Case Study: LIFE Company

Background

The LIFE Company—a real Fortune 500 company, but for whom we have given a fictitious name—provides life and disability insurance products to a wide range of consumers. The division in question, GIO, provides insurance to banks, mortgage companies and finance companies, which in turn provide consumers with long-term financing of cars, boats and homes. The idea is that the financier has a vested interest in providing the insurance product, since they would be one of the beneficiaries if the loan-taker died or was disabled. From the insurance company's side, there was a qualified list of potential clients, a built-in marketing arm, and a specific need for insurance.

For ten years, this division had languished under the leadership of an executive who paid little attention to on-going business efficiencies and customer focus. No attention was paid to costs, to speed of claims payment, to difficulties that either the customers (the banks, etc.) had in getting questions answered, or that consumers had when submitting a claim. Because the parent company LIFE is such a large organization, with annual revenues in the billions, a little division with revenues of $200 million was not particularly worthy of attention by senior management.

As long as market share was stable, and noises were few from customers, the president of this division was able to send in his annual reports, take in his annual bonus, and not spend too much time worrying about his product, his company or his obligations.

No attention was paid by LIFE until market share slipped considerably, from 7% to 3% and the executive came to retirement age. In searching for a new president for the division in question, LIFE took a risk. An investment attorney who was going through a mid-life change in interests was searching for a turn-around opportunity. Since LIFE hadn't worried very much in the past about this division, they were willing to let an unlikely guy take over. Could he improve market share? Could he reduce costs? Could he reorganize the division? Could he? He, too, wondered about all these questions, and with little experience in turnarounds, but with a lot of faith in himself and answers presenting themselves, our hero, President Andy took over the division, that we will call GIO.

Andy had thought, after 15 years as an investment attorney, that training attorneys would be a good and useful experience for him. He joined the American Society for Training and Development, read every article and book he could get a hold of, and called people who wrote books he thought he might be interested in. Although 15 months of attorney training convinced him that almost any other activity could be more fruitful, Andy had learned that performance improvement was possible through systematic means.

Industry Profile

The insurance industry is heavily dependent on clerical work; some automation has occurred, but relatively little. Credit insurance, which is what this company provides, is one kind of insurance. It is based on the model of life insurance which was developed at the turn of the century for poor working people. Over time the products, marketing and profitability of insurance has all gotten much more complex, but the same basic process holds. Products are designed, risk is assessed, prices are determined (underwriting) based on the actuarially determined likelihood of a claim being submitted, insurance products are assembled, approved by various state and federal agencies, marketed, sold, administered and claims are processed when submitted. Claims processing still depended on a hand-written claim form coming by snail mail to the claims processing office. Many pieces of paper needed to be assembled together in order to make a claims decision. This kind of insurance can be very profitable, but requires sophisticated marketing to reap its full potential.

The number and types of people required to support an insurance product include many entry level clerical types, people who "have grown up" in the business serving as supervisors; programmers and data management types, financial people who account for and invest the revenues, actuaries and underwriters, as well as marketers and managers of various functions.

Key Players

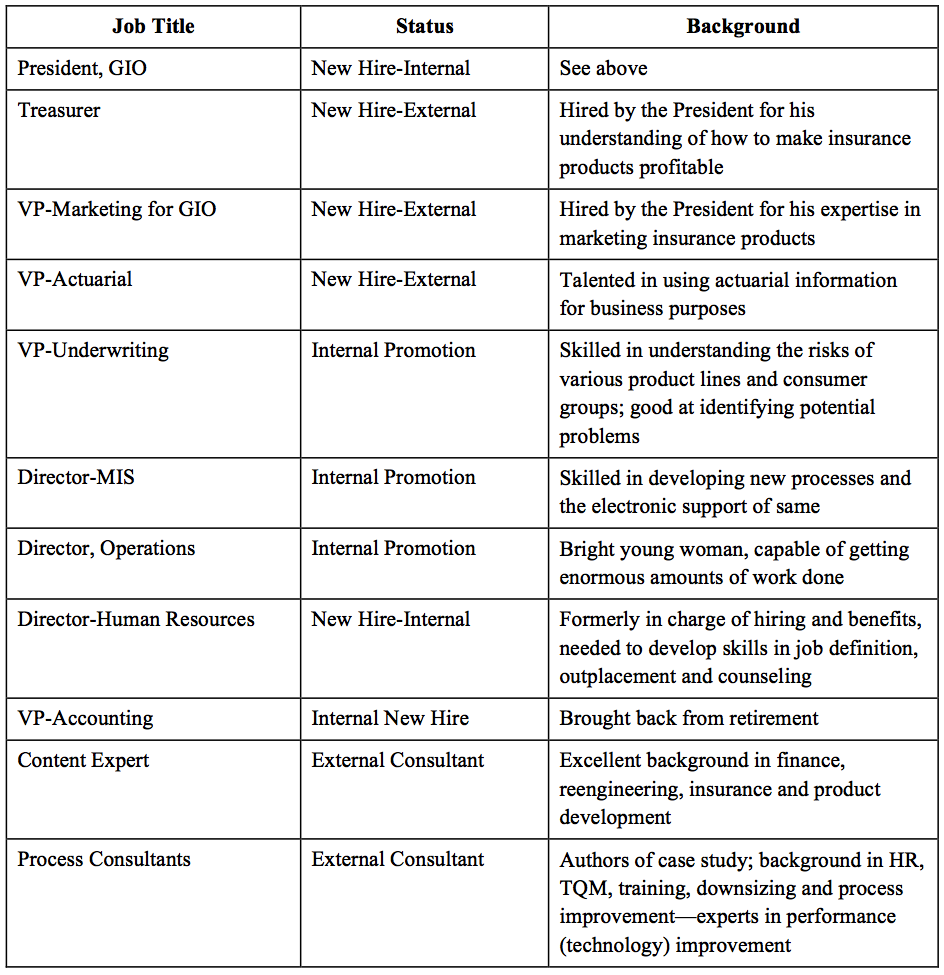

GIO has 200 employee; divided into approximately 80 jobs; 60% clerical; 10% management; 30% specialties is marketing, MIS, underwriting, claims and actuarial.

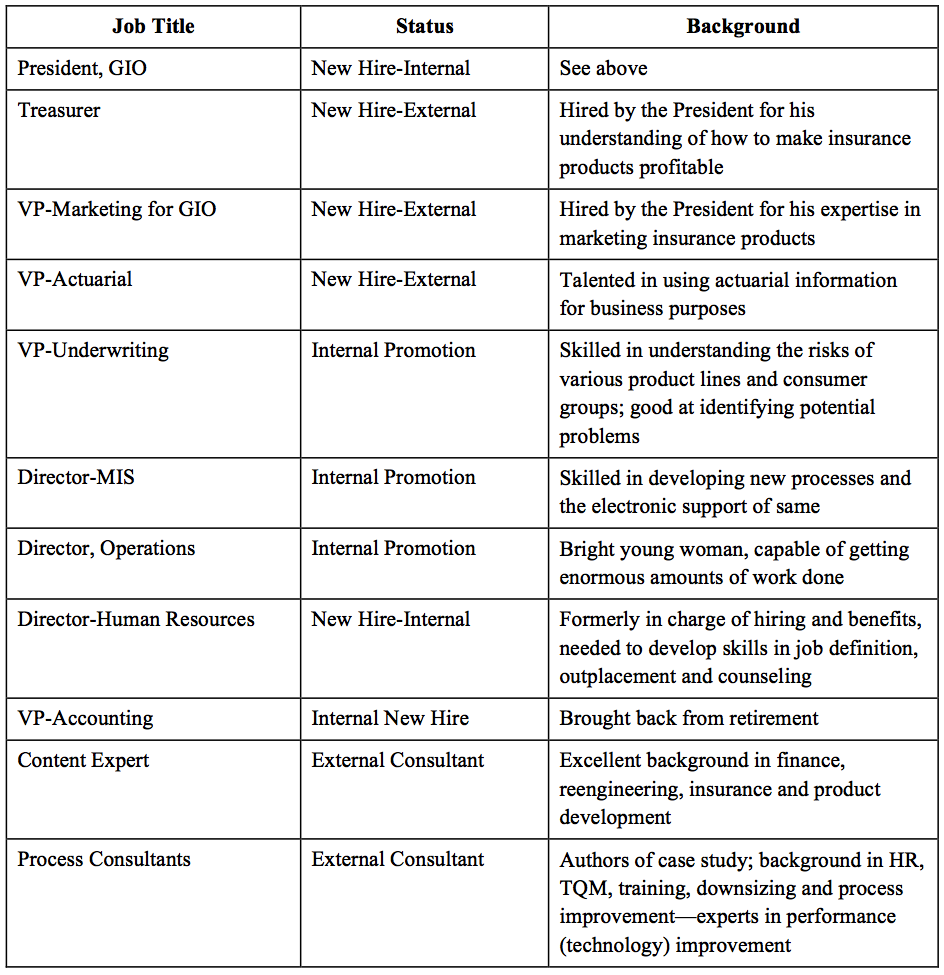

The people in the chart above were assembled in order to do the key work of turning the organization around. The directors of MIS, HR and Operations created the core team with rank and file members of the major functions; this core team was trained to define jobs, work groups, processes, and the business unit. They spent 30 working days defining all the current jobs and current processes—using the case authors Language of Work(tm) Model (see authors or HRD Press, 1995)—in the organization in order to develop a clear picture of the "AS-IS" state of the organization. This data was used to define the performance gap that needed to be filled to reach the to-be-defined "TO-BE" state. The consultants provided virtual consulting after teaching the methodology, and facilitated the marathon job modelling session.

History of Key Relationships

The newly-appointed president of GIO made it a requirement of taking the job that he be able to recruit key people for various positions. Within bounds, this was allowed. He had worked with a number of the key people labeled "new hire, external" in the table above. These people were basically "hand chosen", supportive of the president and the work he had set out to do. Although they did not know each other well at the beginning, the president was able to create a number of team-building activities, such as dinners and other events. He intuitively understood the importance of having everyone singing out of the same hymn book, typically called team building.

Although the remaining 200 employees of the company had been employed for long periods of time, some as long as 35 years, the president made it clear that unless major changes occurred in the business, the division might need to close down. While there was some denial about the future, the truth had been spoken loudly and often. Employees were urged to bid on other positions within other divisions of LIFE, to examine their retirement options, to investigate alternatives.

The GIO president reported to an executive V-P of LIFE, who in turn reported to the chairman of the company. The President of GIO was positioned to be supported in his activities, although he was expected to do the work without additional financial support from the corporate entity.

Description of the Initiative

The president needed to cut $20 million out of the cost of doing business in order to make it survive. He needed to be able to increase market share over a three-year period, but to reduce costs by 10% within one year. Since the major cost of the business was payroll, it was obvious that the way to achieve the savings would come from downsizing. But because he wanted to have a viable business at the end of the turnaround, and because he believed that the excess was caused by historically poor management, he wanted to approach the downsizing in a systematic way. At the same time, he took a pragmatic view of the budget to do the work. His position was, "If I am in the business of saving money, I need to be frugal in the money I spend to do so. My team will do the majority of the work themselves; I will hire experts who can lead us into the future, but my team will do the restructuring work."

This approach had the additional benefit of keeping all the parties well-informed about all the decisions in the project. It also afforded increased commitment to change, and many of the orientation and training processes occurred during the restructuring. Few doors were kept closed; most discussions were summarized and e-mailed to everyone so that they could keep up-to-date on the twists and turns of the project. Elevator messages were crafted in large group meetings. Thus the entire division heard the same message from everyone-the president, HR and re-structure team members. This helped to keep morale up during the re-engineering process.

Our hero and president, Andy, was not an expert in this line of business. So he knew he needed to understand what the current jobs were, and what the current processes were. With this knowledge, and with access to fine minds, free of historical biases, he was sure he could develop the new structure, the new business and make it a winner.

His pre-planning included developing a cadre of dedicated managers, committed to his vision of the future, with the skills needed to move into implementation. He went to the outside for two key resources: a woman with lots of knowledge and experience at LIFE, a background in insurance and finance, and experience in the downsizing and reengineering process. The second resource was a restructuring/reengineering team of two partners in a consulting firm known as Performance International—Danny and Kathleen Langdon. The LoWTM provided a simple framework for the team to use to address all of their issues through a common performance model that would answer and align:

• What is the current business unit?

• What is the future business unit?

• What are the current processes?

• What are the future processes?

• What are the current jobs?

• What are the future jobs?

• What is the current organizational structure (i.e. what work groups exist?)?

• What is the future organizational structure (i.e. what work groups exist?)?

Key Issues and Events

The President of GIO was the person who initiated the entire project. He understood clearly that his business changes could not be executed without a substantial HR strategy in place. He also saw that the HR strategy needed to be grounded in the principles of the Process Re-engineering. In his search for a model that would link the re-engineering and the staffing and structure in one seamless whole, he found the "Language of Work ModelTM. He did not need to begin a separate initiative, after reengineering his business, in order to get the right people in the right jobs. He did not need to go through a down-sizing that was only thinly related to the changes in the business. He did not need to keep his changes hidden from view. People could see that the new business process required fewer underwriters, fewer claims personnel, and fewer accountants. They were able to see what the needs were, compare the business' needs to their own capabilities, and if a match was not evident, they could work with the HR department to get situated in another internal or external position.

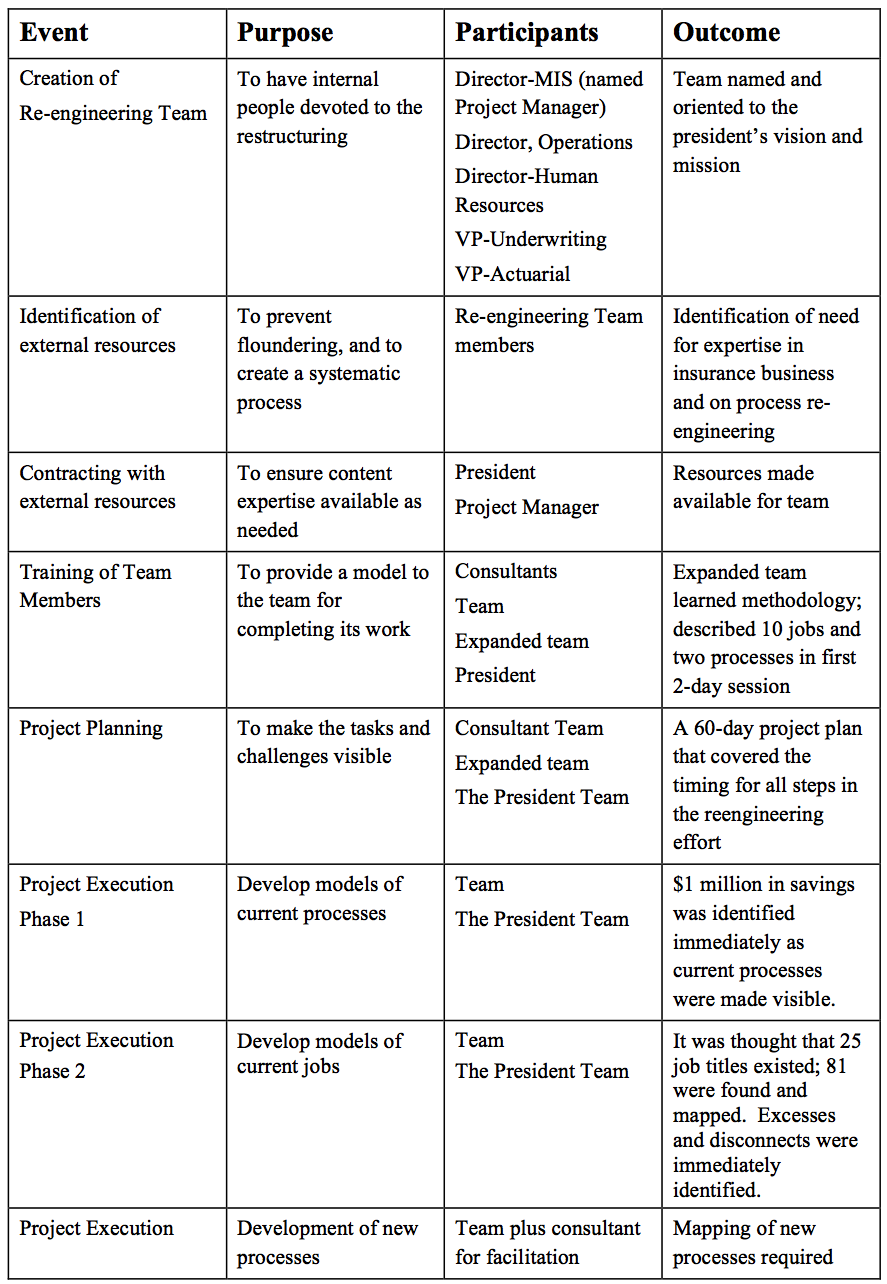

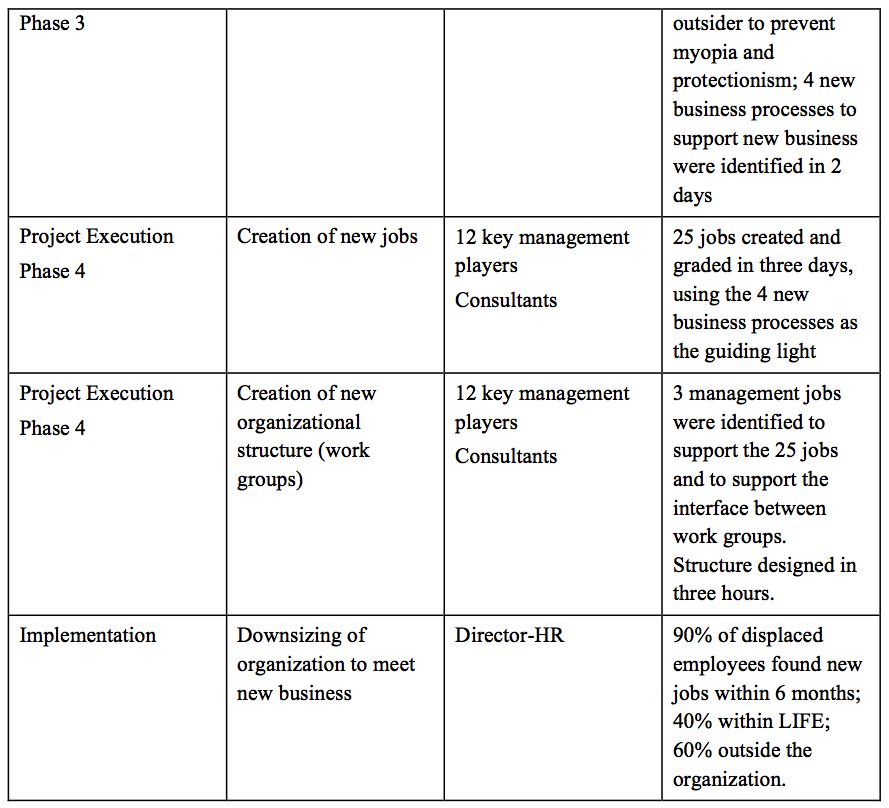

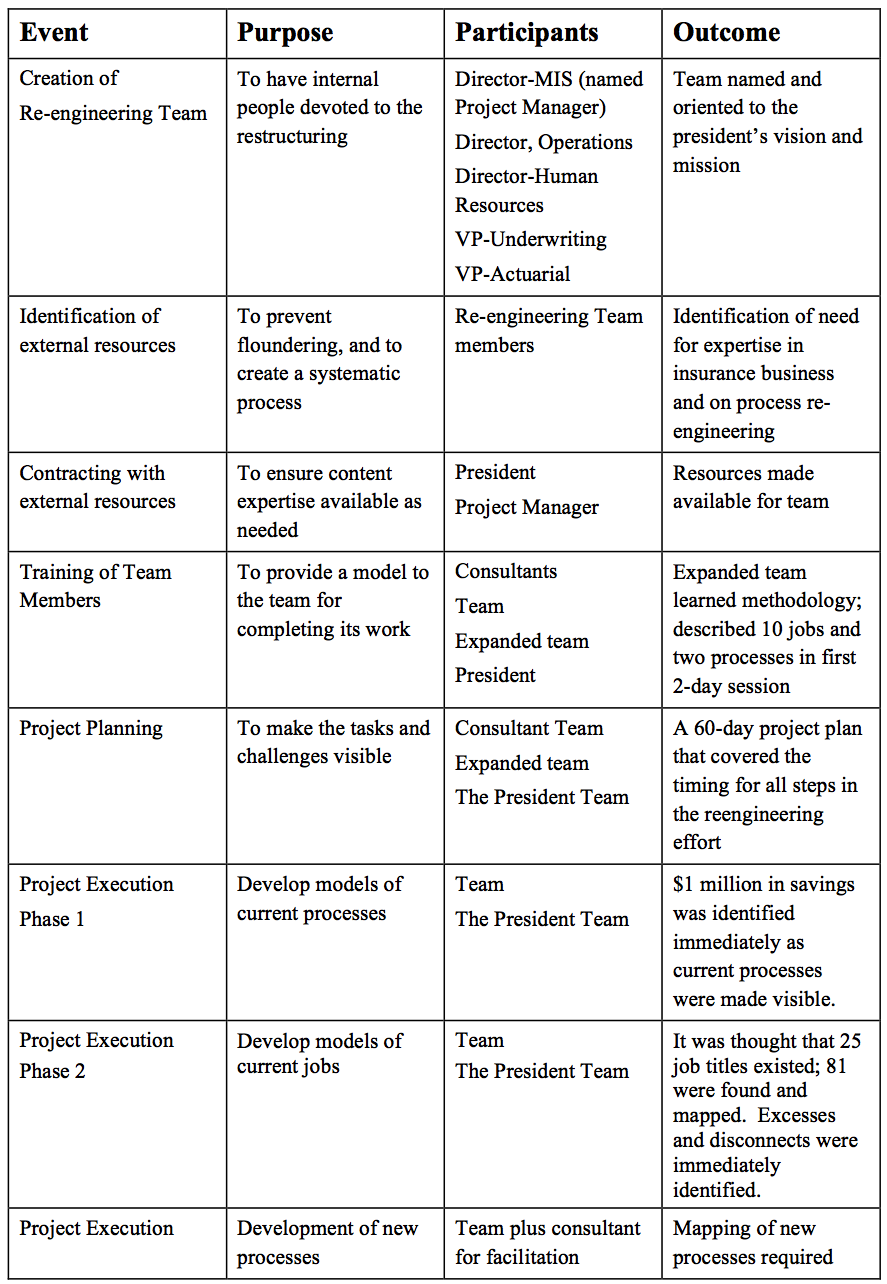

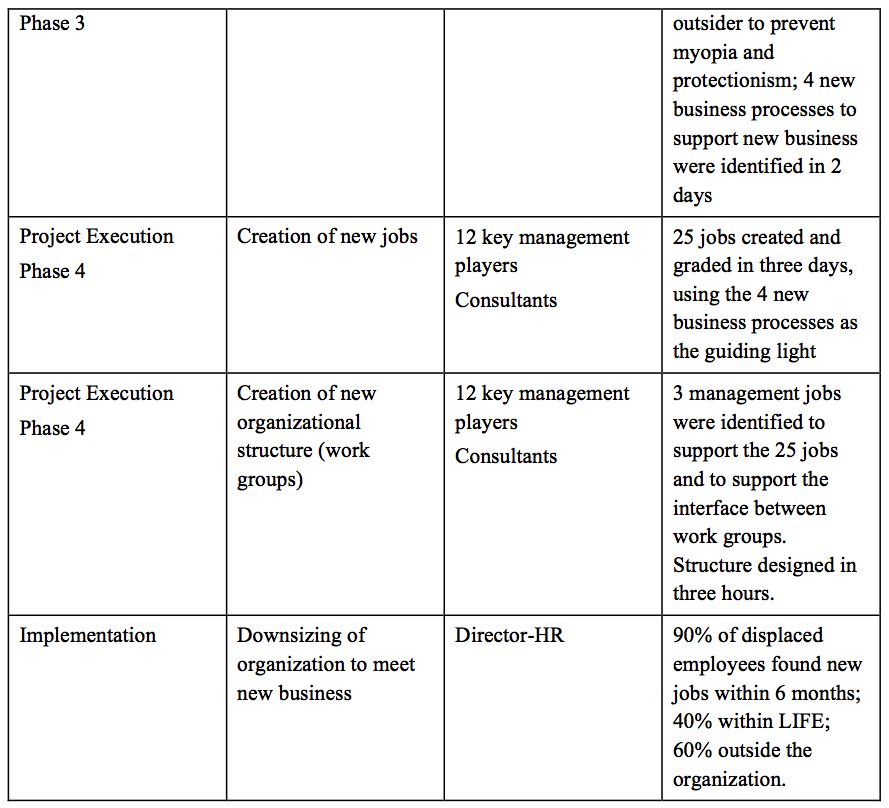

This initiative had to be completed in a 60-day time frame. Thus, the key events were:

Models and Techniques

The model used for the reengineering effort (phases 1 and 2 above) was the Language of Work(tm). The techniques included use of a 10-minute teach, a job aid for reference, master facilitation, and the distribution of copies of the New Language of Work book for reference and edification.

For the development of the new jobs and the work groups (organizational structure) the model again was he Language of Work ModelTM. The techniques included group facilitation, entry into a computer of jobs work diagrams, use of an LCD projector to project same, conflict resolution methods and simultaneous grading of the jobs by the HR department in another room at the off-site hotel that was used.

Two techniques that were used throughout the engagement was "phone-and-fax" consulting, and weekly status meetings with the president, which were dubbed the "I can't believe it meetings." The "phone-and-fax" technique meant that the Project Manager would regularly fax artifacts produced by the team. [Note: a more contemporary method includes virtual meetings and e-mailed artifacts.] As consultants we would critique the documents, identifying problems and potential problems and coach the in-house facilitator, who was also serving as the project manager. This "phone-and-fax" technique allowed the consultants to stay in very close touch with the project, while keeping costs low for the client. It allowed the project manager/facilitator to learn a number of new skills, and to depend on experts to keep out of deep trouble.

The second technique was built into the project plan. The "I can't believe it meetings" occurred every Friday afternoon. They were designed to ensure that the president did not get too involved, but also that the project could meet its tight time requirements. The Project Manager, and people he deemed necessary, met with the president weekly. Together they would review the progress to-date, identify problems, and present the issues which the team could not immediately resolve. The president was very capable of sorting out which issues were technical (i.e. demanded insurance company expertise) and which were "people" or process issues. He took on the technical issues, provided guidelines or resources to handle the people or process issues, and reinforced the team for their work. The project manager prepped for these meetings with the consultant. On the rare occasions that the president got cranky, the project manager had a wise voice for coaching on that angle as well.

Project Process Description

After all the current jobs and processes had been mapped, the new processes had to be mapped. This required some significant input from the president and the insurance content experts, as well as the new VPs of Marketing, Actuarial and Underwriting and the Treasurer. Each of these had the expertise to describe how a portion of the vision could be actualized. This part worked well; it was strategic planning at the process level and an exciting endeavor for experts.

However, when the team had made two attempts to describe the new business unit, with no success, the president approved bringing in consultants to facilitate. It was clear that the issues were too close to home, and the changes too threatening for the team to describe the new business unit without an objective, outside facilitator.

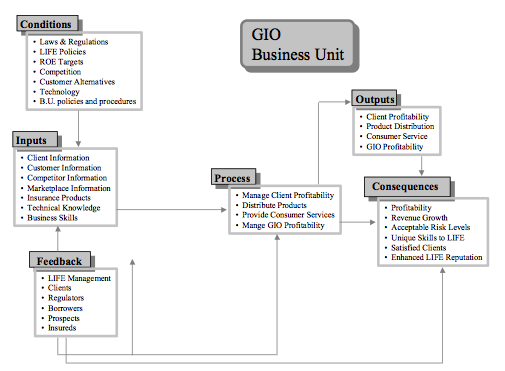

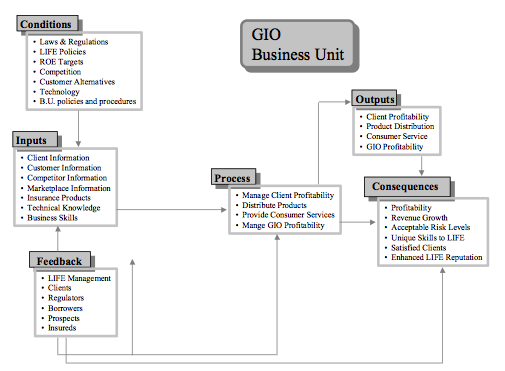

The process—the Language of Work ModelTM—used for defining the new business unit contained the following steps in a facilitated meeting. The Team was facilitated in:

• Determination of the key outputs of the new business unit (which were then compared to the outputs of the current business, making for a great number of ahas!)

• Identification of the consequences of each output, coming to understand the purpose of the business and how it contrasted with the old business

• Identification of the inputs required to produce each output of the business, creating a list of the resources needed to get into, and stay, in this new business

• Description of the key processes needed to get the outputs that would allow the business to survive. These processes were then exploded in the next level of detail.

• Articulation of the conditions under which the business is run. Because the insurance industry is highly regulated, and regulated differently in each state, the data generated here had significant impact on the creation of the products the business unit would sell

• The feedback that would tell the business unit it was doing a good job. Since the original company had limped along for 10 years without being "good" because it had no feedback mechanisms in place, this area was an important one in designing the business unit.

With the GIO Business Unit Model in place, the Team was able to design the jobs that would allow the processes to be completed and the Business Unit to meet its goals. The Team was able to finalize its Business Unit map by itself, and to revise the new processes based on the new understanding of the business unit. They were then prepared to work together with a pair of facilitators to create new jobs. These are the steps the team followed:

• Review each new process

• Identify the outputs of each process: for each output then

• Identify the possible jobs required to produce the output, often named functionally, without manager, specialist, or other tags. [Note: It is our belief that much of the understanding of the work resides in the team members. Our task is to articulate in a systematic way that thinking which team members hold. If it is counter-productive, the process holds faulty notions up to the light.]

• Identifying the output the job would produce (sub output of the process), the consequences the task would achieve, the inputs required, the process to be followed, the conditions to be attended to and the feedback to be given.

• These models were then viewed to answer the question: "Would it take one person 40 hours every week to produce this output?" If yes, then the next question was, "How many of these outputs need to be produced to meet the needs of the business?" This then answered the question of how many people were needed in various positions.

• If the answer to the first question was "no," then we found another output that a person could logically produce in a 40-hour week. This continued until there was a complete, full-time job. In a few instances, it was clear that a single output could not be combined with others; these were then defined as part-time jobs.

The job maps were posted on the walls [the facilitator has since used electronic white boards for similar projects, distributing the copies of the work product to each participant] while simultaneously being entered into a computer. Once agreement had been reached on the job description, it was handed over to two compensation specialists from Corporate Human Resources who graded each job.

At the end of three days, the team was exhausted, but 25 jobs had been described, job descriptions written and graded. Entry level skills and performance expectations were able to be inferred from the work product, allowing posting of jobs and selection to begin within days of the activity.

Results

A slide show was prepared which allowed the President of GIO to present the results of the re-engineering to LIFE's sponsoring Executive VP and the Chairman of the Board. The total number of different jobs needed to support the endeavor was reduced from 81 to 25; the total number of employees was reduced from 200 to 125. Costs went from $20 million to $12.5 million with this reduction. (Note: Although employees were not making $100,000 annually each, the cost of their pay, benefits and support in terms of equipment, real estate, supplies, software, etc. could be seen in those round numbers.) An additional $2.5 million was found in the early changes to the process. Claims costs and litigation costs were able to be cut dramatically as well, because the process was so lean that mistakes were rarely made. Particularly significant was the focus on restructuring the work groups, with the newly defined jobs, such that client needs were now to be met at a closer, more personal point of contact on a regional basis. Clients had asked for this, and now would receive it in fact.

Conclusions and Recommendations

Much of the success of the project lay in the hands of the president, who was our client. He saw his role, not as the conductor, but as one of the players in a jazz quintet. Unlike an orchestra conductor who is trying to make the notes on paper sound beautiful and as planned, his task was to make beautiful music. The exact outcome was not always clear, but with good talent and communication, something gorgeous could be produced. His selection of a model on which to frame discussion and outcomes, while reducing emotional ties, and consultants who were compatible with him was a critical step in the success of the project.

The participants in this project, the Team, experienced growth on many levels. Rarely had they worked so hard, producing so much in such a short period of time. Because literally everyone was involved, the approach also allowed for much of the orientation and learning of the new process and structure to occur during definition, as compared to most restructuring were the outcomes are imposed on those affected. Because of the conscientiousness of the President, they were comfortable that people would be treated with human dignity in the entire process. This allowed them to make decisions and recommendations for new jobs that were very much in keeping with individual's needs. The players have all gone on to new jobs, many in new organizations that suited their personal and professional goals more closely. Several are using the model in their current settings.