Individuals have a complete control of the results yielded by their work and a

precise line of sight between performance and reward can clearly be identified;

Neither teamwork nor cooperation with other colleagues have significant effects

or impact on the results produced by the single individuals;

The existence of these conditions are justified and supported by a rather

individualistic organizational culture (Gomez-Mejia and Balkin, 1992).

In a company fostering a culture based on teamwork and collectivist principles at large,

such an approach would be clearly immediately perceived by employees as inconsistent,

it would undermine the firm integrity and would be ultimately contrasted and resisted by

staff.

According to the CIPD (2012), performance-related pay approaches are more likely to be

effective in private sector organizations and even more in financial services organizations

where having recourse to reward systems based on the performance-related pay

mechanism represents basically the norm. Habitually, these arrangements are most

likely to be used at managerial and administrative levels rather than at manual or shop

floor staff levels.

291

Variable reward schemes

Research has revealed that these programmes are more likely to be effective and

successful in those organizations where goals are clearly shared and understood by staff,

compensation is considered adequate and organizational culture supports merit-pay

schemes (Greiner et al, 1977). According to de Silva (1998), also the existence within

the organization of a performance management process, nonetheless, represents a

mandatory prerequisite. The performance management process should, more specifically,

ensure that some crucial activities have been prepared and carried out (IDS, 1997),

amongst these, organizational planning meant as the definition of the objectives and the

main skills required to effectively achieve them. Objectives will clearly be set according

to the overall organizational strategy and aims and should appropriately be

communicated within the business. The identification of performance measurement and

of the ratings on the basis of which salary increases and bonuses are offered is clearly of

paramount importance too. In order to this type of schemes be successful, performance

management should also take into due consideration and wisely balance the individuals’

aspirations and wants with those of the employer.

Once again, line managers’ importance and full involvement in the process is crucial.

These should be hence appropriately and thoroughly trained and ready to take

responsibility to manage the performance management process.

The existence of a performance management process based on these pillars, coupled

with line managers’ real capability to properly execute it, can actually reveal to be crucial

for the successful implementation of performance-related pay schemes. Their failure is in

fact all too often due to lack of understanding or acceptance both of the pre-set

objectives and of the way these have to be measured. Yet, as anticipated above,

performance appraisal systems directly linked to performance pay and performance-

related pay approaches exclusively relying on financial reward are amongst the most

recurring causes for these schemes failure (de Silva, 1998). Providing individuals

opportunities for personal growth, training and involvement, enable employees to

expand their skills and capabilities, become more confident and hence perform at higher

level and more effectively contribute to the achievement of the organizational objectives.

An additional important implication of these arrangements is represented by the more

relaxed approach to recruitment it may enable employers to adopt. Firms having

recourse to performance-related pay schemes tend to offer relatively more modest fixed

salary in that the variable part of it, that is, that which needs to be re-earned, is

depending on the organizational, individual and team results. In terms of personnel

budget this implies that under a performance-related pay scheme employers normally

pay lower fixed costs. The personnel budget is consequently increased only whether and

when the organizational objectives are met, but in this case the profits made by

employers will enable them to face the increased personnel costs without any particular

difficulty. All of that accounts for employers being able to speed up the decision-making

process whenever the need to recruit additional employees should arise.

This open approach to recruitment, nonetheless, is not completely free of drawbacks.

The circumstance that employers may have recourse to a larger workforce in order to

292

Variable reward schemes

achieve their intended objectives would also consequently entail that the increased

reward budget, letting profit share unchanged, should be divided amongst a larger

number of employees; contracting, hence, the amount of the salary or bonus individuals

would have received whether the total number of employees would have been kept

stable.

Whereas these arrangements can enable employers to recruit a larger number of

employees thanks to the reduced impact this would produce on the personnel budget, on

the other hand employers should not overlook that this practice may cause in turn a rise

of the overheads by reason of, for instance, facility and office space increased needs.

The reduction of the fixed personnel costs associated with this approach can also enable

employers to less frequently or less immediately be prompted to make decisions about

making staff redundant when experiencing hardships, for instance, by reason of

slowdown and downturn periods.

From the personnel costs point of view, these are due to increase when performance and

profit will so that it can be maintained that these arrangements are to this extent self-

financed. As argued by de Silva (1998), such mechanism can also contribute to make

employees aware of their businesses fortune and misfortune and contribute to

individuals’ identification with the organization.

Findings of an empirical study carried out in the Netherlands (Gielen et al, 2006)

revealed that the introduction of performance-related schemes have a robust and direct

positive impact over labour productivity (9 per cent). Supporting many of the

conclusions reached above, the study also revealed that this increased level of

productivity did not bring any contraction on businesses recruitment activities; on the

contrary, the study also revealed that a 5 per cent long term employment growth was

associated with the performance-related pay method introduction. The Authors also

report a substantial increase of these arrangements popularity amongst Dutch firms,

which they acknowledge not being however related to a widespread confidence amongst

employers in the positive role played by this approach over productivity (Gielen et al,

2006). Nonetheless, the rate of Dutch organizations having recourse to these

programmes has actually increased from 29 per cent in 1995 to 51 per cent in 2001 (the

investigation covered organizations with more than 100 employees), with the most

remarkable growth recorded within construction organizations (+55 per cent).

Performance-related pay design and implementation phases

Once organizational objectives have been defined and the assessment of the conditions

for these arrangements introduction carried out, managers have to start identifying the

objectives to be potentially set for each of their direct reports involved in the scheme

with whom these will subsequently be discussed and agreed.

At this stage it is crucial ensuring that the likely goals can be all objectively measured,

reviewed and assessed. Once this step has been carefully and thoroughly carried out,

employers can openly communicate to their staff the mechanism of the scheme. Aim of

293

Variable reward schemes

this activity is to ensure that every individual concerned has crystal clear ideas about

what performance-related pay is, how it actually works and how it will be operated by

the organization and its line managers.

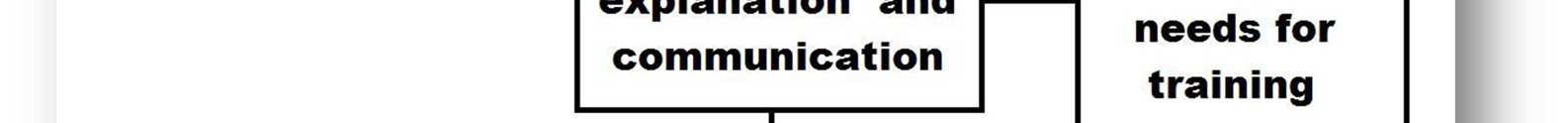

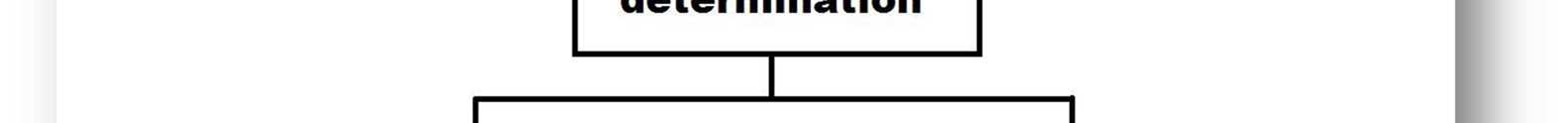

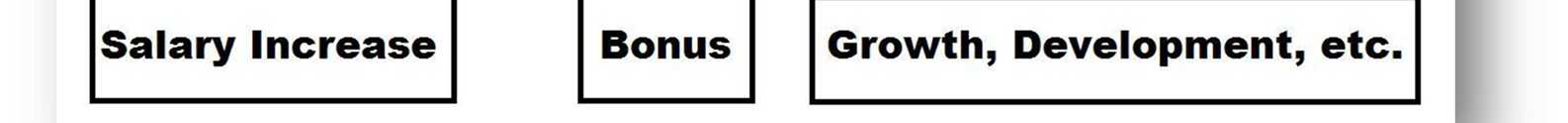

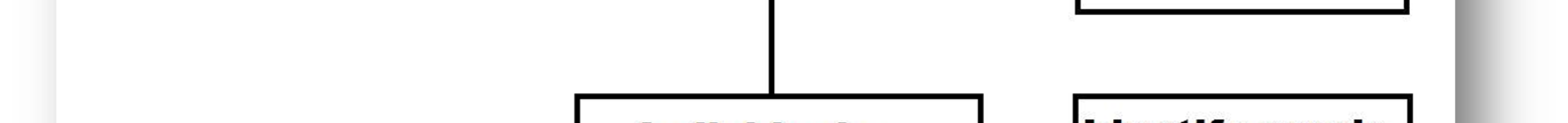

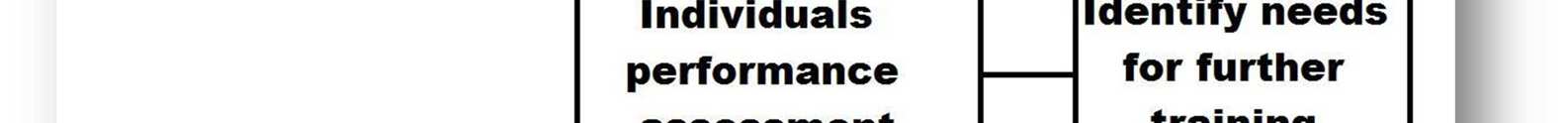

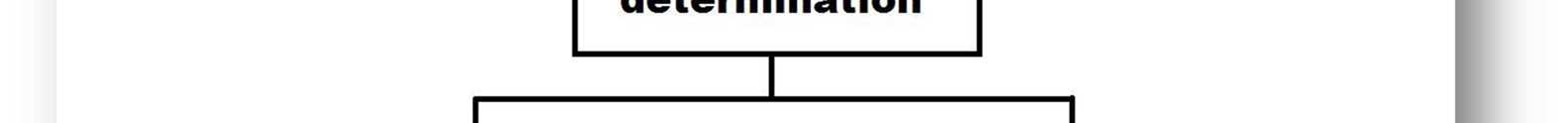

Table 38 – Performance-related pay schemes design and implementation phases

294

Variable reward schemes

Once the measurement methodologies have been determined and the scheme has been

explained to staff, managers can discuss and agree with their reports their individual

objectives. In this occasion, if required, further explanations about the scheme can be

provided to employees and, most importantly, managers can discuss with individuals

whether these have the skills and capabilities necessary to attain the expected results.

In the event this should turn not to be the case, managers will decide and plan with the

individuals concerned the bespoke training programmes necessary to bridge the

eventually emerged gap.

Line managers will clearly be trained to properly manage and handle the scheme before

this stage is actually executed.

At the pre-identified frequency, individual performance will be assessed and the eventual

need for further training evaluated by managers. At this point in the process, managers

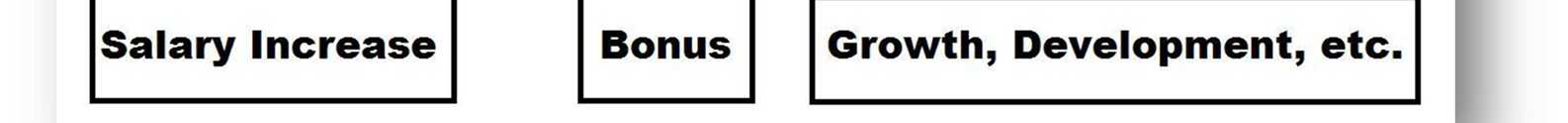

will be able to make decisions about the financial and non-financial rewards to be offered

to employees.

Financial rewards can be offered either in the form of a salary increase or a lump sum

(bonus) or a combination of both. Non-financial rewards will be mostly offered in the

form of opportunity for personal and professional growth and career advancement.

Training is once again very likely to come to play, but not with the intent of enabling

individuals to more properly fill their current positions, but rather to prepare employees

to manage more complex tasks and be able to fill roles encompassing broader

responsibilities in the future. This plan of action can also clearly be considered as a part

of a succession planning strategy.

Performance-related pay and the public sector

The outcomes produced by the introduction of performance-related pay schemes in

public sector organizations at large are not that different from those produced by its

introduction in private sector firms: sometimes the results are positive, whereas in some

others cases the method fails to produce the expected results.

Notwithstanding, some specific and peculiar features typical of this sector can actually

sometimes account for its implementation failure.

As argued by Behn (2004), in order to design and effectually implement a performance-

related pay scheme, public sector employers should care about a lot of details which

actually “matter a lot.” Constraints, both in terms of perceptions and expenditures,

imposed by citizens on governments contribute to make it even harder for public sector

employers introducing performance-related pay schemes whose details could be

considered even close to the ideal ones.

Furthermore, the reward aspect of employee relations within public sector organizations

has also become growingly harder to manage in an ever changing world where public

sector employers are increasingly engaging in competition with private sector

organizations and where the myth of a job for life is destined to completely vanish.

295

Variable reward schemes

The current state of play is actually characterized by contrasting needs and

circumstances. On the one hand public sector organizations tend to abandon rewarding

systems exclusively based on length of service, whilst on the other hand budget

constraints makes it harder favouring a smooth transition to effective and consistent

reward systems based on meritocracy.

There are indeed some good reasons for public employers aiming at introducing and

developing performance-related pay schemes within their organizations. Among them,

one of the most important is surely represented by the need for employers to increase

the number of valuable alternatives these can have recourse to in order to motivate and

retain quality staff. For decades, the only solution public employers could use to grant

their staff salary increases has been actually exclusively represented by career

advancement.

Moreover, by reason of the increased competition with private sector organizations, it is

becoming the more and more important for public sector employers introducing reward

schemes enabling them to attract more “dynamic and risk-taking” talents from the

private sector (OECD, 2005).

Like in the case of the private sector, performance-related pay schemes offer interesting

opportunities to public sector employers in term of cost containment. By means of these

arrangements employers can abandon pay systems essentially based on automatic

salary progression and start offering individuals pay increases exclusively based on the

outcomes these produce.

The introduction of performance-related pay schemes within public sector organizations

can also be supported by a sound political reason, namely to disprove the myth that

public employees are overpaid and that all of them are bad performers. The introduction

of such arrangements can provide externally, and indeed internally, evidence that also

the civil servants work is monitored and that the results produced by these are

constantly assessed and evaluated (OECD, 2005).

The governments which pioneered performance-related pay schemes introduction in any

forms, in 1980s, were Canada, Denmark, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Spain, Sweden,

the United Kingdom and the United States. A second wage started in the early 1990s in

Australia, Finland, Ireland and Italy; whereas from the early to mid-2000s these

arrangements were introduced in Germany, France, South Korea, Switzerland, Czech

Republic, Hungary, Poland and the Slovak Republic. By the mid of 2000s more than two-

thirds of OECD governments had introduced, at least in part of their public services, a

performance-related pay scheme; even though it must be said that in many cases what

it is defined in writing as a performance-related pay scheme practically fails to have

consistent pay link with performance (OECD, 2005).

Also in the public sector, like in the private, monitoring and assessing performance

represents a sorely tricky feat to achieve, not least because of the difficulty of identifying

296

Variable reward schemes

objective, measurable, consistent parameters and indicators. The most recurrent criteria

used to measure civil servants performance are:

Results achieved, assessed against the pre-set objectives;

Technical skills;

Competencies;

Interpersonal skills;

Teamwork capabilities;

Leadership and management skills.

More recently, some countries have introduced less traditional and, to some extent,

more stimulating indicators such as ethics (Canada) and innovation (Denmark) (OECD,

2005).

As anticipated earlier, in order to these schemes being successful, employers need to

care about a lot of crucially important details, which accounts in turn for these schemes

requiring remarkably huge resources. Regrettably, this circumstance is all too often

underestimated by employers, hence the predictable failure of many projects.

The introduction of performance-related pay arrangements can sometimes be subject to

a self-financing clause which, amongst the available options, can be more immediately

attained reducing worst performers’ base salary. Such an approach has actually been

introduced in Switzerland where civil servants having been rated “B” (rating attributed to

employees who have partially achieved their pre-identified objectives) see their salary

reduced to 94 per cent of the relevant pay band ceiling, after a period of two years

(OECD, 2005).

In some countries the savings achieved are shared amongst the staff. In Finland, for

instance, one third of the savings attained by public organizations is shared amongst the

employees.

Some empirical studies carried out within the public sector organizations have revealed

that performance-related pay schemes actually motivate to work beyond the usual job

requirements just a tiny percentage of staff; in many cases this approach also revealed

to be divisive.

Reportedly, another substantial cause for performance-related pay failure within public

sector organizations is associated with the importance individuals give to base salary,

rather than to variable pay. As suggested by Behn (2004), the incentives offered by

public sectors employers are habitually so modest that individuals might find it better

taking a weekend job at a shopping mall in order to receive the same, or even a larger,

amount of money. In this way they will receive the sum of money more quickly and

more certainly, although it would mean working during all the week long and clearly not

being involved in a compelling activity.

A study carried out by Prentice et al (2007) identified a proportionate correspondence

between employees response to performance-related pay schemes introduction and

297

Variable reward schemes

discretionary behaviour, with the degree of response actually dependent on the extent of

the financial benefits provided by the scheme, that is, a small financial increase produces

a small positive reaction (albeit a positive reaction is identified).

Research also reveals that the introduction within public sector organizations of

performance-related pay arrangements is most likely to favour and provide opportunities

for organizational changes, rather than for increase motivation within staff. The changes

required to introduce these arrangements are basically likely to influence motivation

more than the implementation of the schemes (OECD, 2005).

Research within public sector organizations also seems to support the findings of the

studies carried out within private sector firms as for what concerns the positive effects of

performance-related pay on recruitment. Denmark, Finland and Sweden, for instance,

have all reported of having availed themselves of these schemes introduction to this

extent. In Denmark, more in particular, 57 per cent of managers have claimed that the

introduction of performance-related pay schemes has enabled them to expand their

recruitment offer. Similar findings have emerged in studies carried out in England and

Wales, where performance-related pay schemes revealed to be an effective means to

attract and retain quality teachers (OECD, 2005). The findings of the empirical studies

carried out by Atkinson et al (2004) in England have also revealed that the introduction

of these arrangements has produced a distinct positive impact on teachers’ performance.

The positive results attained by the UK government as a consequence of the introduction

of some collective performance-related pay schemes, has prompted the government to

more widely foster this approach. A number of investigations carried out within the

public sector suggest that, by and large, the development of collective approaches to

performance-related pay produces more positive results than those yielded by

individualised approaches (OECD, 2005).

As claimed by Makinson (2000), in order to financial incentives being likely to produce

some effects, these have to be at least equal or above 5 per cent of base salary and, in

any case, above the current inflation level.

Empirical research suggests that also the contextual factor has an impact on the

outcome of performance-related pay introduction within the public sector organizations.

Whilst, for instance, results can be deemed positive within the medical sector (Andersen,

2007; Dowling and Richardson 1997; Hutchison et al. 1996; Kouides et al. 1998; Shaw

et al. 2003), research reveals that these arrangements are considered divisive when

introduced within the regulatory and financial sectors (Bertelli, 2006 and Marsden, 2004).

In some circumstances, such as the case of nurses, the motivational “public service

ethos” could even be jeopardised by the introduction of these arrangements. It is also

argued that in such context performance-related pay can encourage staff to work more

effectively rather than harder (CIPD, 2012).

With the exception of the studies carried out within the UK, some other investigations

revealed that performance-related pay schemes within the education sector are

298

Variable reward schemes

producing negative results on staff motivation (Andersen and Pallesen, 2008 and <