VII

AFTER THE EVENT

THE Wrights felt a glow of pride and satisfaction in having both invented and demonstrated the device that had baffled the ablest scientists through the centuries. But still they did not expect to make their fortunes. True, they had applied, on March 23, 1903, or nearly nine months before they flew, for basic patents (not issued until May 22, 1906), but that was by way of establishing an authentic record. Thus far they hadn’t even employed a patent lawyer.

Long afterward, Orville Wright was asked what he and Wilbur would have taken for all their secrets of aviation, for all patent rights for the entire world, if someone had come along to talk terms just after those first flights. He wasn’t sure, but he had an idea that if they had received an offer of ten thousand dollars they might have accepted it.

Since the airplane was not yet developed into a type for practical use, ten thousand dollars might have been considered a fair return for their time, effort, and outlay. They had had all the fun and satisfaction and their expenses had been surprisingly small. Their cash outlay for building and flying their power plane was less than $1,000, and that included their railroad fares to and from Kitty Hawk. Of course, the greater part of their expenses would have been for mechanical labor, much of which they did themselves. But skilled labor was low-priced at that time; one could hire a better than average mechanic for as little as $16 a week. Even if the Wrights had charged themselves with the cost of their own work, their total expenses on the power plane would still have been less than $2,000.

Many fanciful stories have been told about the sacrifices the Wright family made to enable the brothers to fly, and of how they were financed by this person or that. More than one man of wealth in Dayton has encouraged the belief that he financed them. One persistent story is that they raised money for their experiments by the sale of an Iowa farm in which they had an interest. The truth is that this farm, which had been deeded by their father to the four Wright brothers, was sold early in 1902 before Wilbur and Orville had even begun work on their power plane or spent much on their experiments. The sale was made at the request of their brother Reuchlin, and had no relation whatsoever to aviation. Nor is it true that the Wright home was mortgaged during the time of the brothers’ experiments. Another story was that their sister Katharine had furnished the money they needed out of her salary as school teacher. Katharine Wright was always amused over that tale, for she was never a hoarder of money nor a financier, and could hardly have provided funds even if this had been necessary. Any rumor that her brothers could have borrowed money from her, rather than lending money to her, as they sometimes did, was almost as funny to Katharine as another report—that her brothers had relied on her for mathematical assistance in their calculations.

The simple fact is that no one ever financed the Wrights’ work except Wilbur and Orville themselves. Their bicycle business had been giving them a decent income and at the end of the year 1903 they still had a few thousand dollars’ savings in a local building and loan association. Whatever financial scrimping was necessary came after they had flown; after they knew they had made a great discovery.

But the Wrights’ belief that they had achieved something of great importance was not bolstered by the attitude of the general public. Not only were there no receptions, brass bands, or parades in their honor, but most people paid less attention to the history-making feat than if the “boys” had simply been on vacation and caught a big fish, or shot a bear.

Before the flights, some of the neighbors had been puzzled by reports that the Wrights were working on a flying-machine. One man in business near the Wright shop had become acquainted with an inventor who thought he was about to perfect a perpetual motion machine; and this businessman promptly sent the inventor to the Wrights, assuming that he would find them kindred spirits. John G. Feight, living next door to the Wright home, had remarked, just before the brothers went to Kitty Hawk: “Flying and perpetual motion will come at the same time.”

Now that flights had been made, neighbors didn’t doubt the truth of the reports—though one of them had his own explanation. Mr. Webbert, father of the man from whom the Wrights rented their shop, said:

“I have known those boys ever since they were small children, and if they say they flew I know they did; but I think there must be special conditions down in North Carolina that would enable them to fly by the power of a motor. There is only one thing that could lift a machine like that in this part of the country—spirit power.” Webbert was a spiritualist. He had seen tables and pianos lifted at séances!

But even if the boys had flown, what of it? Men were flying in Europe, weren’t they? Hadn’t Santos-Dumont flown some kind of self-propelled balloon?

The one person who had almost unbounded enthusiasm for what the brothers had accomplished was their father. They found it difficult to keep a complete file of the photographs they had made showing different phases of their experiments, because the moment their father’s eye fell on one of these pictures he would pick it up and mail it to some relative along with a letter telling with pride what the boys had done.

Two brothers in Boston sensed, however, that, if the scant reports about the Kitty Hawk event were based on truth, then something of great significance had happened. These men were Samuel and Godfrey Lowell Cabot, wealthy and influential members of a famous family. Both of them, particularly Samuel, had long been interested in whatever progress was being made in aeronautics. On December 19, the day after the first news of the flights was published, Samuel Cabot sent to the Wrights a telegram of congratulations. Two days later, his brother Godfrey wrote them a letter. In that letter Godfrey Cabot wanted to know if they thought their machine could be used for carrying freight. He was financially interested in an industrial operation in West Virginia, he said, where conditions would justify a rate of $10 a ton for transporting goods by air only sixteen miles.

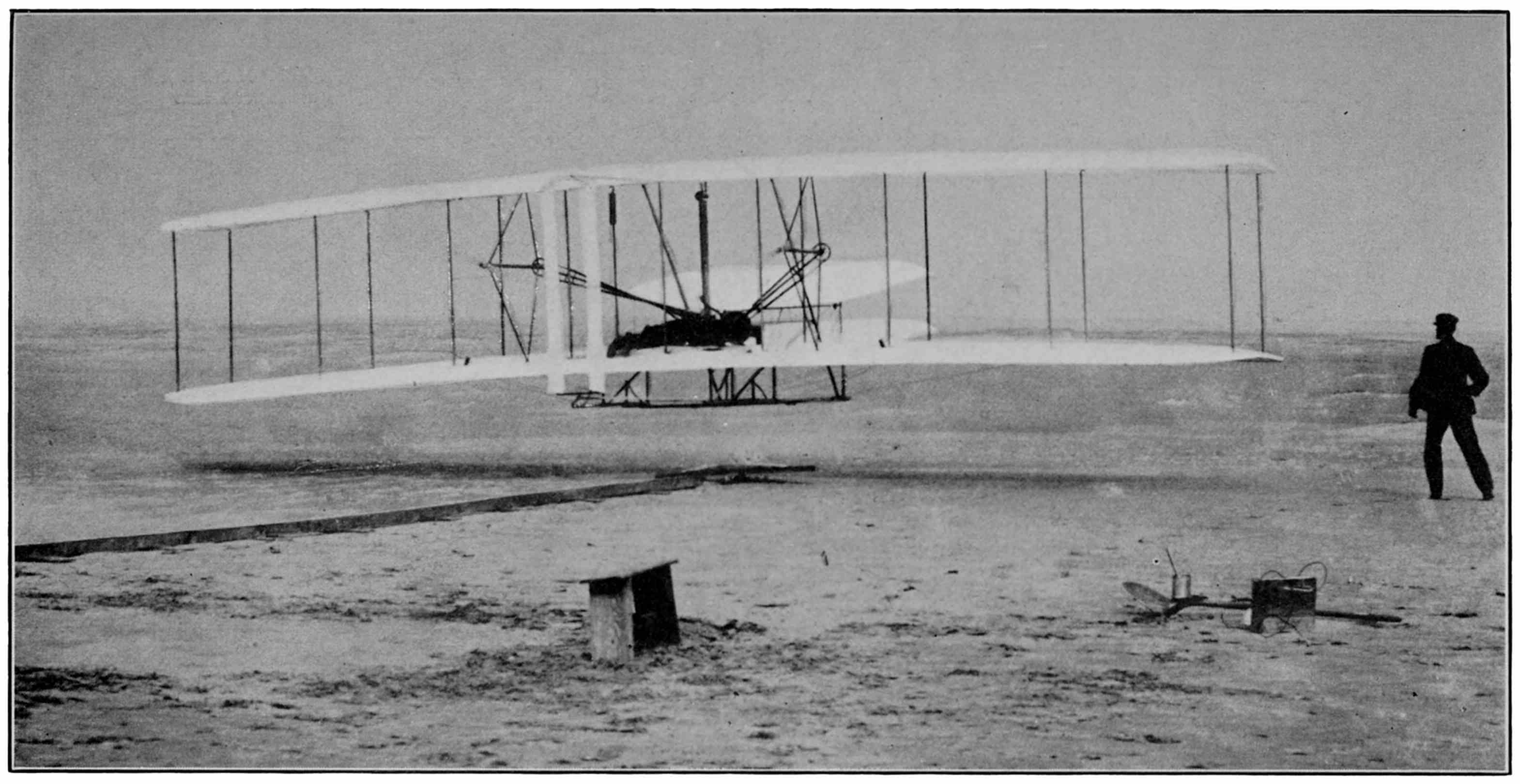

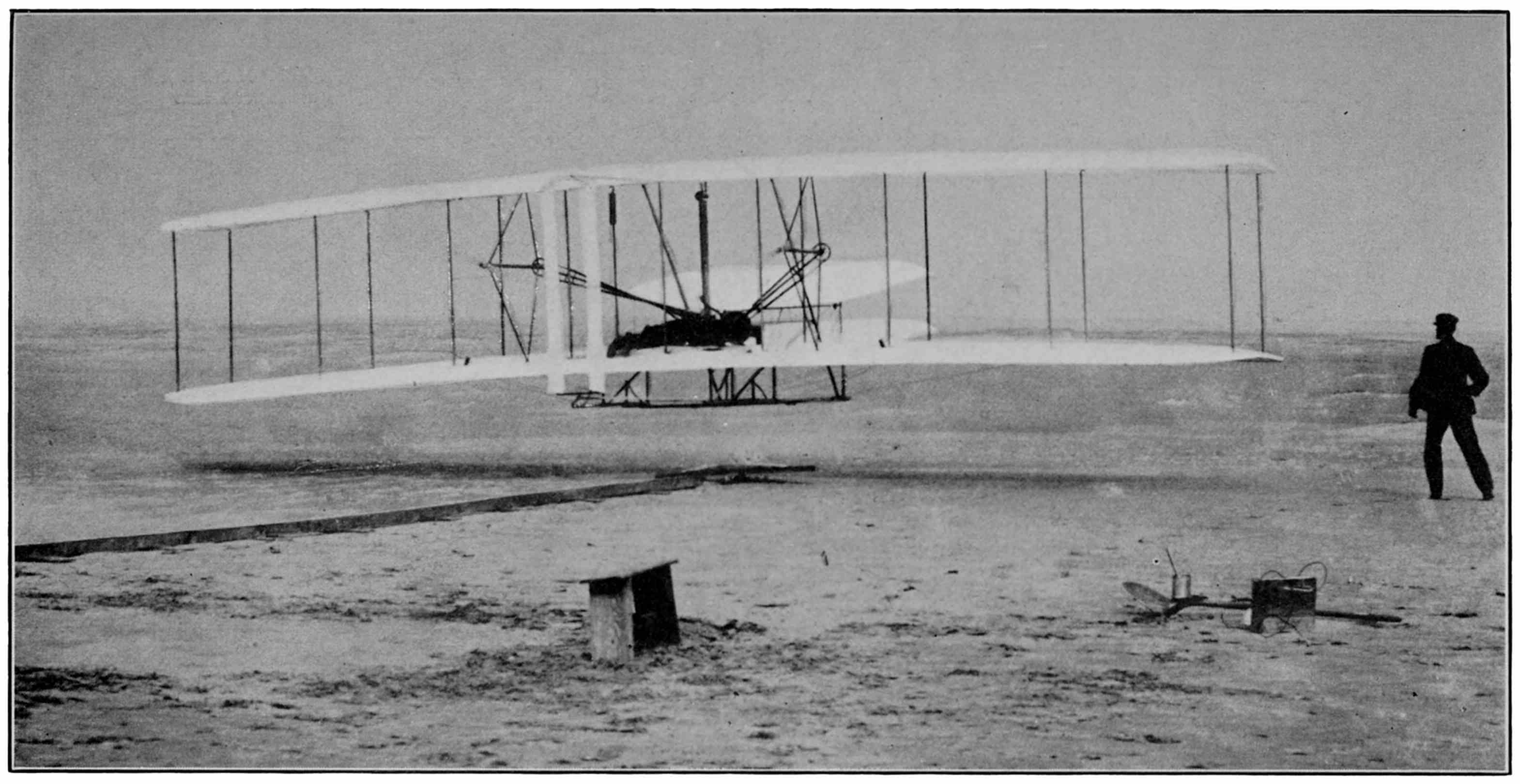

FIRST FLIGHT. The only picture made of man’s first flight in a power-driven, heavier-than-air machine, Kitty Hawk, December 17, 1903. The plane, piloted by Orville Wright, has just taken off from the monorail. Wilbur Wright, running at the side, had held the wing to balance the machine until it left the rail.

One reason why nearly everyone in the United States was disinclined to swallow the reports about flying with a machine heavier than air was that important scientists had already explained in the public prints why the thing was impossible. When a man of the profound scientific wisdom of Simon Newcomb, for example, had demonstrated with unassailable logic why man couldn’t fly, why should the public be fooled by silly stories about two obscure bicycle repair-men who hadn’t even been to college? Professor Newcomb was so distinguished an astronomer that he was the only American since Benjamin Franklin to be made an associate of the Institute of France. It was widely assumed that what he didn’t know about laws of physics simply wasn’t in books; and that when he said flying couldn’t be done, there was no need to inquire any further. More than once Professor Newcomb had written that flight without gas-bags would require the discovery of some new metal or a new unsuspected force in Nature. Then, in an article in The Independent—October 22, 1903, while the Wrights were at Kitty Hawk assembling their power machine—he not only proved that trying to fly was nonsense, but went further and showed that even if a man did fly, he wouldn’t dare to stop. “Once he slackens his speed, down he begins to fall.—Once he stops, he falls a dead mass. How shall he reach the ground without destroying his delicate machinery? I do not think that even the most imaginative inventor has yet put on paper a demonstrative, successful way of meeting this difficulty.”

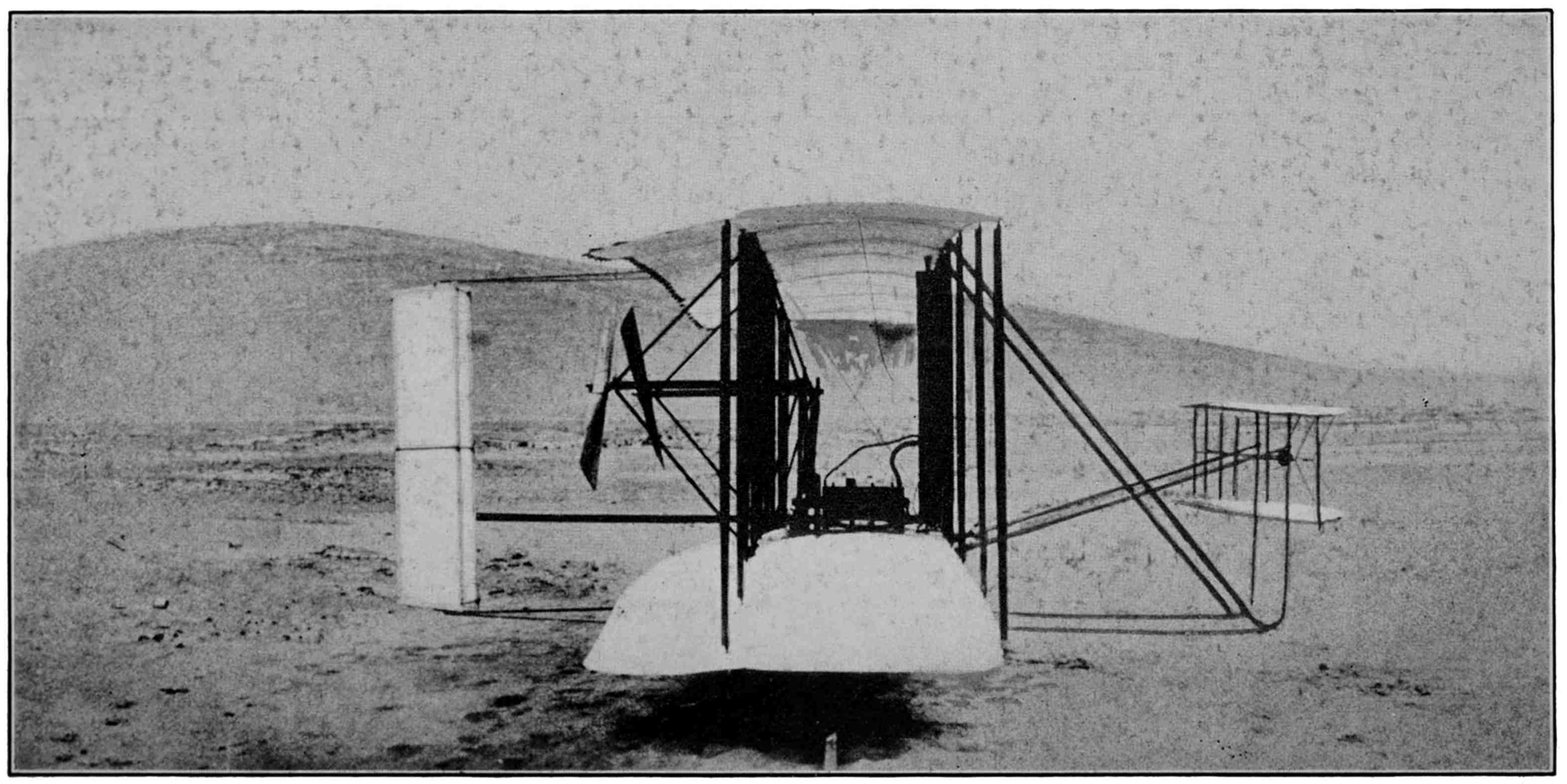

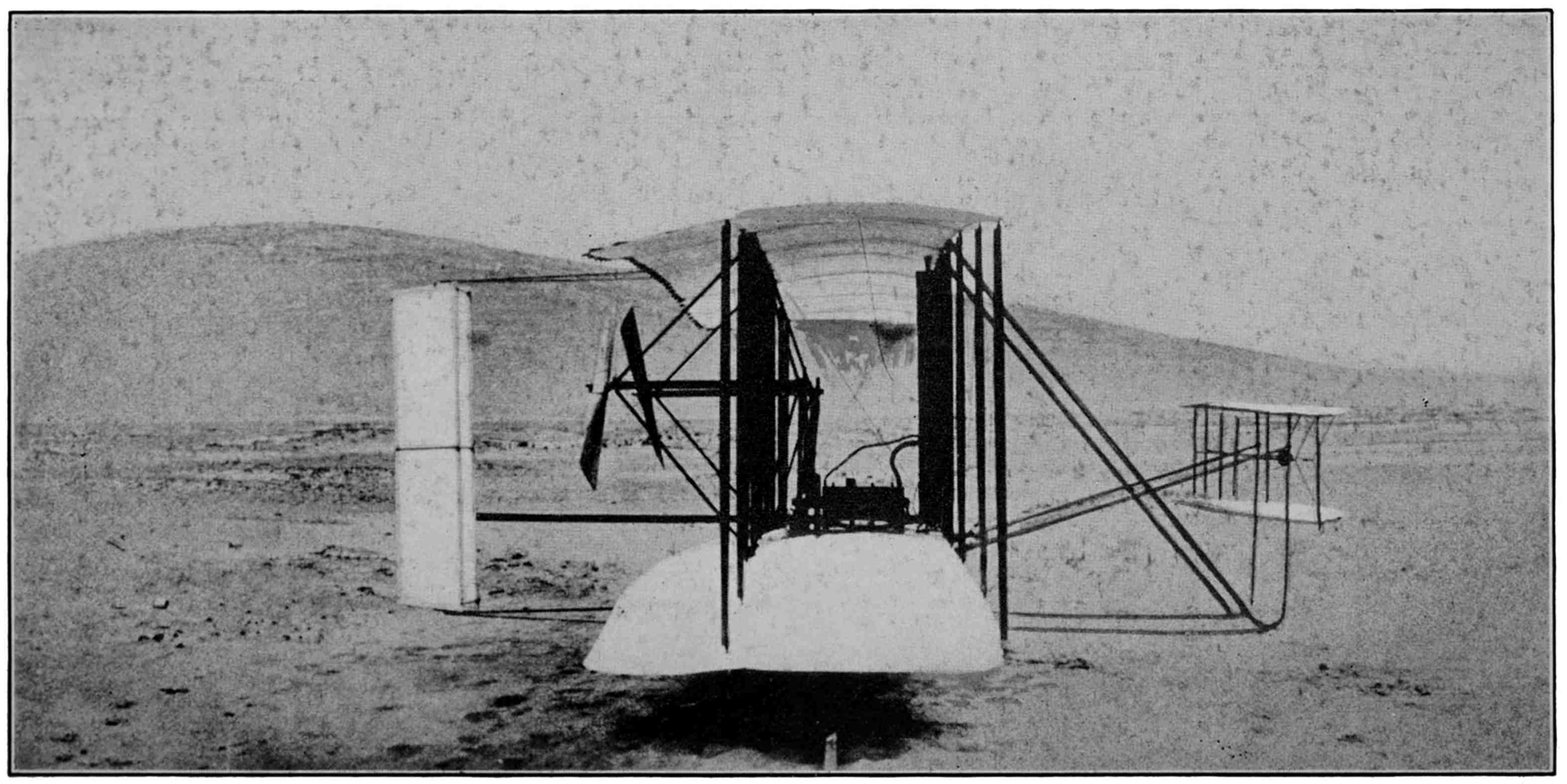

THE FIRST POWER PLANE. A side view of the 1903 plane at Kitty Hawk.

In all his statements, Professor Newcomb had the support of other eminent authorities, including Rear Admiral George W. Melville, then chief engineer for the United States Navy, who, a year or two previously, in the North American Review, had set forth convincingly the absurdity of attempts to fly.

The most recent Newcomb article was all the more impressive as a forecast from the fact that it appeared only fifteen days after one of Professor Langley’s unsuccessful attempts at flight. That is, Langley’s attempt seemed to show that flight was beyond human possibility, and then Newcomb’s article explained why it was impossible. Though these pooh-poohing statements by Newcomb and other scientists were probably read by relatively few people, they were seen by editors, editorial writers, and others who could have much influence on public opinion. Naturally, no editor who “knew” a thing couldn’t be done would permit his paper to record the fact that it had been done.

Oddly enough, one of the first public announcements by word of mouth about the Wrights’ Kitty Hawk flights was in a Sunday-school. A. I. Root, founder of a still prosperous business for the sale of honey and beekeepers’ supplies at Medina, Ohio, taught a Sunday-school class. One morning shortly before the dismissal bell, observing that the boys in the class were restless, he sought to restore order by catching their interest. Perhaps he wished to show, too, that miracles as wonderful as any in the Bible were still possible.

“Do you know, friends,” he said, “that two Ohio boys, or young men rather, have outstripped the world in demonstrating that a flying-machine can be constructed without the aid of a balloon?” He had read a brief item about the Wrights in an Akron paper.

The class became attentive and Root went on: “During the past two months these two boys have made a machine that actually flew through the air for more than half a mile, carrying one of the boys with it. This young man is not only a credit to our state but to the whole country and to the world.”

Though this was several weeks after the Wrights had first flown, no one in the class had ever heard about it, and incredulously they fired questions at the teacher.

“Where do the boys live? What are their names? When and where did their machine fly?”

Root described, not too accurately, the Kitty Hawk flights, and added: “When they make their next trial I am going to try to be on hand to see the experiment.”

An important part of Root’s business was publication of the still widely circulated magazine, Gleanings in Bee Culture, and in his issue of March 1, 1904, he told of the episode in the Sunday-school. By printing that story, the Medina bee man may possibly have been the first editor of a scientific publication in the United States to report that man could fly. (The Popular Science Monthly in its issue of March, 1904, had an article by Octave Chanute in which the flights were mentioned.) Root a little later even predicted: “Possibly we may be able to fly over the North Pole.”

The Wrights were more amused than disturbed by the lack of general recognition that flying was now possible. They inwardly chuckled when they heard people still using the old expression: “Why, a person could no more do that than he could fly!” But they knew they had only begun to learn about handling a flying-machine.