T he behavior of a buyer is influenced by many factors: the price of the

good, the prices of related goods (compliments and substitutes), incomes of

the buyer, the tastes and preferences of the buyer, the period of time and a

variety of other possible variables. The quantity that a buyer is willing and able

to purchase is a function of these variables.

An individual’s demand function for a good (Good X) might be written:

QX = fX(PX, Prelated goods, income (M), preferences, . . . )

•

QX = the quantity of good X

•

PX = the price of good X

•

Prelated goods = the prices of compliments or substitutes

•

Income (M) = the income of the buyers

•

Preferences = the preferences or tastes of the buyers

The demand function is a model

that “explains” the change in the

riceP

$8

dependent variable (quantity of the

$7

good X purchased by the buyer)

$6

$5

“caused” by a change in each of the

$4

independent variables. Since all the

$3

$2

independent variable may change at

Demand

$1

the same time it is useful to isolate

2

4

6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Quantity/ut

Figure III.A.1

the effects of a change in each of the

150

8.1.1 Individual Demand Function

independent variables. To represent the demand relationship graphically, the

effects of a change in PX on the QX are shown. The other variables, (Prelated goods,

M, preferences, . . . ) are held constant. Figure III.A.1 shows the graphical

representation of demand. Since (Prelated goods, M, preferences, . . . ) are held

constant, the demand function in the graph shows a relationship between PX

and QX in a given unit of time (ut).

The demand function can be viewed from two perspectives.

The demand is usually defined as a schedule of quantities that buyers are

willing and able to purchase at a schedule of prices in a given time

interval (ut), ceteris paribus.

QX = f(PX), given incomes, price of related goods, preferences, etc.

Demand can also be perceived as the maximum prices buyers are willing

and able to pay for each unit of output, ceteris paribus.

PX = f(QX), given incomes, price of related goods, preferences, etc.

It is important to remember that the demand function is usually thought of

as Q = f(P) but the graph is drawn with quantity on the X-axis and price on

the Y-axis. While demand is frequently stated Q = f(P), remember that

the graph and calculation of total revenue (TR) and marginal revenue (MR) are

calculated on the basis of a change in quantity (Q). TR = f(Q) The calculation

of “elasticity” is based on a change in quantity (Q) caused by a change in the

price (P). It is important to clarify which variable is independent and which is

dependent in a particular concept.

8.1.2 MARKET DEMAND FUNCTION

W hen property rights are nonattenuated (exclusive, enforceable and

transferable) the individual’s demand functions can be summed horizontally to

obtain the market demand function.

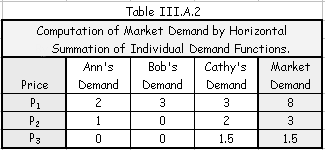

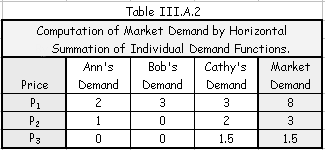

In Figure III.A.2 and Table III.A.2, a market demand function is

constructed from the behavior of three people (the participants in a very small

151

8.1.2 Market Demand Function

market. At a price of P1, Ann will voluntarily buy 2 units of the good based on

her preferences, income and the prices of related goods. Bob and Cathy buys

3 units each. Their demand functions are represented by DA, DB and DC in

Figure III.A.2.

rice

Figure III.A.2

P

DB

P3 D d

A

d

P2

Market Demand

DM

P1

DC

d

1

2

3

8

Q/ut

The total amount demanded by the three individuals at P1 is 8 units

(2+3+3). At a higher price each buys a smaller quantity. The demand

functions can be summed horizontally if the property rights to the good are

exclusive: Ann’s consumption of a unit precludes Bob or Cathy from the

consumption of that good. In the case of public (or collective) goods, the

consumption of national defense by one person (they are protected) does not

preclude others from the same good.

The behavior of a buyer was represented by the function:

QX = fX(PX, Prelated goods, income (M), preferences, . . . ). For the market

the demand function can be represented by adding the number of buyers (#B,

or population),

QX = fX(PX, Prelated goods, income (M), preferences, . . . #B)

152

8.1.2 Market Demand Function

Where #B represents the number of buyers. Using ceteris paribus the

market demand may be stated

QX = f(PX), given incomes, price of related goods, preferences, #B etc.

8.1.3 CHANGE IN QUANTITY DEMAND

W hen demand is stated Q = f(P) ceteris paribus, a change in the price of

the good causes a “change in quantity demanded.” The buyers respond to

a higher (lower) price by purchasing a smaller (larger) quantity. Demand is an

inverse relationship between price and quantity demanded. Only in unusual

circumstances (a highly inferior good, a Giffen good) may a demand function

have a positive relationship.

A change in quantity demanded is a movement along a demand function

caused by a change in price while other variables (incomes, prices of related

goods, preferences, number of buyers, etc) are held constant. A change in

quantity demanded is shown in Figure III.A.3.

An increase in quantity demanded is a movement

rice P

along a demand curve (from point A to B) caused

$8

by a decrease in the price from $7 to $4.

$7

A decrease in quantity demanded is a movement

A

$6

along the demand function (from point B to A)

caused by an increase in price from $4 to $7.

$5

$4

B

$3

$2

Demand

$1

2

4

6 8 10 12 14 16 18

Quantity/ut

Figure III.A.3

153

8.1.4 Change in Demand

8.1.4 CHANGE IN DEMAND

A change in demand is a “shift” or movement of the demand function. A

shift of the demand function can be caused by a change in:

• incomes

• the prices of related goods

• preferences

• the number of buyers.

• Etc . . .

A“change in demand” is shown in Figure III.A.4. Given the original demand

(Demand), 10 units will be purchased at a price of $5. An increase in demand

(DINCREASE) is to the right and at every price a larger quantity will be purchased.

At $5, eighteen units are purchased. A decrease in demand is a shift to the

left. At a price of $5 only 4 units are purchased. A smaller quantity will be

bought at each price.

Given a demand function (Demand), an increase in demand is

rice

shown as D

P

INCREASE. At each price a larger quantity is

purchased.

$8

Increase

A decrease in demand is shown as DDECREASE. At each

$7

Decrease

possible price the quantity purchased is less.

$6

H

$5

G

J

$4

$3

DINREASE

$2

Demand

$1

DDECREAS

E

2

4

6

8 10 12 14 16 18

Quantity/ut

Figure III.A.4

154

8.1.5 Inferior, Normal and Superior Goods

8.1.5 INFERIOR, NORMAL AND SUPERIOR GOODS

A change in income will usually shift the demand function. When a good

is a “normal” good, there is a positive relationship between the change in

income and change in demand: an increase in income will increase (shift the

demand to the right) demand. A decrease in income will decrease (shift the

demand to the left) demand.

An inferior good is characterized by an inverse or negative relationship

between the change in income and change in demand. An increase in the

income will decrease demand while a decrease in income will increase

demand.

rice P

$8

Increase

$7

Decrease

$6

H

$5

G

J

$4

$3

DINCREAS

$2

Demand E

$1

DDECREAS

E

2

4

6

8 10 12 14 16 18

Quantity/ut

Figure III.A.2

A superior good is a special case of the normal good. There is a positive

relationship between a change in income and the change in demand but, the

percentage change in the demand is greater than the percentage change in

income. In Figure III.A.2 an increase in income will shift the Demand function

(“Demand”) for a normal good to the right to DINCREASE. For an inferior good, a

decrease in income will shift the demand to the right. For a normal good a

decrease in income will shift the demand to DDECREASE.

155

8.1.6 Compliments and Substitutes

8.1.6 COMPLIMENTS AND SUBSTITUTES

T he demand for Xebecs (QX) is determined by the PX, income and the

prices of related goods (PR). Goods may be related as substitutes (consumers

perceive the goods as substitutes) or compliments (consumers use the goods

together). If goods are substitutes, (shown in Figure III.A.3) a change in PY (in

Panel B) will shift the demand for good X (in Panel A).

Substitutes

Price

Price

Goods X and Y are substitutes, An increase in

PY (from PY1 to PY2) decreases the quantity

PY2

demanded for Y from Y

D

1 to Y2. The demand for

Y

good X increases to DX*. At PX the amount

purchased increases from X

P

2 to X3. A decrease

X

D

in PY shifts DX to DX** (Amount of X

X*

P

decreases to X1).

Y1

D

D

X**

X

X1

X2

X3 Q

Y2

Y1

X /ut

QY /ut

Panel A

Panel B

Figure III.A.3

An increase in PY (from PY1 to PY2) will reduce the quantity demanded for

good Y (a move on DY). The reduced amount of Y will be replaced by

purchasing more X. This is a shift of the demand for good X to the right (In

Panel A, this is shown as a shift from DX to DX*, an increase in the demand for

good X). At PX a larger amount (X3) is purchased

A decrease in PY will increase the quantity demanded for good Y. This will

reduce the demand for good X, the demand for good X will shift to the left

(from DX to DX**, a decrease). At PX (and all prices of good X) a smaller

amount of X (X1) is purchased.

In the case of compliments, there is an inverse relationship between the

price of the compliment (PZ in Panel B, Figure III.A.4) and the demand for

156

8.1.6 Compliments and Substitutes

good X. An increase in the price of good Z will reduce the quantity demanded

for good Z. Since less Z is purchased, less X is needed to compliment the

reduced amount of Z (Z2). The demand for X in Panel A decreases for DX to

DX**. An decrease in PZ will increase the quantity demanded of good Z and

result in an increase in the demand for good X (from DX to DX* in Panel A).

Compliments

Price

Price

Goods X and Z are compliments, An increase in

PZ (from PZ1 to PZ2) decreases the quantity

PZ2

demanded for Z from Z

D

1 to Z2. The demand for

Z

good X decreases to DX**. At PX the amount

purchased decreases from X

P

2 to X1. A decrease

X

D

in PZ shifts DX to DX* (Amount of X increases

X*

P

to X3).

Z1

D

DX

X**

X1

X2

X3 Q

Z2

Z1

X /ut

QZ /ut

Panel A

Panel B

Figure III.A.4

8.1.7 EXPECTATIONS

E xpectations about the future prices of goods can cause the demand in

any period to shift. If buyers expect relative prices of a good will rise in future

periods, the demand may increase in the present period. An expectation that

the relative price of a good will fall in a future period may reduce the demand

in the current period.

8.2 SUPPLY FUNCTION

A supply function is a model that represents the behavior of the

producers and/or sellers in a market.

QXS = fS(PX, PINPUTS, technology, number of sellers, laws,

taxes, expectations . . . #S)

PX = price of the good,

157

8.2 Supply Function

PINPUTS = prices of the inputs (factors of production used)

Technology is the method of production (a production

function),

laws and regulations may impose more costly methods of

production

taxes and subsidies alter the costs of production

#S represents the number of sellers in the market.

Like the demand function, supply can be viewed from two perspectives:

Supply is a schedule of quantities that will be produced and offered for sale

at a schedule of prices in a given time period, ceteris paribus.

A supply function can be viewed as the minimum prices sellers are willing

to accept for given quantities of output, ceteris paribus.

8.2.1.1 (1) GRAPH OF SUPPLY

T he relationship between the quantity produced TABLE III.A.5

and offered for sale and the price reflects opportunity

SUPPLY

cost. Generally, it is assumed that there is a positive

FUNCTION

relationship between the price of the good and the PRICE QUANTITY

quantity offered for sale. Figure III.A.5 is a graphical

representation of a supply function. The equation for

$5

0

this supply function is Qsupplied= -10 + 2P. Table III.A5

$10

10

also represents this supply function.

$15

20

8.2.1.2 (2) CHANGE IN QUANTITY SUPPLIED

G

$20

30

iven the supply function, Qxs = fs(Px, Pinputs,

Tech, . . .), a change in the price of the good (PX) will

be reflected as a move along a supply function. In Figures III.A.5 and III.A.6

as the price increases from $10 to $15 the quantity supplied increases from 10

to 20. This can be visualized as a move from point A to point B on the supply

158

8.2 Supply Function

function. A “change in quantity supplied is a movement along a supply

function.” This can also be visualized as a movement from one row to

another in Table III.A.5.

Supply

8.2.1.3 (3) CHANGE IN SUPPLY

Price

C

iven the supply function, Q

$20

xs =

Gf

B

s(Px, Pinputs, Tech, . . ., #S), a

$15

change in the prices of inputs (Pinputs) or $10

A

technology will shift the supply function. A

$5

shift of the supply function to the right will

be called an increase in supply. This means

10

20

30 Q/ut

that at each possible price, a greater

Figure III.A.5

quantity will be offered for sale. In an

equation form, an increase in supply can be shown by an increase in the

quantity intercept. A decrease in supply is a shift to the left: at each possible

price a smaller quantity is offered for sale. In an equation this is shown as a

decrease in the intercept.

Supply

A change in quantity supplied is a movement along

Price

a supply function that is “caused” by a change in the

C

$20

price of the good. In the graph to the right, as price

increases from $10 to $15 the quantity supplied

B

$15

increases from 10 to 20. This can be visualized as a

move from point A to point B along the supply

A

function. A decrease in supply would be a move

$10

from point B to point A as price fell from $15 to $10

$5

10

20

30 Q/ut

Figure III.A.6

159

8.2 Supply Function

A change in supply is a “shift” of the supply

function. A decrease in supply is shown as a

Supply

shift from Supply to S

S

decrease in the graph. At

Price

decrease

C

a price of $15 a smaller amount is offered for

$20

sale. This decrease in supply might be

R

B

H

“caused” by an increase in input prices, taxes,

$15

E

Sincrease

regulations or, . . .

A

An increase in supply can be visualized as a

$10

movement of the supply function from

$5

Supply to Sincrease.

10

20

30 Q/ut

Figure III.A.7

8.3 EQUILIBRIUM

Webster’s Encylopedic Unabridged Dictionary of the English Language

defines equilibrium as “a state of rest or balance due to the equal action of

opposing forces,” and “ equal balance between any powers, influences, etc. ”

T

he New P

algrave : A Dictionary or Economics identifies 3 concepts of

equilibrium:

•

Equilibrium as a “balance of forces”

•

Equilibrium as “a point from which there is no endogenous ‘tendency to change’”

•

Equilibrium as an “ outcome which any given economic process might be said to be

‘tending towards’, as in the idea that competitive processes tend to produce

determinant outcomes.””

In Neoclassical microeconomics, “equilibrium” is perceived as the condition

where the quantity demanded is equal to the quantity supplied: the behavior

of all potential buyers is coordinated with the behavior of all potential sellers.

There is an equilibrium price that equates or balances the amount that agents

want to buy with the amount that is produced and offered for sale (at that

price). There are no forces (from buyers or sellers) that will alter the

160

8.3 Equilibrium

equilibrium price or equilibrium quantity. Graphically, economists represent a

market equilibrium as the intersection of the demand and supply functions.

This is shown in Figure III.A.8.

In the graph to the left, equilibrium is at the

Supply

intersection of the demand and supply

Price

C

functions. This occurs at point B. The

$20

equilibrium price is $15 and the equilibrium

quantity is 20 units.

B