Engineering students working on field projects in other countries face several communication challenges. Typically they come from a US college environment and are accustomed to live and learn among peers and professors in an English-speaking environment where codes of conduct are generally understood by all without paying too much specific attention to them.

When these students arrive in the developing country at their rural non-English speaking project site, things change on many levels. In addition to obvious language difficulties, basic assumptions about how to get things done and even whether things should be done will be challenged, sometimes openly, more often in many subtle ways.

Additionally, students working on outreach engineering projects all over the world face specific challenges not encountered by casual visitors or long time workers, such as Peace Corps volunteers or missionaries who are committed to several years in the foreign location. Student engineering groups are generally on location for 7 to 10 days during spring break or in the summer, and even though there may be repeated visits to the same village, the individual members of the group may change. These conditions create challenges that are specific to engineering communication in traditional societies.

This web site is designed to share with you some of the cultural challenges students have experienced in Engineers without Borders projects, help you identify common areas of difficulties, and suggest strategies to prepare to cope with them. The stories of these students’ varied projects, experiences, approaches, strategies, surprises, successes and failures were collected and discussed in a cross-cultural training course for engineering students at Rice University in Houston, Texas, USA in the spring semester 2007 under a grant from the Engineering Information Foundation. We hope that their accounts will help you anticipate the exciting and complex challenges of communication abroad.

Note

For students without experience in US culture.

The students who tested the modules for this project in class were United States engineering students of various cultural family backgrounds. Almost all of them had worked on engineering projects in El Salvador, Nicaragua or Mexico. One student had a special interest in and some experience in Mongolia and China. Examples and exercises in these modules assume familiarity with United States American culture, sometimes specifically in the United States college setting. If you use these materials and you are not familiar with the US American background, you would have to rethink the issues raised and substitute exercises and comparisons that would clarify the issues for you or your students.

Before you begin using this module and others in the course, you may wish to read portions of Iris Varner and Linda Beamer’s Intercultural Communication in the Global Workplace (2005), which focuses on the professional context of intercultural communication. Chapters 3 and 4 especially lay out the concepts of underlying values that affect behavior in different cultures. The context of traditionally structured societies, which the modules in this Connexions series address, differs from the professional context Varner and Beamer describe in the level of technical training that local partners for outreach projects have. Two excellent publications produced for the United States Peace Corps are also useful:

Learning Local Environmental Knowledge: A Volunteer’s Guide to Community Entry (Information Collection and Exchange Publication No. M0071, Peace Corps 2002) and

Culture Matters: The Peace Corps Cross-Cultural Workbook by Craig Storti, which is also available in English or in Spanish as

La Cultura Sí Importa: Manual Transcultural Del Cuerpo de Paz

as a free .pdf download at Peace Corps Web Site

Detecting Cultural Differences

When you want to work successfully in another culture, it becomes very important to understand the ‘language you yourself speak’, not just the words and the grammar of your own language, but the underlying, often subconscious, assumptions you make and the underlying values that you rely on. When you understand the implications of your own language, then it becomes easier to deal with the reality that the “language local people speak” is not just a literal translation of yours, but is embedded in their underlying cultural values and assumptions. Communication across cultures is not easy. As we all know, the possibility of misunderstanding is always present, even among members of the same culture who are communicating in the same language. The possibility of misunderstanding, even if everybody is of good will, is exponentially increased when you cross cultures.

EXERCISE

Ask each person in your group to take a standard sheet of 8 1/2” x 11” paper. Ask one person to read the following directions to the group. Without demonstrating or telling anyone how to hold or fold the paper, read the following words exactly, read slowly, and only read once. Or, if you are working independently, skip to 1.3, Comparing Cultures.

Ready to start? Stand up. Close your eyes and keep them closed throughout the exercise. Do not ask any questions.

Fold your piece of paper in half and tear off the bottom right corner.

Now, fold it in half again and tear off the upper right corner.

Now, fold it in half again and tear off the lower left corner.

Fold your piece of paper in half and tear off the bottom right corner.

Now, unfold the whole page. Compare your page with the other people’s. What do you notice?”

(Developed by Russel Dore, Fruehauf Corporation, Detroit, Michigan)

Result: The exercise demonstrates how easily misunderstandings develop, even among speakers of the same language, when not enough detail is provided, when clarification questions are not encouraged, and when non-verbal signs of hesitation or frustration are overlooked.

When you want to compare cultures and eventually identify specific differences that require special attention, cross-cultural trainers often use the picture of the iceberg. Only a small part, the tip of the iceberg, is visible, the major portion of the iceberg is submerged and can become dangerous to a ship. Everybody wants to avoid the calamity that befell the Titanic, the famous passenger ship that ran into an iceberg on her first voyage and sank, taking hundreds of passengers with her.

Applying this image, the tip of the iceberg shows the visible part of the culture or, more specifically, the part of the culture that can be perceived through all the senses, the things you can see, hear, feel, taste and smell: the architecture, the food, the music, the literature, the art and much more. This is the part of culture that the tourist is interested in and that the short-term visitor perceives as different, interesting and sometimes exotic.

Below the surface is the invisible part of culture, the differences that are perceived by long-term visitors, the people who try to live in the culture for an extended period of time. These people realize–often slowly–how essential the under-the-surface components of the culture are and how deeply they affect everyday life. Here we look at questions like: How do people identify themselves, as individuals or as members of the group? How is time perceived: is it controlled by the person or not? How are children raised–what are the most important things they have to learn? Are old people respected for their wisdom? What is important when people talk to each other–do they say things straight out, or do they assume that you know how to read between the lines? How is power distributed in the community? Who has it, and how much? In the submerged part of the iceberg of culture we find the values, the beliefs and the often subconscious assumptions that most members of the culture share.

In summary: Here is the important insight, especially for groups like engineering students, who want to work successfully with rural villagers on very short-term projects: the underlying values, beliefs and assumptions of a culture affect what you see on the surface in the behavior of the members of that culture. In other words, if you know something about the values, beliefs and assumptions of your own culture and the culture you are going to work with, if you understand the major differences, then it will become easier to deal with the behavior patterns of everyday interactions and you can become more creative and hopefully more successful in solving the big and little problems of getting your project completed.

When we talk about the US Americans we have to define on what we mean. Whenever you ask a culturally based question such as “How do you show friendliness and respect when you greet somebody?” to a large group of Americans in different parts of the country, in different population groups and at different age levels, you will get a wide variety of answers. Not all Americans act or think alike in the same situation. The many answers could be sorted statistically and the result would probably show a bell curve, a line through the apex would then show how most Americans would deal with the particular question. The same would hold for the foreign culture. The two bell curves might overlap indicating that some people in both cultures would deal with that question in the same way and would have fewer misunderstandings in dealing with each other. This example shows that all cultures have many variations. In general, these variations are more noticeable when you are in the country. When you look at a culture from the outside, the common elements tend to stand out.

US American Values and Beliefs

In your cross-cultural class you can brainstorm the most important US American values, beliefs and assumptions. You might come up with concepts like: individualism, self-reliance, competition, equality, can-do-spirit, hard work, informality, and a direct communication style.

There are many ways to study the main values of your own culture:

One way is to look at how children are raised in your culture. Parents all over the world want to teach their children what will make them successful in their culture. US American children are taught independence and self-reliance at an early age. “You can do that yourself,” “Figure it out,” “What do you think?” and “Ask your teacher, brother, grandpa” are phrases heard from parents and teachers.

Another way to study main values is to listen to comments of foreign visitors. Here are some quotes from foreigners who have worked or studied for a while in the US: The examples below werer taken from L. Robert Kohls and John M. Knight's Developing Intercultural Awareness: A Cross-cultural Training Handbook 1994:

“Americans seem to be in a perpetual hurry. Just watch the way they walk down the street. They never allow themselves the leisure to enjoy life; there are too many things to do.” (Visitor from India)

“In the US everything has to be talked about and analyzed. Even the littlest thing has to be “why? why? why?” I get a headache from such persistent questions. I still can’t stand a hard hitting argument.” (Visitor from Indonesia)

“The American seems very explicit, he wants a ‘Yes’ or “No’ – if someone tries to speak figuratively, the American is confused.” (Visitor from Ethiopia)

“I was surprised, in the United States, to find so many young people who were not living with their parents, although they were not yet married. Also, I was surprised to see so many single people of all ages living alone, eating alone, and walking the streets alone. The United States must be the loneliest country in the world.” (Visitor from Colombia)

“Imagine my astonishment when I went to the supermarket and looked at eggs. You know, there are no small eggs in America, they just don’t exist. They tend to be jumbo, extra large, large and medium. It does not matter that the medium are little. Small eggs don’t exist because, I guess, they think that might be bad or denigrating.” (Visitor from The Netherlands)

“What Bothers Nationals about Working with US Americans in Their Community” Adapted from: L. Robert Kohls, Survival Kit for Overseas Living 1984

We carry with us our own cultural baggage. When we work in a foreign environment, our way of doing things contrasts with the local way, and our attitudes and behaviors–which look positive to us–may appear differently in the foreign environment. Here are some characteristics of US American workers that have stood out in a foreign culture

They expect to accomplish more in the local environment than is reasonable.

They are insensitive to local customs and norms.

They resist working through normal administrative channels.

They often take credit for joint efforts.

They think they have all the right answers.

They are abrupt and task oriented, insensitive to the feelings of others.

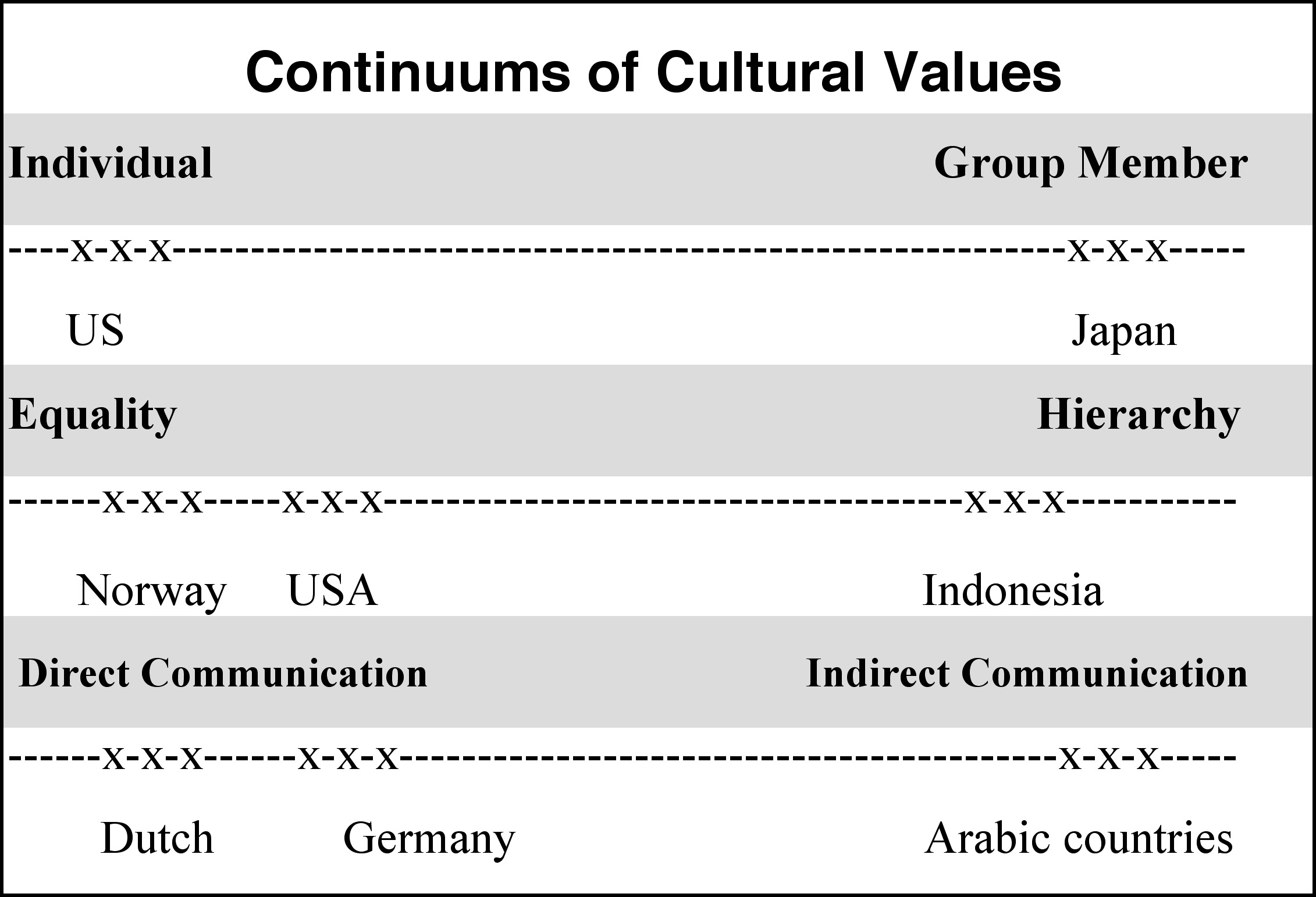

When you think about underlying values, beliefs and assumptions in different cultures, you can think in terms of continuums, with extremes on either end. Research has located cultures at various point on a value continuum. Some cultures can be found close to one end; other cultures may be found closer to the opposite end. For example,members of some cultures think about themselves as independently acting individuals; members of other cultures think primarily of themselves as integral members of a group, with primary responsibilities toward that group.

Other cultures could be located on these continuum lines and similar lines could be drawn for other values, beliefs and assumptions. The locations are not engraved in stone but are simply guidelines to stimulate observation, questions and discussion in preparing to work in another culture.

People have different styles of communication. Some people are direct: they rely on words and data. Other people are indirect: they suggest, they hint at what they really mean, they don’t just use a precise word, they may use a descriptive phrase or a picture, or tell a story and expect the listener to infer the meaning. In the same way, languages and the cultures they express can be either more direct or more indirect, more precise or more vague. The Dutch speaker will know that the Dutch listener will expect directness, even bluntness, and will not be offended. The Japanese speaker, on the other side, will know that he does not have to be precise; the listener will take into consideration the surroundings, the subtle non-verbal message, and will understand; and by avoiding directness, face will be saved for both sides.

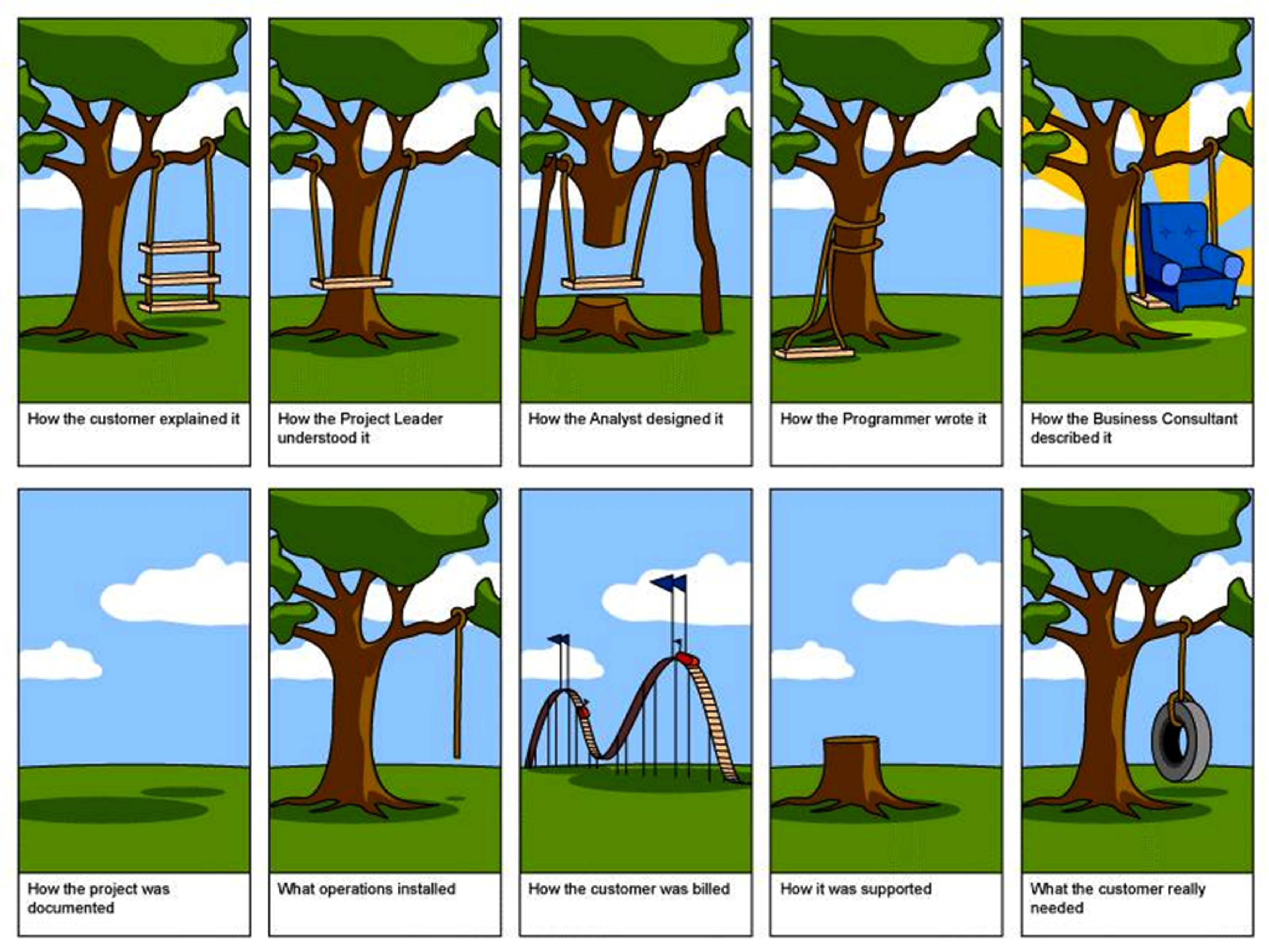

To illustrate the possible frustration and resulting non-communication, let me tell you about one of my experiences. I remember that in China I once listened with a group of other US Americans to a lecture by a Chinese professor on Chinese watercolor painting. The professor spoke excellent grammatically correct English, but the Chinese indirect communication style came through so strongly that most Americans could not follow the circles and spirals of the thought patterns and simply grew too tired to listen. They were accustomed to a much more direct style that quickly got to the point and stated each point clearly and as a result, they missed learning more about a very special form of art.