5 Inclusive Business (Holism)

Sustainability

Instead of following many other authors in discussing the true nature of sustainable development, our approach aims, ultimately, to transform the drive for sustainable development into a concept of sustainable performance. Brundtland (1987) in what was, if not the first then certainly the most influential definition, set out sustainable development as: development seeking to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. This Brundtland definition introduces at least three dimensions: the economy, the ecology and the society, and it suggests that they are interconnected. It furthermore introduces a time and a space dimension, and it raises a governing issue. By introducing space and time as variables in the equation, Brundtland has introduced a paradox in managerial thinking. The classical Newtonian view on management cannot cope with a moving and integrated space-time concept. From that perspective, as long as the society and the economy move slowly, one can make a fixed time-space approximation. That era is over. The complexity of the world (its non-linear and dynamic character) combined with the speed of change, no longer allows for non-linear static approximations. Classical metrics fail and the thermometer becomes the disease itself.

The Brundtland definition introduces the paradox of the short term versus the long term. Short term efficiency is required in order to remain attractive to shareholders; at the same time a longer term sustainability orientation is needed in order to be attractive to the stakeholders. Paradoxes enforce choices; choices and balances between different and sometimes orthogonal interests. Another paradox that Brundtland reinforces and which is not new is the paradox between reductionism and holism. Classical managerial approaches mainly, if not exclusively, focus on financial performance: the so-called “bottom-line”. With the Brundtland definition’s introduction of extra dimensions – for example, societal, ecological, temporal and spatial – no reductionist approach is up to the task of helping a manager answer the issues raised by the massively increased complexity.

Nevertheless, attempts have been made. One example was to introduce the concept of corporate social responsibility and then request reports on the company’s responsibility. Companies have also been required to report on their ecological footprint and, ultimately, may be held responsible for being ecological y neutral, and may even have to “pay” for their carbon emission rights. This again turns responsibility (a value) into an economic good that can be traded as an emotionless economic good. It doesn’t matter if a company pol utes, as long as they pay for it. That opens the way for countries who are willing to sell their “non-production” of carbon emission, to get some money for their economic development, just as there is a market for healthy third world body parts, such as kidneys, for wealthy recipients in richer economies. From a holistic perspective, needless to stress, this only shuffles the problems around and, as usual, it ends up in the laps of the powerless. A reductionist approach to sustainability, responsibility, and even ethics, will only lead to displacements, not to solutions.

Participants in the Global Compact Summit can sell off the carbon emission that they cause in the process of flying to the summit. When are we going to use video conferencing and, in so doing, open up such a summit to all those that are economical y unable to attend? Why do we still organize higher education at certain localities for the happy few that can make it and afford it, and leave out millions of people who are struggling to get education and, through education, development and growth? The technology is available; it is an issue of choice. Within a reductionist frame, a reductionist answer is offered: make “misbehavior” an economic good. On the assumption that everything can be reduced, assume that everything is an economic good and therefore anything can be commercialized. But can responsibility simply be diminished to the status of an economic good?

Global Compact principles

The Global Compact is a program started by the former Secretary General of the UN, Kofi Annan, at the Davos Summit in 1999. It is (in the words of the Global Compact program itself) a framework for businesses that are committed to aligning their operations and strategies with ten universal y accepted principles in the areas of human rights, labour, the environment and anti-corruption.

As the world’s largest global corporate citizenship initiative, the Global Compact is first and foremost concerned with exhibiting and building the social legitimacy of business and markets. The program accepts that business, trade and investment are essential pil ars for prosperity and peace. But in many areas, business is too often linked with serious dilemmas – for example, exploitative practices, different forms of corruption, income equality, and barriers that discourage innovation and entrepreneurship. On the other hand, responsible business practices could, in many ways, build trust and social capital, and contribute to broad-based development and sustainable markets.

The ten principles of Global Compact are the following ones:

Human Rights

• Principle 1: Businesses should support and respect the protection of international y proclaimed human rights;

• Principle 2: make sure that they are not complicit in human rights abuses.

Labour Standards

• Principle 3: Businesses should uphold the freedom of association and the effective recognition of the right to collective bargaining;

• Principle 4: the elimination of all forms of forced and compulsory labour;

• Principle 5: the effective abolition of child labour;

• Principle 6: the elimination of discrimination in respect of employment and occupation.

Environment

• Principle 7: Businesses should support a precautionary approach to environmental challenges;

• Principle 8: undertake initiatives to promote greater environmental responsibility;

• Principle 9: encourage the development and diffusion of environmental y friendly technologies.

Anti-Corruption

• Principle 10: Businesses should work against corruption in all its forms, including extortion and bribery.

The Global Compact is a purely voluntary initiative with two objectives:

• Mainstream the ten principles in business activities around the world

• Catalyze actions in support of UN goals

To achieve these objectives, the Global Compact offers facilitation and engagement through several mechanisms: Policy Dialogues, Learning, Country/Regional Networks, and Partnership Projects.

The Global Compact is not a regulatory instrument – it does not “police”, enforce or measure the behavior or actions of companies. Rather, the Global Compact relies on public accountability, transparency and the enlightened self-interest of companies, labour and civil society to initiate and share substantive action in pursuing the principles upon which the Global Compact is based.

The Global Compact is probably the one initiative of the UN oriented towards companies. It cooperates closely with the office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the United Nations Environment Program, the International Labour Organization, the United Nations Development Program, the United Nations Industrial Development Organization, and the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime.

The Global Compact claims to offer its participants the following benefits:

• Demonstrating leadership by advancing responsible corporate citizenship.

• Producing practical solutions to contemporary problems related to globalization, sustainable development and corporate responsibility in a multi-stakeholder context.

• Managing risks by taking a proactive stance on critical issues.

• Leveraging the UN’s global reach and convening power with governments, business, civil society and other stakeholders.

• Sharing good practices and learnings.

• Accessing the UN’s broad knowledge in development issues.

• Improving corporate/brand management, employee morale and productivity, and operational efficiencies.

Many companies have subscribed to the Global Compact and that in itself is encouraging. But even the voluntary support of a community program doesn’t necessary change a lot if the pressure for ruthless growth – with an adequately increased bottom line – remains the corporate credo.

As much as it is not difficult to grow if one doesn’t want to be sustainable, at the same time, it is not difficult to be sustainable without growth. The question, hence, becomes how to rethink growth. Growth in itself is not a problem. It should not be forgotten that entire regions and populations make legitimate claims for a decent development that in one way or another will include a certain type of growth. Such responsible growth will need a managerial approach of sustainable performance.

Inclusive business

The imperatives today, however, are further advanced and more so in emerging economies than in more mature markets. Porter and Kramer (2011) discuss the reinvention of capitalism in the Harvard Business Review: Times Have Changed. For them the bigger part of the problem lies with companies that still interpret value creation as optimizing short-term financial performance. This view overlooks the well-being of the customers, the viability of key suppliers and the economic distress of communities. They argue that business has to take the initiative to bring business and society together again. For them this is different from social responsibility, philanthropy or even sustainability; it is rather a new way of achieving economic success. They, however, still remain within the classical managerial paradigm, where there is little space for innovation around values, and bringing in wider societal needs. Within that paradigm, companies should focus on creating “shared value”, and not just profit. We argue in this book that this definitely needs another paradigm if it wants to go beyond the (rather conventional) self-interest of the company in all this. For them, the agenda remains company specific with a clear corporate (only) focus.

EABIS (European Academy of Business in Society) recently devoted a conference to “From Corporate Responsibility to Sustainable Business”. Perhaps we need to go beyond the concept of Sustainable Business and talk about “Inclusive Business” – business with a wider positive impact for al . Inclusive business can most likely only be values-based and values-driven. But in order to talk seriously about inclusive business, we have to touch on the prevailing paradigm. As someone said: we have squeezed out of the Anglo Saxon paradigm on responsibility what it has and it was not enough. Are we, business schools and business people, willing to explore a more inclusive paradigm?

When talking about inclusive business, consider some of the following situations. How can we organize supply chains in such a way that local (small) suppliers can play a role? Why do we still transport fresh food, fruit and vegetables from miles away where we most likely have local growers? This supply chain issue is of course true for any economic activity. Do we feel as a company a responsibility towards the development of local or small business? Another example is the concept of Sustainable Mining, whereby a mining house does not limit its activity and responsibility to the exploitation of the mine, but also contributes equal y to the development of the entire community around the mine. This should allow, with possible mine closure, that the community around the mine can continue its economic development. Can we consider that the mining house’s responsibility is not limited to the results of the mining operations, but equal y to the economic development of the community? Concerning the bottom of the pyramid, is it the idea that companies try to sell products to the bottom of the pyramid that are not made for that bottom, are entirely too expensive and not of real value added? Are companies taking responsibility for designing for the bottom of the pyramid and inventing franchising systems that fit the bottom of the pyramid?

As an aside, I feel that businesses have taken over from the business schools in this matter. Business schools no longer have the prerogative to create knowledge in this field. That is not bad per se, but it reinforces the necessity for much stronger cooperation between business schools and companies. The World Business Council for Sustainable Development (WBCSD) is just one example of this thought leadership.

As usual, the discussion at the EABIS conference focused on profit. But profit is not the issue. The problem is that business often is not inclusive. The driver is the inclusiveness, the values-based focus, and not the profit. But profit is what we need. And that brings us to the discussion about capitalism. Many would like to add something positive to capitalism (responsible capitalism, social capitalism, or whatever). For me, capitalism has everything to do with the ownership question and then we should not even talk about capitalism anymore, as Mintzberg says, “beyond Smith and Marx”. The discussion about capitalism is an historic one. Today, it is about the development of more innovative forms of inclusive business, like cooperatives (just to name one already very old form), community owned businesses and employee owned businesses.

Who is in charge? We are. We, business schools and businesses alike, should innovate our thinking in order to create social innovation and to eradicate poverty, inequality and exclusivity. A breakdown in the “social ecology” would be real y dangerous, and the tremendous inequalities in the world are a potential time bomb.

Dipak Jain, the dean of INSEAD, feels that the real danger today is inequality. We need to try and come up with a plan that benefits al . That focus forces us to train our students differently. We should pay attention to “Reflection” (where am I, what am I doing, where is my contribution), “Renewal” (how can I grow beyond myself) and “Responsibility” (on an individual level, and what leadership is all about).

Management students should know that they are a happy few in the world and by having this opportunity to study they take on a responsibility that goes beyond themselves. “To whom much was entrusted, of him more will be asked” (Luke 12:48 – The Bible).

In the shadow of the UN Summit on Sustainability, PRME (the Principles of Responsible Management Education, part of the UN Global Compact program) held its third academic summit in Rio in June 2012. An Inspirational Guide was launched where Business Schools that would like to engage with PRME can receive guidance and examples. It was encouraging to see that a growing community of Business Schools has become interested.

However, at the same time, the ever returning fundamental question remains: is it the individual who behaves unethical y and should it be individuals taking up their individual responsibility? Or are there other reasons to consider? If we can limit the misbehavior of individuals then Business Schools are not to blame and companies (or should I say “corporations”) are not to blame. We have saved the system and we do not have to ask some fundamental questions. We can add more courses on Ethics in Business or Sustainable Management Practice, but the rest is in the hands of individuals.

But is it realistic to think that an individual would not be part of a wider whole, a company for instance, or an economy, and that an individual, to a certain degree, is only part of a wider set of assumptions, indeed a paradigm? I feel that this is the correct discussion. What are our assumptions? What is the purpose of business? Are we interested in creating added value, other than what we return to shareholders? What is growth worth, if it would not be inclusive?

Denying the reality that people fit organizations liberates us from many interesting questions. It liberates us from being critical about what we teach, and it allows us to continue teaching tools and techniques instead of supporting the development of the “being” of the potential manager. It liberates us from challenging our linear, non-systemic assumptions about the economy. It liberates us from the discussion that we train for individual performance, and not for “us”, for cooperation, for inclusion. The student cohort present at the conference felt that they entered a business school with the best of intentions but were “brainwashed” (the word they used) for individual performance.

Isn’t it about culture, about tradition, about comfort and about the very fundamental paradigm of business that we have been supporting and teaching for the last few decades? Changing this will take time and effort, but do we have much choice? Can we continue the development of economies and emerging economies in the first place, based on a growing inequality between poor and rich, between unemployed and employed, between individuals and collective needs? It is not about us and them; it is about all of us being in the same boat. And we do not need great declarations of our governments or international bodies. What prevents us from starting tomorrow, in whatever jobs we have?

The lively debate between some politicians and the mining industry about the advantages and disadvantages of nationalization, as is currently raging in South Africa, is real y 30 years outdated. It is not wrong, nor it is not completely without meaning. It is just outdated. The world has changed. We are in 2013 and business as usual is just not good enough anymore.

The story is known for as long as I have been alive. Socialist oriented politicians (by the way this is not a South African issue only) believe that important industries need to be controlled by the “public” (which often means the cast of the politicians). Sounds fair: strategic importance, contribution to al , business has short term targets, etc. (By the way, most politicians have short term targets also, i.e. being re-elected in the coming few years). Anyway, we easily mix “public” with “politics” and the “greater good”. But history has not proven that these links exist. An alternative to nationalization, along the same lines of thinking, is a super-tax. The response from industry is the need for cash in order to invest (not sure this always happens by the way), but the track record of industry is not always one to encourage us to trust them to take care of the long term perspective, let alone the “greater good”. This debate can go on for decades (as it has), but it is a war on principles, nothing more.

We know from experience that nationalization seldom works and if there is still doubt just look at Zimbabwe. But more profoundly, there is not real y something like a “public” company or a “private” company. There are companies, that all follow the same basic logic of the working capital cycle (for each movement you should get out more cash than what you invested or eventual y you will go bankrupt). The ownership might be different, but the purpose should be the same: create added value, deliver something that society needs, and contribute to the development of the economy and its people. Some companies could target more economic value, some would target more social value, and some more societal value. Indeed, all companies should be value driven. This is not a new concept, but it has often been forgotten during the same 30 years of debate on nationalization.

And in classical (macro) economic theory, once wealth is created the government is there to take care of the fair distribution of that wealth, mainly by taxing and subsidizing. More mature economies (like Europe) show us every day where that can lead.

If we bring value, purpose, meaning, contribution and the like into the realm of the company (where it theoretical y should be anyway) then the issue of distribution is no longer a macro-economic issue, but it becomes a micro-economic one and indeed, we do not have the theories to deal with that. That is why academics need to develop fresh ideas around values-based leadership, social innovation, inclusive business, etc.

This is where inclusive business becomes center stage. If a company would indeed take its responsibility seriously, and would take care of community development (say around a mining site), develop youth (discover and develop leadership capacity in those communities), contribute to the creation of social businesses and work with local SME suppliers, provide healthcare for the workers, we would not need to discuss nationalization. The greater good would be taken care of.

A number of years ago I held the Philips Chair in Information and Communication Technologies at Nyenrode University in the Netherlands. An annual budget of a company like Philips is bigger than the budget of most of the African states together. Who do you talk to if you would like to have a fairer world? If Philips would build, with each plant they create, a school and a hospital, wouldn’t most of the problems be solved? And isn’t it the corporation’s responsibility to take care of the people working in and around the plant? Aren’t they the main stakeholders?

Companies should not replace governments, and governments are still there to take care of those that are not real y able to take part in the economic process (due to lack of education, health issues, social issues, etc.). For government, taking care means education, housing, social services and so forth. But companies should develop inclusive business, targeting the greater good of the communities within which they are installed and work with. The driver of business cannot only be value to shareholders. It should be contribution to the community and again, academics might contribute some thinking about how to measure that and how to manage that.

We can no longer hold on to “them-and-me” business thinking. The world has become complex and uncertain, and stil , certainly in Africa, has an unacceptably high degree of inequality. We are all in the same boat and other than changing our management paradigm into one of inclusive business, we might need to forge more public-private initiatives. Not to forget the potential for social entrepreneurship. Instead of continuing to pay 80,000 ZAR (US $10,000) for a house in a settlement, what prevents us from organizing a contest for the design of a 10,000 ZAR house (US $1,200)? Design for affordability, not for the ones that don’t need it. We still design 80% of our products for 10% of the people. When are we going to design 80% of the products for 80% of the people, affordable and responding to a real need? That would be interesting “Bottom of the Pyramid” thinking, instead of thinking how to market products to more people that don’t need it, and can’t afford it.

It is not about them and me, it is about us and about value creation.

Inclusive business cal s for a much more holistic understanding of business.

A holistic model

Holism is a term that is loosely defined and interpreted by many people in different ways. Is there a common notion of holism? Is there somebody who one day tried to compile all the theories? Perhaps it is evident that one should have all sorts of critiques here.

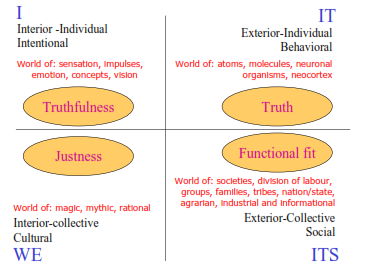

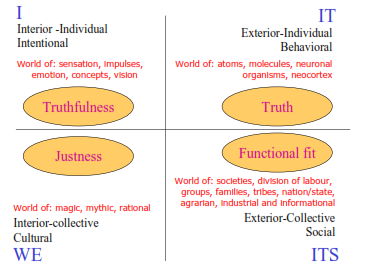

This chapter builds on one of Ken Wilber’s concepts. Wilber visualizes something that could be called different dimensions of the image of the holistic world. It is summarized in the following figure.

The figure is developed around two dichotomies: external-internal and individual-networked (collective). The top two quadrants make reference to the individual level. The bottom two quadrants refer to the collective level. The quadrants on the left have to do with the internalization of Man (or processes, or things), while the quadrants on the right examine, let us say, the mechanical part (the external). A holistic image is obtained, according to Wilber, if all the quadrants receive sufficient attention. He labels these quadrants the ‘I’ quadrant, the ‘We’ quadrant, the ‘It’ quadrant, the ‘Its’ quadrant. All the quadrants matter in order to achieve a life, an observation, a research, and a holistic interpretation.

In the top right quadrant, we study the external phenomena, for example, how the brain functions and so, natural y, reduce it to very specific parts such as atoms; classical reductionism. However, understanding the functioning of a specific atom does not necessarily allow us to understand the functioning of the whole (the consciousness of the human).

What we cal , at the heart of science, a global approach, is found in the lower right quadrant. However that is only one of the four dimensions of holism. Here, one can consider the systemic approaches (still mainly mechanical) of ecological concepts, sustainable development, etc.

To real y understand what the brain produces, requires attention to the left part of the diagram. In humans the brain causes: the emotions, feelings, concepts, etc. which are used in daily life.

No matter how detailed the understanding of the right part, it still says nothing about what a human thinks or feels. To get to the dimensions on the left, the classical approaches are insufficient. Communication is the only means to try to understand how people feel and what emotions they experience.

In the left part there is also a collective dimension: one could label it “culture”. That is related to what are accepted as groups, norms, and values. So a holistic understanding cannot bypass these internal individual and collective dimensions.

Classical science goes completely in search of the ‘truth’ (identified top right). More and more global approaches of the systemic in science appear as the functional whole. The true notion of Man and his emotions which we cal , a little paradoxical y, a “flesh and blood” man, does not give a real understanding of truth and fairness. That requires attention to the three other quadrants in order to provide a more complete understanding than the dominant thinking western culture allows. This book aims for a more holistic approach in management research and in the understanding of phenomena.

At the heart of each of the four quadrants we find a natural evolution from physics, via biology, psychology and theology, towards mysticism. Translated into the fundamentals, this goes from matter, via life, thinking, and the soul, towards the spirit. This demands a lot more explanation for which Wilber’s book is essential. In a crude summary, holism can be said to consist of an ensemble of ‘I’, ‘We’, ‘It’ and ‘Its’. This is quickly recognized in certain metaphors of holism, such as ‘Art meets science and spirituality’, the “I”, “We” and “It” of Wilber, or his ideas, could be expressed as saying that the hands, head and heart lead to holism.

A holistic model for business

Applying this holistic model of Wilber to management, describing companies and markets, within the context of the paradigm developed earlier in this book, we indeed describe the continuous non-linear and dynamic interaction of agents within a holistic concept. Business behavior is the outcome of such interaction. Business economics is the theory describing the reasons why this quantum interpretation should work, but equal y how it works (see Baets, 2006).

The quantum interpretation of business economics has three complementary foci: on the environment; on the company itself; and on people’s interaction. Translated to current business practice, they could be called: market behavior, management learning, and human interaction.

Market behavior describes the environment of the company, the context, the interaction that takes place in what we call markets. Markets are not necessarily physical markets. Even what are called physical markets consist, in part, of so-called virtual components. All players and influences are of course never physical y present in such a market. Policy is made and has an impact, without always being very explicit. In fact, market behavior involves talk about market and pricing interactions, out of which strategies emerge.

Management learning considers the company in its most essential processes (Baets, 2006): innovation and knowledge considered as learning processes. The move is from a control-oriented model, to developing and applying a learning-oriented process, especial y around innovation and knowledge. Both are essential for the longer term development of the company. Both innovation and knowledge management may need some supporting technical tools (like financial reporting, logistics, etc.). However, the latter are necessary, but not sufficient, elements of management. Those elements are easy to copy, can be described and easily optimized, and can therefore never become a real source of sustainable (profitable) development. It does not make them useless, but just as with the architect’s profession, it is not the tools that the architect uses that make the difference.

Human interaction of people (inside and outside your company) is probably the one complex resource that needs to be understood and careful y monitored. Human interaction needs to be understood as the potentiality of the interaction of people (agents) producing either individuals who co-create out of emergence (on the one extreme) or agents who cause a disastrous conflict (on the other extreme). The situation obtained is not what is important, but rather the process of potentiality and its evolution. Human interaction, just like management learning, might need some supporting techniques that are, however, never of a nature to replace the necessity to understand the i