XIII

A DEAL WITH THE U. S.

WHILE in Paris, in 1907, the Wrights naturally had visits with Frank S. Lahm, who had arranged with his brother-in-law, Henry Weaver, of Mansfield, to investigate the reports from America of human flight. Lahm invited the inventors to his home and there they met his son, Lieutenant Frank P. Lahm,10 who was recuperating from an attack of typhoid fever. The younger Lahm, a former instructor at West Point, had recently spent a year at the French Cavalry School at Saumur. He, as well as his father, was much interested in aeronautics. The previous October he had won the James Gordon Bennett balloon race by starting at Paris and landing in England. Probably the only American Army officer who recognized that the airplane should now be taken seriously, he was delighted to meet the Wright brothers, with whom he now began a lasting friendship. After he had learned a little about their negotiations in France, he began to urge the United States War Department to take more interest in the airplane.

It so happened that, in September, 1907, only a few weeks after this meeting, Lieutenant Lahm was transferred by the War Department from the Cavalry to the Signal Corps, to be stationed at Washington. His first assignment was to make a tour of Europe, before returning to Washington, and report on the situation regarding dirigible aircraft in several countries. Soon afterward he returned to Washington. The presence of a man in the War Department there who felt enthusiasm for the airplane’s possibilities, and who had strong faith in the Wrights, may have had its effect on his associates. At any rate, there was now in the War Department a man who believed in the Wrights.

When Wilbur stopped in Washington shortly before Thanksgiving, 1907, en route to Dayton, on his return from France, he had a talk with General Crozier and Major Fuller of the Ordnance Department, and with General Allen, head of the Signal Corps—the organization that would conduct tests of the airplane and use it if the Ordnance Board sanctioned and provided funds for its purchase. At this meeting Wilbur stated the price the Wrights would accept ($25,000) and the performance of the machine that they were willing to guarantee. These terms, agreed upon between the brothers before Wilbur left France, were stiff enough, it was thought, to bar any competition. The Ordnance Board was to have a meeting on December 5, and Wilbur was invited to appear before it. He did so; but the meeting did not inspire him with confidence that an early contract could be obtained at the price of $25,000. The Wrights were not willing to accept less, because they thought they had better prospects abroad. However, the Signal Corps soon began drawing up specifications, and, on December 23, advertised for bids.

Inasmuch as the Wright machine was the only one in existence that could meet these requirements, and the price was understood in advance, advertising for bids may have been superfluous; but it was considered necessary to meet demands of red tape. Among specifications set forth in the advertisement for bids were these: the plane must be tested in the presence of Army officers; it must be able to carry for one hour a passenger besides the pilot, the two weighing not less than 350 lbs.; it must show an average speed of forty miles an hour, in a ten-mile test, and carry enough fuel for 125 miles. Also, the machine must have “demountability”; that is, it should be built in such a way that it could be taken apart, and later reassembled, without too much difficulty, when necessary to transport it on an army truck from one place to another.

Almost from the day the advertisements for bids appeared, the War Department was subject to editorial attacks—not because it had been so slow about interesting itself in the airplane, but because it had done so at all!

The New York Globe said:

One might be inclined to assume from the following announcement, “the United States Army is asking bids for a military airship,” that the era of practical human flight had arrived, or at least that the government had seriously taken up the problem of developing this means of travel. A very brief examination of the conditions imposed and the reward offered for successful bidders suffices, however, to prove this assumption a delusion.

A machine such as is described in the Signal Corps’ specifications would record the solution of all the difficulties in the way of the heavier-than-air airship, and, in fact, finally give mankind almost as complete control of the air as it now has of the land and the water. It would be worth to the world almost any number of millions of dollars, would certainly revolutionize warfare and possibly the transportation of passengers; would open to easy access regions hitherto inaccessible except to the most daring pioneers and would, in short, be probably the most epoch-making invention in the history of civilization.

Nothing in any way approaching such a machine has ever been constructed (the Wright brothers’ claims still await public confirmation), and the man who has achieved such a success would have, or at least should have, no need of competing in a contest where the successful bidder might be given his trial because his offer was a few hundred or thousand dollars lower than that of someone else. If there is any possibility that such an airship is within measurable distance of perfection any government could well afford to provide its inventor with unlimited resources and promise him a prize, in case of success, running into the millions.

The American Magazine of Aeronautics (later called Aeronautics) devoted its opening article in the issue of January, 1908, to pointing out the absurdity of what the War Department was trying to do.

There is not a known flying-machine in the world which could fulfill these specifications at the present moment, [declared the editorial].... Had an inventor such a machine as required would he not be in a position to ask almost any reasonable sum from the government for its use? Would not the government, instead of the inventor, be a bidder?... Perhaps the Signal Corps has been too much influenced by the “hot air” of theorizers, in which aeronautics unfortunately abounds, who have fathomed the entire problem without ever accomplishing anything; talk is their stock in trade and models or machines are beneath them because beyond their impractical nature.... Why is not the experience with Professor Langley a good guide?... We doubt very much if the government receives any bids at all possible to be accepted.

To the surprise of nearly everyone, forty-one proposals were received. Most of the bidders were the same kind of cranks the Ordnance Board had at first supposed the Wrights to be; and their bids were rejected when they failed to put up a required ten per cent of the proposed price of the plane, as a sign of good faith. Two other bidders besides the Wrights did make a ten per cent deposit. One of these, J. F. Scott, of Chicago, had made a bid of $1,000, and promised delivery of a plane in 185 days. Another was A. M. Herring. His price was $20,000; delivery to be in 180 days. The Wrights’ bid was $25,000, with delivery promised in 200 days.

Receipt of these unexpected bids created a problem. Everyone assumed that none of the bidders except the Wrights had anything practical to offer; and yet the government would be expected to accept the lowest bid and let the winner show what he could do. No matter how dismally he failed to meet requirements, dealing with him would take up time and cause delays.

General Allen, of the Signal Corps, went to Secretary of War Taft to inquire how the War Department might get around the difficulty. Taft said they could accept all legal bids and as only the Wrights could meet the requirements, the others would be eliminated. The only difficulty was that even if no money would ever be paid to the other bidders, yet it would be illegal to accept the bids unless enough money to pay for whatever was ordered was known to be available. However, Taft suggested a way around that. He knew that the President had at his disposal an emergency fund to do with as he saw fit. If the President wished to he could guarantee that all bidders would be paid if they met the tests.

General Allen, accompanied by Captain Charles De Forest Chandler and Lieutenant F. P. Lahm, Signal Corps officers, called upon President Roosevelt who promptly agreed with Taft’s suggestion. He told them to accept all bids and that he would place funds at their disposal to meet legal technicalities. The Signal Corps then agreed to buy planes from all three bidders if they met the necessary requirements.

One of those bidders soon eliminated himself by asking the Government to return his ten per cent deposit. Though the government was not obliged to return the deposit, it nevertheless did so. Herring, the only remaining legal bidder besides the Wrights, hung on a while longer.

What A. M. Herring had in mind was simply to obtain the contract in consequence of his lower price and then try to sublet it to the Wrights. He even had the effrontery to go to Dayton to see the Wrights and make such a proposal. Naturally, they were not interested.

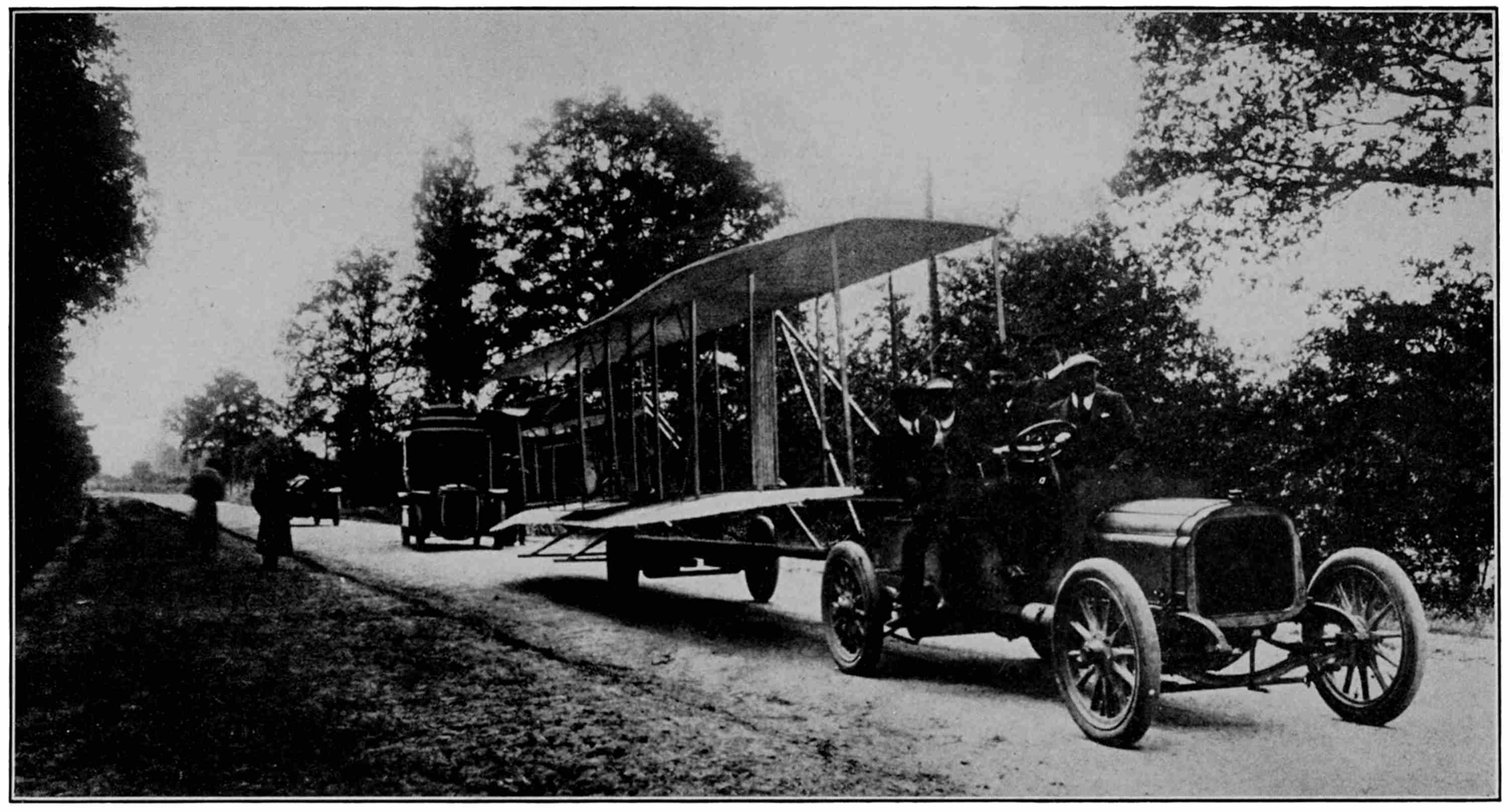

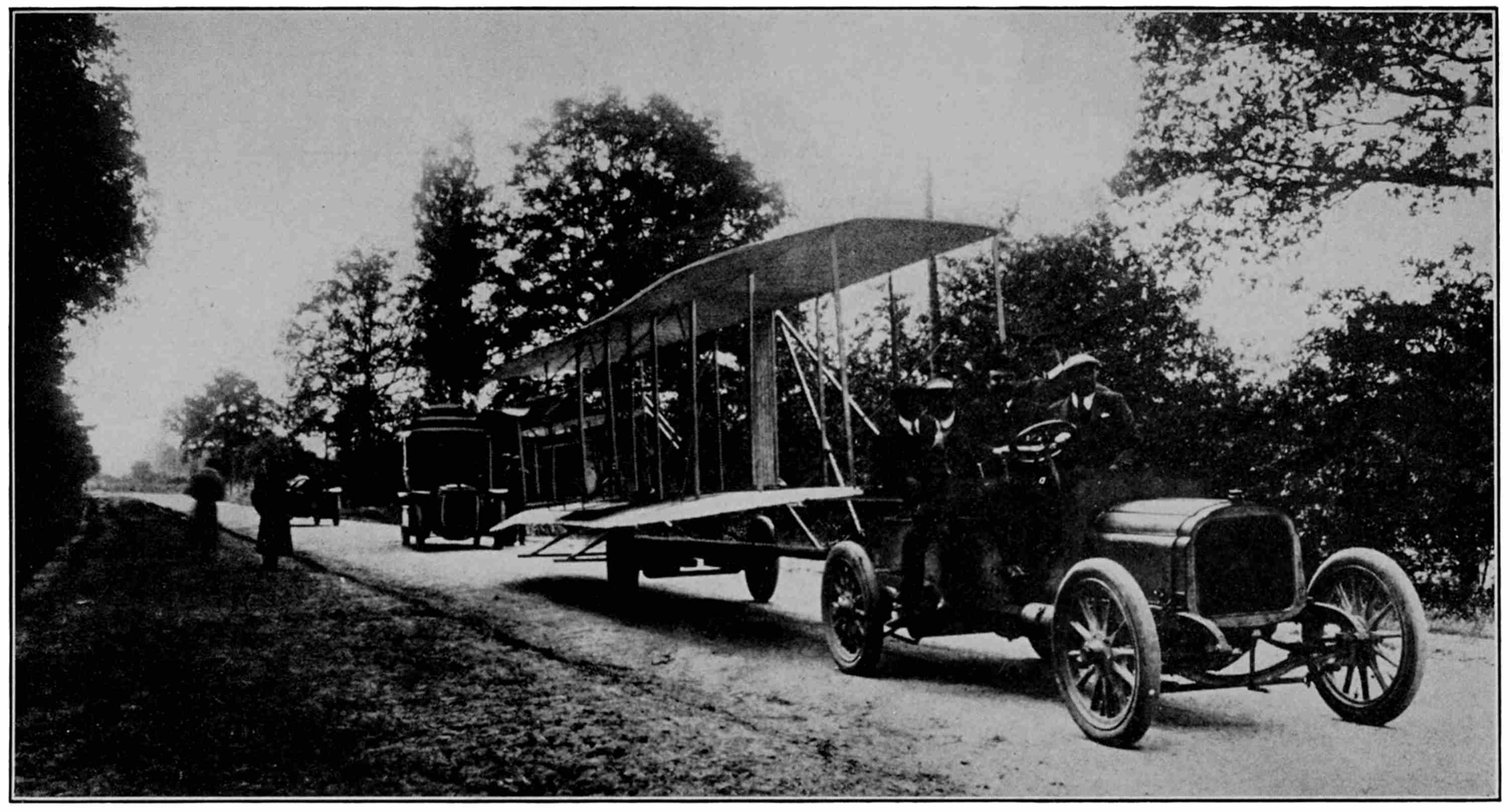

THE WRIGHT PLANE IN FRANCE. The plane is being hauled from one field to another, near Le Mans, France, in August, 1908.

The Wrights’ bid was accepted on February 8, 1908.

As it happened, this was not the only important contract the Wrights entered into at about that time. On March 3, three weeks after the Signal Corps had accepted their bid, they closed a contract with Lazare Weiller, a wealthy Frenchman, to form a syndicate to buy the rights to manufacture, sell, or license the use of the Wright plane in France. Upon completion of certain tests of the machine, the Wrights were to receive a substantial amount in cash, a block of stock, and provision for royalties. The French company would be known as La Compagnie Générale de Navigation Aérienne. A member of the syndicate was M. Deutsch de la Meurthe who had taken steps toward forming a French company some time previously.

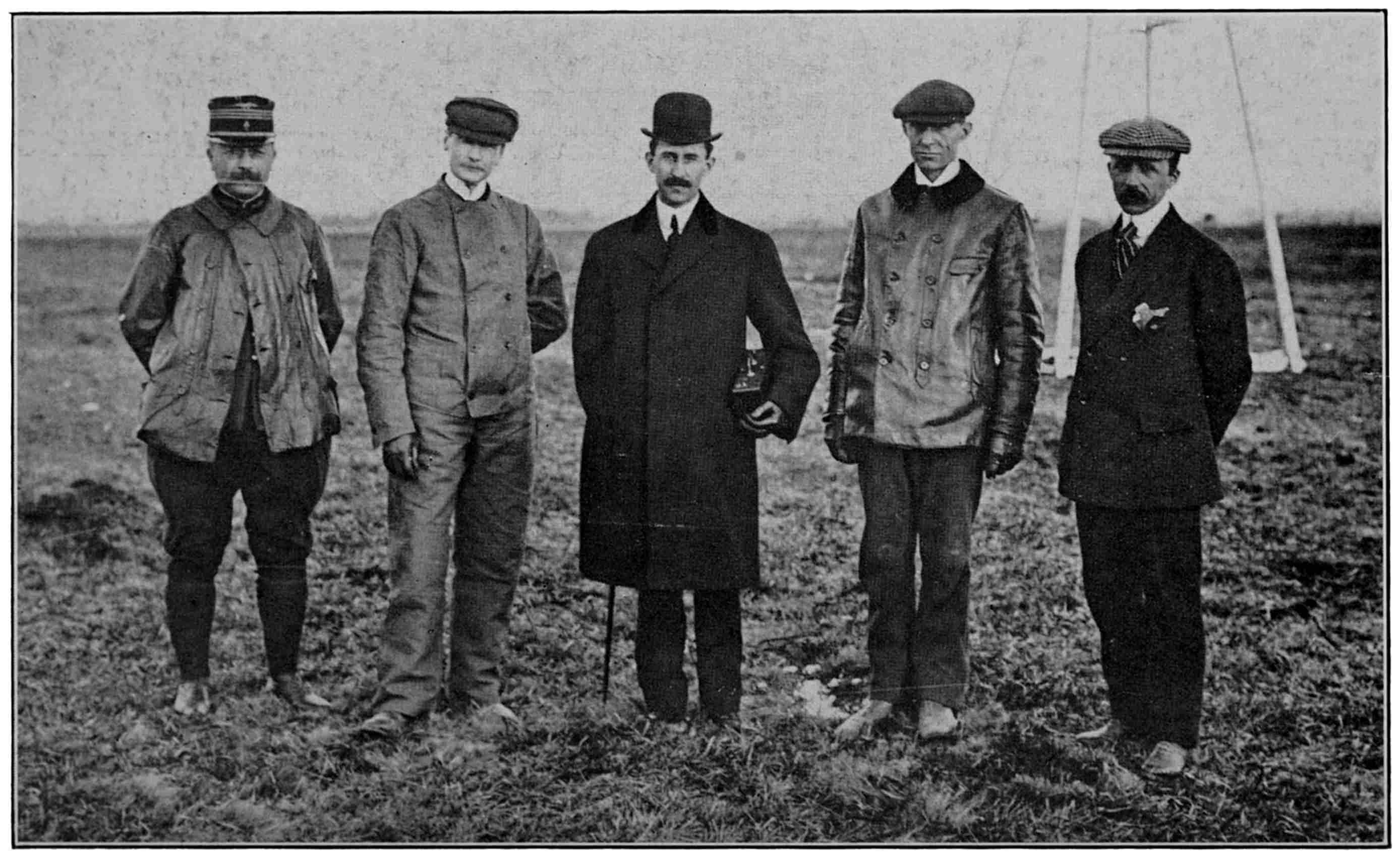

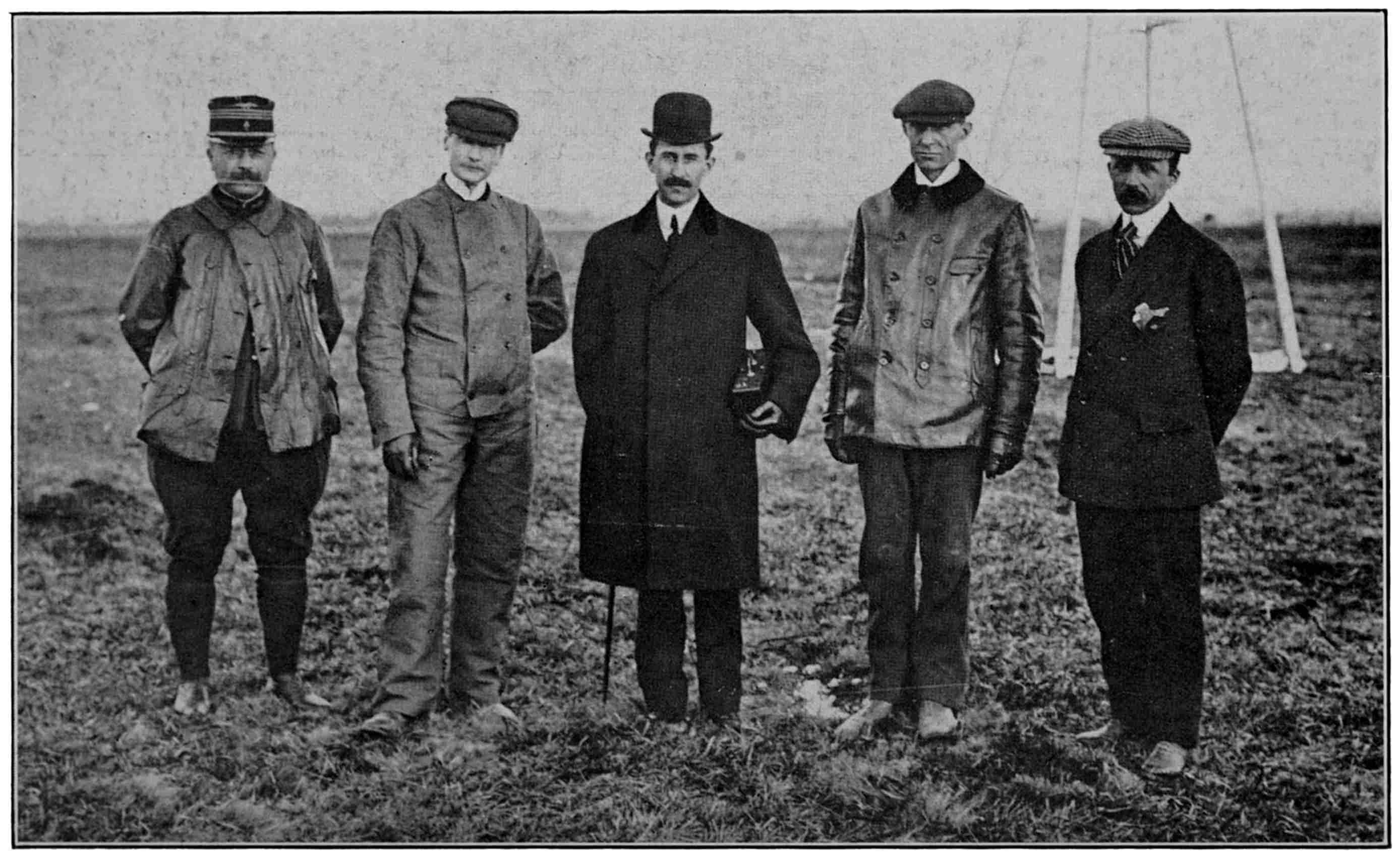

THE WRIGHTS AND WILBUR’S FRENCH PUPILS. Left to right, Captain Lucas-Girardville, Comte Charles de Lambert, Orville Wright, Wilbur Wright, and Paul Tissandier, at Pau, France, early in 1909.

One provision of the U. S. War Department contract was that the Government could deduct ten per cent of the purchase price for each mile per hour that the machine fell short of the forty-mile goal. That is, if it went only thirty-nine miles an hour, the Wrights would be docked ten per cent; if only thirty-eight miles, another ten per cent, and so on. If the machine did not do at least thirty-six miles an hour, then the Government didn’t have to accept it at all. On the other hand, the Wrights would receive a ten per cent bonus for each mile per hour they attained above forty.

It was the intention of the Signal Corps, and the Wrights so understood it, that these reduced or additional payments would be for either a mile or a fraction of a mile. But a Government legal department made a surprising interpretation of that part of the contract. If at the time of the tests the plane went 40-99/100 miles, the Wrights would not be paid for more than 40; but if the plane fell short of 40 miles an hour by only 1/100 of a mile, or even less, then they would be docked for a full mile.

(Orville did not learn of that astounding example of the legal mind at work until after he arrived at Washington to prepare for the tests and it was then too late to build a faster plane. But in the final tests the next year, he had a plane that he knew would give the buyer no opportunity to take advantage of what he regarded as a one-sided interpretation of the contract.)

Though the Wrights had done no flying since October, 1905, they had done much work on improving both plane and engine. Their newest engine, capable of producing about thirty-five horsepower continuously, was also so much better as to reliability that now long flights could be made without danger of failure of the motive power.

During all their experiments at the Huffman pasture they had continued to ride “belly-buster,” as a boy usually does when coasting on a sled. Lying flat in that way and controlling the mechanism partly by swinging the hips from one side to the other was good enough for the experimental stages of aviation; but the Wrights knew that if a plane was to have practical use the pilot must be able to take an ordinary sitting position and do the controlling and guiding with his hands and feet as in an automobile. It was not all fun lying flat for an hour at a time with head raised to be on the lookout for possible obstacles. “I used to think,” said Orville in later years, “the back of my neck would break if I endured one more turn around the field.”

The brothers therefore had adopted a different arrangement of the control levers, for use in a sitting position, and a seat for a passenger. Moreover, the machine could be steered from either seat and thus was suitable for training other pilots if occasion should arise. The plane sent to France for possible trials in 1907 was thus equipped. They revamped the machine they had used at the Huffman pasture in 1905, and installed their later improvements. It now had an engine with vertical instead of horizontal cylinders. With this machine they would go to Kitty Hawk and gain needed practice in handling their new arrangement of the control levers.

The United States Government tests would be made at Fort Myer, Virginia, near Washington. Delivery of the machine had to be made by August 28, and the tests themselves were to begin shortly afterward, in September. But at about that same time, one of the brothers would make a demonstration in France. They had not yet decided which of them would fly at Fort Myer and which should go to France. But both had to be well prepared and there was no time to lose. They must be established at Kitty Hawk as soon as possible.

Wilbur Wright set out for Kitty Hawk ahead of Orville and arrived there April 9, 1908. He was joined within a week by a mechanic from Dayton, Charles W. Furnas. First of all, it was necessary to do much rebuilding of the camp. The buildings had not only suffered from storms, but had been stripped of much timber by persons who supposed the Wrights had permanently abandoned them. The plane was shipped in crates from Dayton April 11, but had to be left for some time in a freight depot at Elizabeth City until the new shed was completed at Kitty Hawk. Both Orville and the plane reached there on April 25.

It might have been expected that with at least two governments now showing interest in the Wright plane, each of the brothers would have been besieged en route by reporters and others. But the general public, including reporters, still seemed disinclined to believe in human flight. At about the same time that the Wrights were preparing to go to Kitty Hawk, a publisher brought out a new novel by H. G. Wells, Tono-Bungay, in which the leading character built a gliding machine “along the lines of the Wright brothers’ airplane,” and finally a flying-machine. That stirred one or two American book reviewers to chide the author for putting such fantastic material into a tale otherwise plausible.

Because of the persistence of that kind of incredulity, the Wrights did not expect many sightseers, least of all newspapermen, at Kitty Hawk during their preparations for government tests. Therefore they did not think it necessary to keep their plans secret. Though they weren’t seeking reporters, neither were they trying to avoid them. They simply went ahead without giving any thought to newspapermen one way or another. But the Wrights were about to be discovered.

Not until May 6 did either of the brothers make a flight. But the newspapers, instead of ignoring what the Wrights had done, now began to report what they had not done. On May 1, the Virginian-Pilot, of Norfolk (the same paper that had reported, not too accurately, the first flight of an airplane), carried a wild tale that one of the Wright brothers had flown, the day before, ten miles out over the ocean! Practically the same story was widely published the next day. Katharine Wright on May 2 telegraphed her brothers that “the newspapers” had reported a flight. As the Wrights later learned, the B. Z. Mittag, in Berlin, carried a dispatch from Paris: “From America comes the news that the Wright brothers for the first time have made in public a controlled flight. The flight was made on April 30, at Norfolk, Va., before a U. S. Government Commission.”

That same story must have reached London, for the Wrights received a cablegram from Patrick Alexander: “Very hearty congratulations.”

Joseph Dosher, who had been the Weather Bureau man at Kitty Hawk in 1903, but was now stationed 30 miles north of Kitty Hawk, telephoned to the Kill Devil life-saving crew, on May 2, seeking information about the Wrights, presumably at the request of some newspaper. That same day, the Greensboro (N. C.) News published a telegram from Elizabeth City, dated May 1, saying that the Wright brothers “of airship fame” were at Nag’s Head with their “famous flying-machine.”

On May 1, the New York Herald had wired to the Weather Bureau operator at Manteo, on Roanoke Island, for information. And on May 2, the Herald published an item with a Norfolk date line, that the Wrights were reported to have flown “over the ocean.” This dispatch appeared also in the Herald’s Paris edition. Just below the report in the Paris edition was an editorial comment that if the Wrights had actually flown two miles, then they had broken the records of Delagrange and Farman in France. The Herald editor evidently was still unaware that long before Delagrange, Farman, or other Wright copyists abroad had even left the ground in flight, the Wright brothers had flown twenty-four miles.

Inasmuch as the Wrights had not yet begun their flights of 1908, it was not easy for the New York Herald to obtain confirmation or more details about the imaginary flight out over the ocean. No regularly employed newspaperman at Norfolk wanted to go to Kitty Hawk on what might be a wild goose chase. But D. Bruce Salley, a free lance reporter at Norfolk, was willing to make the trip.

Salley reached Manteo on May 4, and the Wright brothers’ records show that he came to their camp the next day. He told the brothers he had been asked by a New York paper to investigate the story of their flight over the ocean. The day after Salley’s visit, the Wrights did make their first flight of the season, and though Salley did not see it, he learned about it by phone from one of the men at the Kill Devil life-saving station. His informant told him that one of the Wrights had flown at least 1,000 feet, at about sixty feet above the ground.

Salley immediately sent a query from Manteo, giving briefly the gist of the story, to a list of papers he hoped would be interested. Most of the papers ignored the message; but the telegraph editor of the Cleveland (Ohio) Leader not only wasn’t interested but was indignant that his intelligence should be insulted by the offer of so improbable a tale. He declined to pay the telegraph toll for the short message, even though at the night press rate of only one-third of a cent a word the cost could hardly have been more than a dime. His only reply to Salley was an admonition to “cut out the wild-cat stuff.” Salley, now equally indignant, wired back offering to give names of well-known persons who could testify to his reliability; but the Cleveland editor paid no further attention.

When Salley’s query reached the office of the New York Herald, it put the editors in a quandary. Though they had printed the brief report about a flight that hadn’t occurred, now they were beginning to wonder if all the reports about the Wrights weren’t fakes. Yet they knew that the owner of the paper, James Gordon Bennett, living in Paris, would almost certainly discharge any editor responsible for omitting the story if it were true. They decided, with misgivings, to print the story and it appeared the next morning on the first page of the Herald, though not in the most prominent position.

Then the editors determined to send a staff man to Kitty Hawk for the facts. They picked for this job their star reporter, brilliant, lovable Byron R. Newton—later to become Assistant Secretary of the Treasury, and afterward Collector of Customs in New York—one of the ablest newspapermen of his time. If the Wrights proved to be fakers no one could do a better job than “By” Newton at exposing them.

Other editors, too, decided that the time had come to get the “lowdown” on the Wright brothers. By the time Newton reached the little boarding place, the Tranquil House, in Manteo, he had been joined by two other correspondents: William Hosier, of the New York American, and P. H. McGowan, of the London Daily Mail. The next day two others arrived: Arthur Ruhl, writer, and James H. Hare, photographer, for Collier’s Weekly.

The newly arrived correspondents, noting the desolate isolation of Kitty Hawk, thought it probable enough that the Wrights must prefer to be let alone. Perhaps, they thought, if intruders came, the Wrights wouldn’t fly at all. They decided that if the Wrights were secretive, they themselves would be no less so. They would hide in the pine woods, as near as possible to the Wright camp, and observe with field glasses what happened. That meant a short walk to a wharf on Roanoke Island, five miles by sailing boat to Haman’s Bay, across the sound, and then a walk of a mile or so over the sand to the place where they should secrete themselves. They made a dicker with a boatman to take them all back and forth each day and act as their guide. Provided with food and water, field glasses, and cameras, they set out about 4 o’clock each morning from May 11 to May 14 to keep their vigil. Hour after hour they fought mosquitoes and woodticks and sometimes were drenched by rain. But to their astonishment they several times witnessed human flight.

The first flight any of them witnessed was early in the morning of May 11. “For some minutes,” wrote Newton, “the propeller blades continued to flash in the sun, and then the machine rose obliquely into the air. At first it came directly toward us, so that we could not tell how fast it was going except that it appeared to increase rapidly in size as it approached. In the excitement of this first flight, men trained to observe details under all sorts of distractions forgot their cameras, forgot their watches, forgot everything but this aerial monster chattering over our heads.”

However, “Jimmy” Hare got a good photograph of that flight.

On May 14, the correspondents saw what no person on earth had ever seen before—a flying-machine under complete control carrying two men. First Wilbur made a short flight with Charles W. Furnas as passenger, and then Orville flew with Furnas for nearly three minutes.

Newton predicted in his diary just after that: “Some day Congress will erect a monument here to these Wrights.”11

The last flight on May 14, made by Wilbur Wright, ended in an accident. Wilbur had pulled a wrong lever. Repairs would have taken a week, and as the time the brothers could spare had elapsed, the experiments stopped. But after removing the engine and other machinery for shipment to Dayton, the Wrights left the plane in the shed at Kitty Hawk, thinking they might return. The ending of these trials brought no grief to the correspondents who had been getting up before daylight each morning, and returning to Manteo late each afternoon, footsore and tired, with their dispatches still to be written.

One night’s dispatches had brought unexpected trouble for “By” Newton. Though his report had been filed ahead of McGowan’s, in plenty of time to be relayed from his paper’s New York office to Paris and appear in the next morning’s issue of the Paris edition, a needless delay occurred in New York. In consequence, Newton, through no fault of his own, was “scooped” by McGowan the next day in the continental edition of the London Daily Mail. When James Gordon Bennett, proprietor of the New York Herald, observed that his Paris Herald failed to have any account of the sensational flights at Kitty Hawk the day before, as reported in the rival Daily Mail, he was furious. During the two seasons when the Wrights had flown a total of 160 miles at Huffman prairie, Bennett, with scores of reporters at his disposal, had failed to learn the truth of what the Wrights had done. But now when he thought a reporter had missed a story about them, he did not wait to make inquiries but promptly sent a cable to New York ordering Newton suspended from the staff. Under Bennett’s way of conducting his papers, suspension usually was a preliminary to permanent discharge.

Though he was reinstated after he had sent to Bennett a review of the facts, along with some affidavits, Newton, all the rest of his life, felt a grievance against Bennett and the Herald.

Incidentally, McGowan’s “scoop” in the continental edition of the Daily Mail which had so disturbed Bennett, was not accepted as truth by everyone who read it. Charles A. Bertrand, in one of the Paris papers, May 15, published this comment: “He [McGowan] depicts the flight in a manner that does honor to his imagination. If the Wrights hadn’t been seen in Europe, one would be justified in believing their very existence as uncertain as their apparatus.”

During the several days the correspondents were at Kitty Hawk, the Wrights knew they were being observed. From time to time they caught glimpses of men’s heads over the hilltop in the distance. Moreover, they heard each day, from members of a life-saving crew, just how many visitors had come. But they simply thought it was a good joke on the mysterious observers, whoever they were.

Arthur Ruhl, of Collier’s, had met the Wrights in Dayton about a year before. On May 14, before the final flight, he came over to the camp. But he said nothing about being a member of the group that had been observing the flights.

The Wrights invited Ruhl to stay for lunch. But he declined. He seemed to the Wrights ill at ease and anxious to get away. At a meeting with him some time afterward they learned why. He had come against the wishes of the other correspondents and was afraid he might give away the fact that they were in the near-by woods.

On May 15, the day after the crash, when it was evident that there would be no more flights, McGowan, of the Daily Mail, went to the camp, accompanied by still another correspondent who had just arrived, Gilson Gardner, of the Washington office of the Newspaper Enterprise Association. McGowan remarked that he had once visited Octave Chanute’s camp at Dune Park, near Chicago, in 1897 for the Chicago Tribune. Another visitor at the camp, a day or two before that, was a young man named J. C. Burkhardt, dressed in a brand-new outfit of hunting togs. He was a college boy who had come all the way from Ithaca just to satisfy his curiosity.

“What would you have done,” Orville Wright was asked, afterward, “if all those correspondents had come right to your camp each day and sat there to watch you?”

“We’d have had to go ahead just as if they weren’t there,” he replied. “We couldn’t have delayed our work. There was too much to do and our time was short.”

That the Wrights would have treated the correspondents politely enough was indicated in a letter from Orville Wright to Byron Newton, dated June 7, 1908. Immediately after his return to New York, Newton had written graciously to the Wrights, enclosing clippings of his dispatches to the Herald, and expressing his admiration for them and their achievements.

“We were aware of the presence of newspapermen in the woods,” wrote Orville in reply; “at least we had often been told that they were there. Their presence, however, did not bother us in the least, and I am only sorry that you did not come over to see us at our camp. The display of a white flag would have disposed of the rifles and shotguns with which the machine is reported to have been guarded.”

After publication of many dispatches from these eyewitnesses at Kitty Hawk and front page headlines, it might have been expected that the fact of human flight would now be generally accepted. As Newton had written to his paper, there was “no longer any ground for questioning the performance of these men and their wonderful machine.” Ruhl in Collier’s had told how the correspondents had informed the world that “it was all right, the rumors true—that man could fly.” Yet even such reports by leading journalists still did not convince the general public. People began to concede that perhaps there might be something in it, but many newspapers still did not publish the news. When Newton sent an article, some weeks later, on what he had seen at Kitty Hawk, to a leading magazine, it came back to him with the editor’s comment: “While your manuscript has been read with much interest, it does not seem to qualify either as fact or fiction.”