CHAPTER 7: REVERSE JUDGMENT—MY FIRST

TWENTY-ONE YEARS

There are few successful adults who were not first

successful children.

—Alexander Chase

As a student at UNC, I wrote about my path to adulthood

being the result of the way I was raised and of the way I responded to my

parents during my first twenty-one years.

When I was about six we still lived in an apartment

building. I had a couple of friends and without a real lawn or woods to

explore, collecting bugs around the building and parking lot was one of our

pastimes. With tin cans clutched in our fists we searched the grounds for

anything we could catch. I always wanted to use a glass jar to be able to see

what we caught, since watching praying mantises and lightning bugs in a tin can

just didn’t cut it. But my mother warned that a jar could break and cut me. The

first day I snuck one out I fell and broke the jar, nearly losing the tip of a

finger on my right hand. I ran back to the apartment, blood making a trail up

the sidewalk, stairs, and hallway into the apartment. I was not quiet about the

pain, and my mother piled me into the car and headed for the doctor. On the way

she made sure to remind me of her earlier warnings, and of course later called

my father at his office.

It was one of those, “wait until your father gets home”

moments, and I expected to be punished. But when Pops came home, he just asked

if it hurt, and that was it. They both told me that I would know better next

time, and I agreed I sure would. The scar is still there to remind me, and I

see it every day.

As Will Rogers said, if good judgment comes from experience,

then a lot of that comes from bad judgment. Incidents like this proved my

parents knew what they were talking about. They would warn me not to do

something, I would go ahead and do it and suffer any consequences. Punishment

came only when the consequences of my error didn’t come naturally. That didn’t

happen often because life had plenty of punishment in store for me whenever I

tempted it. So at an early age, I developed an inner discipline, and instead of

resenting their guidance, I mostly appreciated my parents’ advice.

When I was a little older, we moved into a house and I

developed a new group of friends. The antics of our small gang were mostly

harmless, but when some of them tried their hand at stealing, I wanted no part

of it. The few who stole usually got caught, and when I stop to think about it,

I remember one of them spent a stretch in reform school.

I had no brother, but my closest friend growing up took the

place of one. He was an only child and his home wasn’t a happy one. He spent

most of his time at our house. He told me his parents would argue a lot and had

a way of catching him in the middle. I tried to help him through the tough

spots. One year his mother didn’t give him a birthday party. I told my mother

about it and we had a party for him at our house the next day. My parents were

always willing to help somebody out who needed it, and it rubbed off on me.

My friend went away to preparatory school when I did, but he

flunked out. He went to another and flunked out of that, too. He was an

outstanding artist and at a young age fled to New York and was famous for a

while in the art community. Then he got involved with drugs and flunked out of

life as well. Seeing things like this helped keep me straight early on. As I

said, Pops traveled a lot in his work, and sometimes we would all go with him.

Before I was fifteen, I’d been in every state in the country except four and in

a few countries outside.

These family trips were fun and brought us together despite

the fact that Pops always worked hard. His work came first, and that left no

time to play. He apologized to me for not being more of a companion when I was

young. He explained he had to get his work done so that he could do things for

us. I didn’t like it, but that was the way it was. But his hard work did set an

example for me.

During this time, Dottie became more than just a mother. She

was a friend and companion. Often we would travel together and meet Pops at the

other end. She put herself out, and when we were too young to drive, she did

more than her share of taking groups of us to movies and parties and retrieving

us afterward.

There’s no question that when my parents laid down rules

sometimes I broke them. But they said the rules were because they loved me.

“Someday you’ll have a boy of your own, Son, and you’ll feel the same way,”

Pops would say. “You may not like this now, but wait a few years and you’ll see

what I mean. When we ask you to do this, or tell you not to do that, we’re

doing it for your own good, and not to hurt you. And maybe we’re a little

selfish about it now, and you probably think we are, but we don’t want anything

to happen to you.”

I didn’t want anything to happen to my younger sister,

either, and as she was growing up she went through the same stages I had. I

felt I helped to raise her right along with my parents. I could get through to

her and she would listen to me. As an older brother, I gave her the benefit of

what experience I had and began to experience what my parents meant about

having children of my own.

When I was about thirteen, I remember my parents had a

fight.

My father was at a crisis point in his business. Because he

worked constantly, my mother threatened to leave him. I wasn’t going to stand

by, so I played the role of mediator. I told them I loved them both and didn’t

intend to spend the rest of my life visiting one and then the other. Something

that foolish just wasn’t going to happen to our family. My sister backed me up

on everything I said.

We all ended up in the living room talking it out, and when

I could tell things were getting better, I quietly exited with my sister. After

a while we could hear them laughing, and they came out and thanked us for being

great kids. We all went out to dinner together that night.

Except for incidents like this, we shared a sense of humor

and knew how to make each other laugh. Problems were settled through

discussion. I can’t remember a disagreement we had that didn’t end in apologies

and a better understanding of each other. We could always tell when one of us

was bothered by something, and we’d bring it out and resolve it then and there.

Coming from a large North Carolina farm family, my father

did what he had to do on his own—putting himself through college, becoming the

student editor, and winning every honorary key on campus. Dottie was proud of a

charm bracelet made from them. I respected Pops’s opinion, but more

importantly, I felt he respected mine. Enough to back down if he saw I was on

the right track. He would refer to his wealth of experience, apply it to me,

and I would sometimes get angry and say, “Times have changed, Pops.” He would

tell me that times really hadn’t changed, that basic things were always basic,

and that I would eventually find out what he meant.

(And I did. I came to understand that children only begin to

realize the value of their parent’s advice when they have kids of their own.

Unfortunately, then it’s too late for a grandparent to give advice on how to

raise them.)

When I was twelve, my mother began to let me join them

drinking wine at supper. Whenever they ordered a bottle of Champagne when we

ate out, I’d have a glass, too. When I reached sixteen, they began to let me

drink Scotch. That way I began to accept alcohol in a natural way, and as I

grew older, with some notable exceptions, I didn’t think it was all that smart

to drink to excess.

The same principle applied to smoking. When I began to think

it was smart to smoke, Pops saw it coming, and gave me a cigar one day. It

cured me for a while, but unfortunately, I picked up smoking again. It started

my first year at Cornell when the going got rough and I was under pressure.

Dottie didn’t like it, but Pops didn’t say anything. He told me that it wasn’t

a good habit to start, but I’d have to decide on my own. When things got

better, I quit for a while, and then I took it up again. But that was my

decision, too.

My father set an example for me to live up to but left the

choices and decisions up to me. If I knew I was right, he would back me up.

Sometimes, if he tried to push me into some things against my will, my mother

would intervene. As I grew older, I became more and more independent. They let

me choose my friends, my education, and my career. They loved me as a son, but

I think they respected me as a person. Mutual respect was a great force behind

my development.

Pops wasn’t blind to my faults, and he pointed them out in a

gentle way. And I appreciated this. We were close and would talk freely about

everything. I never held anything back, and my parents didn’t either. They were

reasonably open discussing sex with me at an early age. I learned about it on

my own, but they confirmed my discoveries without embarrassment when I brought

them up. Out in the open, sex became a natural part of life, put in its proper

place. I noticed the guys who boasted the most about their conquests always had

the most complexes.

Pops admitted that he was pretty active in this area when he

was young, and the one thing he warned me about was getting involved in a

parental suit, or what he called a “shotgun wedding.” Dottie and Pops even made

a bet when I was sixteen. They bet I’d lose my virginity before I was eighteen.

I won’t tell you who won, or whether I already had, but it shows their attitude

about the subject.

My grandmother was religious, and when I was young, I’d

often ask her questions about the Bible. She had a clear sense of right and

wrong. She helped me believe in a being greater than us poor humans before I

ever went to church, and I developed a religious outlook on life at an early

age. Pop was a God-fearing Baptist before he became a God-fearing Presbyterian,

but for a long period he never had time to go to church. He’d work all day

Sunday from morning to late at night. My mother wanted to go but didn’t go

without him. I didn’t feel the need since my grandmother said I could reach Him

from wherever I was. So though we kept God close, we didn’t always go to church

to stay in touch. When my father had more free time, he made up for it by

becoming an elder in Ithaca’s First Presbyterian Church.

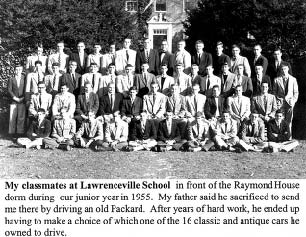

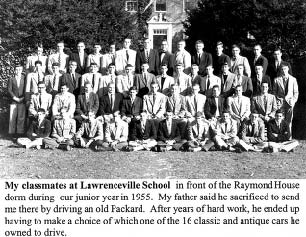

My mother and father made sacrifices for us along the way,

some that I never knew about. When they sent me away to the Lawrenceville

School, they bought this old Packard. Pops had explained he got it as a

collector’s item, and they drove it for three years. When he sold it my first

year of college, I asked him why. He said he was going to get a better car and

that was all.

He later said in one of our talks that they had driven the

car because it was all they could afford and put me through an ex

pensive prep school at the same time. Pops said he had my

college education paid for through an insurance policy even before I was born.

I point all this out because an old farmer’s advice is to

live a good, honorable life so when you get older you can think back and enjoy

it a second time. Judgment doesn’t wait at the end of the line. In our

generation, in these days and times, every day is judgment day.

Overall, I had good parents, and their parenting allowed me

to emerge from childhood with plenty of hope for the future. My father’s letter

to me on my twenty-first birthday had spelled out the principles he (mostly)

lived by, and his attitude toward me.

But things were later to change when I entered his business

world.

(Back to Contents)