Chapter 6: The Language of Work ModelTM: The Means to a Systematic Approach to Re/Org

The Language of Work ModelTM is introduced as a Re/OrgSystem that everyone in the enterprise can use together to organize or re/organize the enterprise. The Model makes possible alignment, transparency and continuous improvement.

Introducing an Operational Way to Align, Create Transparency and Achieve Continuous Improvement of Work

When employees, including executives, managers, workers, and team leaders, talk about, plan, suggest improvements, implement and generally communicate about work, there can be many problems. In fact, communication at work is a major reason firms employ consultants. A common, mutually understood and useful way to converse constructively about what work is (except perhaps technically) and how to improve it does not exist. It is as if we were all singing, but without a musical score to follow.

We might say there has been no formula or model of work that everyone shares to help you make informed decisions. Instead, you each use our own reference point about the work and assume that others share that point of view. Lacking a formula, executives talk about goals, objectives, strategies, products or services, while employees tend to talk about skills, knowledge, changes, activities and problems, as well as sure-fire solutions, and about executives who ignore these "obvious" panaceas. Chances are some are talking about one aspect of work while others talk, mentally see or under-stand other aspects: neither side is on the same page. Observe at your next meeting to see if this is the case.

Until now there has never been a universal "language of work" that centers communication, paints a clear picture of what work is composed of, and how the elements work (or don't work) together. No language has existed before that allows discussion, promotes consensus and facilitates clear understanding so as to eliminate subjective opinion while developing objective knowledge of the work and how to improve it.

To organize or re/organize a business at any level requires a universally understood and applied way to operationally plan and execute responsibilities, procedures and tasks across the entire workforce and management. Without it, re/organizing is left to guesswork, intuition, politics, personal agendas and posturing, leading to failure.

Thus far, you have learned how to think of a business as four levels of work execution: business unit, core processes, jobs and organization. You have also seen the need to support these levels with various kinds of organizational support for a healthy culture.

We now introduce an easily understood and easily applied Language of Work ModelTM in the form of six systemic elements that define each of the four levels and the organizational support layer of work. Using the same work model at every level allows us to align the levels and layer with one another and create greater understanding and clarity—transparency—up, down and across the enterprise.

Without such alignment, work is a jumbled mess of who's responsible for what and cries of "Why don't they support what we do?" Each department is managed as if it were its own kingdom, without regard to the overall mission and vision that maximize profit and customer satisfaction. Given the need for a common definition, understanding, and alignment of work, we can now describe the Language of Work ModelTM and how it can be applied to organize or re/organize enterprises the right way.

A Model of Work Everyone Can Use Together:

The Language of Work ModelTM

Enterprises, like the people who comprise them, exhibit behavior. Work behavior can be succinctly defined so that it is well understood by everyone in the company. When we are able to accurately describe or model the behavior, the best way to organize and manage it emerges.

The notion of everyone understanding and communicating what is or should be going on (correctly or incorrectly) is a relatively new concept in today's workplace. There will be more details later in the book on the possibility and value of full transparency after the introduction of the work model as it is used for re/organizing an enterprise, division, department or team. It is much harder to organize and run a company effectively and efficiently without everyone truly understanding their own and others' work as it relates to contributing to and ultimately achieving the overall ends of the business.

The work of an enterprise can be viewed as a systemic relationship between certain behavior elements that comprise work and then can be manipulated to the best ends of the business. This is roughly analogous to knowing the notes of a song so that all the musicians can sing or play individual parts and even develop new music. Using the same knowledge of the relationship, everyone can then understand what the work is supposed to be and, if it isn't, the right ways to improve the enterprise. There is no one better to make these suggestions and changes than those who do the work, and that is equally true for organizing the enterprise.

For our purposes in this book, everyone can engage in re/organizing the work—not just management. Management can find the best ways to meet their business circumstances and needs as an enterprise, but the workforce can tell us how to organize their work to those ends.

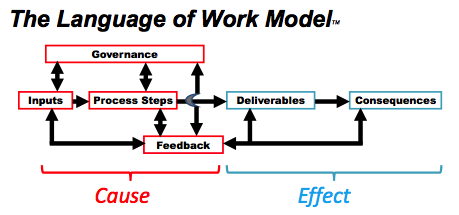

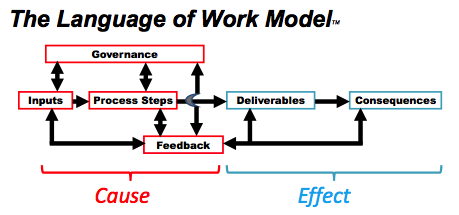

There are six interrelated elements that together comprise work behavior and can be used to define, align and organize work. The elements are presented here in two categories based on a cause-and-effect behavioral relationship. In this way, we will see what to produce (the effect) and how to achieve it (the cause).

In analyzing the work of a business, we must first know the intended results of the work and then how these results are achieved. In other words, we need to know the intended ends before we can determine how to achieve them. Thus, our behavioral relationship here is effect and cause. This is consistent with any good business practice. It says we need to know where we are going before determining how to get there.

We begin, therefore, with the desired effect—the end results we are trying to achieve in business work.

DESIRED EFFECT

... Something brought about by a cause or agent; a result

Business effect is composed of two interrelated behavior elements: deliverables and desired consequences.

Deliverables and Consequences

In work we want to achieve, as an effect, certain deliverables (behaviorally known as outputs) that will result in certain desired consequences (or benefits or value added). The deliverables the business desires to produce are commonly known as products and/or services. We produce or deliver these for the desired positive consequences such as profit, client satisfaction, return on investment, societal good, etc. If we begin by defining our desired deliverables—what products and/or services we want to deliver—and what desired consequences these will need to achieve, we establish the kind of business ends we want to have. There is another way to look at the same thing.

We could, conversely, define what desired consequences we want to achieve, and then what deliverables would help us meet those consequences. As a matter of practicality, which of these two elements is defined first or second is often an iterative activity designed to achieve as much clarity of intended business ends or effect as possible.

One business desires to produce hamburgers, while another has laptop computers as deliverables, and both desire certain consequences like those we have just stated: profits, customer satisfaction, return on investment, and so on. In the method of organizing or re/organizing a business, we will therefore begin the definition of work at each level (business unit, core processes, jobs and organization) by defining and aligning deliverables and consequences commensurate with that level of work, in relation to any previous levels already defined (e.g., how jobs relate to the core processes).

The question to be answered in defining or redefining the business after the desired effects have first been delineated, is what it would take to produce those effects. What does it take, from a purely work perspective, to produce the products/services—the deliverables—and the consequences?

CAUSE

... The producer of an effect or result

Business cause is composed of four interrelated behavioral elements: inputs, governances, process steps and feedback

Interrelated work elements that produce effects (deliverables and consequences) include inputs, governances, process steps and feedback. Together these four elements are the causes in a cause-and-effect relationship. Each of the four elements has a further systemic relationship to one another that produces the desired effects. Operationally, the model for work can be illustrated as follows:

The systemic relationship among these six elements of work can be summarized in the following operational descriptor:

Initiated by and using inputs (such as client need and available resources), under the influence of given or implied governances (rules and regulations), process steps are followed to produce/provide desired deliverables and their associated positive consequences, with the aid of a variety of feedback.

Note: In our various books and articles on the Language of Work ModelTM, we use a variety of terminology to designate work, such as: outputs for deliverables, conditions for governances and work support for organizational support. These have been relabeled here for simplicity and application by you and your enterprise. The original titles are consistent with a behavioral approach to communicating technically what work is and how the elements relate to one another—i.e., they serve my colleagues in the behavioral science world. Either set of words works well in any business setting and may be mixed and matched as they best communicate meaning and use in your particular setting.

In light of what we have learned thus far in this book, it would be accurate to also add that:

Work is best accomplished when the enterprise provides adequate organizational support to accomplish work execution.

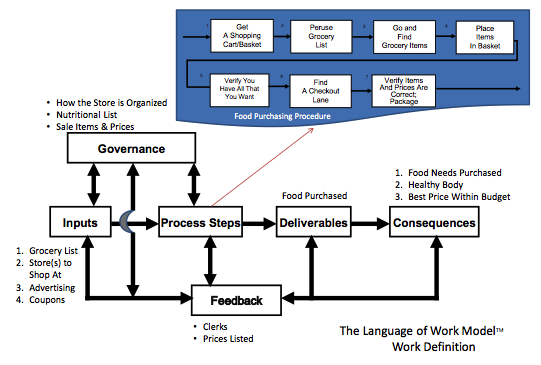

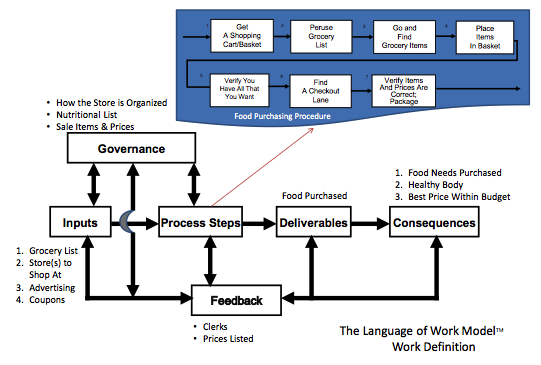

As depicted in the above illustration, the Language of Work is a behavioral model, not dissimilar to descriptions of everyday individual behavior. For example, buying food at the grocery store would be a typical output for the consequence of feeding yourself and your family. You bring with you a list of things to buy—your inputs. You have governances to follow, such as where the food is located in the store, perhaps your dietary needs, coupons, etc. Your process is to travel the aisles until you find items, put them in your basket and check out. You utilize or seek feedback in various forms of communication as you ask a clerk where to find the cottage cheese, read posted prices, use your smartphone, see whether a particular coupon is useful or not, or communicate with your spouse.

The six elements of work can similarly be used to explain what work is, or should be, going on in an enterprise at different levels. By using such a model with management and the workforce, we can define and agree on what the business is (its as-is state) or should be (its to-be state). The model can be an invaluable tool in making changes in the enterprise, which is the purpose of re/organizing.

Inputs

One kind of input of work is familiar and obvious to most of us: the resources used or needed to do the work. However, another kind of input may not seem so obvious, but it is always present, necessary and critical to business success. That is the input which initiates or triggers the work. Thus, when a customer says, "I want this," that is the trigger input to start work. Similarly when an executive, manager or other worker asks for something, it triggers work in the form of the answer to a question, a requested report, a specific task or set of tasks and so forth.

Governances

Governances are the rules and regulations that must be taken into account at all levels of work. These governances are kinds of "inputs" in one sense, but the difference between governances and inputs is that the governances are usually "fixed" (much like a rule or policy) and in place; thus you don't use them up as you do inputs; instead, you follow them. Governances may also be hard to change, but it is not always impossible to do so. Generally speaking you can't or really shouldn't change them yourself. In business you can ignore governances, but that really isn't that smart. Instead, you can learn what to do with them and influence how they might be used or changed.

These are the kinds of internal governances found in company policy manuals, as well as the rules from various external governing sources such as laws, regulations, union rules and so forth. Following OSHA rules on safety would be a good example. Governances commonly have influence over inputs used, process steps to be followed and even feedback.

In the grocery shopping illustration just cited, typical governances would include store layout, nutritional listings, return policies, use of coupons, etc.

Process Steps

Process steps, or processes, are the activity engaged in to produce the outputs or deliverables of work. When the input, such as a client request, presents itself, we initiate a series of actions to respond to or service the request. It may be a process that requires a repetitious set of steps or one or more sets of steps that allow workers to "create" the way the request will be accomplished. Process steps are what we commonly think of as the activity, the tasks, of doing work. When you divide that activity into its elements like inputs, conditions, process steps and feedback, it is much easier to see how to change, influence, improve, align, and for our purpose here, organize or re/organize work.

Feedback

Feedback includes the information that helps us do the work correctly, helps make us take corrective actions, reinforces us when we have done things right or shows us when we've done them wrong.

There are two broad forms of this feedback. The first we use while working, and the other occurs when the work is finished. Thus, there is a formative kind of feedback from managers, other workers, ourselves and clients that help us get the work done correctly and on time; here we can make mid-course corrections if needed. Summative feedback says we have done the work right, and the customer says they are satisfied (e.g., repeatedly purchasing our output). Or, conversely, the work output isn't exactly what they wanted and needs to be corrected in some way. Note that feedback is systemically related to the other five elements of work, as illustrated here:

Input: we correctly heard the customer's request

Process Steps: we completed the procedure the right way, or we have seen it needs to be adjusted

Governances: we followed the rules or regulations

Deliverables: we gave the customer the right product or service, as requested

Consequences: the customer says he is satisfied and pays us

You see then that feedback is systemically related to the other five elements of work. Feedback is perhaps the most overlooked element of work in business.

Examples of each of the six elements of the Language of Work ModelTM for the grocery purchasing example are summarized below. Note carefully how each element has a systemic cause-and-effect relationship to others.

The Language of Work Model(tm) serves as a backdrop for knowing how to define work behaviorally. With this in mind, we can now look at how it would be used to organize or re/organize an enterprise. In broad terms, this means we need to define and reach consensus on the four levels of work, as well as on how to support the work as an enterprise. This defining process or modeling, as you will come to know it, will lead to a deep knowledge of the business, and tell you how best to structure it.

First, we need to describe the meaning and importance of work alignment before we provide an example that illustrates how the Re/OrgSystem works.