the right threshold for their organization, even though it could turn to not be sufficient

too, in that a financial threshold should be, in theory, identified for each person (Longo,

2012).

Yet, it should not be overlooked that on doing so, employers should also keep into

consideration the circumstance that the reward packages they offer to their employees

also have to be perceived as equitable and fair by all of them. Whereas on the one hand

individuals tend to consider as fair and adequate the reward packages whose financial

component will enable them to live relatively comfortable lives, employers should make

18

Reward Management

sure, on the other hand, that the reward packages they offer are considered and

perceived as fair and consistent by the entire workforce. In other words, trying to

identify individuals’ needs and expectations does not mean creating unjustified inequality

and unfairness (Longo, 2012).

It clearly emerges that designing and developing reward management systems, and

express them by means of adequate and consistent practices and policies, is everything

but straightforward. Nevertheless, employers should be aware of the importance of

meeting, as far as possible, individuals’ wants and expectations, as well as is important

that they are aware of all of the likely pitfalls associated with designing and introducing

inconsistent and unfair reward practices and systems. The task is genuinely challenging

and that is why employers need to build synergism with other forms of rewards, namely

flexible and voluntary benefits, in order to attain the desired objective.

The impact of the changing content of the psychological contract

over reward management practices

Individuals’ preferences, needs and expectations are not actually influenced only by

personal occurrences. Even though, in general, a more direct link between personal

difficulties and individuals need for salary increases can in fact be identified; in practice

individuals’ wants and expectations are not just influenced by adversities.

Still focusing on the financial component of reward only, it can be said that individuals’

keen interest for the one or the other element of the reward packages they receive from

their employers is indeed influenced by a whole range of different factors. Yet,

individuals’ needs and expectations cannot only be met by the financial component of

the reward packages they receive. Finally, individuals’ preferences are not static, but can

be considered somewhat of dynamic, meaning by that that these are subject to change

over time.

Acquiring an overarching, in-depth knowledge of individuals wants and being able to

promptly capture changes in people’s needs and expectations, not to mention the ability

to understand future trends, can clearly reveal to be crucially important to design,

develop and introduce effectual reward management practices within an organization.

In broad terms, it can be said that, essentially, employers aim and strive to have, as far

as possible, recourse to sophisticated, craftily devised reward management practices

because they are expected them to pay off. To put it another way, employers try to

meet their own expectations by meeting those of their employees and that is why it is

said that reward management practices need to satisfy both employers’ and employees’

needs.

As it is widely recognised, one of the topics at the top of business leaders’ agenda is staff

motivation which, together with employee commitment and engagement, definitely

represents one of the current top priorities for every employer. Reward managers and

specialist should hence consider enabling employers to achieve this objective or, the

19

Reward Management

worse comes to the worst, helping them as effectively as possible to attain it, their first

priority.

Finding effective and sound ways to motivate and engage staff is clearly seen and

perceived by employers as a no mean feat. Especially in periods dominated by harsh

competition or during phases of financial downturn and slowdown, when employers have

to tighten their belts in order to maintain their competitiveness, the human capital factor,

that is, the only factor which can hardly or even impossibly be replicated, is broadly

recognised as the only and most powerful factor which can actually contribute

organizations competitive edge (Longo, 2011a).

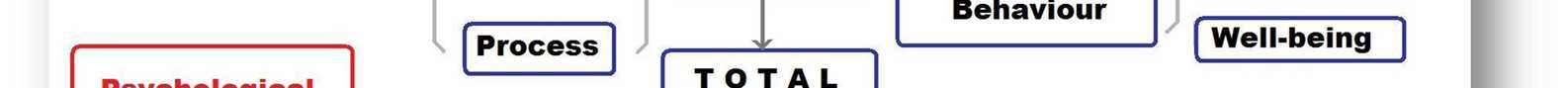

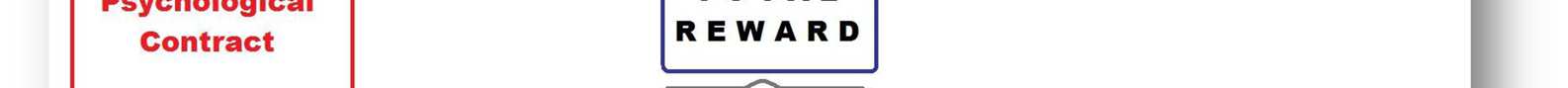

But how can in practice employers encourage discretionary behaviour and induce their

staff to go the extra mile in order to achieve the desired level of performance? The

answer should be found in the root of every employment relationship, namely the

psychological contract according to which individuals commit themselves to perform

working activities for their employers in exchange for a not exactly specified and

generically defined “reward.” This conundrum is actually not as straightforward as it

might seem to deal with. As we have seen the meaning and content of reward is unlikely

to be the same for the different individuals concerned within an organization, as well as

it is unlikely that this meaning and content would remain stable and invariable over time

for the same individuals concerned (Longo, 2011a).

People identify different goals to satisfy their different needs and act differently to attain

their identified goals (Armstrong, 2006), the one-size-fits-all approach to motivation is,

hence, very unlikely to produce appreciable results. The most effective, and, to some

extent, most obvious approach to deal with the issue would just be to give each

individual what he/she actually wants and would like to receive (Longo, 2011a).

Individual’s preferences can, in general, be investigated by means of focus groups, “have

your say” communication sessions, staff consultation forums, large group sessions,

internal surveys and other similar initiatives. Since it is not only people who are subject

to change, but also the world around them, a thorough and comprehensive investigation

cannot miss to consider the external environment too (Longo, 2011a).

As described in paragraph 4, a PESTLE investigation can definitely help employers to

anticipate future trends and their influence on individuals’ preferences. An evidence of

the impact and relevance of the role played, for instance, by the legal framework within

which organizations operate is provided by the findings of the study “Benefits around the

world Report 2011” carried out by Mercer (Mercer, 2011). The findings of this

investigation basically revealed that multinational organizations have been prompted to

introduce remarkable changes in response to states pension and health and welfare

reforms. Indeed, structural pensions and health provisions reforms have been introduced

in many countries across the world essentially generating a gap between what

employees were expected to receive after their retirement and what they will actually

receive. This aspect, especially in the light of the ageing population phenomenon and of

the consequent international trend according to which retirement age tends to be risen,

20

Reward Management

has led organizations to design and implement different approaches in order to bridge

this gap (Longo, 2011a). This is an example of an aspect that, whether could have been

previously perceived as less important by individuals, is now considered as one of the

most important employers have to care about in order to honour the psychological

contract.

Most importantly, the findings of the studies and investigations carried out over the

years have revealed that individuals are not motivated just by the extrinsic and financial

component of reward; research has suggested that people are much more motivated by

intrinsic, non-financial rewards and find much more motivation in their jobs rather than

in the pay they receive to carry them out.

Clearly, over the years the content of the psychological contract has changed, providing

evidence on the one hand that what individuals want and are expected to receive from

their employer is not stable and on the other hand that employers are the weakest of the

two parties involved in the contract. The change and evolution of the psychological

contract content in fact very much depends on employees rather than on employers ever

changing expectations.

In order to duly consider individuals’ continuously changing needs and to balance the

effects of financial and non-financial reward (whatever the emphasis on non-financial

component of reward, employees would not work if they would not receive a salary),

relatively recently, a new concept of reward has been developed, that is, that of total

reward.

In broad terms, according to the total reward approach reward packages have to be

developed and built up on two distinct main components: a financial/extrinsic component

and a non-financial/intrinsic one. The design and development of this kind of models is

based on the idea, supported by decades of studies and investigations, that financial

reward is not a so effective and powerful motivator as it might seem, at least in the mid

and long run. Findings of dozens of investigations and surveys carried out over the years

have revealed that financial rewards can help organizations to attract individuals during

the recruitment process, but that these cannot be considered as a powerful and effective

motivator during the employment relationship. Emphasis has, instead, to be given to the

development, involvement and participation of individuals. Taking care with both of

these aspects, total reward approaches can effectively help employers to promptly

respond to their employees changing needs and meet individuals’ expectations based on

the content of their unwritten psychological contract (Longo, 2011a).

The external environment is constantly exposed to changes and clearly individuals’

needs are determined and influenced by what happens in the exogenous environment.

Inasmuch as the external environment is changing the faster and faster, individuals’

needs are subject to change at the same speed. In order to retain their staff employers

need to be aware of this circumstance and need to be able to having recourse to the

appropriate tools in order to investigate the phenomenon (Longo, 2011a).

21

Reward Management

Reward, or rather, total reward is clearly of pivotal importance and has a relevant role in

the process; employers resorting to well designed and flexible total reward approaches

should be able to face the changing conditions promptly and effectively and to adapt,

hence, their offering to the changing content of the psychological contract without any

particular difficulty (Longo, 2011a).

There is, nonetheless, a circumstance which employers should really neither overlook

nor underestimate: inasmuch as individuals are different one another, not necessarily all

of them, although certainly the greatest number of them, long for professional growth.

This is actually not the case of those who would like to quickly climb the career ladder

but do not do anything in practice to attain this objective, but rather the case of those

who are not interested to approach the ladder itself.

The Job Characteristics Model developed by Hackman and Oldham (1974), which is a

contingent rather than a universal approach like the Hierarchy of needs developed in

1943 by Maslow (1954), shows that not all of the individuals have the same level of

Growth Need Strength (GNS). In particular, people with low GNS are not interested in:

-

Intrinsic reward, they do not look for the variety of the job performed, skill

variety;

-

Task identity either, that is, with the importance of their role in the overall

organizational process;

-

Knowing the impact of their job on other employees’ jobs, task significance.

Yet, people with low GNS do not feel rewarded by higher level of autonomy and are

not that much interested in receiving feedback from their managers about their

performance. Such individuals do not therefore receive any benefit from intrinsic reward,

on the contrary, if forced beyond their desired level of GNS, results could be

counterproductive and they could even perform below their usual standard. As the

matter of fact, there are not so many individuals having low GNS, but these kinds of

cases have to be promptly identified by employers and treated accordingly. More often

than not, this is case of individuals (mostly, but not necessarily, involved in mechanical

jobs) who feel more comfortable being rewarded by extra cash only for their good

performance (Longo, 2011a).

It can be concluded that the main element contributing to make reward practices

particularly tricky to manage is represented by people variety and diversity and by the

dynamic mechanism according to which individuals’ wants and preferences change with

the passing of time.

Employers have to be aware that not meeting individual needs, nonetheless, has not to

be simply considered as generating disappointment in the people concerned; such

occurrence in actual fact causes in people the even worse feeling that their psychological

contract has been breached by the employer. Should this undesirable circumstance

happen, it is very likely to generate negative behaviour and unsatisfactory performance.

Employers need by extension to pay extra care to this particularly sensitive aspect.

22

Reward Management

Reward management in a framework context

Despite many argue that attributing to financial reward a motivating effect should be

considered questionable, it can be taken as axiomatic that whether employers are paying

a growing attention to this aspect it is only because they believe that, in one way or

another, financial rewards have a role to play and, although to different degrees, can

actually influence individual behaviour. To put it in a different way, albeit employers

might be persuaded that money does not motivate people, they are aware that, even

though not homogenously, individuals attach to it an indeterminate degree of

importance that they cannot really afford to overlook.

Financial reward might not be hence considered as a means to an end, but it surely

needs to be considered as part of the means. Yet, Herzberg’s definition of money as a

hygiene factor, after all, recognizes and attaches to financial reward a meaning and a

certain degree of importance, even though to a negative extent, that is, as demotivating

individuals if not perceived as fair and quantitatively adequate.

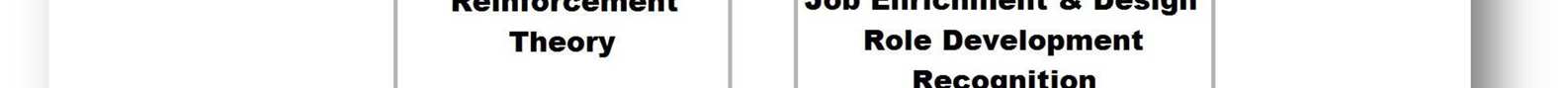

It can ultimately be maintained that analysing the role played by financial reward over

people’s motivation per se could be considered inappropriate and partial. Held in

isolation and as the only factor used to influence people’s behaviour and actions, it is

very unlikely in fact that financial reward could reveal to be an effective means to the

motivation end; whereas used as part of a wider and more extensive plan of action

aiming to induce employee discretionary behaviour, financial reward will surely reveal to

be an employers’ more effective allied. After all, it is very unlikely that employers could

ever be able to attain this ambitious objective having recourse to a single element,

initiative or action.

Table 3 - Elements of a synergic motivational plan of action

23

Reward Management

To this degree, by extension, financial reward needs to be better considered as part of a

framework where, used in synergy with other non-financial reward components, it can

more successfully be used. It is, essentially, an example of practical application of the

bundle approach based on the tenet “more is better.”

Resorting to a specific model will also reveal to be particularly useful in order to

introduce some concepts and ideas which are particularly important and necessarily need

to be known and understood by employers and reward specialists as well to design and

develop more appropriate, effective and consistent reward strategies and practices.

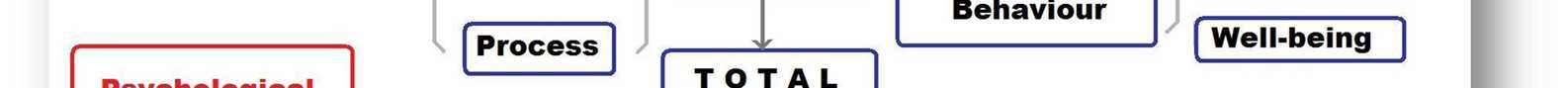

The framework described in Table 4 tries to provide employers with an example of how

reward management can effectively be used in combination, that is, in synergy with

other elements in order to influence individuals’ behaviour and performance.

Table 4 - The Motivation Framework

The first step of the process consists in identifying individual’s needs, aim which can

effectively be attained resorting to content theories. It becomes important, hence,

determine how individuals choose, amongst the available options, a specific plan of

action to satisfy their needs; the reference being, instead, here to process theories.

After having carried out these two first investigations, employers can analyse the

information gathered and use them accordingly. The ultimate scope is to influence

employees’ actions developing and introducing appropriate and consistent HRM practices.

It should not be overlooked in fact that HRM policies aligned with the overall business

strategy basically aim at inducing those behaviour and actions considered crucial for the

24

Reward Management

successful attainment of organizational strategy and, consequently, business success.

The final stage of the framework focuses on determining the most suitable behavioural

management style, consistently with organizations’ values and shared beliefs, in order to

win workforce’s trust and inspire integrity (Longo, 2011b).

The importance of the psychological contract

People in charge of carrying out the process should be well aware that throughout the

process particular attention has to be paid to the psychological contract. Both employers

and employees in fact from the very beginning, namely the moment the working

relationship has been established, have reciprocal expectations and these expectations

actually represent the basis of the psychological contract (Longo, 2011b).

The solidity and strength of this unwritten contract very much depend on individuals’

trust in their employers and, more in particular, on individuals’ belief and confidence that

their employers will “honour this deal” (Guest and Conway, 2002). This really is a

sensitive issue in that, although we are looking at an unwritten contract, the eventual

breach of this “reciprocal obligation” from the employer’s side is very likely to trigger

remarkably negative effects in that it would be perceived by employees as a threat to

their job stability (Porter and al., 2006). Individuals’ commitment and engagement

would decline and with them performance and staff’s willingness to go the extra mile. It

is the overall organization’s capability of gaining competitive edge which would be

exposed to danger (Longo, 2011b).

Content theories

Broadly speaking, in the past, two theories have been dominating the subject of the

reward-motivation supposed link: one was based on the existence of a strong and direct

cause-effect relationship between these two elements (Taylor, 1917), whereas the other

was underpinned by the concept that people are motivated by the social factor rather

than by the financial one (Follett, 1926 and Mayo, 1949).

In order to properly investigate the phenomenon, it is, first of all, important to duly

consider whether individuals’ needs can be clearly collectively identified.

Alderfer (1972) suggests that in every person there are the same wants. Individuals’

needs are, however, differently perceived and this diversity very much depends on the

different importance and level of priority that every individual attaches to each different

need. This aspect, which could apparently be considered of secondary importance or just

as a nuance, is instead of paramount importance. The significance that every person

associates with each need in fact modifies the perception of each individual towards the

same need, making ultimately individuals’ wants different according to every person’s

different perception (Longo, 2011b).

Particularly relevant amongst the content theories is also the two-factor theory

developed by Frederick Herzberg (1957). More in particular, Herzberg carried out a

thorough investigation about the factors affecting people motivation r