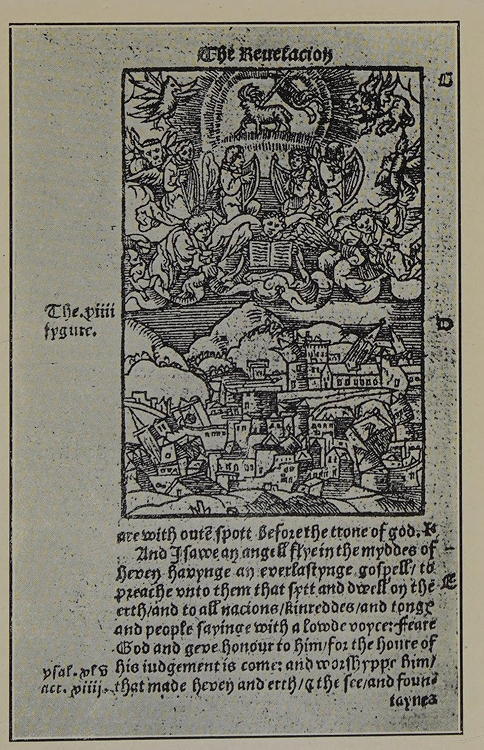

Nor was Tindale idle. He had foreseen the tactics of his foes. He kept steadfastly at work. He revised his translation of the New Testament, and he proceeded to turn the Old Testament into the English speech; the Pentateuch, the historical books as far as Chronicles, the book of Jonah he completed. In 1536 he was able to send the manuscript of his revised New Testament to England, and there it was put upon the press. That was the first volume of Holy Scripture to be printed on English soil.

It was, however, the closing year of Tindale's life. Before the book came off the press he may have sealed his testimony; but at least he would be cheered by tidings of its progress, and the knowledge that the work had found its proper home in his own land. "For this end", says Westcott, "he had constantly striven; for this he had been prepared to sacrifice everything else; and the end was gained only when he was called to die."

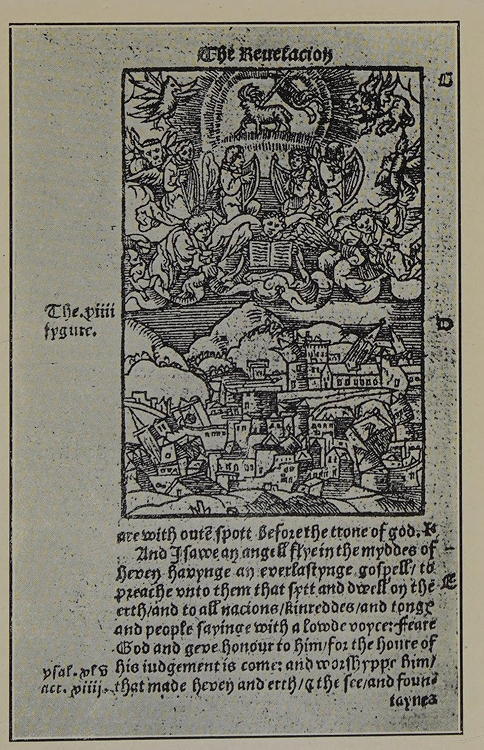

PAGE FROM TINDALE'S 1536 REVISED NEW TESTAMENT.

Some time elapsed before the discovery of the contraband Testament was made by the ecclesiastical authorities, who then instituted a search so bitterly persistent and so pervasive in its continuance, that, of these editions, there survive in our time only a couple of 8vo. copies, one of these incomplete; and only a fragmentary copy of the 4to. The eventual destruction, however, did not prevent the Testament meanwhile having its own influence and bringing comfort and hope to thousands of English homes.

Not only so,—and this is the tribute that is due to Tindale's translation,—the translation as Tindale made it is in substance and form the English New Testament as we have it to-day. Notwithstanding the numberless revisions that have taken place, it is substantially Tindale's translation still; for the revisers have always, unconsciously perhaps, done their revising in the spirit and manner of Tindale. Of all that have worked upon the English Bible, no other single man has left his mark on this book; the version in our hands to-day bears the unmistakable stamp of its first translator.

"The peculiar genius—if such a word may be permitted—which breathes through it—the mingled tenderness and majesty—the Saxon simplicity—the preternatural grandeur—unequalled, unapproached, in the attempted improvements of modern scholars,—all are here, and bear the impress of the mind of one man—William Tindale. Lying, while engaged in that great office, under the shadow of death, the sword above his head and ready at any moment to fall, he worked, under circumstances alone perhaps truly worthy of the task which was laid upon him,—his spirit, as it were divorced from the world, moved in a purer element than common air."

(Froude, Henry Eighth, Vol. II).

The contents of this book as it passed into the hands of the nation, printed not in the language of the court, nor in that of either the statesman or the scholar, but in the language of the common people, finding them, as it did, more especially at critical times when events seemed to be threatening the overthrow of the nation as much as of the individual, stole into the imagination of the people, and by degrees gave form and life to those great virtues, justice, freedom, truth, tolerance and self-sacrifice, which have become the vivid traditions that govern in the main the English-speaking people. Here was the fountain head from which the main stream of their literature, legislation, public policy, and national character derives its flow and power.

For it is admitted that the distinction of this great people from other nations in a certain generosity, patience, integrity and courage, rests remotely on their silent appropriation of the vital forces released in this book of God.

Such far-reaching consequences afford the best measure of the immense significance—much greater than he could foresee—of Tindale's toil that he might open the eyes of England to the message he succeeded in turning into imperishable language under-standed of the people.

No phase of Tindale's work intrigues the student so much as his perfect command of his native tongue. Where and how did he acquire this mastery of pure sonorous English, whose rhythmic prose is like stately music to the most cultured ear? Study of the Vulgate and of the originals he worked on has not indeed to be overlooked as a possible source; but there is a gift, native-born, or acquired in secret toil, which, with those tides of devout feeling we find swelling in the man himself, stamps the style as the organ utterance of his consecrated manhood.

Tindale's rendering of 1 Cor. 13, with the parallels for comparison of Wyclif and the Authorized Version of 1611, illustrates both the style of the great translator and the permanence of his translation in the version current for four hundred years.

WYCLIF—1380

If I speke with tungis of men and of aungels, and I haue not charite, I am made as bras sownynge or a cymbal tinkynge, and if I haue profecie, and knowe alle mysteries, and al kynnynge, and if I haue al feith so that I meue hillis fro her place and I haue not charite I am nouzt, and if I departe alle my godis in to metis of pore men, and if I bitake my bodi so that I brenne, and I haue not charite if profetith to me no thing, charite is pacient, it is benyngne.

charite enuyeth not, it doth not wickidli it is not blowun it is not coueitous, it sekith not the thingis that ben his owne, it is not stired to wraththe, it thenkith not yuel, it ioieth not on wickidnesse, but it ioieth to gidre to truthe, it suffrith alle thingis: it beleueth alle thingis, it hopith alle thingis it susteyneth alle thingis, charite fallith neuer doun, whether profecies schuln be voidid, ether langagis schulen cease: ether science schal be distried,

for aparti we knowen and aparti we profecien, but whanne that schal come that is perfizt, that thing that is of parti schal be avoidid, whanne I was a litil child, I thouzt as a litil child, but whanne I was made a man I voidid tho thingis that weren of a litil child, and we seen now bi a myrrour in derknesse: but thanne face to face, now I knowe of parti, but thanne I schal knowe as I am knowen, and now dwellen feith hope and charite these thre: but the moost of thes is charite.

TYNDALE—1536

Though I spake with the tonges of men and angels, and yet had no love, I were even as soundings brasse: or as a tynklynge Cymball. And though I coulde prophesy, and vnderstode all secretes, and all knowledge: yee, yf I had all fayth so that I coulde move mountayns oute of ther places, and yet had no love, I were nothynge. And though I bestowed all my gooddes to fede the poore, and though I gave my body even that I burned, and yet had no love, it profeteth me nothinge. Love suffreth longe, and is cirteous. Love envieth not. Love doth nor frowardly, swelleth not dealeth not dishonestly, seeketh not her awne is not provoked to anger, thynketh not evyll, reioyseth not in iniquite: but reioyseth in the trueth, suffreth all thynge, beleveth all thynges, hopeth all thynges, endureth in all thynges. Though that prophesyinge fayle, other tonges shall cease, or knowledge vanysshe awaye, yet love falleth never awaye.

For oure knowledge is vnparfect, and oure prophesyinge is vnperfect. But when that which is parfect is come, than that which is vnparfect shall be done awaye.

When I was a chylde, I spake as a chylde, I vnderstode as a chylde I ymagened as a chylde. But assone as I was a man, I put awaye childesshnes. Now we se in a glasse even in a darke speakynge: but then shall we se face to face. Now I knowe unparfectly: but then shall I knowe even as I am knowen. Now abideth fayth, hope, and love, even these thre: but the chief of these is love.

AUTHORIZED—1611

Though I speake with the tongues of men and of Angels, and haue not charity, I am become as sounding brasse or a tinkling cymbal. And though I haue the gift of prophesie, and vnderstand all mysteries and all knowledge: and though I haue all faith, so that I could remooue mountains, and haue no charitie, I am nothing. And though I bestowe all my goods to feede the poore, and though I giue my body to bee burned, and haue not charitie, it profiteth me nothing. Charitie suffereth long, and is kinde: charitie enuieth not: charitie vaunteth not it selfe, is not puffed vp, Doeth not behaue it selfe unseemly, seeketh not her owne, is not easily prouoked, thinketh no euill, Reioyceth not in iniquitie, but reioyceth in the trueth: Beareth all things, beleeueth all things, hopeth all things, endureth all things. Charitie neuer faileth: but whether there be prophesies, they shall faile; whether there bee tongues, they shall cease; whether there bee knowledge, it shall vanish away. For we know in part, and we prophesie in part. But when that which is perfect is come, then that which is in part, shall be done away. When I was a childe, I spake as a childe, I vnderstood as a childe, I thought as a childe: but when I became a man, I put away childish things. For now we see through a glasse darkely: but then face to face: now I know in part, but then shall I know euen as also I am knowen. And now abideth faith, hope, charitie, these three, but the greatest of these is charitie.

[2] Buschius (Herman von dem Busche).