occasion of specifically organized public events, is also correlated to other two mental

processes called by Jeffrey (2003) evaluability and justifiability. The concept of

evaluability is linked to the value which different individuals can associate with a non-

financial or para-financial award which, in some circumstances, might also be perceived

as higher than the real purchasing cost of the item or service provided by the

organization. The idea of justifiability is instead associated with the circumstance that,

even though individuals could have bought by themselves the articles they receive from

their employer as a “thank you”, they do not in that might consider those items or

services particularly costly and in some ways not necessary for themselves and their

families (or anyway not worth the sacrifice necessary to buy these). This, however, does

not really entails by any means that they do not appreciate and justify, receiving them

from their employers.

Para-financial rewards will be even more welcomed and appreciated by individuals

whether these have been chosen by an employer having in mind the beneficiary

expectations and wants. This will unquestionably proof that the employer has dedicated

time and thoughts to the individual and that its efforts were focused on providing the

employee something he/she would have genuinely appreciated. This case is remarkably

different from the case in which as employer would award the employee with something,

maybe even cheap and outmoded, just for the sake of giving something (Rose, 2011).

Reward managers and specialists have to be extremely careful when designing and,

above all, managing these schemes and need to do whatever they can in order to avert

the disadvantages usually associated with the implementation of these programmes,

which can trigger dissatisfaction and discontent amongst the individuals not receiving

any form of award (Armstrong, 2010).

As maintained by Rose (2011) it is somewhat ludicrous that employers spend much

more than half of their overall annual budgets in reward and employees neither

appreciate their worthiness nor “understand what it is about.” The real true is that in

many cases employers too have not totally clear how and why they offer rewards to their

employees. This is certainly causing confusion amongst individuals but also amongst

business leaders and managers. If rewards are intended as the sum of pay and

incentives and recognition schemes as a means to say “thank you” to individuals,

managers need to be aware that in order to award a specific achievement is not a salary

178

Reward and Recognition

increase that they have to ask for to the employer. Similarly, whether they want to

acknowledge the regular and sustained outstanding performance of a direct report it is

not a flat-screen colour TV that they have to propose for the individual concerned. The

mechanism of these rules have to be clearly identified from the outset and hence shared

within the entire organization’s management in order to avert triggering potentially

dangerous drawbacks, unintended negative outcomes and indirectly foster undesirable

behaviour.

The BA model distinguishing fixed salary from incentives and recognition schemes, can

reveal to be clearer to understand and hence to explain and execute. Indeed, this

scheme enable both managers and employees to associate specific reasons with each

element of reward: fixed salary – paid according to the salary grade system, incentives –

to award outstanding, sustained performance and results, and recognition – to thanks

employees for specific achievements and behaviour.

Recognition does not actually represent an additional form of reward, but rather a

further and effectual way to implement reward practices and, to some degree, an

additional tool enabling reward managers and specialists to put the organization reward

system in order, assigning to each form of reward a specific and clear purpose and

objective. Like all of the other tools, however, its effectiveness is essentially relying on

its use; managers need to know the mechanism of the system and being able to

consistently execute it in practice.

179

References

American Productivity and Quality Center, (2002), Rewards and Recognition in

Knowledge Management; Houston: APQC.

Armstrong, M. , (2010), Armstrong’s handbook of reward management – Improving

performance through reward, 3rd Edition; London: Kogan Page.

Limaye, A. and Sharma, R. , (2012), Rewards and recognition: Make a difference to the

talent in your organization; Mumbai: Great Place to Work Institute India.

Jeffrey, S. , (2003), The benefits of tangible non-monetary incentives – Executive white

paper, The SITE Foundation.

Juran, J. , (2003), Juran on leadership for quality; New York: Simon and Schuster.

Longo, R. , (2010), Reward Management and Philosophy – What you need to define

before formulating your policy, HR Professionals.

Oxford Corpus, (2005), Oxford Dictionary of English, 2nd Edition; Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Rose, M. , (2011), Using non-cash reward: recognition, incentives and reward,

Developing Reward Strategies, January 2011, Pages 19-22.

Silverman, M. , (2004), Non-financial recognition. The most effective of rewards? ;

Brighton: Institute for Employment Studies.

Stewart, N. , (2011), Making it meaningful: Recognizing and Rewarding Employees in

Canadian Organization – Report April 2011; Ottawa: the Conference Board of Canada.

Torrington, D., Hall, L. and Taylor, S. , (2008), Human Resource Management, 7th

Edition; London: Prentice Hall.

Workspan, (2006), Leveraging recognition: non-cash incentives to improve

performance, November 2006.

180

Section IX

Getting ready for designing

and developing a reward

system

The importance of an equitable and fair approach to reward

management

Sage old Chinese people use to say that all men’s troubles derive from their mouths:

namely from what they say and what they eat. Financial reward risks playing the same

role for companies. Unfair, inequitable and unjust financial rewards systems in fact risk

seriously jeopardizing organizational success, social relationships and the correct and

regular unfolding of the daily working activities within an organization.

Whatever the reward philosophies and strategies pursued by a company, employers

should never neglect nor underestimate the importance of money. Organizations should

pay extra care to cash, as a crucial component of the reward packages they offer, not

only for its hygiene attribute, but also for the equitable and fair image and

representation of the overall reward and management system it can and should

contribute to foster and promote within the business (Longo, 2012).

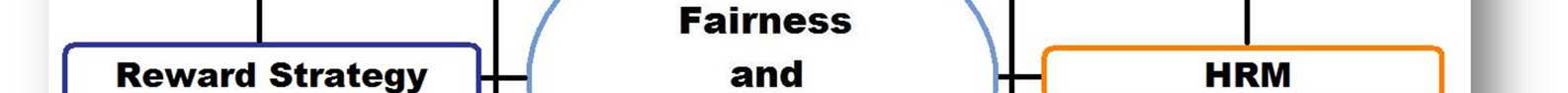

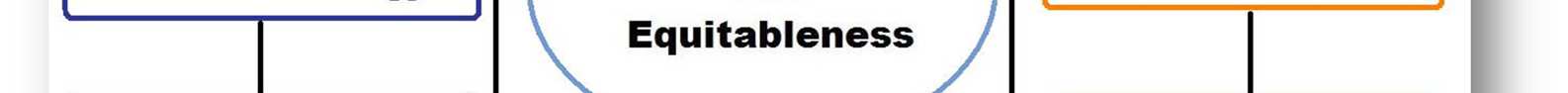

Inasmuch as fairness and equitableness are crucially important general values, which

should characterize each aspect and process within every workplace, these features

become even more important when associated with reward management. As contended

by Armstrong (2009), fairness, equitableness and consistency should be put at the basis,

as the founding pillars, of every reward management approach. Reward strategies, the

philosophies underpinning these and the practices by means of which strategies are

executed, together with HR strategy and practices, should therefore also strongly

contribute to promote fairness and equitableness within every organization. This process

will in turn help employers to reinforce organizational values and shared beliefs and to

foster integrity and the desired behaviour in the workplace (Longo, 2012).

181

Getting ready for designing and developing a Reward System

According to the ACAS (2005), salary has a remarkable impact on working relationships;

employers should consequently develop pay schemes capable of fairly rewarding

individuals according to the results they actually produce. Reward can and should be

used by employers as the most effective, practical means to provide their employees

tangible evidence of integrity and consistency within the workplace. As maintained by

Armstrong (2009), reward practices should thus be used by employers to treat

individuals fairly and not as something which could even reveal to be harmful for

organizations.

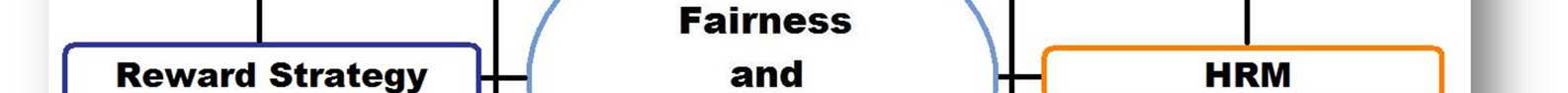

Table 27 – Reward contribution to organizational fairness

182

Getting ready for designing and developing a Reward System

Bankers’ bonus schemes misuse is a good, or rather, a bad example of how reward

practices can turn to be detrimental for an organization. Unfortunately, the banking and

financial industry is not the only example of bad reward practices design and

implementation. Just a very few years ago general public in the UK was appalled at

learning that civil executives were receiving a staggering £47 million in bonuses,

whereas there were soldiers receiving annual salaries worth less than £17,000. The

circumstance that, in the UK, some hospitality organizations included tips in staff’s

salaries in order to meet the national minimum wage requirements set by the existing

provisions definitely represented another dreadful example of very bad and unfair

reward practices (Keefe, 2010). Although it must be observed that, with reference to this

particular deplorable case like in others, the UK legal system promptly took action and as

a consequence of that from October 2009 bars and restaurants owners are no longer

permitted to consider gratuities as part of employee salaries (Keefe, 2010).

In general, employers can decide to have recourse to a variety of different approaches in

order to set pay levels and individuals’ reward packages composition, but, irrespective of

the approach they might choose to implement, what matters the most is that the

method they have selected could actually enable them to let employees perceive and

consider the existing reward system as both fair and equitable (Torrington et al, 2008).

Although this phenomenon has captured a wider interest and attention in the mid to late

2000s by reason of the bankers’ bonuses scandal and of the likely domino effect these

produced, in that deemed by many to have triggered the international financial crisis,

this is not really an occurrence typical of recent times only. As discussed in section one,

the negative impact on individual motivation and satisfaction caused by a reward system

perceived as inequitable and unfair by individuals had in fact already been thoroughly

investigated by John Stacey Adams back in the mid-1960s.

Whenever individuals feel that their output, which they deem equal or even superior to

that produced by their colleagues, is not rewarded accordingly, they feel and consider

breached their psychological contract. In other words, in such circumstances employees

believe that the employer treat them neither fairly nor equitably. Individuals show, by

extension, signs of dissatisfaction which will be practically manifested in a series of

actions such as increased absenteeism, desire to leave the organization, poor

performance and lack of trust on the company employee relations practices (Torrington

et al, 2008). As suggested by Robertson (Keefe, 2010), the problem is not that much

associated with the level of reward in general, which could also be lower vis-à-vis that

available for the same roles in the external environment, but rather with the internal

inequalities, which can also “destabilise” a business. Such bad practices are actually

likely to directly and indirectly have remarkable effects upon an organization budget. On

the one hand sickness and higher employee turnover rate would clearly account for

additional considerable costs; on the other hand repercussions of employee resentment

will also be reflected in poor customer service, which could in turn provoke a negative

impact on customers’ appreciation of the firm and of its products and services (Cotton,

2010).

183

Getting ready for designing and developing a Reward System

Fair and equitable, however, is not the same as and has not to be confused with equal.

People do not tend to criticise and judge as inappropriate disparity in reward per se.

Even considerable differences in treatment, both at pay and benefits levels, could be

accepted by individuals when these are perceived and deemed as justified by objectives

circumstances (Kessler, 2010). Individuals would certainly accept high bonuses for

executives and senior management positions, provided that these are reasonable,

justified and, most of all, “proportionate to the need” (Keefe, 2010). More in details,

Reilly (Keefe, 2010) explains that these differences are accepted when these are directly

linked to reasonable factors, namely “working hard, helping others, contributing more

and working longer hours.”

This clearly is also a matter of culture, the approach to reward management should

definitely be consistent and coherent with the culture an organization is aiming to foster

and promote. Before going towards a direction, whatever it might be, employers should

be sure that their decisions will be clearly understood and accepted by everybody,

differently this could produce a series of drawbacks, negative effects and ultimately

divisiveness within the business.

Line Managers should clearly be bright and prepared to identify and assess these cases

as soon as they arise. When a big negative change in individuals behaviour should be

identified, as for instance could be the case of an unusually increasing trend of the

“throw a sickie” phenomenon, line managers should try to analyse and determine

whether recent events associated with salary or grade increases granted to other

members of staff could be at the basis of that behaviour. What matters is not what the

employer, even conscientiously, has decided to do, but how that decision is perceived

and felt by individuals.

Employee participation and contribution to the pay determination process can

unquestionably contribute to make the implementation procedure easier, as well as can

communication and the explanation to the entire workforce of the mechanism and

reasons which have accounted for the identification of that particular method.

Notwithstanding, communication is clearly pointless whether it is not strictly coupled

with transparency and clarity. Employers and reward specialists should also make some

efforts in order to ensure that the pay determination approach and the way it will be

executed is clearly understood and learned by all of the individuals concerned

(Torrington et al, 2008).

A similar approach should also be used by businesses when planning to introduce

changes in the current pay schemes. As stressed by the ACAS (2005), in order to avoid

legal actions to be taken by staff, employers should agree with employees and their

representatives the planned changes on pay schemes before these are implemented.

This approach will clearly help organizations to ensure that the new system is accepted

and perceived as fair by staff.

184

Getting ready for designing and developing a Reward System

There is actually another area which might represent, especially in the years to come, a

cause for employers concerns. As pointed out by Keefe (2010), employers could soon be

confronted with staff complaints of unfair and unequal treatment as for what concerns

the changes in the pension schemes they have introduced and implemented within their

organizations. During the very last few years many employers have, and many

processes are indeed still underway, changed their pension schemes switching from the

defined benefit (DB) to the defined contribution (DC) scheme. Although all or part of

these schemes’ changes have possibly been agreed with trade unions and employees

representatives, it cannot either be neglected nor excluded that, as warned by Biggs

(2010), these differences could give raise to tensions within organizations during the

next years.

When developing pay systems, it might reveal to be particularly difficult for employers

make sure that these are perceived as fair by everybody, notwithstanding employers

who introduce equitable procedures will be the most likely to attain the most appreciable

and effective results (Torrington et al, 2008).

Businesses should also care about the felt-fair aspect of the reward packages they offer.

The circumstance that “ensuring that reward is internally fair” is an issue which has

regularly emerged in the CIPD Reward Management Surveys (CIPD, 2010 - 2011) is

clearly self-explanatory.

What must be known before starting

Inasmuch as devising fair and equitable reward systems is crucially important for

employers to attain their intended strategies and objectives, there are a number of

factors and concepts, theories included, which have to be necessary known by reward

professionals and practitioners in order to design and develop effective and consistent

reward schemes appropriately fitting both individuals and employers wants and

expectations.

Relevant theories

Efficiency wage theory

Also known as “economy of high wages theory”, this theory is based on the tenet that

paying higher-than-market rate salaries will enable organizations to attract, retain and

motivate staff. This theory is also aimed at curbing labour turnover and persuading staff

that they are treated fairly.

Employers have usually recourse to this approach when they want to be considered

market leaders and branding themselves as above-the-average employers.

Human capital theory

This theory aims at building on the staff education and skills to generate productive

capital and leading to a win-win situation for both employers and employees. Individuals

investing in order to enhance their personal skills and capabilities can be expected to

185

Getting ready for designing and developing a Reward System

receive better levels of pay and capitalize on these increased qualities to ensure job

security, whereas employers can expect from employees a better return on investment

in terms of both performance, productivity and, most of all, innovation.

Agency theory

According to this theory the owners/principals of an organization are considered

separated from the employees/agents, this is likely to generate “agency costs” in that

agents are not genuinely interested in the business as owners are. Consequently

principals are expected that agents will not be as productive as they would be and need

hence to find persuasive ways to motivate and engage these.

Employers, who decide to develop their businesses reward practices having recourse to

the agency theory, require to set out effective incentive schemes based on paying

individuals according to measureable results. This is considered the only option available

for employers to induce managers to effectively and genuinely do whatever they can in

order to pursue the employers’ interest.

<