XVII

IN AVIATION BUSINESS

AFTER companies to manufacture the Wright brothers’ invention had been organized in France and Germany, and a plane had been sold in Italy, it might have been expected that important business people in the United States would see commercial possibilities in the Wright patents. The inventors had, indeed, received offers. One proposal had come from two brothers, in Detroit, influential stockholders in the Packard Automobile Company, Russell A. and Frederick M. Alger—who some time before had been the first in the United States to order a Wright machine for private use. But the first American company to manufacture the plane was promoted by a mere youngster.

That was Clinton R. Peterkin. He was barely twenty-four and looked even younger. Only a year or two previously he had been with J. P. Morgan & Company as “office boy”—a job he had taken at the age of fifteen. But he had intelligently made the most of his opportunities by spending all the time he could in the firm’s inner rooms, and had learned something of how new business enterprises were started.

Now, recently returned from a stay in the West because of ill health, Peterkin wished to be a promoter, and he wondered if the Wright brothers would agree to the formation of a flying-machine company. By chance he learned that Wilbur Wright was spending a few days at the Park Avenue Hotel in New York, and in October, 1909, he went to see him.

Wilbur was approachable enough and received Peterkin in a friendly way, though he didn’t seem to set too much store by the young man’s proposals. In reply to questions, Wilbur said that he and his brother would not care to have a company formed unless those in it were men of consequence. They would want names that carried weight. Then Peterkin spoke of knowing J. P. Morgan, whom he might be able to interest.

Without making any kind of agreement or promise, Wilbur told him he could go ahead and see what he could do—doubtless assuming that he would soon become discouraged. But Peterkin saw J. P. Morgan who told him he would take stock and that he would subscribe also for his friend Judge Elbert H. Gary, head of the United States Steel Corporation.

After seeing Morgan, Peterkin was enthusiastically telling of his project to a distant relative of his, a member of a law firm with offices in the financial district. The senior partner in that law firm, DeLancey Nicoll, chanced to overhear what Peterkin was saying and grew interested. He suggested that perhaps he might be of help. That was a good piece of luck for Peterkin. He could hardly have found a better ally, for DeLancey Nicoll had an exceptionally wide and intimate acquaintance among men in the world of finance. All he needed to do to interest some of his friends was to call them on the telephone.

In a surprisingly short time, an impressive list of moneyed men were enrolled as subscribers in the proposed flying-machine company. A number of them were prominent in the field of transportation. The list included Cornelius Vanderbilt, August Belmont, Howard Gould, Theodore P. Shonts, Allan A. Ryan, Mortimer F. Plant, Andrew Freedman, and E. J. Berwind. Shonts was president of the New York Interborough subway. Ryan, a son of Thomas F. Ryan, was a director of the Bethlehem Steel Corporation. Plant was chairman of the Board of Directors of the Southern Express Company, and Vice President of the Chicago, Indianapolis & Louisville Railroad. Berwind, as President of the Berwind-White Coal Mining Company, had accumulated a great fortune from coal contracts with big steamship lines. Freedman had made his money originally as a sports promoter and then in various financial operations. (He later provided funds for founding the Andrew Freedman Home in New York.)

The Wrights wanted to have in the company their friends Robert J. Collier, publisher of Collier’s Weekly, and the two Alger brothers of Detroit. Those names were promptly added.

But the names of J. P. Morgan and E. H. Gary were not in the final list of stockholders. The truth was that some of the others in the proposed company did not want Morgan with them because they believed—probably correctly—that he would dominate the company; that where he sat would be the head of the table. One of them phoned to Morgan that the stock was oversubscribed. When he thus got strong hints that his participation was not too eagerly desired, Morgan promptly withdrew his offer to take stock for himself and Gary.

On November 22, 1909, only about a month after Peterkin’s first talk with Wilbur, The Wright Co. was incorporated. The capital stock represented a paid-in value of $200,000. In payment for all rights to their patents in the United States, the Wright brothers received stock and cash, besides a provision for ten per cent royalty on all planes sold; and The Wright Co. would thenceforth bear the expense of prosecuting all suits against patent infringers.

From the Wright brothers’ point of view, the one fly in the ointment was that they now found themselves more involved than ever before in business affairs. It had been their dream to be entirely out of business and able to give their whole time to scientific research.

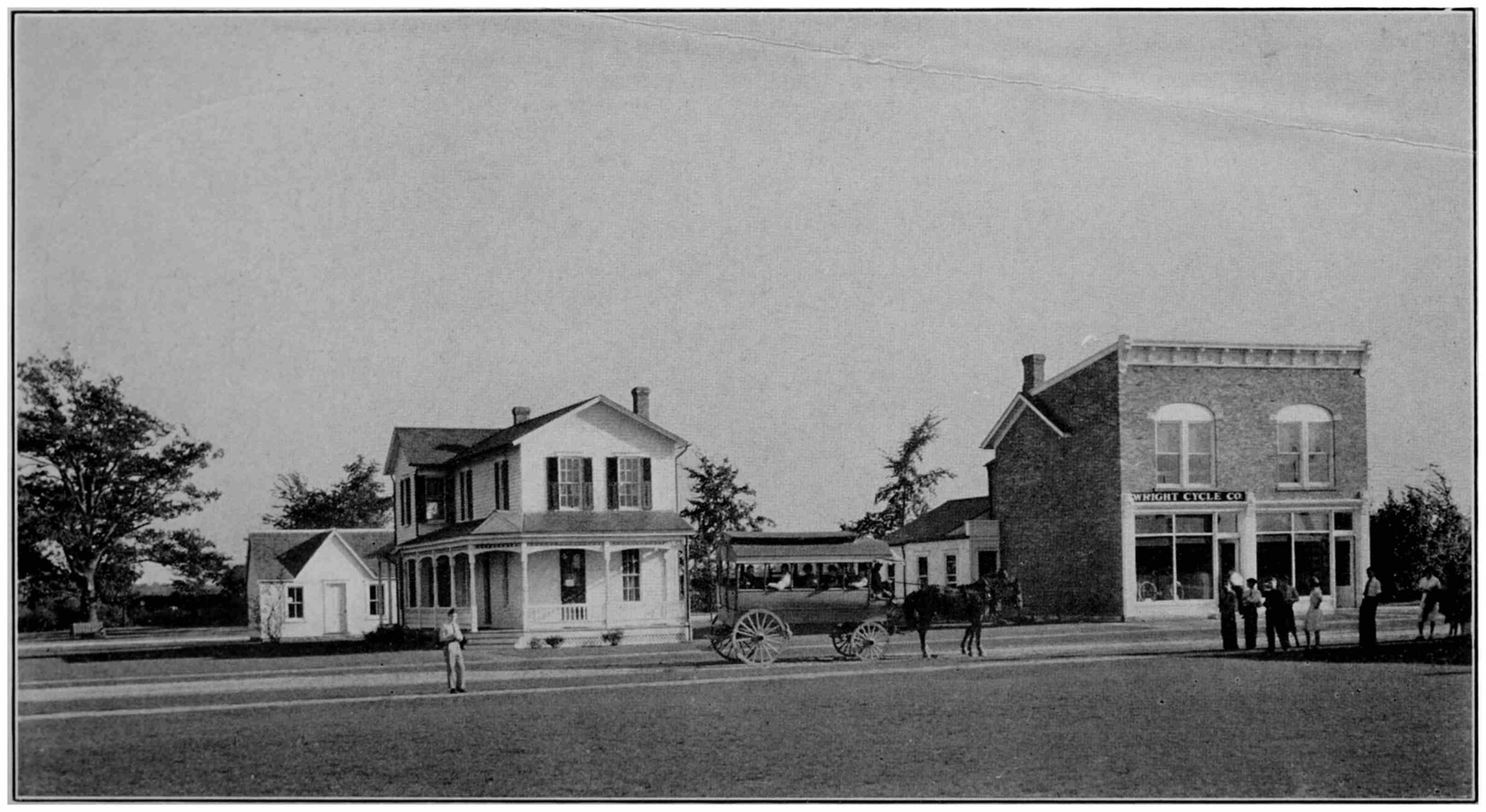

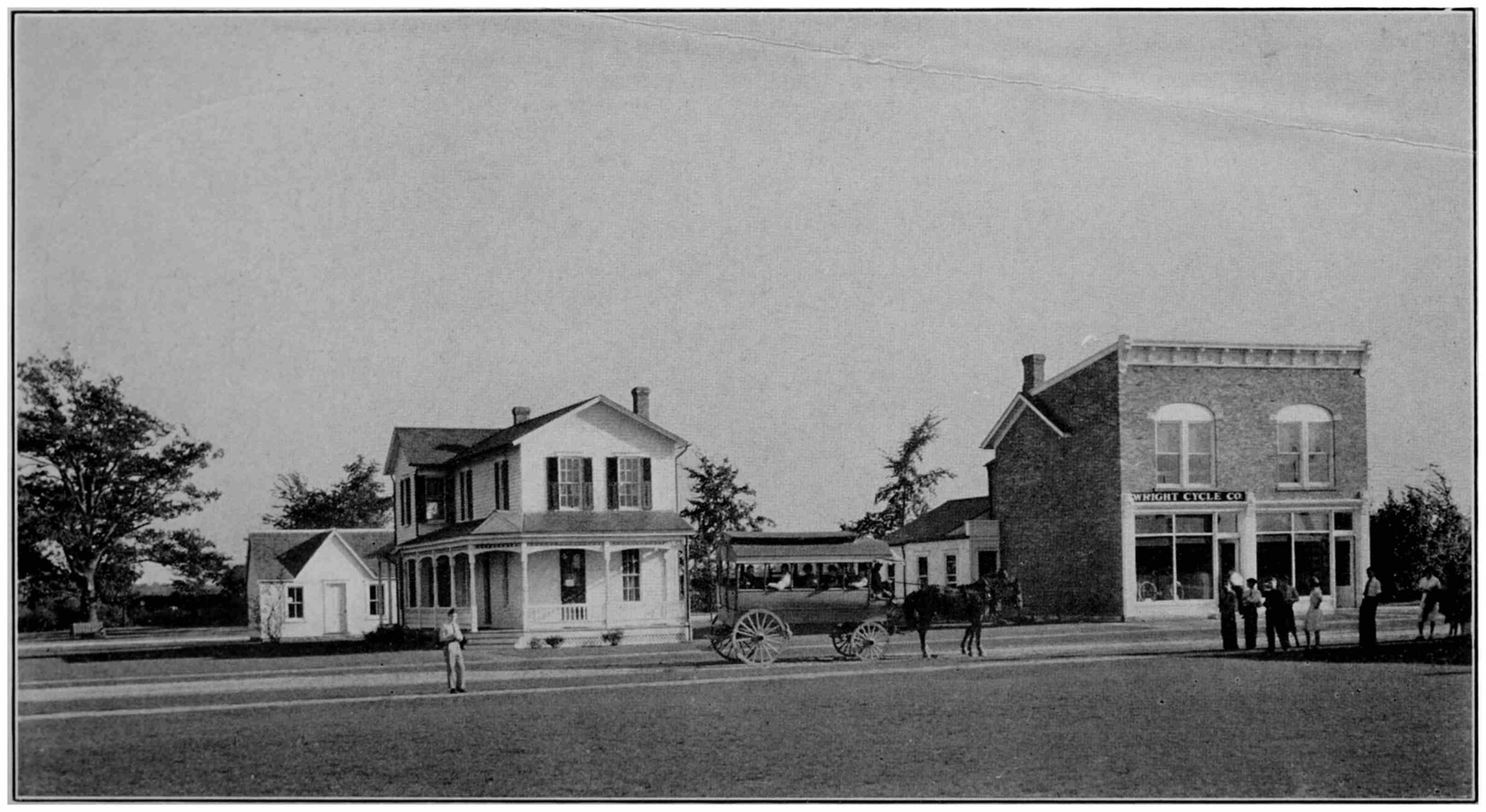

The company opened impressive offices in the Night and Day Bank Building, 527 Fifth Avenue, New York, but the factory would be in Dayton. In January, 1910, Frank Russell, a cousin of the Algers, who had been appointed factory manager, arrived in Dayton and went to see the Wrights at their office over the old bicycle shop. As the brothers had no desk space to offer him, they suggested a room at the rear of a plumbing shop down the street where he might make temporary headquarters. According to Russell, Wilbur Wright came there a day or two later carrying a basket filled with letters, directed to The Wright Co., that had been accumulating.

“I don’t know what you’ll want to do about these,” Russell has reported Wilbur as jokingly saying; “maybe they should be opened. But of course if you open a letter, there’s always the danger that you may decide to answer it, and then you’re apt to find yourself involved in a long correspondence.”

At first The Wright Co. rented floor space in a factory building, but almost immediately the company started to build a modern factory of its own, and it was ready for use by November, 1910. Within a short time after the company started operations in its rented space it had a force of employees at mechanical work and was able to produce about two airplanes a month.

The Wrights well knew that the time was not yet for the company to operate profitably by selling planes for private use. Their main opportunity to show a good return on the capital invested would be from public exhibitions. Relatively few people in the United States had yet seen an airplane in flight and crowds would flock to behold this new miracle—still, in 1910, almost incredible.

As soon as they decided to give public exhibitions, the Wrights got in touch with another pioneer of the air, Roy Knabenshue, a young man from Toledo, who had been making balloon flights since his early teens, and was the first in the United States to have piloted a steerable balloon. They had previously become acquainted with Knabenshue. Because of his curiosity over anything pertaining to aerial navigation, he had once subscribed to a press-clipping bureau which sent him anything found in the papers about aeronautics; and in this way he had been able to read an occasional news item about the two Dayton men said to have flown. With a fairly irresistible impish grin, Knabenshue never had much trouble making new acquaintances, and he decided to call upon the Wrights.

That was before the Wright flights at Fort Myer and in France, and the brothers were not then interested when Knabenshue suggested that they sell him planes for exhibitions.

“Well,” he said, “I have been making airship flights at the big state fairs, besides promoting public exhibitions, and I know how to make the proper contacts. You may have heard about my flights in a small dirigible at the St. Louis World’s Fair. If you ever decide to give exhibitions, just let me know.”

Though exhibitions had been farthest from the Wrights’ thoughts at the time of that first meeting with Knabenshue, now the situation was different. Roy Knabenshue would probably be the very man they needed. They sent a telegram to him and he received it at Los Angeles. He wired back that he would see them as soon as he returned to Ohio. This he did soon afterward. The result of their conversation was that Roy took charge of the work of arranging for public flights. He had need of a competent secretary and an intelligent young woman, Miss Mabel Beck, came to take the job. This was her first employment and she seemed a bit ill at ease, lest her work might not be satisfactory; but almost immediately she became an extraordinarily good assistant—so good, in fact, that Wilbur Wright afterward selected her to work with him in connection with suits against patent infringers, and after his death she became secretary to Orville Wright, in which position, at this writing, she still is.

By the time Knabenshue had started planning for public exhibitions, Orville Wright had begun the training of pilots to handle the exhibition planes being built. The weather was still too wintry for flying at Huffman field, now leased by The Wright Co., and it was necessary to find a suitable place in a warmer climate. The field selected was at Montgomery, Alabama. (Today known as Maxwell Field, it is used by the United States Government.)

Shortly after his arrival at Montgomery, early in 1910, Orville Wright had a new experience in the air. While at an altitude of about 1,500 feet he found himself unable to descend, even though the machine was pointed downward as much as seemed safe. Brought up to have faith in the force of gravity, he didn’t know at first what to make of this. For nearly five minutes he stayed there, in a puzzled state of mind bordering on alarm. Later it occurred to him that the machine must have been in a whirlwind of rising air current of unusual diameter, and that doubtless he could have returned quickly to earth if he had first steered horizontally to get away from the rising current.

The first pilot Orville trained was Walter Brookins of Dayton. “Brookie” was a logical candidate for that distinction, for since the age of four he had been a kind of “pet” of Orville’s. After Orville had left Montgomery and returned to Dayton on May 8, Brookins himself became an instructor. He began, at Montgomery, the training of Arch Hoxsey, noted for his personal charm and his gay, immaculate clothes; and also that of Spencer C. Crane.

On his return to Dayton, Orville opened a flying school at the same Huffman field14 the Wright brothers had used for their experiments in 1904–5. Here he trained A. L. Welsh and Duval LaChapelle. When Brookins arrived there from Montgomery, near the end of May, he took on the training of Ralph Johnstone and Frank T. Coffyn, besides completing the training of Hoxsey. Two others trained at the same field later in the year were Phil O. Parmalee and C. O. Turpin.

Orville Wright continued to make frequent flights until 1915, personally testing every new device used on a Wright plane. (He did not make his final flight as a pilot until 1918.) More than one person who witnessed flights at the Huffman field (or at Simms station, as the place was better known) has made comment that it was never difficult to pick Orville Wright from the other flyers, whether he was on the ground or in a plane. Students, and instructors too, would be dressed to the teeth for flying, with special suits, goggles, helmets, gauntlets, and so on; but Orville always wore an ordinary business suit. He might put on a pair of automobile goggles and shift his cap backward, and on cold days he would turn up his coat collar; but otherwise he was dressed as for the street. When he was in the air anyone could recognize who it was—from the smoothness of his flying. And when he wished to test the control and stability of a plane, he would sometimes come down and make figure eights at steep angles with the wing tip maybe not more than a few feet from the grass.

The public was no longer unaware of the significance of the flights at Huffman field. Sightseers began to use every possible pretext to come as close to the planes as possible. One evening as Orville Wright was standing near the hangar, a bystander edged up to him.

“I flew with Orville Wright down at Montgomery,” he declared, “and he told me to make myself at home here.”

Never before having seen Orville, he had mistaken him for an employee.

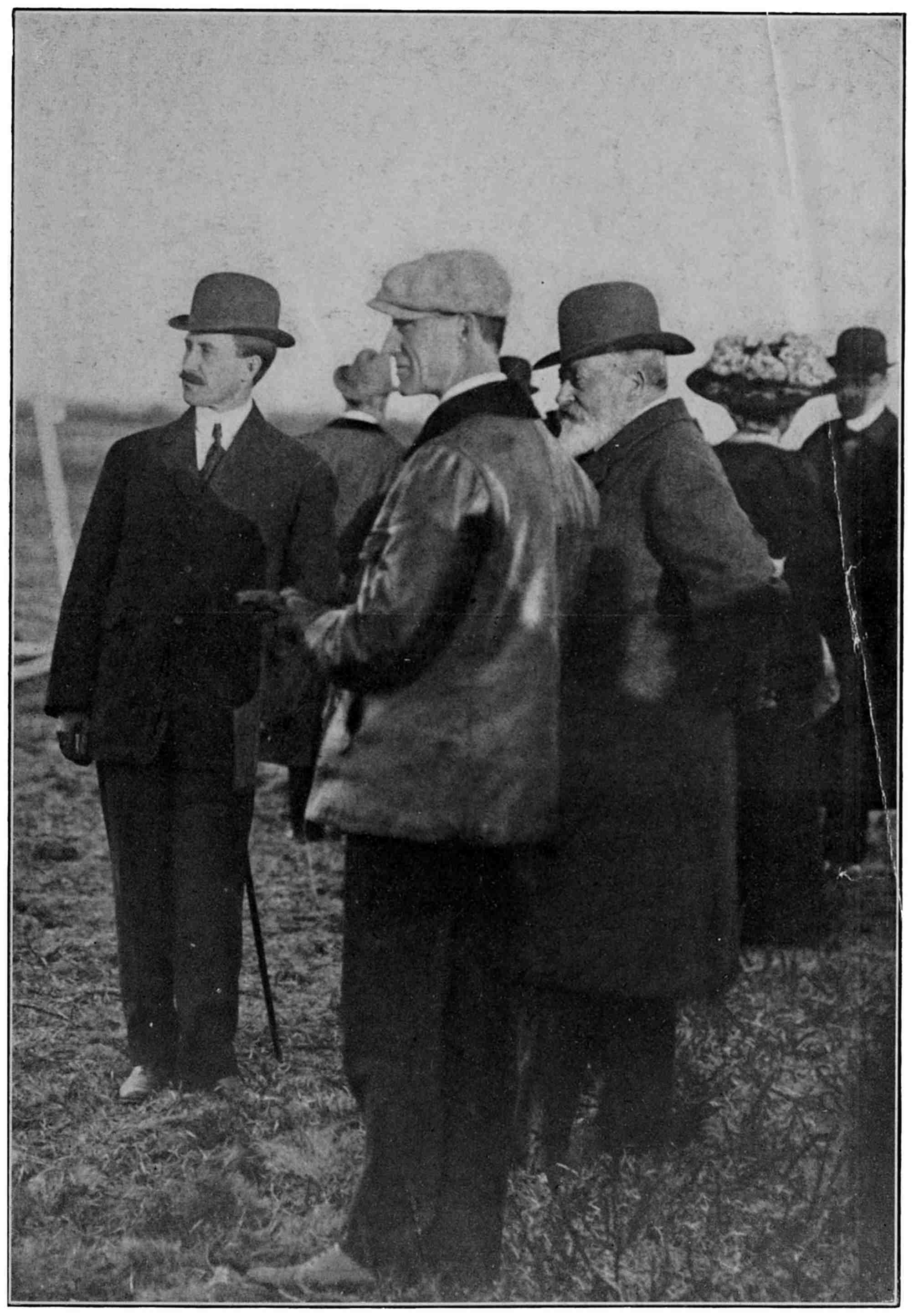

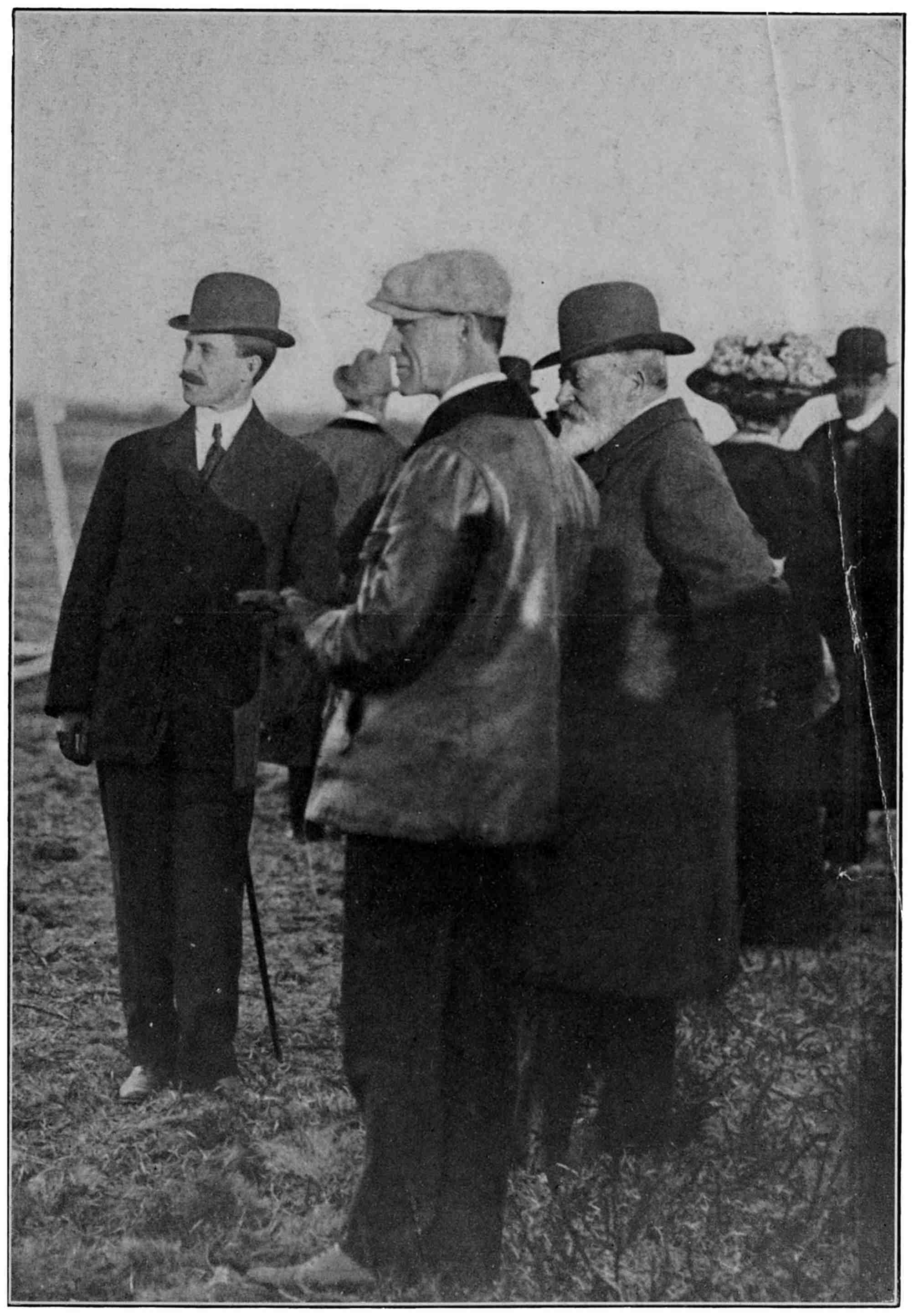

TWO ACES AND KING. Orville Wright, Wilbur Wright, and Edward VII of England at Pau, France, March 17, 1909.

Three flights at Huffman field in May, 1910, were especially noteworthy. A short one by Wilbur—one minute twenty-nine seconds—on May 21, was the first he had made alone since his sensational feats starting from Governors Island. And it was the last flight as a pilot Wilbur ever made. But on May 25 he and Orville flew for a short time together—with Orville piloting—the only occasion when the Wright brothers were both in the air at the same time. Later that same day, Orville took his father, Bishop Milton Wright, then eighty-two years old,15 for his first trip in a flying-machine. They flew for six minutes fifty-five seconds, most of the time at about 350 feet. The only thing that Bishop Wright said while in the air was a request to go “higher, higher.”

The average charge by The Wright Co. for a series of exhibition flights at a county fair or elsewhere was about $5,000 for each plane used. At Indianapolis, the scene of the first exhibition, five planes were used. The weather was not ideal for the Indianapolis event, but the crowd was much impressed. Another early exhibition was at Atlantic City, where, for the first time, wheels were publicly used on a Wright machine for starting and landing.

THE WRIGHT HOME AND SHOP. The original Wright homestead and Wright bicycle shop, brought from Dayton and restored at Greenfield Village, Dearborn, Michigan.

Roy Knabenshue knew from his experience in making public airship exhibitions, that it was not enough to go where a fair or carnival was to be held and suggest airplane flights as a feature. To get all the business possible for his company he must promote exhibition flights in places where no such big outdoor events were yet contemplated. He particularly desired to have flights made in large cities where newspaper reports of the event would attract attention over a large area and aid him in making further bookings. With this in mind he went to Chicago and started inquiries to learn whether public-spirited citizens there would be willing to underwrite a big public demonstration of aviation along the lake front. Several people told him the man he should see was Harold McCormick, one of the controlling stockholders in the wealthy International Harvester Company. He went at once to McCormick’s offices in the Harvester Building. But when he reached the outer office, he discovered that it was not easy to get any farther.

“What was it you wished to see Mr. McCormick about?” asked a secretary.

“I don’t wish to sell him anything,” Roy explained, smiling in a manner that should have won confidence, but didn’t. “Please just say to him that there’s a man here who has an important suggestion for him.”

“But if you’ll tell me what the suggestion is,” the secretary proposed, “then he can let you know if he is interested.”

“No, I’ll tell you what you do,” countered Roy. “Please hand my card to him and let him decide if he wishes to see me.”

The secretary reluctantly took Roy’s card which indicated that he represented The Wright Co. of Dayton, Ohio. A moment later the secretary returned to say that Mr. McCormick was too busy to see anyone.

Roy walked out of the building into Michigan Avenue, discouraged.

“No matter how good an idea you’ve got,” he reflected, “and no matter how much some of these big executives might be interested, you don’t get a chance to tell them about it.”

As he strolled along, his eye chanced to fall on a big sign that read: “Think Of It. The Record-Herald Now One Cent.” Then he remembered that the Chicago Record-Herald, rival of the Tribune in the morning field, had recently reduced its price and was making a big bid for increased circulation. He also recalled that H. H. Kohlsaat, owner of the Record-Herald, had known his father. Using his father’s name for an introduction, he had little difficulty, a half hour later, in gaining access to Kohlsaat’s private office to tell him what was on his mind. The publisher grew interested. Yes, it might be a good idea to have some airplane flights along the lake front and invite the public to see them as guests of the Record-Herald. Before he left the office, Roy had the preliminary arrangements all made.

On the opening day of the big event, when Walter Brookins, as pilot, was about to take off on the first flight, Knabenshue remarked to him: “That corner window on the fourth floor of the Harvester Building is in the office of a man I hope will see what’s going on.”

The next day Knabenshue appeared once again at Harold McCormick’s office in the Harvester Building and presented his business card to the same secretary he had met on his previous visit.

After looking at the card, the secretary, without waiting to consult anyone, said: “Oh, yes, you’re with The Wright Company. I’m sure Mr. McCormick will wish to see you. Just step this way.”

Roy had made this call partly as a kind of practical joke—for the satisfaction of entering an office where he had once been denied. But as a result of the talk he then had with McCormick, it was arranged that a committee of Chicago citizens should sponsor, the next year, another aviation meeting there, to be the biggest thing of the kind ever held.

Meanwhile, on the final day of the 1910 exhibitions at Chicago, Brookins made the first long cross-country flight, 185 miles, to Springfield, Illinois. It was not, however, a non-stop flight. He made one landing in a cornfield, and it was necessary to obtain permission from the farm owner to cut a wide strip across the field to provide space for the plane to take off.

In that same year, 1910, Dayton people saw the first flight over the city itself. Thousands had now seen flights at the Huffman field, Simms station, but no flight had ever been made nearer than eight miles to the home town where successful flying was conceived. The Greater Dayton Association was holding, in September, an industrial exhibit, but it was operating at a loss. Those in charge of the exhibit saw that something would have to be done to arouse interest. Orville Wright was asked if he would start at Simms station, fly to Dayton and circle over the city. He agreed and the newspapers announced the flight for the next day. It was stirring news—even to Katharine Wright. She had started to Oberlin to attend a college meeting, but, when on her arrival there she happened to see a newspaper item about Orville’s flight scheduled for the next day, she hastened home at once.

Another premier event in 1910 was when an airplane for the first time in the world was used for commercial express service. The Morehouse-Martin Co., a department store in Columbus, Ohio, arranged to have a bolt of silk brought from Huffman field to a driving park beyond Columbus. The distance of more than sixty miles was covered at better than a mile a minute, then considered fast airplane speed; and the “express fee” was $5,000, or about $71.42 a pound. But within a day or two the store had a good profit on the transaction, for it sold small pieces of the silk for souvenirs, and the gross returns were more than $6,000.

Then, at Belmont Park, New York, in late October, 1910, Wright planes participated in a great International Aviation Tournament. All other planes taking part were licensed by The Wright Co.

Orville Wright now devoted his time mainly to supervision of engineering at the factory of The Wright Co. Wilbur was kept busy looking after the prosecution of suits against patent infringers and in March, 1911, he went to Europe in connection with suits brought by the Wright company of France. From France he went to Germany and while there called at the home of the widow of Otto Lilienthal to offer his homage to the memory of that pioneer in aviation whose work had been an inspiration to the Wrights.

After Wilbur’s return to America, Orville spent several weeks in October, 1911, at Kitty Hawk, where he went to do some experimenting with an automatic control device and to make soaring flights with a glider. In camp with him were Alec Ogilvie of England, who flew a Wright plane, Orville’s brother Lorin, and Lorin’s ten-year-old boy, “Buster.” On account of the presence of a group of newspapermen who appeared and were at the camp each day during his entire stay at Kitty Hawk, Orville never tested the new automatic device; but before his soaring experiments were over he had made, on October 24, a new record, soaring for nine minutes forty-five seconds. (This was to remain the world’s record until ten years later when it was exceeded in Germany.)

That same year, 1911, The Wright Co. benefited from another aviation record. Cal P. Rodgers, who had received some of his flying training at the Wright School, made—between September 11 and November 5—the first transcontinental airplane trip, from New York to California.

New as their line of business was, The Wright Co. was profitable from the start—especially so during the first year or two when the sight of a flying-machine was still a novelty and contracts for exhibition flights were numerous. (It might have been more profitable if the Wrights had not insisted that no contracts be made to include flights on Sunday.) But inevitably the exhibition part of the business began to taper off—and such profits as might still have come from it were reduced by the persistent illegal competition of patent infringers. More and more, the company’s dealings were with the United States Army and Navy and with private buyers of planes. The first private plane sold had gone to Robert J. Collier, and others seeking the excitement or prestige of owning a plane had been making inquiries. The retail price of a plane was $5,000.

With aviation thus becoming more practical, the Wrights were receiving from their invention a form of reward they had never expected. They would now have wealth, not vast, but enough to enable them to look forward to the time when they might retire and work happily together on scientific research. They were making plans, too, for their new home on a seventeen-acre wooded tract they had named Hawthorn Hill, in the Dayton suburb of Oakwood. But tragic days were ahead. Early in May, shortly after visiting the new home site with other members of the family, Wilbur was taken ill. What at first was assumed to be a minor indisposition proved to be typhoid fever. Worn out from worries over protecting in patent litigation the rights he knew were his and his brother’s, he was not in condition to combat the disease. After an illness of three weeks, despite the best efforts of eminent specialists, early in the morning of Thursday, May 30, 1912, Wilbur Wright died. He was aged only forty-five years and forty-four days.

Messages of condolence and expressions of the world’s loss poured in from two hemispheres, among them those from heads of governments.

Orville Wright succeeded his brother as president of The Wright Co.

In June, 1913, Grover Loening, a young man who had become acquainted with Wilbur at the time of the Hudson-Fulton exhibition flights, came to The Wright Co. as engineer, and then became factory manager. Loening had the distinction of being the first person in the United States to study aeronautical science in a university.

Business affairs had been complicated earlier that year by the fact that Dayton had the worst flood in its history. The Wright factory was not under water but not many of the employees could reach the building. Among the hundreds of houses under water was the Wright home on Hawthorne Street. To Orville a serious part of the loss there was the damage to photographic negatives showing his and Wilbur’s progress toward flight. But the negative of the famous picture of the first power flight was not much harmed.

Accompanied by his sister, Orville made his last trip to Europe in 1913, on business relating to a patent suit in Germany. At about the same time he sanctioned the forming of a Wright company in England. Before Wilbur’s death, there had been opportunities for a company in England, but the brothers had held back because all the offers appeared to be purely stock promotions in which the names of members of the English nobility would appear as sponsors. The British company as finally organized did not make planes itself, but issued licenses for use of the patents. Within a year after it was formed the English company accepted from the British Government a flat payment for all claims against the government, for use of the Wright patents up to that time and during the remainder of the life of the basic patents. Though the amount paid was no trifling sum, the settlement was widely applauded by prominent Englishmen, among them Lord Northcliffe, as showing a generous attitude on the part of the patent owner—about as little as could have been compatible with full recognition of the priority of the Wrights’ invention.

By this time, The Wright Co. had more applications to train student pilots than they could handle. Even a few young women wished to become pilots.

Two capable students, of a somewhat earlier period, destined to go far in aviation, were Thomas D. Milling, later General Milling, of the United States Army Air Corps; and Henry H. Arnold, who during the Second World War was Lieutenant General Arnold, Commanding General of the Army Air Forces and Deputy Chief of Staff for Air.

One unfortunate student pilot, who had begun his training at the Wright School in 1912, later got himself into much trouble. This man became one of the best flyers in the United States. As he had plenty of money he bought a plane of his own, and he used to give free exhibitions at his estate near Philadelphia. In one way or another he did much for aviation. But in 1917, when the United States entered the First World War, that young pilot refused to register in the draft and became notorious as a draft evader. His name? Grover Cleveland Bergdoll. The early Wright plane he had bought is today on exhibition at the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. It is believed to be the only authentic Model B—the first model built by The Wright Co.—in existence.

In 1914, Orville Wright had bought the stock of all other shareholders in The Wright Co., except that of his friend, Robert J. Collier, who, for sentimental reason, wished to retain his interest. Orville’s motive in acquiring almost complete ownership of the company had been as a step toward getting entirely out of business. Both he and Wilbur Wright had agreed to stay with the company for a period of years, not yet expired, and he could not honorably dispose of his own holdings so long as those with whom he had made the agreement were still in the company. But almost immediately after buying the shares of the others, he let it be known that he might be willing to sell his entire interest. To this, Collier, the only other shareholder, agreed. In 1915, Orville received an offer and gave an option to a small group of eastern capitalists that included William Boyce Thompson and Frank Manville, the latter president of the Johns-Manville Co. The deal was closed in October, 1915.

Just after Orville had given his option to the eastern syndicate, Robert J. Collier came to tell him an important piece of news, and to urge him not to sell just yet.

Collier had been having some talks with his friend, the wealthy Harry Payne Whitney, and had urged upon him the idea of doing what Collier thought would be a wonderful piece of philanthropy that would mean much for the future of aviation in the United States. What Collier wanted him to do was to buy the stock of The Wright Co., thus gaining ownership of the Wright patents, and then immediately make the patents free to anyone in the United States who wished to manufacture airplanes.

Whitney was willing to carry out the Collier suggestion. To do so he was also ready to pay more for the stock of The Wright Co. than the syndicate had offered.

But Orville explained to Collier that the option already given was legally drawn and the holders presumably wished to exercise it.

Collier’s daring idea and Whitney’s generous acceptance of it had come just a little too late.