Chapter 8: A Sample Re/Organization:

This chapter introduces a case study of an actual enterprise Re/Org. It is designed to acquaint the executives and other management with the essence of a re/org without the details. Details on a re/org, with sample documentation produced at each stage, can be seen in the other edition of this book. It is designed for those who will help you facilitate an actual re/org on your enterprise's behalf.

Achieving Work Alignment

This introductory sample of a re/org occurred in a major utility with a large IT function, Agua IT Services (AITS), a fictional name to preserve confidentiality. AITS has about 250 employees; its mission is to provide several services related to statewide water management, flood control, environmental concerns, agricultural and citizenry needs related to the transport and the availability of water statewide. The IT function alone interacts with more than 50 internal business units and provides a wide range of IT services for monitoring, conveying, protecting and maintaining the quality of water resources. AITS largely employs IT professionals, technicians, specialists and support personnel.

Note: Before or after this chapter you may wish to read the Case Study, AQUA, upon which the sample reorg described here is based. This case study is found in the Appendix. It provides additional details useful in further understanding what will be describe here.

First, Define the Business Unit:

The "WHAT"

To achieve organizational alignment (as well as transparency and continuous improvement), a re/org must begin with a clear understanding (especially among executives) of WHAT the enterprise is (its current state) or is to be (its future state). This should be obvious enough, since we all agree that knowing the goal is critical to achieving the goal. However, companies often grow in bits and pieces, or in spurts, which then leads to an absence of deep understanding of the work. An operational model to date—such as the Language of Work ModelTM—to define the "what" and reach consensus overcomes this deficiency of work understanding. For this reason, with rare exceptions, we must begin the re/org at the business unit level.

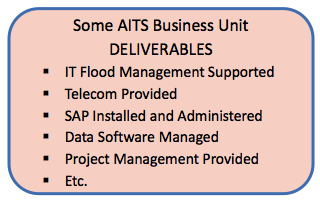

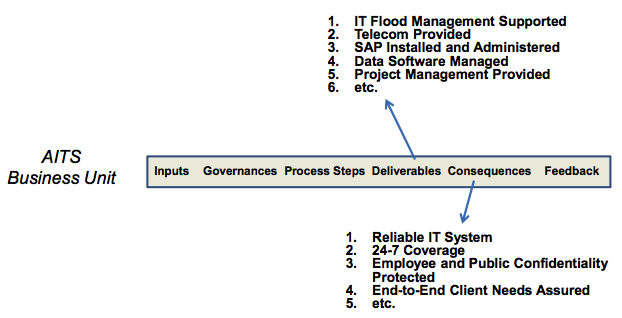

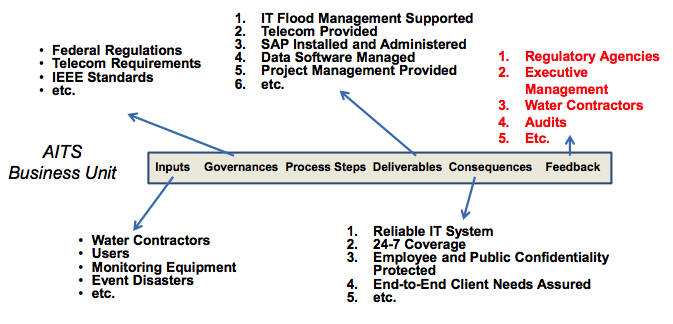

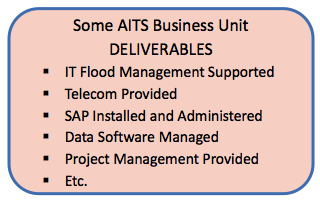

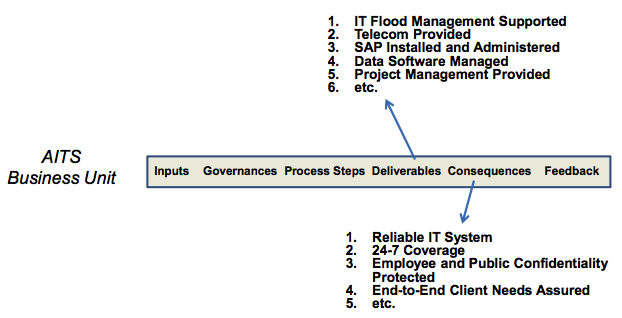

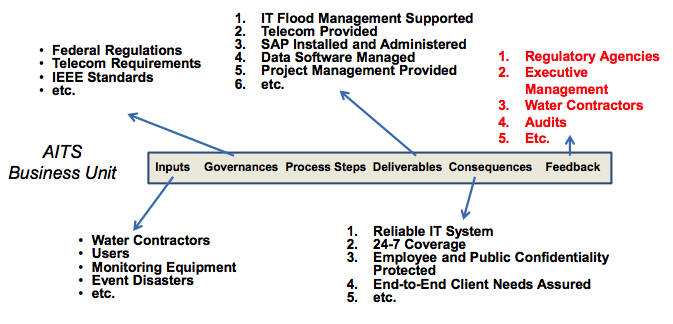

The AITS executive team formed for reorganizing the IT function began defining their business unit by identifying major deliverables. These are the major products and services that they "deliver" to their customers (mainly water contractors) and clients (internal business units, agricultural groups, and citizens). These are primarily services like IT Flood Management Support, Telecom Services, SAP Installation and Administration, Data Software Support, Project Management, and so forth. Most enterprises deliver 5 to 7 major deliverables, but there are exceptions. In the case of AITS, there were 10 major deliverables, a few of which are listed here:

Note to the chart: We are deliberately not listing all deliverables produced by AITS; instead, we are providing a few examples so that you can see the work-product without getting caught up in the details of a typical work model. If you want more detail, this may be found in the Appendix or in other sources, such as the many re/org engagements case studies available from the authors).

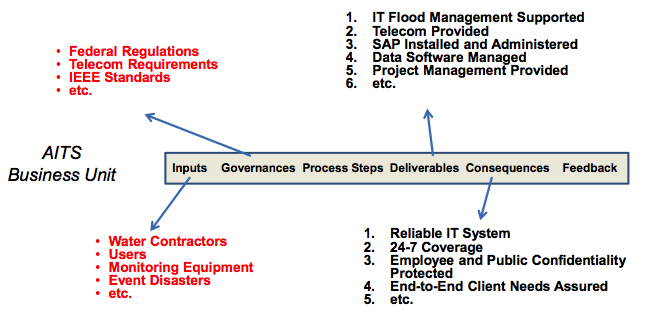

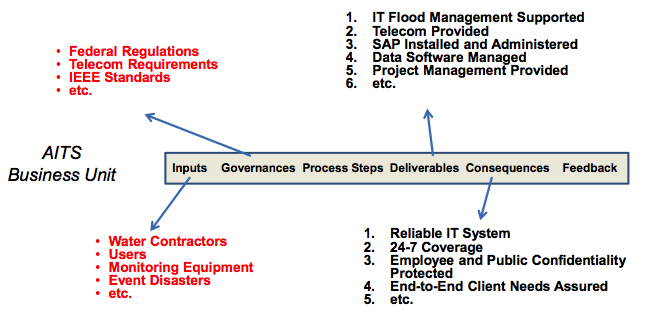

After the deliverables are defined, the business unit modeling team turns its attention to the desired consequences for AITS, answering the question, "What are the deliverables designed to be achieved as value-add?" Usually the consequences are pretty straightforward, and executives have little difficulty identifying them. They are expressed as value statements of desired business outcomes that include things like: reliable IT systems, 24-7 IT coverage, protection of employee and public confidentiality, satisfaction of end-to-end client needs, and so on. One of the ways to ensure that the desired consequences have all been identified is to cross-reference the consequences with the deliverables that should achieve them.

Note: This model is designed in such a way that, by using techniques such as cross- referencing deliverables with consequences, one is assured that all the deliverables have been named.

Because the Language of Work is a behavioral-systems model, adapted to the world of business, it is able to describe the work completely and quickly. One is not on a search for every little detail. Instead, the categories have been named, and the work of the experts is to populate those categories. While it is intellectually taxing to do so, because you must think outside the box, the set is defined and therefore self-limiting. In other words, following this modeling process develops a clear—and accurate—picture of the work of the business unit.

Any missing consequences, or for that matter incomplete deliverables, will be revealed by cross-checking, and missing refinements will emerge in the subsequent definition of process steps and other work elements. For the AITS business unit, (some of) the deliverables and consequences are summarized below, to which examples of the other work elements will be added shortly.

Note: This and subsequent illustrations are not the actual form of the Language of Work ModelTM, but rather are simplified representations for use in this book. See the appendix for an actual sample core process model. Other various models at different work levels are found in the Facilitator's Guide to the Language of Work Re/OrgSystem.

For AITS to achieve its desired deliverables and consequences as diagrammed above, they need the means to do so. In the Language of Work Model(tm), the "means" to achieve "effect" (which are the outputs and the consequences) is based on defining the four work elements: inputs, governances, process steps and feedback.

Looking at inputs first, remember that inputs are of two kinds. We see that AITS inputs include various kinds of client requests that trigger work, as well as a variety of resources which are needed to accomplish the processes, adhere to the governances and utilize the feedback. Trigger inputs articulate the initiators of the work; this is important because when these inputs are enhanced or improved, they directly impact the quality and/or amount of output. The more client requests there are, such as, in this case, from water contractors, the greater the quantity of (work) output should result. The other kinds of inputs, known as resources, identify what needs to be in place to produce and/or service the business outputs. Monitoring equipment would be one example of a resource input for AITS.

The enterprise business unit team next identifies the governances that need to be followed in doing its work as an enterprise. These are most often the rules, regulations and laws that must be followed. These are, so to speak, the "stay out of jail" elements of work. Federal regulations govern water resource utilization stringently in the case of AITS. Other examples (in red) of inputs and governances to the business unit model of AITS are listed below.

Once the deliverables, inputs, governances and consequences have been identified, the team modeling the business unit is now in a position to define the process steps at the business unit level, given that the inputs, under the governances, will produce the deliverables that achieve the consequences.

The business unit is most often an organizational depiction of process. The business unit's process steps will therefore be defined in a form different from the process steps of the other three levels of work execution. This is because the level of detail needed to achieve consensus of process steps at the business unit level is far less. Executives, for their part, are mostly interested in a high-level view of the business unit process. They don't need or desire details on work execution. When they eventually do need the details, these are available through other, subsequent work levels in core processes from some key work groups. Executives rarely need or want job-level performance information (with some key exceptions that need not be detailed here).

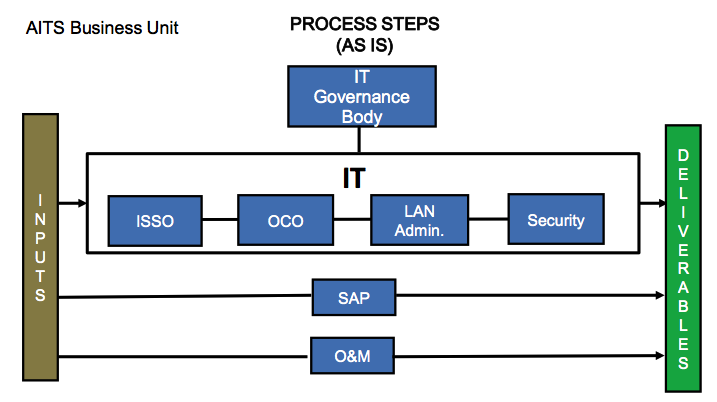

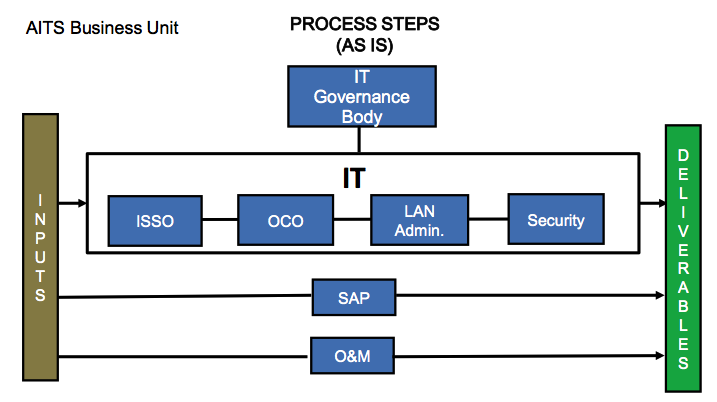

An illustration from the AITS business unit will adequately illustrate one—a primary, but not exclusive—version for expressing process steps in a business unit.

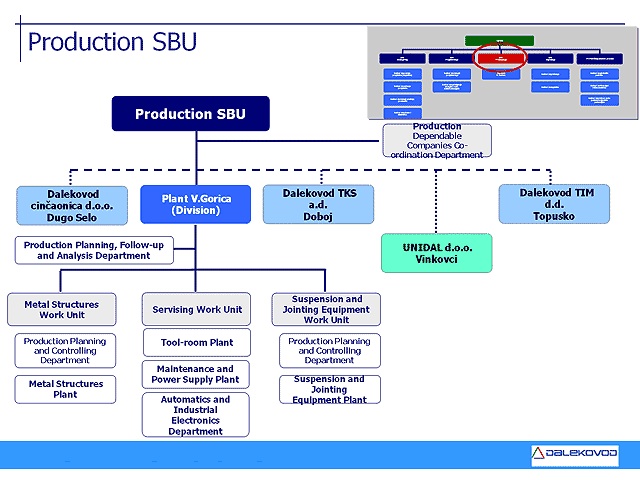

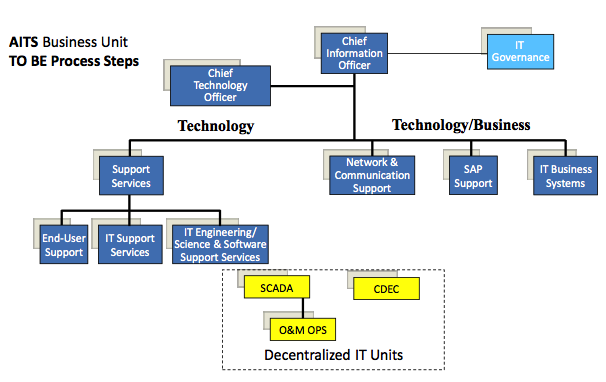

The process steps of the AITS business unit shown below illustrate how work is processed organizationally. This is fairly typical of how enterprises represent themselves. A chart illustrates the relationship of various work groups (departments, entities, etc.). This AITS chart, communicates how AITS views, from a process point of view, its major deliverables and consequences.

The depiction of the process steps of a business unit at this point in the re/org is merely a convenient organizational placeholder. It shows the current, AS IS, state of the process steps AITS uses as a business unit. In the Re/OrgSystem, the TO BE (future) state of a business unit process element will be the new re/org structure that results after alignment of work from business unit to core processes to jobs and finally to work groups. This TO BE process step won't exist until nearly the end of the entire re/org process. Only then can we be assured that the best re/organization for the enterprise is based on an alignment of the work, defined throughout the organization from one level to the next, which culminates in determination of work groups.

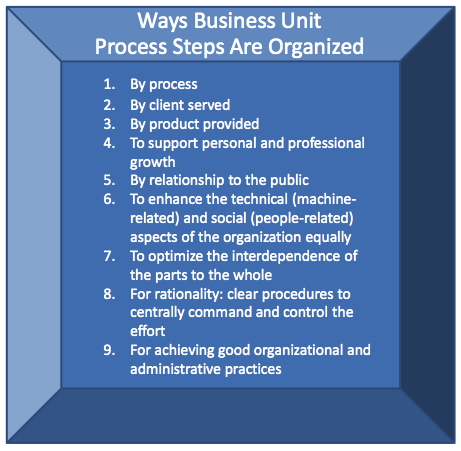

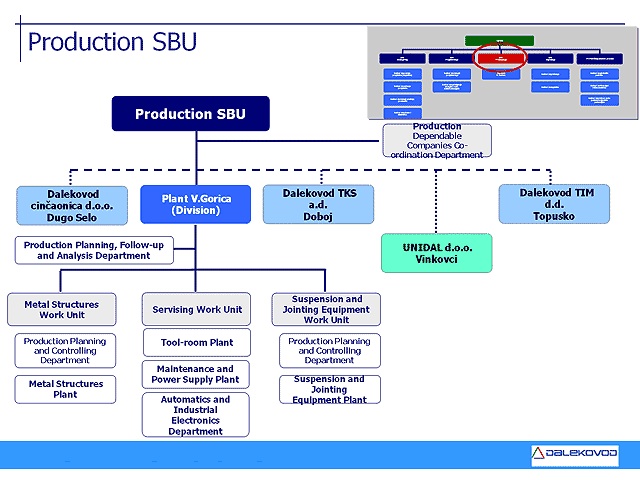

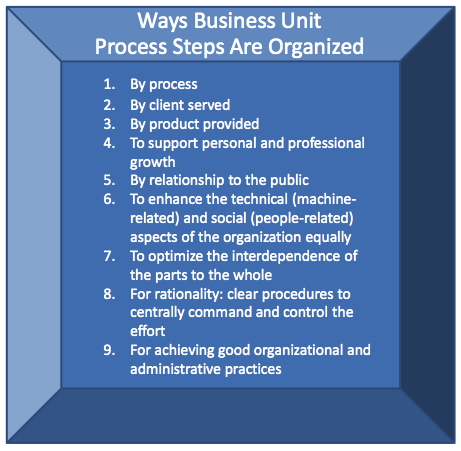

There are several ways to formulate a business unit process according to varying business needs. These ways are summarized in the following list.

Among these, the easiest and most often used is number 8, a perceived need for "clear procedures to centrally command and control the effort." This is reflected in the process steps in the AITS enterprise: it illustrates how all the various work groups relate to one another to produce the deliverables, using a hierarchical/military central command structure.

Still another way to represent process steps in a business unit is by the flow of different core processes—criteria one in the table of how business units are commonly organized. Thus, for example, the process of marketing flows into the processes of selling, delivering, billing and customer servicing. This would be an example of the business unit process steps in other enterprises. Regardless of which criteria you chose, the business unit modeling need at this point is to capture at a high-level view of how work flows to achieve the deliverables and consequences by using the inputs, adhering to governances, and aided by appropriate feedback. There is no need at this stage of modeling the business unit for lots of core process detail for each business deliverable.

Finally, we come to defining feedback as the sixth work element of a business unit model. At the business unit level, feedback is key to knowing that the organization is doing its work right and can make mid-course corrections when needed. Ultimately feedback ensures that the clients and customers receiving the deliverables are satisfied. Here are some typical examples of business-unit-level feedback for the AITS enterprise:

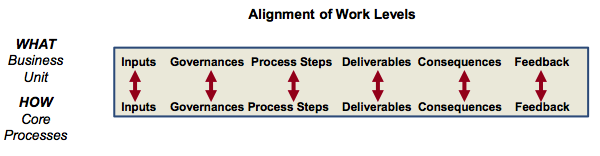

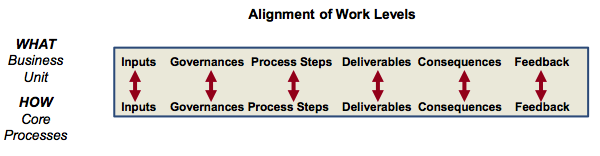

Thus, by way of a summary, the six elements of work are used to define and achieve an understanding and consensus of AITS at the business unit level. Business unit modeling by the executives achieves agreement on the WHAT of the business. This model sets the direction for communicating to everyone who follows in the re/org process exactly what the executives want the work of the enterprise to be. Others in the enterprise will then base their modeling of core processes, jobs, organization, and organizational support on this graphic understanding/modeling of the business unit.

Second, Define and Align Core Processes to the Business Unit:

The HOW

with the WHAT

With the business unit well-defined and shared with others for input, clarification, and consensus, the re/org moves next to modeling the core processes that are used to produce the products and services (deliverables) of the business unit. Here is where much of the detail, but still at a high level, begins to emerge as to how the work is to be done to achieve the major deliverables. This is done—and this is important—without general regard for WHO will actually do the work. As noted previously in the Language of Work approach, WHO comes at the third level of work modeling—the job level. WHO (individually) is obviously important, but to achieve alignment, the re/org must first define the optimal view of how the work is to be done. Otherwise it becomes confined by a lack of perceived talent or concerns about taking care of or finding a place for individuals. Be prepared to define core processes as if the world were your oyster, but realistically, given available technology and resources. Thinking outside the box when defining core processes can pay immense dividends to making work and the re/org all that much better.

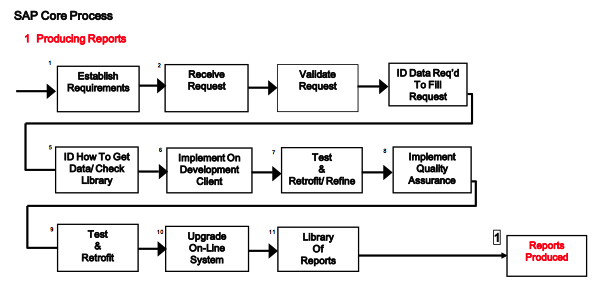

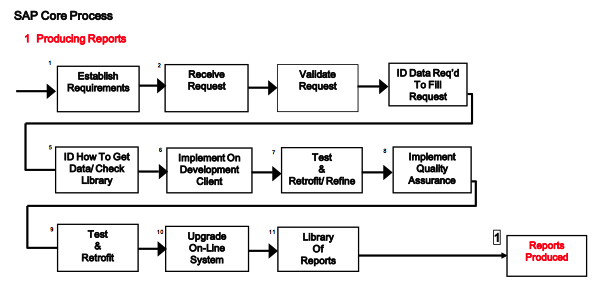

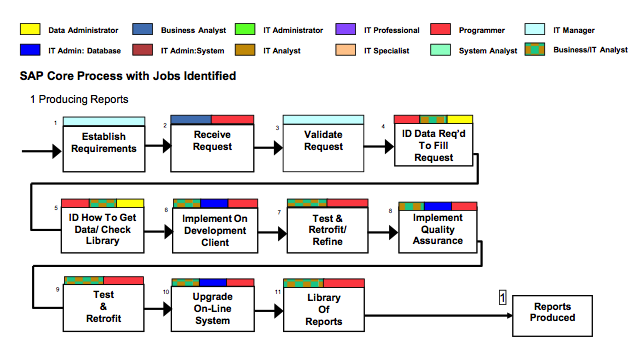

We will look the core process of AITS related to the output of SAP installed and administered, and within that core process, reports produced. Therefore, the corollary process name is producing reports.

Core processes are to be modeled by management at the operational level; usually by directors, managers and/or supervisory personnel—those whom everyone in the enterprise generally known for their expertise at the core process level. They usually have the respect of both the executive management and the workforce. You know who these people are. It is desirable for an exemplary job performer in a given core process to be included on the core process modeling team. Their perspective, as exemplary job performers, adds much value and often keeps the management personnel more realistic.

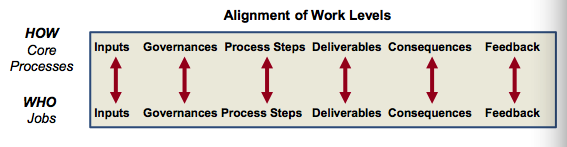

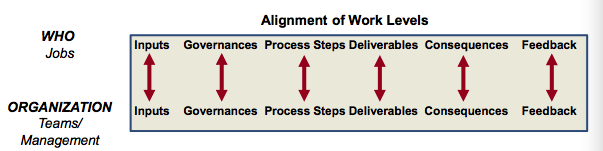

As we have noted, core processes represent the HOW of the business. They show HOW to produce the major deliverables that have been specified in the business unit model as the outputs. Since the Language of Work Model(tm) is used to define both business unit and core processes, the six elements of work in both can be precisely aligned with one another: outputs of business unit to outputs of core processes, inputs of business unit to inputs to core processes, and so forth for the other four elements of work. Of course, they will be defined at differing levels of detail, but they can and should be aligned. Not aligning the work in this way only places workgroups at odds with one another and creates great inefficiency or even conflict among workers and managers.

As was noted before, the modeling of core processes is done by your key managers and exemplary performers, under your sponsorship as the executive(s). They will define each model, preferably with a good facilitator. Your managers will be producing in this phase of the re/org process a clear, concise and consensus-based view on HOW this work will be done to align with your view of WHAT the business is. Together, you will have aligned the core procedure to the business unit so that everyone understands it and can move to the next step of WHO will do the work to achieve the HOW. The core process for producing reports, of SAP is illustrated as follows:

Third, Define Jobs and Align Them to the Core Processes:

The "WHO"

to the "HOW"

There is a maxim that goes: "Success depends on finding the right person for the right job!" A precursor of this maxim should be: "To get the right job, match all jobs to their related core processes." It's not enough to select the right person to implement a job role; it must be the right job for the work itself. This mismatch happens more often than you may think. But now there is a much more scientific way to place people in jobs than to turn over a list of specifications (dream team characteristics, perhaps?) to HR. Instead, by aligning jobs required to execute the core processes, you can be sure that you have defined the right jobs to fill.

The Language of Work solves the identification of jobs quite simply. Once the core processes have been modeled (as described in the second step,

Note: We have deliberately not shown throughout this book the completed modeling documents produced at the various levels of work so as to avoid letting content details of the sample enterprise get in the way of fundamental understanding of the Re/OrgSystem. However, should you want to see one example of such a model at the core process level, the Appendix does contains a typical core process model in its final form. You will find many other examples of models at all levels in the other edition of this book, The Facilitator's Guide to the Re/OrgSystem.

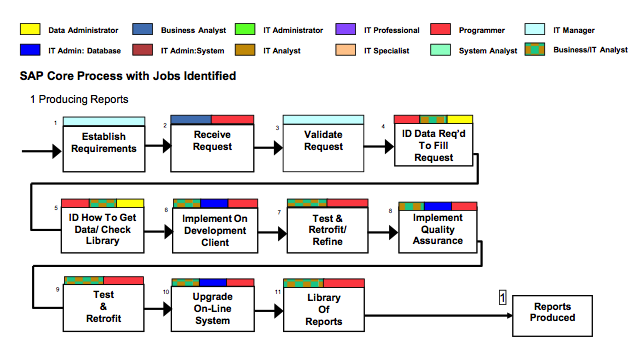

above), one can simply list the job titles that currently exist (and/or new job roles that are revealed from core process modeling), and color code these jobs to the process steps of the core processes. Below is a simplified illustration of how this looks relative to the sample SAP core process and the output that relates to producing reports:

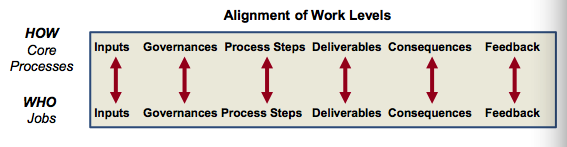

When modeling jobs using the Language of Work approach, existing job holders will not be left to decide for themselves (or by managers or HR only), what their jobs entail. Instead, each job will begin with an understanding of how the job fits into the core process of the organization. Because jobs are based operationally on the work needed to execute the well-defined and aligned core processes, through color-coding jobs to the core processes, each job can subsequently be modeled based on the actual work to be fulfilled. Use the Language of Work Model(tm) to model these jobs, with primary input coming from the core process models. Ordinary job descriptions cannot do this, because the relation of the job to the core process has not been linked. The alignment process of the Re/OrgSystem will help ensure that you have the right jobs for your core processes; then, and only then, will you be able to find the right person(s) to do the work consistently and well.

The six elements of the Language of Work Model(tm) can be used to define any job, no matter how simple or complex the work. Job models precisely connected to the six elements of work previously defined in the core processes and business unit are critical to a well-designed, well-aligned enterprise.

Fourth, Model and Align the Organization of Teams/Management

Work Groups Aligned to Jobs, Core Processes and the Business Unit

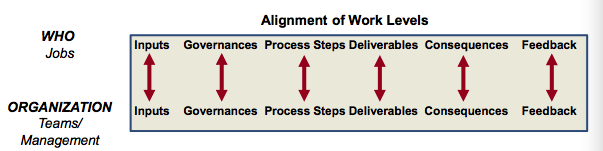

Individual job holders don't typically work in a vacuum. Rather, they work with other professionals, technicians and support staff, and with managers who help facilitate the work. Individual jobs need to be aligned with other related jobs in the enterprise. We refer to the jobs that relate to one another as the ORGANIZATION level of work execution; business usually calls them by names like teams, units, sections or departments. These are all one version or another of what we collectively label as work groups. One of greatest features of the Language of Work Model(tm) is that it provides the means to align work groups and management positions directly to the business unit, core processes and jobs. This creates unity in the work and eliminates disconnects.

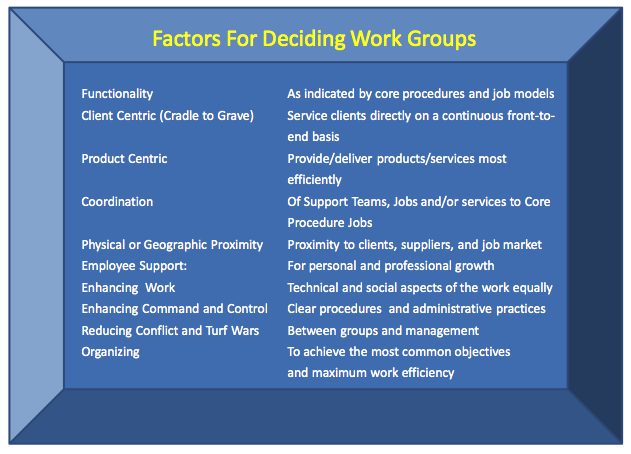

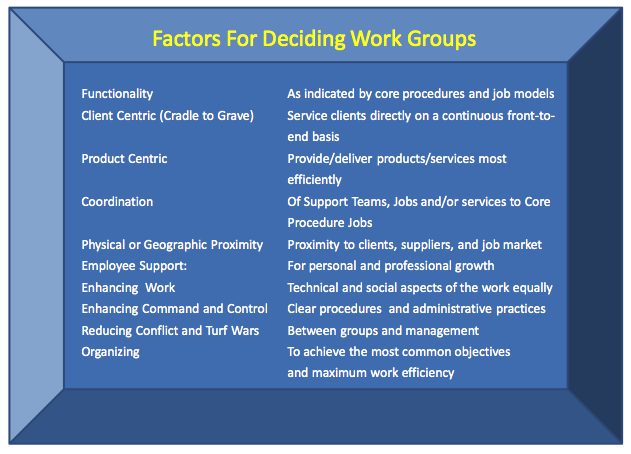

Teams are generally decided based on the flow of core processes, but not exclusive-ly. Thus, a team may be organized to complete a whole core process, across core processes or as a part of a core process. Then again, other factors may come to play as well in deciding what the teams need to be, such as following:

In AITS, IT professionals were placed in work groups based on their functionality in producing common outputs—for example, IT support services or SAP support. Jobs in these work groups interact with other work groups like engineering science services & support, or end-user support. Each of these work groups will be modeled using the same six-element work model of the Language of Work. This allows the various jobs, core processes, and the business unit models to be aligned with one another.

As is true of other work execution levels, the modeling of work groups is best done by exemplary job performers who are or will be part of the work group. They follow the order of modeling of the six work elements, as was previously for done with the business unit, core processes and jobs. Thus, each modeling output becomes the input to the next level of work execution organization.

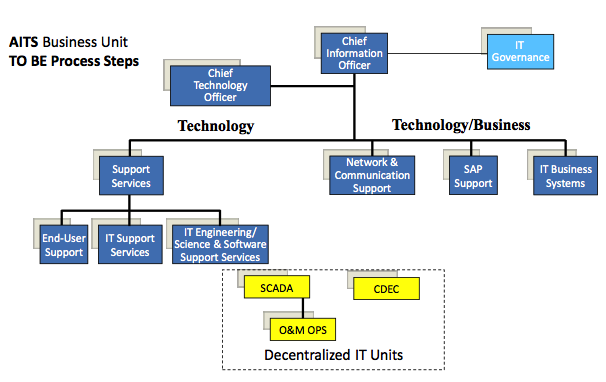

Once identified and modeled, the work groups will collectively form the basis of the second part of ORGANIZATION; what is commonly thought of as the organizational structure. This becomes the TO BE (future) process step of the business unit model.

The organizational structure, by virtue of using the Language of Work approach, practically reveals itself from the modeling that has taken place through the various work levels. This is because there is a kind of cumulative intelligence, so to speak, that the various preceding modeling reveals about how to organize the work groups. Such "Re/OrgIntel," as we might label it, is hard to describe without direct experience of the use of the Re/OrgSystem, but it invariably will clearly reveal what the organization chart—or, more accurately, the process step of the business unit—should be. Additionally, some other Re/OrgIntel is garnered by reviewing best practices.

Thus, AITS discovered through the various modeling processes that some of its major outputs were best accomplished on a decentralized basis. In so doing, they could service the whole enterprise much more efficiently in organization-wide needs, saving substantially on costs, while still allowing highly specialized IT services to be performed by technical people with other job duties.

Just a few notes about this structure: The Language of Work ModelTM makes it clear that some needed work was not being done. Specifically, the business of IT—that is, investigating new technologies and new needs, planning, budgeting and coordinating efforts was not being performed in an organized fashion. The new structure created a unit that approached IT from a business perspective. This decentralized group also served as a project management office so that new initiatives could be managed centrally after approval. In addition, it was clear that an expert in emerging technologies possessed a different skillset from a good administrator of a current IT unit. The new structure therefore demonstrated the need for a Chief Technology Officer whose job included ensuring that AITS was prepared to adopt new technologies as they became generally available.

Another need the models revealed was that of providing consulting services to various scientific and engineering offices within the agency. Until the reorganization, the centralized IT function provided little support to line departments. They therefore had created a mini-IT unit themselves, or were accustomed to using very expensive talent (usually PhDs in scientific areas) to replace paper, order and install new software and hardware or repair broken servers. In the new structure, scientists only serviced science-based technology. Technology common to all was serviced by the newly structured centralized IT department.

You see three decentralized IT units on the chart of the business unit future process steps, above. Because these three units had technology that was different from that of most other units in the enterprise, it was determined that they would keep a small IT function within their departments. The rationale was that the centralized IT department would serve units which had similar needs across the organization. Decentralized units would service others only when there was unit-specific technology in those units.

Once the new (TO BE) business unit process step has been identified, the third step of ORGANIZATION is then to identify the various management role needs, although some become apparent as the alignment of work unfolds. As with all the operational, technical and support jobs already modeled in the Re/OrgSystem, management jobs are then modeled using the same six-element Language of Work ModelTM. These management jobs are for work groups or across work groups that clearly need to be managed, and the model shows how. A manager's job will be defined to reflect how he or she should facilitate individuals and the team, as well as their interaction, as needed, with other work groups. Management job models provide a very clear way of giving meaning to how to coach, schedule, give feedback, review job performance and the like. They also provide insights into how to ensure inputs provided by other units are timely and well used—especially, how to manage what has become known as the "white space." Executives will see clearly how managers facilitate work more effectively and in alignment with the different levels of the enterprise.

In summary, from the overall description and illustration of the sample enterprise in this chapter, it should now be possible to see that the Re/OrgSystem is a highly systematic process. It organizes by modeling through and aligning succeeding work execution levels. This should clearly demonstrate the fallacy of the more common way of beginning a re/organization by designating work groups or by any of the previous means first described in Chapter 1. Such arcane methods of re/organizing give rise to much of the jockeying for position that currently undermines every organization we have consulted with. Rather than guessing what the enterprise should look like, we use a careful analysis of work elements and alignments. All work needs will be well understood and connected to meet the desired consequences of the enterprise. Work cannot be confusing, inefficient, unclear or unrelated to common ends and still provide optimal service to clients. To succeed, a business cannot have various groups at odds with one another.