A REVOLUTIONARY IDEA

Look for opportunity more than security and stability.

Consider the breadth of an opportunity and do your best.

—Roy H. Park

After formal research and several weeks of old-fashioned

brainstorming by Ag Research employees testing as many as 500 names, nothing

seemed to stand out with the universal recognition they were looking for. As a

last resort, Bob Flannery suggested maybe they should “bring in Duncan Hines.”

A lightning bolt struck, and my father instinctively knew that was the name

that would work.

Pops decided that he might as well aim high. The man to go

to was Duncan Hines. As the best-known food, restaurant, and lodging expert in

the country in the late 1940s, his name was, in the minds of most Americans,

synonymous with good food. The Bowling Green Jr. Women’s Club said he was

better known across America than the United States Vice President Alben

Barkley, even in Kentucky, the home state of both.

Travelers didn’t venture far from home without Hines’ book

of roadside restaurant reviews called Adventures in Good Eating, as well as

guidebooks on lodging, resorts and cooking. Hines had helped millions of hungry

Americans find good food, even in the least likely locations. My father was

determined to get that name, and its seal of approval, on his products. Hines

had, of course, been approached time and time again by people promising to make

this self-made man far richer than he ever dreamed, and time and time again he

rejected their offers.

After all, he had a national reputation and was doing just

fine on his own bottom line.

Born in Bowling Green, Kentucky, on March 26, 1880, Hines

was the youngest of six siblings. His mother died when Duncan was four, and he

and his youngest brother spent their summers at their grandparents’ farm in the

country. His grandmother was a wonderful cook who made full use of the farm’s

bounty of fresh and wholesome food: candied yams, sausage, country ham, turnip

greens with fatback, beaten biscuits, cornbread, and pecan pie. Hines recalled

that it was not “until after I came to live with Grandma Jane did I realize

just how wonderful good cookery could be.”

Duncan left home in 1898 to work as a clerk for Wells Fargo

clerk in Albuquerque, New Mexico, and a year later was assigned to their

Cheyenne, WY, office, where he met Florence Chattin, his bride-to-be. His

courtship was complicated by her family’s opposition to their marriage for the

next four years because his job level and bankroll did not make him a worthwhile

suitor for their daughter’s hand.

In 1902, he changed jobs, ending up in Mexico with a mining

company, and worked hard to make money, establish a nest egg, and embellish his

image. During his travels, with a palate accustomed to good food, he continued

to find it a challenge to locate eateries good enough to accommodate his

discriminating taste. Then, after her father passed away, Florence moved to New

Rochelle, NY, and Duncan left the mining life to join her. They were married

there in September 1905, and shortly after, he and his new bride moved to

Chicago, where he worked for thirty-three years for the J.T.H. Mitchell company

as a traveling salesman designing, writing, and producing corporate brochures.

As Pops told it, “Duncan was a specialty advertising and

printing company salesman from Bowling Green, KY, who was also a freelance

promotion man. He would go out and find a large company where—as he put it—the

‘smoke was coming out of smokestack’—and he’d talk to the president about

writing a book or a brochure.” My father smiled at the recollection, “Most of

the time they bought it.”

Of all his accomplishments, Hines took the most pride in a

book he did for Brink’s Express. The manager he saw there said that most

journalism was very poorly done, and that if Hines could produce a book without

one typographical or grammatical error, he could set his price. But if there

was only one error, he would be paid nothing. Hines accepted the challenge and

pulled it off. He told my father that there was actually one error in the book,

but they never found it at Brink’s.

In the course of his work, Hines traveled a great deal,

often taking Florence with him, and together they began to “collect” the names

of restaurants and hotel dining rooms that consistently served excellent food.

He would return home with fond memories of a certain deep-dish apple pie or the

recollection of the taste and texture of a particular batch of buttermilk

biscuits.

Hines’s restaurant “collection” became a passion. People

began to drop him notes about other good eating places, and he would advise his

customers and good friends where to eat. In 1935, instead of a conventional

Christmas card, the fifty-five-year-old Hines sent out a small brochure listing

167 superior eateries in thirty states and Washington, DC. He headed it

“Adventures in Good Eating,” and the response was overwhelming. Friends

requested additional copies, as did strangers who had seen the list. Public

relations was Hines’ profession, eating merely his hobby, but in 1936, he

realized that he could turn his hobby into a business and began publishing the

book Adventures in Good Eating. The first edition was not an overnight success,

selling 5,000 copies and netting a $1,500 loss. But by 1938, an article in the

Saturday Evening Post and word-of-mouth put Hines firmly in the black, and he

left sales and moved back to Bowling Green to review restaurants full-time,

traveling up to 50,000 miles a year.

Hines’ strategy of simply letting the public know where they

might find quality food, carefully prepared by a competent chef in clean

surroundings, answered a real need. In his many years on the road, he had

visited his share of bad restaurants. Of one, Hines wrote, the gravy resembled

“library paste.” Another offered meals “as tasty as seasoned sawdust.”

Cleanliness was a problem, too. As he said about one greasy spoon, “If you get

anything after the cockroaches are finished, you’re lucky.” Diner beware, Hines

warned: “Usually the difference between the low-priced meal and the one that

costs more is the amount you pay the doctor or the undertaker.” Poor

restaurants offended him personally, and he said he often expressed a wish to

“padlock two-thirds of the places that call themselves cafes.”

Fine restaurants were another story, and the places he liked

best received enthusiastic, joyful write-ups. According to Hines, one

Massachusetts institution made “a fellow wish he had hollow legs.” One of his

trademarks was to mention each restaurant’s specialties.

A 1941 listing for a restaurant in Tampa, FL, read: One of

the most popular eating places in the South, four dining rooms, famous for its

Spanish and French dishes. Marvelous sea food, especially their grilled Red

Snapper steaks. Try their stuffed pompano, or crawfish, “Siboney style” or stone

crabs, “Habanera” when in season. And to top all, have some “Espanol” or

cocoanut cream dessert. Prices consistent with excellent quality.

Another in Central New York: Watkins Glen State Park in the

heart of the Finger Lakes region is said by many to be the Grand Canyon of the

East. While here, you may put up at The Homestead, where “mother does the

cooking.” Chicken, steak or lake trout dinners their speciality. B., 35c up;

L., 50c up; D., 50c to $1.

Newsweek magazine called him a “full-time eater-publisher,”

and the Saturday Evening Post called him “the country’s champion diner-out.”

With a second edition of critiques in mind, Hines sometimes

grazed through six or seven restaurants a day and relied on a network of

trusted volunteers to keep him up to date on those he couldn’t reach. Their

ranks included corporate chefs, bank and university presidents, and well-known

personalities from cartoonist Gluyas Williams and travel lecturer Burton Holmes

to radio commentator Mary Margaret McBride and Lawrence Tibbett, the opera

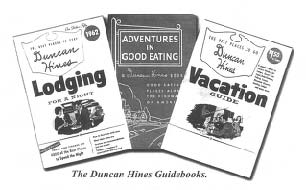

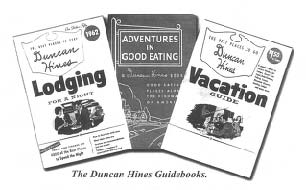

singer. He was doing what Tim and Nina Zagat reinvented nearly fifty years

later. Meanwhile, he branched out, publish

ing in 1938 the Lodging for a Night motel and hotel

guidebook to help travelers find the best places to stay. “What do I care if

Washington slept here?” Hines demanded, describing his reviewing philosophy.

“Do they have a nice, clean bathroom and do the beds have box springs? That’s

what I want to know.”

The same enthusiastic listing he used for the restaurants

applied to lodging he liked. For example, a 1962 description for a motor hotel

in Charlotte, NC, read: 156 rms. A.C., Ph., TV. Baby cribs, baby sitters.

Sundeck, heated S.P., wading pool. Free ice. D.R., C.L. An outstanding new

establishment. Airy units with dressing areas, some with studio arrangements,

and a unique bubble enclosed pool for year-round swimming. Fine dining

facilities. SWB $9-$12. 2WB $12-$15. Suites avail. No pets. Res. advis. Tel. ED

2-3121.

So the former traveling seller of advertising specialty items,

brochures, and business pamphlets, in an era long before such establishments as

McDonald’s and Holiday Inn guaranteed uniform standards, became the source

advising thousands of travelers on where to eat and sleep while on the road. By

the end of 1939, his books sold 100,000 copies a year. Claiming there was

“hardly a hamlet or crossroad” in the U.S. he had not visited, he also traveled

to Canada, Mexico, and Hawaii and seven countries in Europe. Between his two

books, more than 7,000 “recommendations” were listed. I should point out here

that all of these listings were free. Other guidebooks were financed by the

very establishments they purported to review, but Hines consistently refused

all offers of advertising.

In 1939, Hines first published a book of his favorite

recipes, Adventures in Good Cooking, and he had become virtually an

institution, unique in the country. Perhaps no one, until the advent of Julia

Child, had a comparable influence on American cuisine.

By the time he was sixty-eight, he was internationally

renowned for his ratings on eating places around the world and sales of his

three guidebooks, including the Duncan Hines Vacation Guide published in 1948,

rose to half million a year.

So here was my thirty-nine-year-old father with a lineup of

food producers looking for a brand name after Duncan Hines, at age sixty-eight,

had already become a household name. But as Leo Burnett, whose advertising

agency handled Procter & Gamble products, and whom my father was later to

meet and work with, said, “When you reach for the stars, you may not quite get

one. But you won’t come up with a handful of mud, either.”

The challenge Pops faced, he said, “was how to tie the bell

to the cat. I sent my people to the Cornell library and had them research

everything they could find on Hines. Before I met him, I knew more about him

than he did about himself, including his passion for watches.”

Of course, Hines had no idea who Roy Park was, so he had no

intention of granting him an audience. But the two self-starters who had come

off a farm had a lot more in common than either one of them thought. After

months of trying to get through the door, and thanks to his exhaustive research

on the life and achievements of Duncan Hines, my father prevailed upon a

prominent restaurant owner he knew in Raleigh to call a friend of Hines who was

a restaurant owner in Virginia to arrange a meeting with him.