XV

WHEN WILBUR WRIGHT WON FRANCE

WILBUR WRIGHT reached France in May, 1908, to fly the Wright machine that for a year had been in its crate at the customs warehouse in Le Havre. If he accomplished what he expected, final details of the Wrights’ business arrangement with the recently formed French syndicate would be carried out.

As during the previous stay, when both the Wright brothers were in Europe, Wilbur kept in close touch with Hart O. Berg, European associate of Charles R. Flint & Co., the Wrights’ business representatives in all except the English-speaking countries. One of the first questions to be settled was where the actual demonstration of the Wright plane should take place. Naturally, there were not yet any areas in Europe designated as flying fields.

The locality for the flights was determined in consequence of the courtesies of Léon Bollée, an automobile manufacturer, who had a factory at Le Mans, about 125 miles from Paris.12 When Bollée learned that Wilbur Wright was in France and looking for a suitable field, he sent a message to Wilbur suggesting that a satisfactory place could doubtless be found near Le Mans where there was a great stretch of level country. He added that Wilbur would be welcome to use a wing of the Bollée factory for assembling his plane. Wilbur Wright and Hart O. Berg took a train to Le Mans where they spent several hours “looking for a good pasture.” The most nearly ideal field for their purpose was a large open area at Auvours, about five miles from Le Mans, used by the French war department for testing artillery; but it was not then available. Another place they noticed was the Hunaudières race track. The oval field within the track appeared to be large enough for their needs. There were a few trees, but Wilbur said he could easily steer clear of them. The next day, in Paris, M. Nicolai, president of the Jockey Club and principal owner of the Hunaudières race track, agreed to the use of the field, at a monthly rental, for as long as needed.

Now the crated Wright plane was shipped from Le Havre to the Bollée factory and, late in June, Wilbur set to work there. He assembled the working parts and put the motor and cooling system to a series of rigid tests. On July 4 Wilbur met with a painful accident. A rubber connection in the cooling system burst and he was badly scalded on his left arm by hot water. This was one of several unavoidable delays that made many skeptics think it would be a long time before Wilbur would attempt a public demonstration. One Paris newspaper said: “Le bluff continue.” Wilbur had been quoted as saying that the tests would be “child’s play,” and “jeu d’enfant” was often repeated, with sarcasm, by the incredulous.

Painful as his burns were, Wilbur saw a funny side to the accident and sent home a hilarious letter about the French doctor who came “with a keg of oil” to apply to the blisters.

Shortly afterward, Wilbur wanted a coiled wire spring to insert in a hose used in the cooling system, to prevent the hose from collapsing from suction. A French mechanic who had been assisting him went with him to a near-by factory to have the coil made. Not knowing any French, Wilbur could not follow the long conversation he overheard, but they came away without the coil. It seemed strange to Wilbur that the kind of wire needed should not have been easily obtainable and he spoke of this to the man who had been his interpreter.

But, said the Frenchman, the wire was available.

“Then,” asked Wilbur, in surprise, “why didn’t we get it?”

Oh, explained the Frenchman, because when he and the man at the factory talked it over it didn’t seem to them that using a coiled wire spring in the way Wilbur had in mind was a sound idea!

While working on his machine at the Bollée factory, Wilbur did something, probably just because it seemed the natural thing to do, with no thought of the impression it would make, that delighted the hearts of the factory employees. He kept the same hours that the others did and his whole behavior was as if he were simply one more workman. When the whistle blew for the noon hour, he knocked off along with the others, and went, in overalls, to lunch. This lack of any sign of aloofness caused much favorable comment.

Wilbur’s greatest admirer, however, was Léon Bollée himself. Though they had no common language, they managed to exchange ideas and formed a warm friendship. Bollée, a jolly rotund man with a saucy little beard, was ever ready to be of any service. Incidentally, though Bollée had no thought of personal gain when he generously offered the use of space in his factory, the fact that Wilbur worked on his plane there did not hurt the sale of Bollée cars.

But the work was soon transferred from the Bollée factory to the field at Hunaudières where a hastily constructed hangar had been built. Another item of preparation was the setting up of a launching derrick, similar to the one the Wrights had first used in their experiments at the Huffman pasture. Huge weights were attached at one end of a rope which ran over pulleys and had a metal ring at the other end to be caught on a hook at the front of the plane. When the plane shot forward, the rope automatically dropped away. As at previous trials, the plane when ready to take off rested on a small truck having two flanged wheels that ran on a single-rail, iron-shod, wooden track, about sixty feet long.

Not until August 8, did Wilbur attempt his first flight. A good-sized crowd was present, the majority from Le Mans and the near-by countryside, but it included many members of the Aéro Club of France and various newspaper representatives from Paris.

In describing the scene, years afterward, Hart O. Berg said: “Wilbur Wright’s quiet self-confidence was reassuring. One thing that, to me at least, made his appearance all the more dramatic, was that he was not dressed as if about to do something daring or unusual. He, of course, had no special pilot’s helmet or jacket, since no such garb yet existed, but appeared in the ordinary gray suit he usually wore, and a cap. And he had on, as he nearly always did when not in overalls, a high, starched collar.”

At least one man among the spectators felt certain the flight would not be a success. That was M. Archdeacon, prominent in the Aéro Club. So sure was M. Archdeacon that Wilbur Wright would be deflated that, as the time set for the flight approached, he was explaining to those near him in the grandstand just what was “wrong” about the design of the Wright machine, and why it could not be expected to fly well.

Wilbur’s immediate preparations had been made with great care. First of all, the starting rail had been set precisely in the direction of and against the wind. The engine was started by two men, each pulling down a blade of the two propellers and the plane was held back by a wire attached to a hook and releasing trigger near the pilot’s seat. After the engine was warmed up, Fleury, Berg’s chauffeur, took hold of the right wing. Wilbur released the trigger and the plane was pulled forward by the falling weights. Fleury kept it in balance until the accelerating speed left him behind. By the time it had reached the end of the rail, the plane left the track with enough speed to sustain itself and climb.

At some distance, directly in front of Wilbur as he started to rise, were tall trees, but they gave him no concern. He bore off easily to the left and went ahead in a curve that brought him back almost over the starting point. Then he swung to the right and made another great turn. Most of the time he was thirty or thirty-five feet above the ground. He was in the air only one minute and forty-five seconds, but he had made history.

The crowd knew well they had “seen something” and behaved accordingly. In the excited babel of voices one or two phrases could be heard again and again. “Cet homme a conquis l’air!” “Il n’est pas bluffeur!” Yes, truly Wilbur had conquered the air, and he was no bluffer. That American word “bluffer” had been much used during the time that reports from the United States about the Wrights had been stirring controversy in France. Now “bluffeur” became, more than ever, a part of the French language. “To think that one would call the Wrights ‘bluffeurs’!” lamented the French press over and over again.

For the next few minutes after Wilbur landed, Berg was kept busy laughingly warding off agitated Frenchmen who sought to bestow a formal accolade by kissing Wilbur in the French manner on both cheeks. He suspected that Wilbur might consider that carrying enthusiasm too far.

One of the skeptical members of the Aéro Club, Edouard Surcouf, a balloonist, had arrived at the field late, barely in time to see Wilbur in the air. Now he was about the most enthusiastic of all. He rushed up to Berg, exclaiming: “C’est le plus grand erreur du siècle!” Disbelieving the claims of the Wrights may not have been the biggest error of the century, but obviously it had at least been a mistake.

The only person who offered criticism or minimized the brilliance of his feat was Wilbur Wright. When asked by a reporter for the Paris edition of the New York Herald if he was satisfied with the exhibition, he replied, according to that paper: “Not altogether. When in the air I made no less than ten mistakes owing to the fact that I have been laying off from flying so long; but I corrected them rapidly, so I don’t suppose anyone watching really knew I had made any mistake at all. I was very pleased at the way my first flight in France was received.”

A crowd of Aéro Club members and other admirers were insistent that Wilbur should go back to Paris with them to celebrate the achievement at the best dinner to be obtained in that center of inspired cooking. But Wilbur just thanked them and said he wished to give his machine a little going over. Early that evening, so the newspapers reported, “he was asleep at the side of his creation.”

The French press the next day not only treated the flight as the biggest news, but was unsparing in its praise, as were various rivals in the field of aviation who were quoted. All admitted that there was a world of difference between the best French plane yet produced and the one Wilbur Wright had just demonstrated. The Figaro said: “It was not merely a success but a triumph; a conclusive trial and a decisive victory for aviation, the news of which will revolutionize scientific circles throughout the world.” Le Journal observed that: “It was the first trial of the Wright airplane, whose qualities have long been regarded with doubt, and it was perfect.”

Louis Bleriot, member of the Aéro Club, wealthy manufacturer of automobile headlights, and himself a flyer, was quoted in Le Matin as saying: “The Wright machine is indeed superior to our airplanes.”

As early as May, 1908, when the Wrights were still at Kitty Hawk, the Frenchman, Henri Farman, had issued a challenge to them to participate in a flying contest, for $5,000—later raised to $10,000. But the challenge, made only in public prints, was never sent directly to the Wrights. It may have been simply what today would be called a “publicity stunt.” (Farman’s best straightaway flight of about a mile and a quarter had been made at Issy, France, on March 21, 1908.) Nothing more was heard of the Farman challenge now. A French paper commented that the Farman plane and also that of Léon Delagrange were approximate copies of the Wright plane but that the Wright machine “seems more solid, more controllable, and more scientific.”

Two days after that first demonstration, on August 10, Wilbur made two more short flights, the first one a figure eight, and the other, three complete circles. He flew on August 11 for 3 minutes 43 seconds; the next day, 6 minutes 56 seconds; and on August 13, 8 minutes 13.2 seconds. This time he did seven wide “orbes,” as the French described them. In landing that day Wilbur broke the left wing of his plane and repairs kept him from flying until August 21. He took time out on August 24 to attend an agricultural fair where reporters observed that he seemed much interested in pigs and cattle and, as one paper expressed it, “talked much more freely about them than about aviation.”

After those first few flights, the army officer in charge of the artillery testing grounds at Auvours let it be known that the military people at Paris would be proud to have Wilbur Wright’s further demonstrations carried on there. As the military field was larger than that at Hunaudières, Wilbur was glad to make the change. The Hunaudières hangar—which Wilbur persisted in calling the “shed”—was torn down and rebuilt within twenty-four hours at Auvours. As the two fields were only about ten miles apart, Wilbur could have flown the plane to the new location; but with so much at stake he was taking no chances. The plane was placed longitudinally on two wheels fastened behind Léon Bollée’s automobile and towed to the Auvours field without removing the wings. Within a month after setting up operations at Auvours, Wilbur was flying many times the distance between the two fields.

All parts of France were now flooded with souvenir post cards bearing pictures of Wilbur or of his plane in flight. And the French people gave him all the hero-worship of which they were capable. There was talk of a public subscription for a testimonial to him. When the French ambassador to the United States reached New York a short time later he declared that Wilbur Wright was accepted as the biggest man in France. It wasn’t alone his achievements in the air that won the people, but also his modesty, decency, and intelligence. The French papers made enthusiastic comment on the fact that in conversation he seemed to be exceptionally well informed not only about scientific work, but also on art, literature, medicine, and affairs of the world.

Newspapermen liked Wilbur because he always made it plain that they were welcome. They probably liked him all the more because, as a joke, he usually put them at manual work, to fetch tools, or help drag the plane in and out of the hangar.

Those who had access to the hangar were impressed by the orderliness of the place. Wilbur’s canvas cot was hauled up by ropes toward the roof during the day, and the space where he slept was divided from another section of the building by a low partition made of wood from packing cases. Wilbur explained that one room was his bedroom, the other his dining-room. Another trait that appealed to the French was Wilbur’s punctuality at all appointments. No one ever had to wait even a minute on him.

Nothing Wilbur was overheard to say by French journalists seemed too trivial to be recorded. One day he said “fine” to an assistant, by way of commendation, and the next day a Paris paper explained that Wilbur meant “C’est beau.” “Boys, let’s fix these ropes” was promptly translated as “Allons, jeunes gens, allez disposer les cordes.”

Wilbur was flooded with letters of all kinds. Some were from scientists seeking information, and hundreds came from women who desired to make his acquaintance. He tried his best to answer all sensible questions from scientists; the others went into the stove. He was equally considerate of scientific-minded people—including those who might be considered rivals in aviation—who came in person. To all who had real interest he patiently explained any detail of his machine. But he was capable of quiet sarcasm toward the ill-informed who started to enlighten him about aerodynamics.

It now became the fashionable thing for Parisians to take a train down to Le Mans and drive from there to the Champ d’Auvours to see Wilbur fly. Amusing episodes grew out of that. Since the flights were not often announced in advance, those who made the sight-seeing trip had to take their chances. But some of the callers felt almost a personal affront if Wilbur made no flight on the day they happened to be there. One American society woman living in Paris was bitterly resentful when she was told that Monsieur Wright was taking a nap and therefore would not fly that afternoon. “The idea,” said she, petulantly, “of his being asleep when I came all the way down here to see him in the air!”

Cabmen at Le Mans found the sudden influx of visitors so profitable that they tried to make the most of it and encouraged people who had been disappointed to come again the next day. They would always say: “He is sure to fly tomorrow. We have it on good authority.”

So grateful to Wilbur were members of the “Le Mans-Auvours Aeroplane Bus Service” for the profitable trade he had created, that they wanted to give a banquet in his honor.

News of Wilbur’s flights at Le Mans naturally caused talk in England. Members of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain, one after another, went to Le Mans in doubt about the flights being as wonderful as reported, but returned convinced that the age of practical flying-machines had come.

One of the first to go from England to investigate was Griffith Brewer, who had been making balloon ascensions since 1891. Half apologetically, lest he be thought over-credulous, he confided to an old associate of his in ballooning, Charles S. Rolls, founder of the Rolls-Royce motor car firm, that he was going to France to see Wilbur Wright fly. Rolls laughed and said he had just returned from seeing him fly.

On his arrival at Le Mans, Brewer walked to the shed at the edge of the field. Opposite the shed, in the middle of the field, was Wilbur Wright tuning up his machine. As a crowd was about Wilbur, Brewer hesitated to add to it, but sat down by the shed to smoke his pipe. When a mechanic came from the machine over to the shed for a tool, Brewer handed him a calling card with the request that he give it to Wilbur Wright. Wilbur glanced at the card, nodded to Brewer, and went on with his work. There was no flight, but it was some time before Wilbur returned to the shed; and as he stayed inside for what seemed a long time, Brewer began to think there might be an indefinite wait. Then Wilbur came out, putting on his coat, and said: “Now, Mr. Brewer, we’ll go and have some dinner.”

They went to Madame Pollet’s inn near by for a simple meal and Brewer, eager though he was to discuss aviation, wondered if the inventor might not appreciate a rest from the subject of flying. He therefore talked to him of affairs in America. Wilbur liked that, and they formed a friendship.

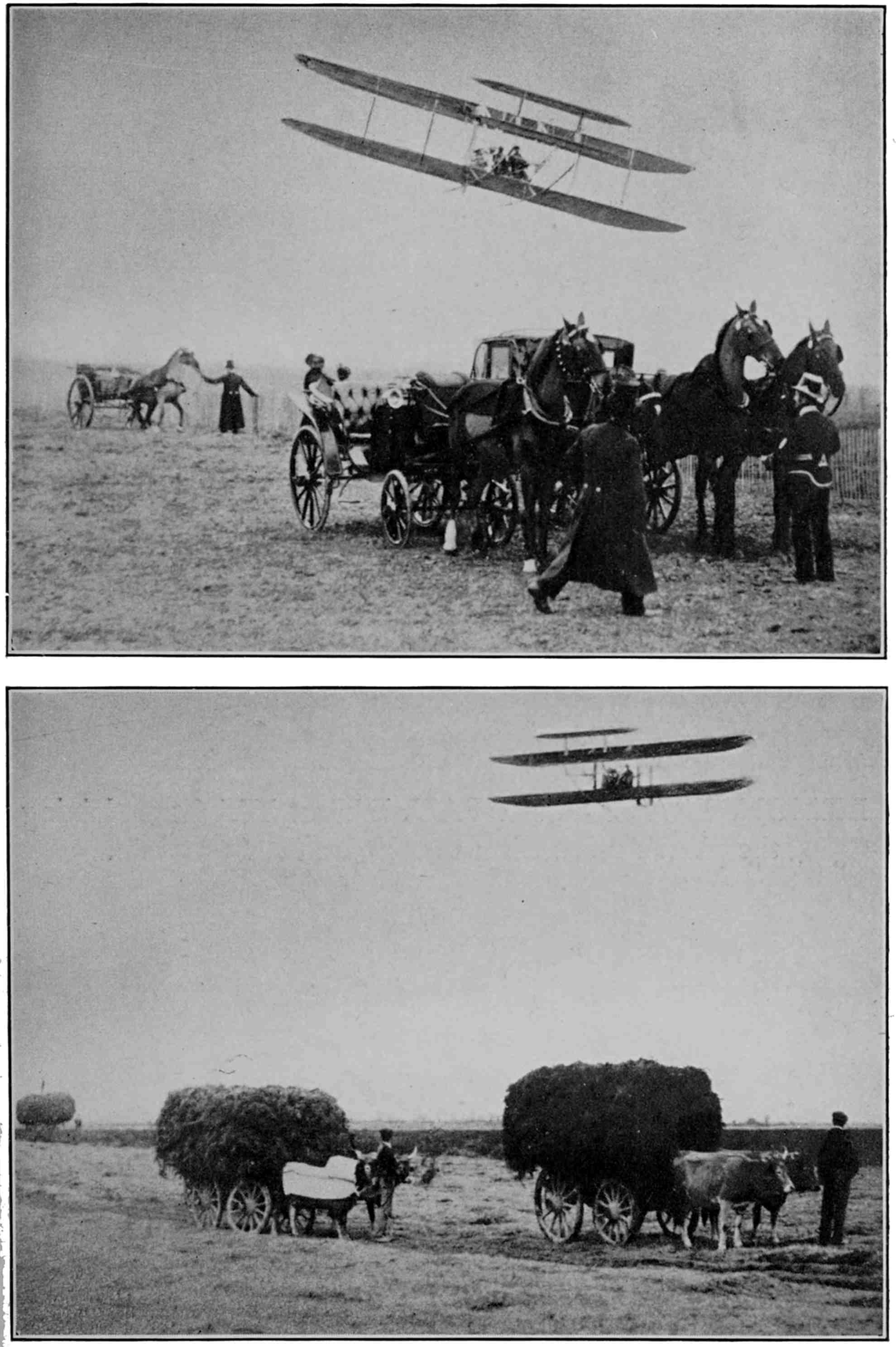

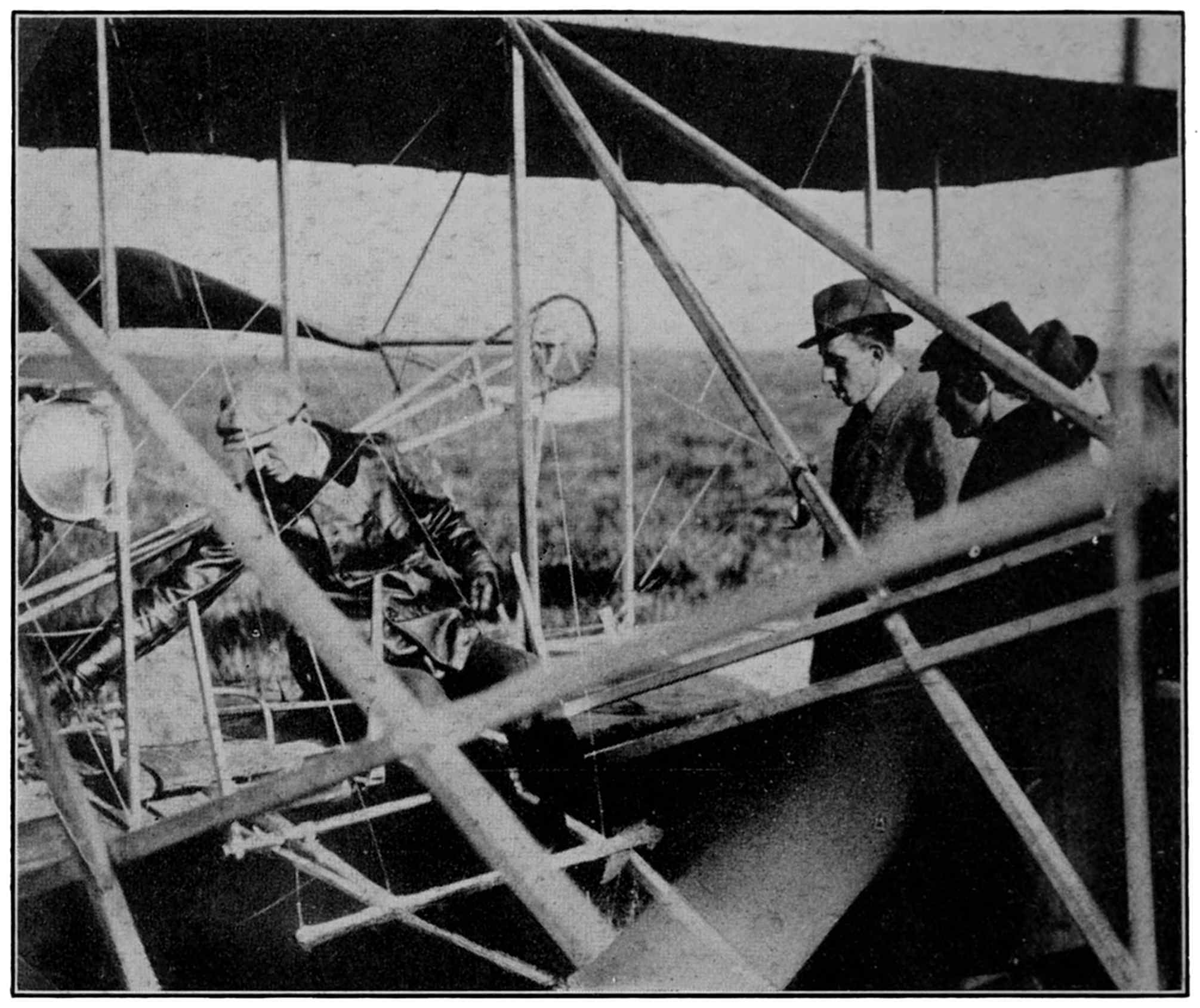

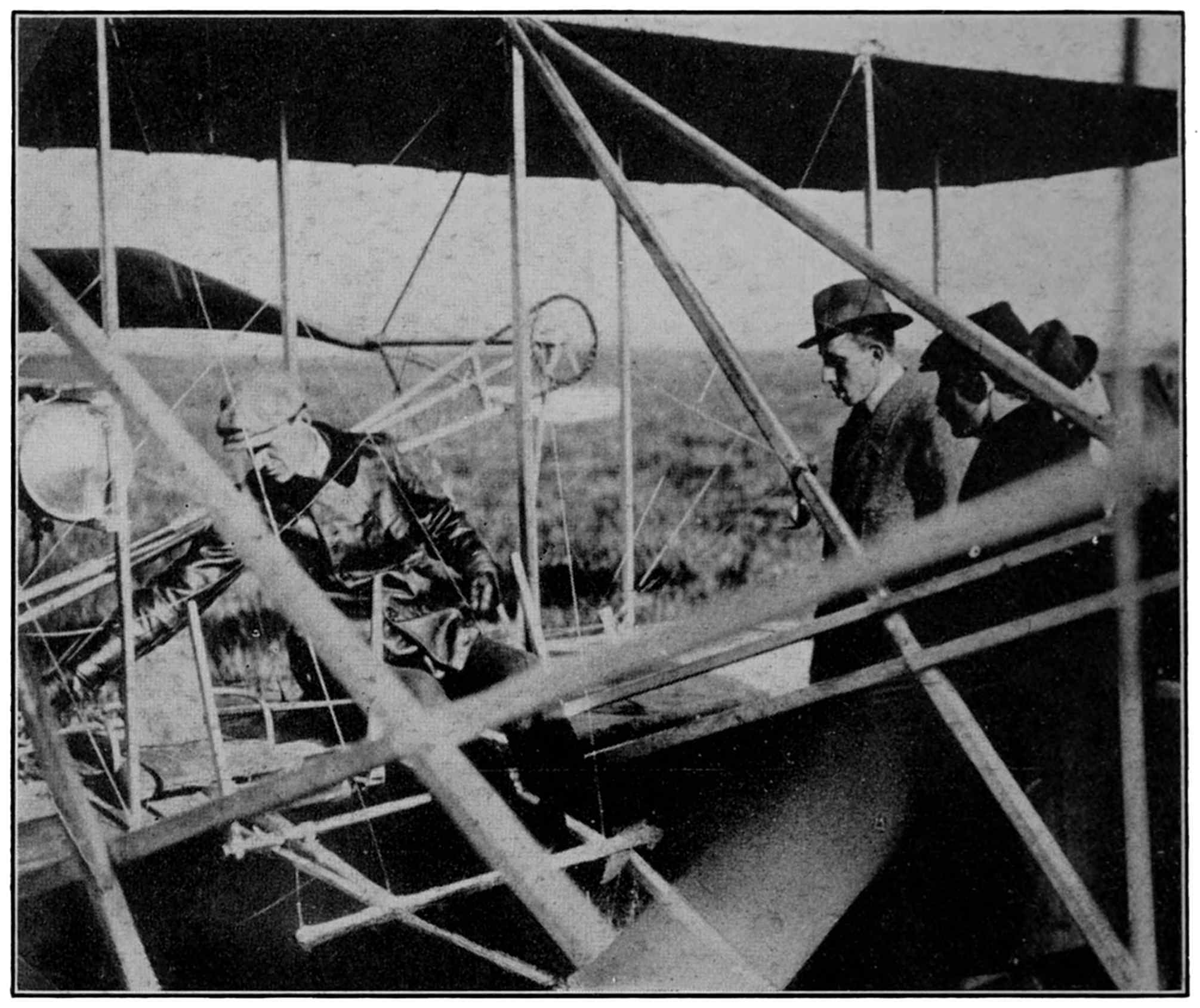

THE OLD AND THE NEW IN TRANSPORTATION. Two views of the Wright plane in flight at Pau, France, in 1909.

On September 12, Wilbur was guest of honor at a dinner in Paris given by the Aéro Club of the Sarthe (the governmental department in which Le Mans was located). It was understood that he would not be expected to make a speech, but Baron d’Estournelles, member of the Senate from Le Mans, who presided, did nevertheless call upon him. Wilbur then, in justification of his unwillingness to say much, made a remark that became famous.

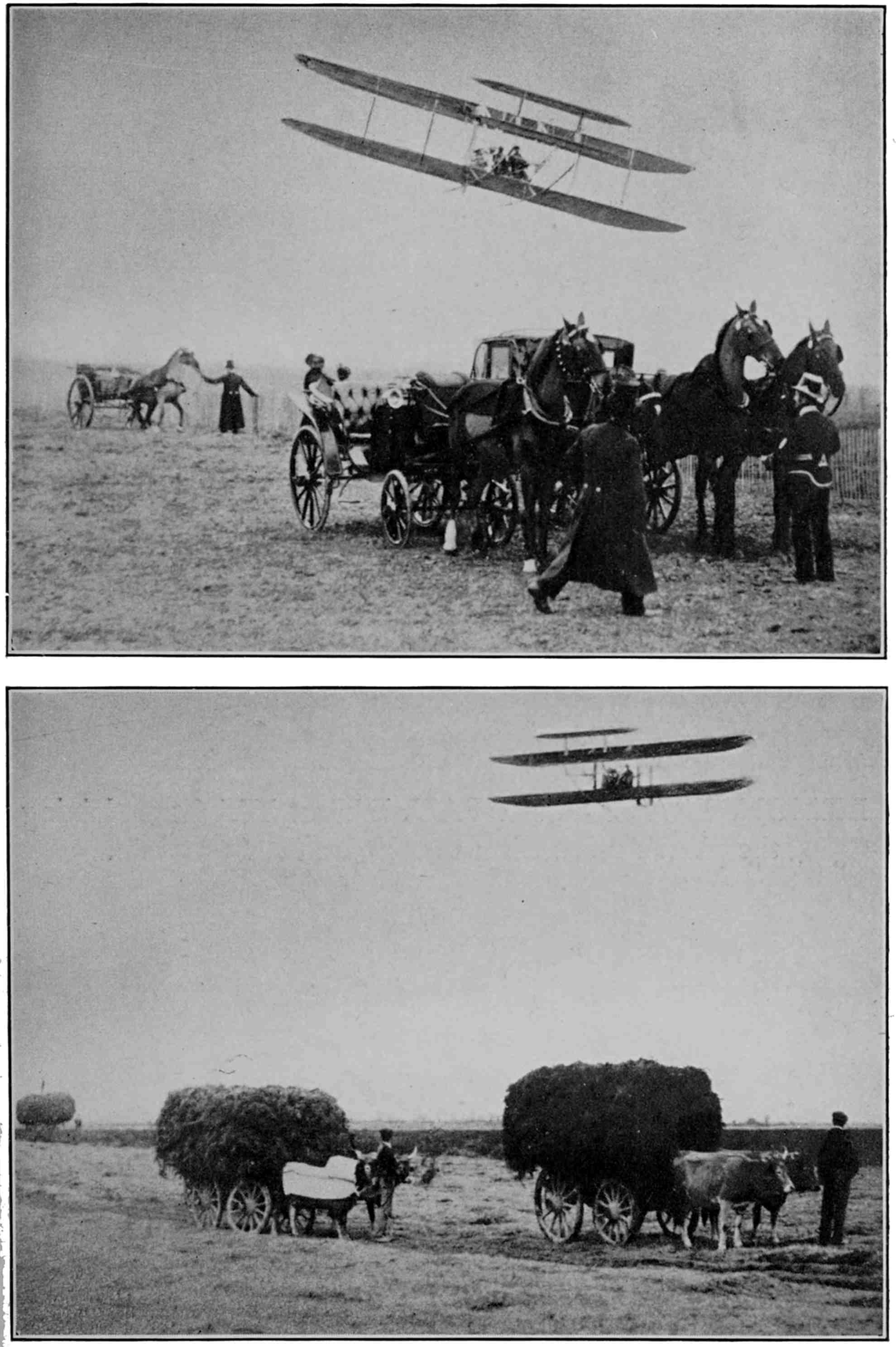

DEMONSTRATION AT PAU. Wilbur Wright explaining the plane’s mechanism to Alfonso XIII of Spain.

“I know of only one bird, the parrot, that talks,” he was quoted as saying, “and it can’t fly very high.”

For the first time in France, Wilbur, on September 16, took up a passenger, a young French balloonist, Ernest Zens.

Two days later, in the early morning of September 18, as he was about to make a flight, Wilbur got word about the tragic accident at Fort Myer the day before, when Lieutenant Selfridge was killed and Orville Wright injured, it was not yet known how seriously.

Within a few hours cables brought word that Orville would recover, and Wilbur was able to fly again the next day. Two days later, on September 21, he flew about forty miles, in 1 hour 31 minutes 25.4 seconds. News of that proved to be better medicine for Orville, in Washington, than anything the attending physician could do.

Many passengers now made short flights with Wilbur. They included, on October 3, Mr. Dickin, of the Paris edition of the New York Herald, and Franz Reichel, of the Paris Figaro. Reichel was so enthusiastic over his flight of nearly an hour, that on landing he threw his arms about Wilbur.

Léon Bollée had his first flight on October 5, and the next day Arnold Fordyce flew with Wilbur for 1 hour 4 minutes and 26 seconds, the longest flight yet made in an airplane with a passenger.

Now that Wilbur was carrying much weight and on longer flights, the Paris edition of the New York Herald became impressed with future possibilities for carrying mail by plane. It predicted that the time might come when there would be special stamps for “aeroplane delivery.”

A witness to several of these flights in early October was Major B. F. S. Baden-Powell, President of the Aeronautical Society of Great Britain (and a brother of the founder of the Boy Scouts). He was so impressed by what he saw that he sounded a warning to his fellow countrymen. Major Baden-Powell was quoted as follows in the Paris edition of the New York Herald on October 6, 1908:

If only some of our people in England could see or imagine what Mr. Wright is now doing I am certain it would give them a terrible shock. A conquest of the air by any nation means more than the average man is willing to admit or even think about. That Wilbur Wright is in possession of a power which controls the fate of nations is beyond dispute.

Hart O. Berg, on October 7, went for a flight, his first, lasting three minutes and twenty-four seconds. Immediately afterward Wilbur took Mrs. Berg for a flight, of two minutes, three seconds, the first ever made anywhere in the world by a woman. (One or two women were reported to have been in planes that made short hops, but Mrs. Berg was certainly the first woman to participate in a real flight.)

Berg tied a rope about the lower part of his wife’s skirt to keep it from blowing. A Paris dressmaker who was among the spectators noted that Mrs. Berg could hardly walk, after landing, with that rope above her ankles. There, thought the couturière, was a suggestion for something fashionable. A costume with skirt thus drawn between the ankles and the knees to make natural locomotion difficult should appeal to any customers who happened to be both stupid and rich. Thus was born the “hobble skirt” which, for a short time, was considered “smart.”

The next day, October 8, her royal highness, Margherita, the dowager queen of Italy, who was touring France, came to see a flight.

“You have let me witness the most astonishing spectacle I have ever seen,” was her comment to Wilbur Wright.

On that same October 8, Griffith Brewer, making his second visit to Le Mans, won the distinction of being the first Englishman ever to fly. He was followed almost immediately by three other British Aeronautical Society members, C. S. Rolls, F. H. Butler, and Major Baden-Powell.

One of the Englishmen remarked: “How decent it is of Wilbur Wright never to accept a fee for any of these flights, when there are scores of persons who would gladly pay hundreds of pounds for the privilege.”

Wilbur continued until the end of the year to take up passengers at Auvours. Among them, on October 10, was M. Painlevé, of the French Institute. As they were taking off, M. Painlevé gaily waved his hand at the crowd and in so doing accidentally pulled a rope overhead that Wilbur used for stopping the engine. After another start, the flight lasted one hour, nine minutes, forty-five seconds, and covered forty-six miles, a world record for both duration and distance for an airplane carrying two persons. Two other women besides Mrs. Berg had short flights—Mesdames Léon Bollée and Lazare Weiller. A passenger on October 24 was Dr. Pirelli, leading tire manufacturer in Italy. Later, in November, F. S. Lahm, one of the first in Europe to believe the Wrights had flown, had his first ride in a plane. Among the distinguished people who made passenger flights were two destined to die by assassins’ bullets: Paul Doumer, member of the French parliament, afterward President of France; and Louis Barthou, Minister of Public Works and Aerial Communications, afterward Premier.

Under the terms of the contract between the Wrights and the newly formed French company, one of the Wright brothers was to train three pilots. Wilbur began this training at Auvours. The students were Count Charles de Lambert, Paul Tissandier, and Captain Lucas de Girardville. Both Tissandier and de Lambert had made flights as passengers on September 28, but did not begin their training until later. Captain Lucas de Girardville went up as a passenger for the first time on October 12. The first to receive a lesson at piloting was Count de Lambert on October 28.

The Aéro Club of France had offered a prize of 2,500 francs for an altitude of twenty-five meters. But there was a “catch” to that offer. A little clique in the Aéro Club, a bit over-chauvinistic, wanted a native experimenter to win, and that was why the altitude to be attained was fairly low. It was stipulated that anyone competing for the prize must start without use of derrick or catapult. The French experimenters had wheels on their machines and could get as long a start as necessary before leaving the ground. But the Wright machine, designed for the rough, sandy ground at Kitty Hawk, and the somewhat bumpy Huffman field, still had skids instead of wheels. Thus the rules for the contest seemed to be aimed to prevent Wilbur Wright from winning the prize. Members of the Aéro Club of the Sarthe thought their compatriots in the Aéro Club of France were being unsportsmanlike, and they offered a prize of 1,000 francs for an altitude record of thirty meters. Wilbur won it on November 13. In doing so he went three times as high as required, reaching an altitude of ninety meters. Then Wilbur decided that he might as well win the prize of the Aéro Club of France, and do so on their own terms. He arranged for a longer starting track than usual, and, five days after taking the prize for thirty meters, he started without the use of derrick or catapult and won the prize for twenty-five meters. To the delight of his friends in the Aéro Club of the Sarthe, he purposely did not throw in much altitude for good measure and went only high enough to clear safely the captive balloon that showed the height required.

On December 16, Wilbur astounded the spectators by shutting off the motor at an altitude of about 200 feet and volplaning slowly down. And on December 18, he flew for 1 hour 54 minutes 53.4 seconds. Later that same day he won another prize offered by the Aéro Club of the Sarthe for an altitude of a hundred meters. Wilbur went ten meters higher than required. This was a new world’s record for altitude. Then on December 31, the last day he ever flew at Auvours, he made what was then an almost incredible record of staying continuously in the air 2 hours 20 minutes 23.2 seconds. For this feat he won the Michelin award of $4,000, or 20,000 francs.

As the weather at Le Mans was no longer ideal for flying, it was necessary to seek a warmer climate, and at the suggestion of Paul Tissandier, Wilbur decided to go to Pau, a beautiful winter resort city of 35,000, at the edge of the Pyrenees. The city of Pau provided a field and a hangar.13

At about the same time, Orville Wright, now rapidly recuperating from his injuries at Fort Myer, arrived in Paris with their sister, Katharine, for a reunion with Wilbur. Then Wilbur went on down to Pau, and his brother and sister joined him there a week or two later. En route to Pau, their train met with an accident near the town of Dax, in which two persons were killed. The Wrights escaped injury, but Orville was a bit startled for another reason. When the crash came, his mattress tipped up on one side at the same time that his watch, pocketbook and other articles slid off a stand or shelf beside the bed. His valuables thus got themselves hid beneath the mattress and, until he chanced to find them, it looked as if he had been robbed.

As at Le Mans, Wilbur lived at the hangar, where he had a French cook the hospitable Mayor de Lassence, of Pau, had selected. His brother and sister lived at the Hotel Gassion, not far from the famous old château where Henry IV was born, and within a short stroll from the Place near the center of the city that affords what Lamartine has called the finest land view in all the world. The Wrights were not long in discovering that life here should be ideal. Wilbur’s French cook proved to be competent enough at preparing regional and other choice dishes—though Katharine Wright did not think he had quite the best technique with a broom for keeping the quarters clean. A London newspaper photographer gave Orville a photograph of his sister demonstrating to that Frenchman how to handle a broom.

By coming to Pau the Wrights had unintentionally played a joke on James Gordon Bennett, owner of the New York Herald and Paris Herald. A few years previously, when Bennett was spending the winter there, he had a tally-ho party and someone in the party had attracted the attention of the police. The episode was reported in local newspapers. Bennett was so indignant that he laid down a rule for both his papers to say as little as possible about Pau. But now, with Wilbur Wright flying there, the town could hardly be ignored. Pau date lines were again frequent in the Bennett papers.

Wilbur did not attempt any new records at Pau, but devoted most of his time to teaching the young pilots for the French Wright company.

Count Charles de Lambert continued his training, and his wife, almost equally enthusiastic over aviation, made a passenger flight. Another woman to make a flight at Pau was Katharine Wright herself. It was her first trip in a plane, though, as she laughingly remarked, she had heard plenty about aviation.

An American multi-millionaire from Philadelphia, spending some time at Pau, announced, with the self-confidence money sometimes gives, that he intended to make a flight with Wilbur. When told that Wilbur was not taking up any passengers, he replied: “Oh, I daresay that can be arranged.”

“I’d like to be around when you do the arranging, just to see how it’s done,” observed Lord Northcliffe, owner of the London Daily Mail, who had recently arrived and become acquainted with the Wrights. The American went away without having had his ride.

In February, King Alfonso of Spain came to Pau with his entourage, and the Wrights were formally presented to him at the field. “An honor and a pleasure to meet you,” said the king.

Alfonso showed more boyish enthusiasm about the plane than almost anyone. He was eager to fly, but both his queen and his cabinet had exacted a promise that he would not. However, he climbed aboard the plane and sat there for a long time fascinated while Wilbur painstakingly explained every detail.

A little later, on March 17, still another king arrived. Edward VII of England came by automobile with his suite from near-by Biarritz. The presentation of the brothers and their sister was made at the field and Edward showed his customary graciousness. He did not seek any technical details about the machine, but was much interested in seeing the flights themselves and in meeting the Wrights.

It was during the stay of King Edward that Miss Katharine Wright made her second trip in an airplane.

Other famous personages continued to come to Pau, among them Lord Arthur Balfour, former Prime Minister of England. Sometimes when Wilbur was preparing for a flight, visitors would pull on the rope that raised the weights on the launching derrick. Balfour insisted that he must not be denied this privilege of “taking part in a miracle” and did his share of yanking at the rope. Another man who shared in handling the rope that day was a young English duke.

“I’m so glad that young man is helping with the rope,” said Lord Northcliffe to Orville Wright, with a motion of his head toward the duke, “for I’m sure it is the only useful thing he has ever done in his life.”

Northcliffe, after his meeting with the Wrights at Pau, became one of their most enthusiastic supporters in England.

Long afterward, he publicly made this comment:

“I never knew more simple, unaffected people than Wilbur, Orville, and Katharine. After the Wrights had been in Europe a few weeks they became world heroes, and when they went to Pau their demonstrations were visited by thousands of people from all parts of Europe—by kings and lesser men, but I don’t think the excitement and interest produced by their extraordinary feat had any effect on them at all.”