II Know what your customer wants

Chapter 4 – Learn about and influence customer goals5

Customers don’t always know what they want. Or they may know what they want but not what they need. And they may have any number of half-baked ideas about how what they want should be implemented. That’s why you don’t just learn about customer goals, you also try to influence them in the direction of a better outcome for the customer. Your ability and willingness to help the customer find the best goals is part of the difference between being a so-so contractor and an outstanding one.

You are the contractor and the customer is the customer because you have knowledge and expertise the customer doesn’t have. If you are hired it is because you can do the job better than the customer, who may not be able to do it at all. And because the customer thinks you can do it better than anyone else. Out of respect for his opinion of you, you owe a duty to the customer to help get the best possible result.

But you can’t approach the customer as a know-it-all, because there are some things the customer knows better than you do, such as the everyday problems faced. Your customer knows, at least in general terms, why he or she thinks that something is needed that you can create. You must approach the customer with courtesy and respect. It’s the customer’s problem, after all. More importantly, it’s the customer’s money.

Customer needs must at some point be converted to formal statements of positive project goals. Then, the customer must consider what he or she is not willing to give up in achieving those positive goals. Those will be the cost, schedule, and other constraints that will be placed on the project. If your customer goes through these goal-setting steps without any input from you, and especially if competitors are providing input, the result may be a set of goals that you find difficult to live with. It may also be a set of goals nobody can live with. The result could be an unstable and failed project.

Paradoxically, by far the best time to ask a customer about goals is before awareness of them sets in. Consider the following hypothetical scenario.

-

Imagine that your company’s main focus is software and methods to “kill” computer viruses before they can do much damage, and to prevent their spread. You have a very large customer who has vast computer networks that occasionally are crippled by new viruses. While the new virus is being diagnosed, and your people are developing a “vaccine,” the virus spreads rapidly, infecting many of your customer’s computers and doing a lot of damage. One of your researchers notices that a “healthyl” computer’s communications across the network tend to be at a relatively sedate pace, while the communications of an “infected” computer tend to be frantic because the virus is trying to spread itself as rapidly as possible.

Your computer scientists develop a process that slows down communications when their rate rises above a certain threshold. The effect is that the virus is not stopped from communicating itself, but it cannot propagate itself nearly so rapidly. This provides more time for your computer scientists to diagnose the problem and find a cure before great damage is done.

Your business development people analyze the economic benefits of this process to your customer, and find that they are considerable. Indeed, they are so great that your customer can afford to subsidize the development of your new anti-virus software. So you develop project goals for the development and installation of the needed software and approach your customer with them.

Your customer did not have those goals before you brought them up. But once you did, your customer accepted not only your suggested positive goals, but also the negative cost aspects. In essence, your customer “bought” the whole package. Your competitors are pretty much excluded, so your win probability is close to 100%, as long as your customer is comfortable that your price is reasonable and affordable. And the careful cost / benefit analysis you gave him has already convinced him that it is.

Scenarios such as this are the ideal bidding situations. You don’t have to inquire into your customer’s goals, because you already know what they are. The goals came from your innovations. Starting with this situation as the best of all possible worlds, we can form the following hierarchy of difficulty to determine customer goals:

-

Pre-sold goals package. You propose an attractive solution for solving or at least mitigating a serious customer problem, or you enhance a customer opportunity. You provide both positive and negative goals that are convincingly realistic. Ideally, competitors are excluded because you have too much of a head start. Less ideally, one or more competitors may get up to speed fast enough to mount a challenge.6

-

Early goals shaping. By careful observation of clues dropped by a customer or potential customer, you become aware of a developing customer need just as the need is becoming apparent. You actively help the customer shape the goals, especially the positive ones, but you may also advise the customer on likely cost and schedule ranges to avoid the possibility that the customer may develop unaffordable goals. Ideally, you can do this and keep it hidden from competitors. More likely, alert competitors will sniff out what is happening and will offer the customer their own advice about what the goals should be. Or, the customer may simply want to see all of his options and will ask your competitors for information. You can’t always win a tug of war over what the goals should be. Your competitors may have better solutions than you can offer. But it is beneficial for you to be a player if your approach even comes close to being the best solution for the customer. Here are some reasons why:

-

Your unique capabilities are made visible to the customer, who may have need for them on other projects

-

The customer will be pleased that you are interested in helping solve his problems, even though you don’t have the best solution this time

-

Your participation may have made the customer more aware of the best mix of goals, making it more likely that the project will succeed

-

If the winning contractor performs poorly, you may be remembered as the contractor who “should have” gotten the work, and perhaps next time you will

-

Proposals, even losing ones, have internal value to you by sharpening your proposal skills and making you more aware of good directions for internal research and development

-

Late goals shaping. With little input from you or your competitors, the customer has done much internal work on determining the ideal goals. There may be competitive or security reasons for this state of affairs. When your competitors and you learn of the prospective bidding opportunity, the goals are already at least fairly mature. You have to go through an inquiry and learning process to understand the goals and your ability to meet them. You may still have opportunities to provide feedback to your prospective customer that may be useful in improving the goals and avoiding mistakes.

-

No goals shaping. Your potential customer, perhaps with the aid of one or more of your competitors, has arrived at a set of goals believed to be optimum. You have not been involved in shaping the goals, but must learn and understand them the best you can based on documents released by your prospective customer, and whatever conversations you can manage. You have to arrive at a decision as to whether you can be competitive given goals you did not help shape.

In the first of these scenarios, ease of understanding of your customer’s goals is greatest, and the amount of effort you have to expend to understand them is minimized. In the last scenario, the reverse is true. Understanding requires a learning curve, the possibility of misunderstanding is highest, and time pressures to produce a proposal may be extremely high. This argues that you always should be as near to the first scenario as you can get. Unfortunately, you can’t expect to always be in that scenario. Even with a competent and aggressive business development team, you are likely much of the time to wind up in one of the two middle scenarios. Given that, you need to be as skillful as you can be in dealing with already developed customer goals.

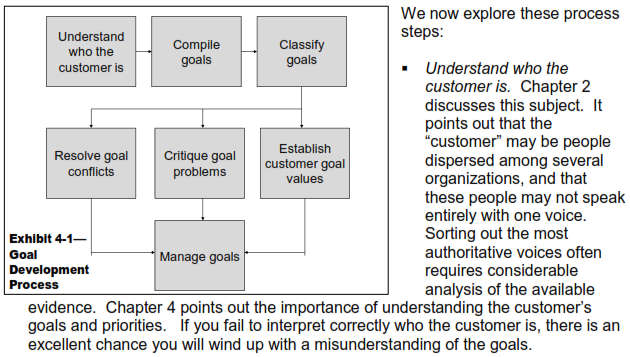

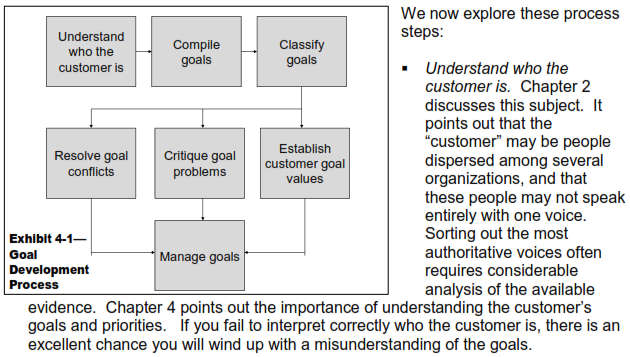

Because this is likely to happen from time to time, we believe it is best to follow a formal process for doing this. The reason is that it’s too important to be left to a haphazard effort that could lead to misunderstandings and mistakes. The process we suggest is depicted in the flow chart in Exhibit 4-1. In this chapter we will to a limited degree explore all of the steps shown, but some of them are more fully explained in earlier or later chapters.

-

Compile goals. Compiling the goals simply means bringing them together in one place in an organized and searchable format so that when you do further work on them you are sure to have all of them. Most goals will be in writing. Those that are not should be reduced to writing as soon as possible. With respect to valid oral goals, a wise course is to put them in writing and ask the customer to transmit them through formal contractual channels.

-

Classify goals. Requests for proposal in major projects may state literally hundreds of goals. They may be scattered throughout several thick documents. Some of them may ask for essentially the same thing but in slightly different language. Modern practice is to organize all goals whatever their source into a single computer database so they can be rapidly queried and so that related information can also be stored and accessed. Related information might include who is responsible for being sure the goal is met, the date meeting it was confirmed, and perhaps other information. In such databases, goals are often classified according to subject matter, importance, and other aspects.

-

Resolve goal conflicts. There are always tensions between positive and negative goals, but this is not what we mean by goal conflicts. Conflicts arise when two goals say to do different and irreconcilable things. If a negative goal says the project must be completed in 18 months for less than $10 million, that outcome may be highly improbable, but it is not a conflict. If it is merely improbable it is a risk. An example of a conflict is when one statement says that task A must be completed by a certain date and must use certain customer furnished equipment, yet another statement says that the customer furnished equipment will not be available until after the required completion date for task A. Another example of conflict would be when one statement says to paint something black, and another says to paint it white. Early resolution of goal conflicts is extremely important to project success. Resolution requires identification of the conflicts, then presenting them to the customer for action to clear the conflict. If we submit a proposal that is based on conflicting goals of which the customer is unaware, we run the risk of mistakenly being judged non-responsive by the customer.

-

Critique goal problems. Conflicts are only one potential problem with project goals. There are many others, such as lack of clarity, departure from reality, hidden agendas, etc. Probably the biggest potential problem with goals is when the customer’s expectations far exceed his budget. That subject is discussed in Chapter 6. The chapter discusses several types of mistakes often made by customers that you, as a contractor, should be able to recognize and help the customer avoid.

-

Establish customer goal values. Customers obviously don’t value all goals the same. This does not mean that you can meet only the most important ones and ignore the rest. If you expect to be a successful bidder, you must convince the customer you can meet all of them, even the relatively unimportant ones. But you should try to balance your efforts so that the bigger efforts go, more or less proportionally, to the most important goals. To be able to do this, you must understand how the customer regards the goals in terms of relative importance. Chapter 4 has a discussion of this subject.

-

Manage goals. Sometimes customers are very good at managing their goals. If they are, you will likely observe all of the following:

-

Goals will be stable. You will receive few changes in the request for proposal, and few changes in the contract once it is awarded

-

Goals will be internally consistent—no conflicts between positive goals and no conflicts between negative goals

-

Goals will be realistic. Tensions between positive and negative goals will not be unbearable, leading inevitably to project failure

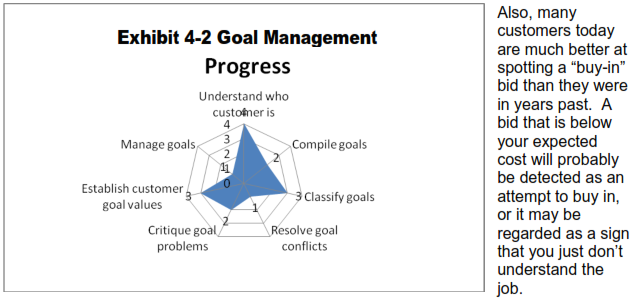

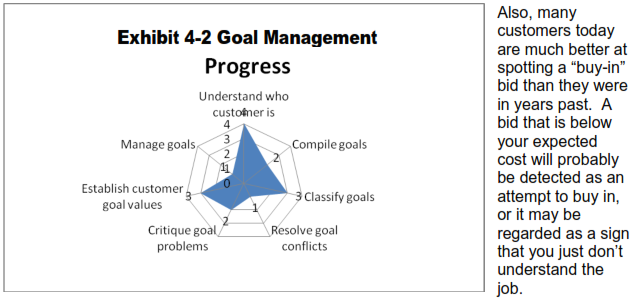

An excellent idea is to track the process of goal understanding in a manner well suited to management briefings. Exhibit 4-2 nearby is a good way to do that.

If the customer does not manage goals well, you will not observe one or more of the above. Let’s look at situations of poor goal management and consider what they might mean to you as a contractor.

Perversely, some contractors hope for goal instability. Their strategy is to bid at their expected cost or even below in order to assure a win, then they hope to become profitable by charging an exorbitantly high price for changes. We deplore this strategy. It is unethical. Moreover, it is dangerous. If the expected changes are not forthcoming, or if they are small, the contractor could lose serious money.

Conflicting goals are a sign that the customer may have problems with contractor management. At the least, it is a sign of carelessness. As previously noted, it is important that you point out goal conflicts to the customer and request their removal. Failure to do so can result in an unstable project that is prone to failure.

Realism of the goals has several aspects. One is technical possibility. Rarely will a customer be so grossly uninformed or careless as to ask for something that is literally impossible, but it is fairly common that a customer will ask for something very difficult that the budget will not support. Unrealistic goals are a frequent customer mistake. We should tactfully warn our customers away from such mistakes as a gesture of good will.

Customer visits during the pursuit cycle are vital in major projects. There is no substitute for face-to-face discussion to gain understanding and to minimize mistakes. Chapter 1 discusses a concept for an integrated business development team with membership from four areas of the contractor’s organization: top management, contracts, business development, and key technical people. All four areas should participate in customer visits. Here are some reasons why.

-

Top management visits demonstrate your commitment to helping the customer solve his problems. If problems need to be resolved, top managers by virtue of their authority can most often find fast and effective solutions.

-

Visits by senior contract administrators to their counterparts in the customer organization are an excellent way to minimize problems due to poor contract structure, unclear or oppressive reporting requirements, and the like. Such visits may also result in more favorable terms of payment, e.g., faster payment, lower withholds, etc., that increase return on investment. They may also help minimize risks due to late delivery of customer materials or facilities, or risks that these may not be well suited to the work or may be defective. A further useful service contract that administrators can provide is to help better define who the customer is and what is affordable for the customer.

-

Business development people must visit to detect possible beneficial expansion of the scope of work, or new bidding opportunities. Their visits also serve to make the customer more aware of what you have to offer and how the customer can best profit from it.

-

Visits from key technical people are vital to proper understanding of the customer’s technical problems and definition of the trade space. They can help eliminate inappropriate customer attempts to venture into problem solution, as opposed to problem definition. Often a key technical person can be instrumental in changing a difficult non-tradable goal into a less difficult tradable goal that you are better able to deal with. Visits by key technical people can also help your organization set better, more current priorities for internal research and development.

Chapter 4 Review Questions

1. How long has it been since your organization has pre-sold a goals package to a customer? Are you working to do that now?

2. In your current or most recent pursuit cycle, what efforts were made to influence customer goals? Was or is a competitor working to counter your influence?

3. Can you remember winning a project where you had little or nothing to do with shaping the goals? If so, why do you think you won?

4. Does your organization have a formal process for compiling and classifying goals? Is it effective?

5. Have you recently experienced a customer who had problems in managing his goals? What was the impact on the project?

Chapter 4 Bibliography

Ficalora & Cohen, 2010: Quality Function Deployment and Six Sigma: A QFD Handbook, Prentice Hall